Mutual Epistemic Dependence and the Demographic Divine Hiddenness Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE (Last Revised 10/19/2017)

CURRICULUM VITAE (Last Revised 10/19/2017) KEITH McKENDREE PARSONS POSITION: Professor of Philosophy University of Houston-Clear Lake Dates of Employment: September 1, 1996 to present. Assistant Professor, 9/96-9/2002 Associate Professor, 9/2002-9/2006 Promoted to Professor, 9/2006 ADDRESS: Box #296 University of Houston-Clear Lake 2700 Bay Area Boulevard Houston, TX 77058 Office Phone: (281) 283-3361 Home Phone: (281) 309-1944 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: Ph.D.--History and Philosophy of Science, The University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; 1996 Dissertation: Wrongheaded Science? Rationality, Constructivism, and Dinosaurs; Supervisor: James Lennox Ph.D.--Philosophy, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada; 1986 Dissertation: Science, Confirmation, and the Theistic Hypothesis; Supervisor: C.G. Prado; M.A.--Philosophy, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA; 1982 Thesis: Miracles and Christian Apologetics; Supervisor: James Humber Master of Theological Studies--Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; 1981; awarded cum laude B.A.--Religion and Philosophy, Berry College, Rome, Georgia; 1974; awarded magna cum laude AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION: Philosophy of Science; History of Science and Technology; Philosophy of Religion AREAS OF COMPETENCE: Darwinism; History of Philosophy; Logic; Critical Thinking PUBLICATIONS: Books: Polarized: Confronting the Collapse of Truth, Civility, and Community in Divided Times, Co-authored with Paris N. Donehoo, D. Min. Prometheus Books, (forthcoming, 2018). Bombing The Marshall Islands: A Cold War Tragedy. Co- authored with Robert Zaballa, Ph.D. Cambridge University Press (2017). It Started with Copernicus; extensively revised and expanded (three new chapters) edition of Copernican Questions, Prometheus Books (2014). Selected by Choice Reviews as an Outstanding Academic Title in 2015. -

The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: a Version of the Argument from Reason

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-04-30 The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason Hawkes, Gordon Hawkes, G. (2019). The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/110301 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Argument from Logical Principles Against Materialism: A Version of the Argument from Reason by Gordon Hawkes A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN PHILOSOPHY CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2019 © Gordon Hawkes 2019 i Abstract The argument from reason is the name given to a family of arguments against naturalism, materialism, or determinism, and often for theism or dualism. One version of the argument from reason is what Victor Reppert calls “the argument from the psychological relevance of logical laws,” or what I call “the argument from logical principles.” This argument has received little attention in the literature, despite being advanced by Victor Reppert, Karl Popper, and Thomas Nagel. -

Ordinary Morality Implies Atheism

ORDINARY MORALITY IMPLIES ATHEISM STEPHEN MAITZEN Acadia University Abstract. I present a “moral argument” for the non-existence of God. Theism, I argue, can’t accommodate an ordinary and fundamental moral obligation acknowledged by many people, including many theists. My argument turns on a principle that a number of philosophers already accept as a constraint on God’s treatment of human beings. I defend the principle against objections from those inclined to reject it. In his Elements of Moral Philosophy, James Rachels remarks that “it isn’t unusual for priests and ministers to be treated as moral experts.... Why [he asks] are clergymen regarded in this way? ... In popular thinking, morality and religion are inseparable: People commonly believe that morality can be understood only in the context of [theistic] religion.”1 This popular association of morality with theism may explain why atheists showed up as the single most distrusted minority group in a recent opinion survey conducted in the United States, much to the surprise of those who conducted the survey.2 Despite that popular association, I’ll argue that theism and ordinary morality are incompatible: theism can’t accommodate an ordinary and fundamental moral obligation acknowledged by many people, including many theists. My argument turns on a principle that a number of philosophers already accept as a constraint on any plausible theodicy. I’ll defend the principle against objections from those inclined 1 James Rachels, Elements of Moral Philosophy (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 3d. ed., 1999), 53–54. Although Rachels gives the title “Does Morality Depend on Religion?” to the relevant chapter of his book, he restricts his discussion of religion to (Christian) theism: “In discussing the connection (or lack of connection) between morality and religion, I will focus on one religion in particular, Christianity” (55). -

Atheism and Analogy: Aquinas Against the Atheists Dan Linford Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Instit

Atheism and Analogy: Aquinas Against the Atheists Dan Linford Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Philosophy Joseph C. Pitt Benjamin Jantzen Matthew Goodrum April 25, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: atheism, theology, analogy, God, Berkeley, Hume, Anthony Collins, d'Holbach Atheism and Analogy: Aquinas Against the Atheists Dan Linford ABSTRACT In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas developed two models for how humans may speak of God – either by the analogy of proportion or by the analogy of proportionality. Aquinas's doctrines initiated a theological debate concerning analogy that spanned several centuries. In the 18th century, there appeared two closely related arguments for atheism which both utilized analogy for their own purposes. In this thesis, I show that one argument, articulated by the French materialist Paul-Henri Thiry Baron d'Holbach, is successful in showing that God-talk, as conceived of using the analogy of proportion, is unintelligible non-sense. In addition, I show that another argument, articulated by Anthony Collins (Vindication of Divine Attributes), George Berkeley (chapter IV of Alciphron), and David Hume (chapter XII of Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion) can be restructured into an argument for the position that the analogy of proportionality makes the distinction between atheism and theism merely verbal. Since both of these are undesirable consequences for the theist, I conclude that Aquinas's doctrine of analogy does not withstand the assault of 18th century atheists. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Aaron Yarmel,1 Walter Ott,2 Ted Parent,3 Roger Ariew,4 and Dan Fincke5 for discussions that helped to complete this thesis. -

Ignosticism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit Search Ignosticism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Ignosticism, or igtheism, is the theological position that every other theological position Main page Part of a series on Contents (including agnosticism) assumes too much about the concept of God and many other Irreligion Featured content theological concepts. The word "ignosticism" was coined by Sherwin Wine, a rabbi and a Current events founding figure in Humanistic Judaism. Random article It can be defined as encompassing two related views about the existence of God: Donate to Wikipedia 1. The view that a coherent definition of God must be presented before the question of the Interaction existence of god can be meaningfully discussed. Furthermore, if that definition is Irreligion unfalsifiable, the ignostic takes the theological noncognitivist position that the question of Secular Humanism · Post-theism Help Freethought · Secularism About Wikipedia the existence of God (per that definition) is meaningless. In this case, the concept of Secularity · Criticism of religion Community portal God is not considered meaningless; the term "God" is considered meaningless. Anti-clericalism · Antireligion Recent changes 2. The second view is synonymous with theological noncognitivism, and skips the step of Parody religion Contact Wikipedia first asking "What is meant by 'God'?" before proclaiming the original question "Does Atheism God exist?" as meaningless. Demographics · History Toolbox Some philosophers have seen ignosticism as a variation of agnosticism or atheism,[1] while State · Militant · New Print/export Implicit and explicit others have considered it to be distinct. An ignostic maintains that they cannot even say Negative and positive Languages whether he/she is a theist or an atheist until a sufficient definition of theism is put forth. -

A Study on Religion

A Study on Religion Religious studies is the academic field of multi-disciplinary, secular study of religious beliefs, behaviors, and institutions. It describes, compares, interprets, and explains religion, emphasizing systematic, historically based, and cross-cultural perspectives. While theology attempts to understand the nature of transcendent or supernatural forces (such as deities), religious studies tries to study religious behavior and belief from outside any particular religious viewpoint. Religious studies draws upon multiple disciplines and their methodologies including anthropology, sociology, psychology, philosophy, and history of religion. Religious studies originated in the nineteenth century, when scholarly and historical analysis of the Bible had flourished, and Hindu and Buddhist texts were first being translated into European languages. Early influential scholars included Friedrich Max Müller, in England, and Cornelius P. Tiele, in the Netherlands. Today religious studies is practiced by scholars worldwide. In its early years, it was known as Comparative Religion or the Science of Religion and, in the USA, there are those who today also know the field as the History of religion (associated with methodological traditions traced to the University of Chicago in general, and in particular Mircea Eliade, from the late 1950s through to the late 1980s). The field is known as Religionswissenschaft in Germany and Sciences de la religion in the French-speaking world. The term "religion" originated from the Latin noun "religio", that was nominalized from one of three verbs: "relegere" (to turn to constantly/observe conscientiously); "religare" (to bind oneself [back]); and "reeligare" (to choose again).[1] Because of these three different meanings, an etymological analysis alone does not resolve the ambiguity of defining religion, since each verb points to a different understanding of what religion is.[2] During the Medieval Period, the term "religious" was used as a noun to describe someone who had joined a monastic order (a "religious"). -

ABSTRACT the Argument from Divine Hiddenness: an Assessment Ross Parker, Ph.D. Mentor: Trent Dougherty, Ph.D. the Argument From

ABSTRACT The Argument from Divine Hiddenness: An Assessment Ross Parker, Ph.D. Mentor: Trent Dougherty, Ph.D. The argument from divine hiddenness against God’s existence has become one of the most important atheistic arguments in the contemporary philosophical literature. In this dissertation I offer an assessment of this argument. Specifically, I provide some needed conceptual clarity to the discussion of the argument from hiddenness and respond to various strands of the contemporary discussion of the argument. In the first chapter I argue that the argument from hiddenness is best understood as a family of arguments, and I give an account of what binds these arguments together. In the second chapter, after surveying extant presentations of arguments from hiddenness, I provide a conceptual map of various ways an argument from hiddenness can be presented. I then in the third chapter I develop a Schellenbergian argument from the existence of inculpable nonbelief which serves as the focus of my critical evaluation. In the fourth chapter I address the relationship between that argument from evil and the argument from hiddenness. Chapters five and six offer critiques of two recent attempts to respond to the argument from evil. Then in the seventh chapter I develop my own response to the Schellenbergian argument from hiddenness, arguing that God would be justified in allowing temporary inculpable favorably disposed nonbelief because of various goods that make possible or are made possible by the existence of nonbelief. Copyright © 2014 by Ross -

Farah Nassif 2019 a God Who Is Present.Pdf

A God Who is Present: A Christological and Anthropological Study of the Presence of God in Pope Benedict XVI’s Jesus of Nazareth Nassif Farah Student number: 8810637 Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Theology, Saint Paul University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Theology Supervisor: Dr. Karl Hefty Ottawa, Canada March 7, 2019 © Nassif Farah, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 Farah 1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 Chapter One ............................................................................................................................... 9 The Reception of Jesus of Nazareth and the Problem of Revelation ............................................ 9 §1. Revelation: God’s Action and Presence in History ........................................................ 9 §2. Initial Scholarly Reception .......................................................................................... 11 §3. Ratzinger’s Concern: Church, Scripture, and God’s Active Word ................................ 22 Chapter Two ............................................................................................................................. 28 Jesus of Nazareth: God’s Enduring Presence............................................................................. 28 §4. A Perfect Revelation: Historical and Sacramental ........................................................ 28 Part One: The Authentic -

Ordinary Morality Implies Atheism

ORDINARY MORALITY IMPLIES ATHEISM STEPHEN MAITZEN Acadia University Abstract. I present a “moral argument” for the non-existence of God. Theism, I argue, can’t accommodate an ordinary and fundamental moral obligation acknowledged by many people, including many theists. My argument turns on a principle that a number of philosophers already accept as a constraint on God’s treatment of human beings. I defend the principle against objections from those inclined to reject it. In his Elements of Moral Philosophy, James Rachels remarks that “it isn’t unusual for priests and ministers to be treated as moral experts.... Why [he asks] are clergymen regarded in this way? ... In popular thinking, morality and religion are inseparable: People commonly believe that morality can be understood only in the context of [theistic] religion.”1 This popular association of morality with theism may explain why atheists showed up as the single most distrusted minority group in a recent opinion survey conducted in the United States, much to the surprise of those who conducted the survey.2 Despite that popular association, I’ll argue that theism and ordinary morality are incompatible: theism can’t accommodate an ordinary and fundamental moral obligation acknowledged by many people, including many theists. My argument turns on a principle that a number of philosophers already accept as a constraint on any plausible theodicy. I’ll defend the principle against objections from those inclined 1 James Rachels, Elements of Moral Philosophy (Boston: McGraw-Hill, 3d. ed., 1999), 53–54. Although Rachels gives the title “Does Morality Depend on Religion?” to the relevant chapter of his book, he restricts his discussion of religion to (Christian) theism: “In discussing the connection (or lack of connection) between morality and religion, I will focus on one religion in particular, Christianity” (55). -

Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Religion Contemporary Debates in Philosophy

Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Religion Contemporary Debates in Philosophy In teaching and research, philosophy makes progress through argumentation and debate. Contemporary Debates in Philosophy presents a forum for students and their teachers to follow and participate in the debates that animate philosophy today in the western world. Each volume presents pairs of opposing viewpoints on contested themes and topics in the central subfields of philosophy. Each volume is edited and introduced by an expert in the field, and also includes an index, bibliography, and suggestions for further reading. The opposing essays, commissioned especially for the volumes in the series, are thorough but accessible presentations of opposing points of view. 1. Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Religion edited by Michael L. Peterson and Raymond J. VanArragon 2. Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Science edited by Christopher Hitchcock 3. Contemporary Debates in Epistemology edited by Matthias Steup and Ernest Sosa 4. Contemporary Debates in Applied Ethics edited by Andrew I. Cohen and Christopher Heath Wellman Forthcoming Contemporary Debates are in: Aesthetics edited by Matthew Kieran Cognitive Science edited by Robert Stainton Metaphysics edited by Ted Sider, Dean Zimmerman, and John Hawthorne Moral Theory edited by James Dreier Philosophy of Mind edited by Brian McLaughlin and Jonathan Cohen Social Philosophy edited by Laurence Thomas CONTEMPORARY DEBATES IN PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION Edited by Michael L. Peterson and Raymond J. VanArragon © 2004 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148‐5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Michael L. -

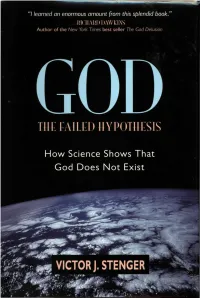

God: the Failed Hypothesis—How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist

GOD GOD THE FAILED HYPOTHESIS How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist VICTOR J. STENGER Prometheus Books 59 John Glenn Drive Amherst, New York 14228-2197 Published 2007 by Prometheus Books God: The Failed Hypothesis—How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist. Copyright © 2007 by Victor J. Stenger. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a Web site without prior written permission of the publisher, ex cept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to Prometheus Books 59 John Glenn Drive Amherst, New York 14228-2197 VOICE: 716-691-0133, ext. 207 FAX: 716-564-2711 WWW.PROMETHEUSBOOKS.COM 11 10 09 08 07 5 4 3 2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stenger, Victor J., 1935- God : the failed hypothesis : how science shows that God does not exist / Victor J. Stenger. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-59102-481-1 (alk. paper) 1. Religion and science. 2. God—Proof. 3. Atheism. I. Title. BL240.3.S738 2007 212'. 1— dc22 2006032867 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 7 Preface 9 Chapter 1: Models and Methods 21 Chapter 2: The Illusion of Design 47 Chapter 3: Searching for a World beyond Matter 77 Chapter 4: Cosmic Evidence 113 Chapter 5: The Uncongenial Universe 137 Chapter 6: The Failures of Revelation 169 5 6 CONTENTS Chapter 7: Do Our Values Come from God? 193 Chapter 8: The Argument from Evil 215 Chapter 9: Possible and Impossible Gods 227 Chapter 10: Living in the Godless Universe 243 Bibliography 261 Index 283 About the Author 293 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS s with my previous books, I have benefited greatly from Acomments and corrections provided by a large number of individuals with whom I communicate regularly on the Internet. -

Do Children Need Religion?

Do Children Need Religion? 42 74957 SUMMER 1994, VOL. 14, NO. 3 ISSN 0272-0701 Free Contents Editor: Paul Kurtz Senior Editors: Vern Bullough, Thomas Flynn, Gerald Larue, Gordon Stein 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR Executive Editor: Timothy J. Madigan Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski 4 EDITORIALS Contributing Editors: Supreme Court Hears Arguments in Kiryas Joel School Case, Robert S. Alley, Joe E. Barnhart, David Berman, Lisa H. Thurau / NBC's Cynically Skewed Reporting on the `Power H. James Birx, Jo Ann Boydston, Bonnie Bullough, Paul Edwards, Albert Ellis, Roy P. Fairfield, Charles of Prayer,' Gary P. Posner / Catholic-Evangelical Compact W. Faulkner, Antony Flew, Levi Fragell, Adolf Showcases Newhaus's Rising Star, Tom Flynn / The Crisis of Grünbaum, Marvin Kohl, Jean Kotkin, Thelma Lavine, Tibor Machan, Ronald A. Lindsay, Michael the Black Religious Intellectual, Norm Allen, Jr. / Some Lessons Martin, Delos B. McKown, Lee Nisbet, John Novak, for Humanists, Paul Kurtz / The Waco Tragedy, James A. Haught Skipp Porteous, Howard Radest, Robert Rimmer, Michael Rockier, Svetozar Stojanovic, Thomas / Oral Roberts on Jim Bakker, Martin Gardner / Baring the Szasz, V. M. Tarkunde, Richard Taylor, Rob Threat, Skipp Porteous Tielman 17 ON THE BARRICADES Associate Editors: Janey L. Levy and Molleen Matsumura DO CHILDREN NEED RELIGION? Editorial Associates: Doris Doyle, Thomas Franczyk, Roger Greeley, 18 Introduction Andrea Szalanski Steven L. Mitchell, Warren Allen Smith 19 'So, What Do You Teach Your Kids?' Tom Malone Chairman, CODESH, Inc.: Paul Kurtz 21 `I'm on Fire to Explain' Kenneth Marsalek Chief Development Officer: James Kimberly 22 Ingersoll on Children and Morality Roger Greeley Public Relations Director: Norm R.