Accessing the Iraqi Jewish Archive Dina Herbert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Wave of Progressives Shows Israel Criticism Isn't Taboo Anymore

Jewish Federation of NEPA Non-profit Organization 601 Jefferson Ave. U.S. POSTAGE PAID The Scranton, PA 18510 Permit # 184 Watertown, NY Change Service Requested Published by the Jewish Federation of Northeastern Pennsylvania VOLUME XI, NUMBER 14 JULY 26, 2018 A wave of progressives shows Israel criticism isn’t taboo anymore an “intersectional feminist” table criticism, the general trends it notes ANALYSIS and Israel an apartheid have been shown elsewhere. regime. In Virginia’s 5th Some credit Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) BY CHARLES DUNST Congressional District, with normalizing such criticism of Israel. NEW YORK (JTA) – After Alexan- Democratic nominee Leslie While the 2016 Democratic presidential dria Ocasio-Cortez shocked the political Cockburn is the co-author, candidate defined himself as “100 percent world by defeating longtime New York along with her husband, of pro-Israel,” he recently called on the U.S. Rep. Joseph Crowley in a Democratic “Dangerous Liaison: The to adopt a more balanced policy toward primary in June, Democratic National Inside Story of the U.S.-Is- Israel and the Palestinians. In late March, Committee Chairman Tom Perez quickly raeli Covert Relationship,” Sanders’ office posted three videos to Ilhan Omar at the premiere aligned himself with the former political a scathing 1991 attack on social media criticizing Israel for what outsider, saying on a radio show that “she the Jewish state. of “Time For Ilhan,” a film he deemed its excessive use of force in Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez about her congressional represents the future of our party.” “It seems to me that some appeared on “Meet the Gaza and the Trump administration for If so, that future appears to include criticism of Israel is part of a seat run, during the 2018 not intervening during the border clashes. -

The Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation 9 Annual

The Lawyers' Committee for Cultural Heritage Preservation 9th Annual Conference Friday, April 13, 2018 8:00am-6:30pm Georgetown University Law Center McDonough Hall, Hart Auditorium 600 New Jersey Ave NW, Washington, DC 20001 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Panel 1: Claiming and Disclaiming Ownership: Russian, Ukrainian, both or neither? Panel 2: Whose Property? National Claims versus the Rights of Religious and Ethnic Minorities in the Middle East Panel 3: Protecting Native American Cultural Heritage Panel 4: Best Practices in Acquiring and Collecting Cultural Property Speaker Biographies CLE MATERIALS FOR PANEL 1 Laws/ Regulations Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-confiscated Art (1998) https://www.state.gov/p/eur/rt/hlcst/270431.htm Articles/ Book Chapters/ White Papers Quentin Byrne-Sutton, Arbitration and Mediation in Art-Related Disputes, ARBITRATION INT’L 447 (1998). F. Shyllon, ‘The Rise of Negotiation (ADR) in Restitution, Return and Repatriation of Cultural Property: Moral Pressure and Power Pressure’ (2017) XXII Art Antiquity and Law pp. 130-142. Bandle, Anne Laure, and Theurich, Sarah. “Alternative Dispute Resolution and Art-Law – A New Research Project of the Geneva Art-Law Centre.” Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2011): 28 – 41 http://www.jiclt.com/index.php/jiclt/article/view/124/122 E. Campfens “Whose cultural heritage? Crimean treasures at the crossroads of politics, law and ethics”, AAL, Vol. XXII, issue 3, (Oct. 2017) http://www.iuscommune.eu/html/activities/2017/2017-11-23/workshop_3_Campfens.pdf Anne Laure Bandle, Raphael Contel, Marc-André Renold, “Case Ancient Manuscripts and Globe – Saint-Gall and Zurich,” Platform ArThemis (http://unige.ch/art-adr), Art-Law Centre, University of Geneva. -

1 Is the United States Returning Stolen Cultural

Is the United States Returning Stolen Cultural Property to the Countries that Committed the Theft in the First Place? Treatment of the Iraqi Jewish Archive and Other Property Under U.S. Statutes and Memoranda of Understanding with Algeria, Syria, Egypt and Libya and proposed with Yemen By: Carole Basri as of October 15, 2019 (based on my article written in the American Bar Association Section of International Law, Fall 2018, Art & Cultural Heritage Law Newsletter) In May 2003, over 2700 Jewish books and tens of thousands of documents, records, and religious artifacts were discovered by a U.S. Army team in the flooded basement of the Iraqi intelligence headquarters. The written records provide a better understanding of the 2700 year- old Iraqi Jewish community. The Jewish Iraqi Archive was brought to the U.S. to be preserved, cataloged, and digitized, and has been exhibited in various cities for several years. Based on an agreement signed on August 19, 2003 between the Coalition Provisional Authority and the National Archives and Records Administration,1 and extended by the U.S. Government in an Executive Order by President Obama, the Iraqi Jewish Archive was to have been returned to Iraq after September 2018. Then on a parallel track, but unbeknownst to the Iraqi Jewish community, Congress amended the Emergency Protection for Iraqi Cultural Antiquities Act of 2004 in 2008 to include import restrictions on Jewish artifacts. These import restrictions included Torahs and other Jewish artifacts made on or before 1990.2 After this, the U.S. State Department put together separate Memoranda of Understanding regarding Jewish religious and cultural artifacts from Algeria, Syria, Egypt and Libya. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 4 The Iraq & Iran Issue Iran and Iraq: Demography beyond the Jewish Past 6 Sergio DellaPergola AJS, Ahmadinejad, and Me 8 Richard Kalmin Baghdad in the West: Migration and the Making of Medieval Jewish Traditions 11 Marina Rustow Jews of Iran and Rabbinical Literature: Preliminary Notes 14 Daniel Tsadik Iraqi Arab-Jewish Identities: First Body Singular 18 Orit Bashkin A Republic of Letters without a Republic? 24 Lital Levy A Fruit That Asks Questions: Michael Rakowitz’s Shipment of Iraqi Dates 28 Jenny Gheith On Becoming Persian: Illuminating the Iranian-Jewish Community 30 Photographs by Shelley Gazin, with commentary by Nasrin Rahimieh JAPS: Jewish American Persian Women and Their Hybrid Identity in America 34 Saba Tova Soomekh Engagement, Diplomacy, and Iran’s Nuclear Program 42 Brandon Friedman Online Resources for Talmud Research, Study, and Teaching 46 Heidi Lerner The Latest Limmud UK 2009 52 Caryn Aviv A Serious Man 53 Jason Kalman The Questionnaire What development in Jewish studies over the last twenty years has most excited you? 55 AJS Perspectives: The Magazine of the President Please direct correspondence to: Association for Jewish Studies Marsha Rozenblit Association for Jewish Studies University of Maryland Center for Jewish History Editors 15 West 16th Street Matti Bunzl Vice President/Publications New York, NY 10011 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Jeffrey Shandler Rachel Havrelock Rutgers University Voice: (917) 606-8249 University of Illinois at Chicago Fax: (917) 606-8222 Vice President/Program E-Mail: [email protected] Derek Penslar Web Site: www.ajsnet.org Editorial Board Allan Arkush University of Toronto Binghamton University AJS Perspectives is published bi-annually Vice President/Membership by the Association for Jewish Studies. -

Rescue Or Return: the Fate of the Iraqi Jewish Archive Bruce P

International Journal of Cultural Property (2013) 20:175–200. Printed in the USA. Copyright © 2013 International Cultural Property Society doi:10.1017/S0940739113000040 Rescue or Return: The Fate of the Iraqi Jewish Archive Bruce P. Montgomery* Abstract: Shortly following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, an American mobile exploitation team was diverted from its mission in hunting for weapons for mass destruction to search for an ancient Talmud in the basement of Saddam Hussein’s secret police (Mukhabarat) headquarters in Baghdad. Instead of finding the ancient holy book, the soldiers rescued from the basement flooded with several feet of fetid water an invaluable archive of disparate individual and communal documents and books relating to one of the most ancient Jewish communities in the world. The seizure of Jewish cultural materials by the Mukhabarat recalled similar looting by the Nazis during World War II. The materials were spirited out of Iraq to the United States with a vague assurance of their return after being restored. Several years after their arrival in the United States for conservation, the Iraqi Jewish archive has become contested cultural property between Jewish groups and the Iraqi Jewish diaspora on the one hand and Iraqi cultural officials on the other. This article argues that the archive comprises the cultural property and heritage of the Iraqi Jewish diaspora. I. INTRODUCTION In early May 2003, a U.S. mobile exploitation team (MET) was diverted from its mission in hunting for weapons of mass destruction to rescue an ancient Tal- mud, a Jewish holy book, in the basement of the Mukhabarat, Saddam Hussein’s secret police headquarters. -

Iraqi Jewish Archives

24 Shevat 5774 25 January 2014 KOL MEVASSER The Iraqi Jewish Archives Update RESOLUTION strongly recommending that by Joseph Dabby the United States renegotiate the return of KJ Schedule the Iraqi Jewish Archive to Iraq. Parashat Mishpatim Members of Congress Ileana Ross-Lehtinen and Steve Israel have received no response Whereas, before the mid-20th century, Erev Shabbat / Shabbat Eve Friday, January 24th to their bi-partisan letter to Secretary of Baghdad had been a center of Jewish life, Shaharit/Morning Prayer ........................ 6:30 am State John Kerry. They are now writing culture, and scholarship, dating back to 721 Shir Hashirim .......................................... 4:35 pm again to the State Department with six BC; Shabbat Candlelighting .......................... 4:57 pm Minhah/Arbith ......................................... 4:57 pm definitive questions that they seek answers for – including the option of not returning the Whereas, as recently as 1940, Jews made Yom Shabbat / Shabbat Day Iraqi archives to Iraq. up 25 percent of Baghdad’s population; Saturday, January 25th Shaharit/Morning Prayer ........................ 8:30 am Senators Toomey and Blumenthal intro- Birkat Hachodesh for Adar I ..... during services Whereas, in the 1930’s and 1940’s, under Lunch & Learn with Rabbi Daniel Bouskila .... duced a Senate Resolution on January 16, the leadership of Rasheed Ali, anti-Jewish 2014, co-sponsored by Senators Schumer, .......... following services, approximately 12 noon discrimination increased drastically, includ- Minha, Seudah Shlisheet, Arvit .............. 4:00 pm Kirk, Cardin, Rubio, Roberts, Kaine, Boxer ing the June 1-2, 1941, Farhud pogrom, in Motzei Shabbat / Havdallah.................... 6:01 pm and Menendez. which nearly 180 Jews were killed; Weekdays Following is a copy of the Resolution (which Sunday , January 26th Whereas, in 1948, Zionism was added to Shaharit ................................................ -

Israel Is the Star at a National Security Conference in Mississippi

Jewish Federation of NEPA Non-profit Organization 601 Jefferson Ave. U.S. POSTAGE PAID The Scranton, PA 18510 Permit # 184 Watertown, NY Change Service Requested Published by the Jewish Federation of Northeastern Pennsylvania VOLUME XI, NUMBER 6 MARCH 22, 2018 Israel is the star at a national security conference in Mississippi BY BEN SALES BILOXI, MS (JTA) – A homeland se- curity conference took place in a southern Mississippi town with an Air Force base At right: Mississippi and a shipbuilding yard. Among those in Gov. Phil Bryant at attendance were the commandant of the a press conference U.S. Coast Guard; a general from India, with Israeli officials the world’s second-largest country; and at the Homeland representatives from Taiwan and South Defense and Security Korea, a U.S. ally in a key trouble spot. Summit in Biloxi,MS, But Israel was the star. on March 13. (Photo The International Homeland Defense by Ben Sales) and Security Summit, organized by the state government, was held March 13 in this Gulf Coast city far from any Jewish population center, in a state the local Is- the conference, whose organizers paid They were there to expand into the U.S. migrants and weapons across the water. raeli consul visits only twice a year. But for JTA’s flight to Biloxi along with hotel market and introduce themselves to local They discussed natural disasters like representatives of 16 Israeli companies costs. “They have a tough neighborhood officials and private companies. Hurricane Katrina – its effects are still attended, along with a delegation from they live in.” One tool, Smart Shooter, promises visible here – and how climate change its Defense Ministry and arms industry. -

National Archives at Kansas City Newsletter

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVE S AT KANSAS CITY June 2015 Dr. John Curatola to Discuss Inside This Issue Props and Pin-Ups: Nose Art in World War II IRAQI JEWISH 1-4 HERITAGE EXHIBIT & On Wednesday, June 3 at 6:30 p.m., the National Archives at Kansas City will host PROGRAM SERIES Dr. John Curatola who will discuss Props and Pin-Ups: Nose Art in World War II. A free light reception will precede the lecture at 6:00 p.m. GEMS FOR 5 GENEALOGISTS The use of nose art was common on military aircraft during the Second World War. HIDDEN TREASURES 6-7 Painted on the fuselages of many of the FROM THE STACKS belligerent air forces aircraft, these stand- alone pieces of art reflected aircrews’ values and attitudes. Messages and pictures painted on these aircraft are not only a rich military Upcoming Events legacy, but provide insight into the time, Unless noted, all events temperament, and men who flew and are held at the maintained them. Curatola will address the National Archives various influences, national trends, and 400 West Pershing Road Kansas City, MO 64108 Above: Image courtesy of the U.S. Army general themes of this unique element of military history. The presentation will show Command and General Staff College and JUNE 3 - 6:30 P.M. ArmyAirForces.com. nose art in its original form and in historical context, which includes partial nudity. LECTURE: PROPS AND PIN -UPS: NOSE ART IN To make a reservation for this free program email [email protected] or call 816-268-8010. -

The Jewish Theological Seminary Invites You To

The Jewish Theological Seminary invites you to “Johanna Spector’s Impact on Jewish Musicology: Encountering and Documenting Jewish Musical Culture from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia” A Conversation with Dr. Geoffrey Goldberg Wednesday, November 20, 2013 12:15 to 1:15 p.m. The Jewish Theological Seminary Berman Board Room II 3080 Broadway (at 122nd Street), New York City ABOUT THE PROGRAM As part of the project to process and publicize the archival collection of the ethnomusicologist and ethnologist Dr. Johanna Spector, Dr. Geoffrey Goldberg—who studied with Dr. Spector at JTS—will present a brown bag lunch program discussing her influence on the study of Jewish music from non- Western communities. Dr. Spector’s groundbreaking research has assured that dwindling traditions from India, Yemen, Persia, Egypt, Syria, and other remote communities are well documented through recordings, photographs, and films. ABOUT THE SPEAKER Dr. Geoffrey Goldberg is rabbi of the Jewish Center of Forest Hills West in Forest Hills, New York. Both an experienced rabbi and musicologist, Dr. Goldberg has taught at universities such as the University of Rochester, Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion, and Tel-Aviv University. His publications include a number of articles on the history of congregational music in German and US synagogues. Dr. Goldberg received a BA in Medieval and Modern History from the University of Birmingham in Birmingham, England; rabbinic ordination from Leo Baeck College in London; cantorial investiture at JTS; an MA in Musicology from New York University; and a PhD in Jewish Musicology from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Admission is free, but reservations are required. -

Preserving the "Iraqi Jewish Archive"

Preserving the “Iraqi Jewish Archive” By Doris A. Hamburg and Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler ne of the rewards of our work at the and books, including those damaged during ONational Archives in preserving the an emergency. records of the federal government comes from learning the fascinating human sto ries that relate to the records. Arriving in Baghdad, This is the story of how the Na Stabilizing the Records tional Archives Preservation Pro Arriving in Baghdad via a C-130 cargo plane, grams staff was called upon to the first stop for the conservation team was rescue and preserve records and Saddam Hussein’s ornate Republican Guard books that came from the once- Palace. Next, we went to a nearby warehouse vibrant Iraqi Jewish community on the bank of the Tigris River, where Reserve and had been damaged during Maj. Corinne Wegener oversaw 27 metal the 2003 war in Iraq. trunks filled with the distorted, wet, and In June 2003, upon receiving moldy books and documents, primarily in an urgent request for help from Hebrew and Arabic. the Coalition Provisional Author As we climbed the ladder into the freezer ity in Baghdad, the National truck holding the trunks, we noticed that Archives arranged for us, as two the smell of mold permeated everything. of the agency’s preservation experts, Freezing the collection had stopped further to travel to Baghdad to assess an mold growth, however, and provided time to important group of very damaged plan the next preservation steps. and moldy books and docu Each trunk held a largely frozen mass of ments that had been rescued documents and books. -

Archives & Records in Armed Conflict

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research CUNY School of Law 2010 Archives & Records in Armed Conflict: International Law and the Current Debate Over Iraqi Records and Archives Douglas Cox CUNY School of Law How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cl_pubs/149 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ARCHIVES AND RECORDS IN ARMED CONFLICT: INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE CURRENT DEBATE OVER IRAQI RECORDS AND ARCHIVES Douglas Cox+ I. IN TRODUCTION ........................................................................... 1002 II. THE NATURE OF RECORDS AND ARCHIVES IN WAR .................. 1004 A. ARCHIVES, RECORDS, AND DOCUMENTS ............................. 1004 B. THE VALUE OF ARCHIVES AND RECORDS IN WAR .............. 1005 1. Intelligence, Military, and Political Value ...................... 1006 2. Legal and Administrative Value ......................................... 1007 3. Cultural and H istorical Value ............................................ 1008 C. THE CHALLENGE OF LEGAL PROTECTION ........................... 1009 III. RECORDS AND ARCHIVES IN INTERNATIONAL LAW ................. 1010 A. RECORDS AND ARCHIVES AS CULTURAL PROPERTY ........... 1012 B. THE LEGAL REGIME FOR RECORDS AND ARCHIVES IN WAR 1016 1. Obligations Priorto Armed Conflict ............................ 1016 2. Rights -

Sample Issue

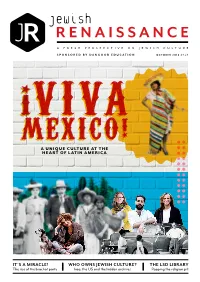

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION OCTOBER 2018 £7.25 VIVAVIVA MEXICO!MEXICO! A UNIQUE CULTURE AT THE HEART OF LATIN AMERICA IT’S A MIRACLE! WHO OWNS JEWISH CULTURE? THE LSD LIBRARY The rise of the brachot party Iraq, the US and the hidden archives Popping the religion pill JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 OCTOBER 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the July issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW First service in 500 6 years for Lorca synagogue; chocolate menorot (yum); YIVO opens in London. FEATURE Marseille’s unsung hero: 10 Elisabeth Blanchet uncovers the wartime story of Varian Fry. FEATURE When the nun met the 12 rabbi: Deborah Freeman visits the German Bible study centre where Christians, Muslims and Jews debate together. PASSPORT Mexico: We uncover 14 a history of secret villages; fiery revolutionaries and Yiddish activists; meet Mexico City’s first woman – and Jewish – mayor; and hear from the cultural movers and shakers who are putting this Latin American country on the map. CONTENTS FILM The UK Jewish Film Festival is 32 coming to town! We review the top docs that are set to make waves this year. CAROL ISAACS; FROM ALTERED STATES, PUBLISHED BY ANTHOLOGY EDITIONS ANTHOLOGY PUBLISHED BY STATES, FROM ALTERED CAROL ISAACS; © THEATRE Canada is the setting 34 for Old Stock’s story of immigration 14 and love.