The Development in the Sturdy of History And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 89 Area & Population

Table :- 1 89 AREA & POPULATION AREA, POPULATION AND POPULATION DENSITY OF PAKISTAN BY PROVINCE/ REGION 1961, 1972, 1981 & 1998 (Area in Sq. Km) (Population in 000) PAKISTAN /PROVINCE/ AREA POPULATION POPULATION DENSITY/Sq: Km REGION 1961 1972 1981 1998 1961 1972 1981 1998 Pakistan 796095 42880 65309 84254 132351 54 82 106 166 Total % Age 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 Sindh 140914 8367 14156 19029 30440 59 101 135 216 % Age share to country 17.70 19.51 21.68 22.59 23.00 Punjab 205345 25464 37607 47292 73621 124 183 230 358 % Age share to country 25.79 59.38 57.59 56.13 55.63 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 74521 5731 8389 11061 17744 77 113 148 238 % Age share to country 9.36 13.37 12.84 13.13 13.41 Balochistan 347190 1353 2429 4332 6565 4 7 12 19 % Age share to country 43.61 3.16 3.72 5.14 4.96 FATA 27220 1847 2491 2199 3176 68 92 81 117 % Age share to country 3.42 4.31 3.81 2.61 2.40 Islamabad 906 118 238 340 805 130 263 375 889 % Age share to country 0.11 0.28 0.36 0.4 0.61 Source: - Population Census Organization, Government, of Pakistan, Islamabad Table :- 2 90 AREA & POPULATION AREA AND POPULATION BY SEX, SEX RATIO, POPULATION DENSITY, URBAN PROPORTION HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE OF BALOCHISTAN 1998 CENSUS Population Pop. Avg. Growth DIVISION / Area Sex Urban Pop. Both density H.H rate DISTRICT (Sq.km.) Male Female ratio Prop. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Sibi District Education Plan (2016-17 to 2020-21)

Sibi District Education Plan (2016-17 to 2020-21) Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS 1 LIST OF FIGURES 3 LIST OF TABLES 4 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 METHODOLOGY & PROCESS 7 2.1 METHODOLOGY 7 2.1.1 DESK RESEARCH 7 2.1.2 CONSULTATIONS 7 2.1.3 STAKEHOLDERS INVOLVEMENT 7 2.2 PROCESS FOR PLANS DEVELOPMENT: 8 2.2.1 SECTOR ANALYSIS: 8 2.2.2 IDENTIFICATION AND PRIORITIZATION OF STRATEGIES: 9 2.2.3 FINALIZATION OF DISTRICT PLANS: 9 3 SIBI DISTRICT PROFILE 10 3.1 POPULATION 11 3.2 ECONOMIC ENDOWMENTS 11 3.3 POVERTY & CHILD LABOR: 12 3.4 STATE OF EDUCATION 12 4 ACCESS & EQUITY 16 4.1 EQUITY AND INCLUSIVENESS 21 4.2 IMPORTANT FACTORS 22 4.2.1 SCHOOL AVAILABILITY AND UTILIZATION 22 4.2.2 MISSING FACILITIES AND SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT 24 4.2.3 POVERTY 24 4.2.4 PARENT’S ILLITERACY 24 4.2.5 ALTERNATE LEARNING PATH 25 4.3 OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES 26 5 DISASTER RISK REDUCTION 31 5.1 OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES 32 6 QUALITY AND RELEVANCE OF EDUCATION 33 6.1 SITUATION 33 6.2 DISTRICT LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS 34 6.3 OVERARCHING FACTORS FOR POOR EDUCATION 36 6.4 DISTRICT RELATED FACTORS OF POOR QUALITY 37 6.4.1 OWNERSHIP OF QUALITY IN EDUCATION 37 6.4.2 CAPACITY OF FIELD TEAMS 37 6.4.3 ACCOUNTABILITY MODEL OF HEAD TEACHERS 37 6.4.4 NO DATA COMPILATION AND FEEDBACK 37 6.4.5 CURRICULUM IMPLEMENTATION AND FEEDBACK 38 6.4.6 TEXTBOOKS DISTRIBUTION AND FEEDBACK 38 6.4.7 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT 38 6.4.8 TEACHERS AVAILABILITY 39 6.4.9 ASSESSMENTS 39 6.4.10 EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION (ECE) 39 6.4.11 AVAILABILITY AND USE OF LIBRARIES & LABORATORIES 39 6.4.12 SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT 40 -

A Solar Developer's Guide to Pakistan

A Solar Developer’s Guide to Pakistan IN PARTNERSHIP WITH: Acknowledgements This Guide was developed as part of the IFC Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Renewable Energy Development Support Advisory program, funded by AusAid, Japan, and The Netherlands for activities in Pakistan. The overall goal of this multi-year program is to enhance the scale up and development of renewable and clean energy in MENA by supporting developers and investors in MENA markets, increasing overall market awareness and understanding, and facilitating public-private dialogue. The Guide was prepared under the overall guidance of Bryanne Tait, IFC’s Regional Lead for Energy and Resource Efficiency Advisory, Middle East and North Africa. We acknowledge the significant contributions of Sohail Alam, IFC Energy Specialist and Alice Cowman, Renewable Energy Specialist, who has been commissioned by IFC to carry out the desk research, drafting and interviews. We would like to thank the Pakistan Alternative Energy Development Board, National Electric Power Regulatory Authority, National Transmission and Distribution Company, the Province of Punjab and the Province of Sindh, who contributed greatly to the research and study for this guide through interviews and provision of information and documents. IFC would also like to express its sincere appreciation to RIAA Barker Gillette, Ernst & Young, and Eversheds, who contributed to the drafting of the guide. Solar resource maps and GIS expertise were kindly provided by AWS Truepower and colleagues from the World Bank respectively, including support from the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP). Certain mapping data was obtained from OpenStreetMap, and copyright details for this can be found at http://www.openstreetmap.org/copyright. -

15 the Regions of Sind, Baluchistan, Multan

ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1 THE REGIONS OF SIND . 15 THE REGIONS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN, MULTAN AND KASHMIR: THE HISTORICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC SETTING* N. A. Baloch and A. Q. Rafiqi Contents THE RULERS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN AND MULTAN (750–1500) ....... 298 The cAbbasid period and the Fatimid interlude (mid-eighth to the end of the tenth century) ...................................... 298 The Period of the Ghaznavid and Ghurid Sultanates (eleventh and twelfth centuries) . 301 The era of the local independent states ......................... 304 KASHMIR UNDER THE SULTANS OF THE SHAH¯ MIR¯ DYNASTY ....... 310 * See Map 4, 5 and 7, pp. 430–1, 432–3, 437. 297 ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1 The cAbbasid period Part One THE RULERS OF SIND, BALUCHISTAN AND MULTAN (750–1500) (N. A. Baloch) From 750 to 1500, three phases are discernible in the political history of these regions. During the first phase, from the mid-eighth until the end of the tenth century, Sind, Baluchis- tan and Multan – with the exception of the interlude of pro-Fatimid ascendency in Mul- tan during the last quarter of the tenth century – all remained politically linked with the cAbbasid caliphate of Baghdad. (Kashmir was ruled, from the eighth century onwards, by the local, independent, originally non-Muslim dynasties, which had increasing political contacts with the Muslim rulers of Sind and Khurasan.) During the second phase – the eleventh and twelfth centuries – all these regions came within the sphere of influence of the powers based in Ghazna and Ghur. During the third phase –from the thirteenth to the early sixteenth century – they partly became dominions of the Sultanate of Delhi, which was in itself an extension into the subcontinent of the Central Asian power base. -

The People and Land of Sindh by Ahmed Abdullah

THE PEOPLE AD THE LAD OF SIDH Historical perspective By: Ahmed Abdullah Reproduced by Sani Hussain Panhwar Los Angeles, California; 2009 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 COTETS Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 The People and the Land of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 The Jats of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Arab Period .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 Mohammad Bin Qasim’s Rule .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Missionary Work .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 15 Sindh’s Progress Under Arabs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 17 Ghaznavid Period in Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Naaseruddin Qubacha .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 23 The Sumras and the Sammas .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 The Arghans and the Turkhans .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 The Kalhoras and Talpurs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 ITRODUCTIO This material is taken from a book titled “The Historical Background of Pakistan and its People” written by Ahmed Abdulla, published in June 1973, by Tanzeem Publishers Karachi. The original -

Essays on the History of Sindh.Pdf

Essays On The History of Sindh Mubarak Ali Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2019) CONTENTS Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 Historiography of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Nasir Al-Din Qubachah (1206-1228) .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Lahribandar: A Historical Port of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. 22 The Portuguese in Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 Sayyid Ahmad Shahid In Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. 35 Umarkot: A Historic City of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. 39 APPENDIX .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 49 Relations of Sindh with Central Asia .. .. .. .. .. .. 70 Reinterpretation of Arab Conquest of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. 79 Looters are 'great men' in History! .. .. .. .. .. .. 81 Index .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 85 INTRODUCTION The new history creates an image of the vanquished from its own angle and the defeated nation does not provide any opportunity to defend or to correct historical narrative that is not in its favour. As a result, the construction of the history made by the conquerors becomes valid without challenge. A change comes when nations fight wars of liberation and become independent after a long and arduous struggle. During this process, leaders of liberation movements are required to use history in order to fulfil their political ends. Therefore, attempts are made to glorify the past to counter the causes of their subjugation. A comprehensive plan is made to retrieve their lost past and reconstruct history to rediscover their traditions and values and strengthen their national identity. However, in some cases, subject nations are so much integrated to the culture of their conquerors that they lose their national identity and align themselves with foreign culture. They accept their version of history and recognize the aggressors as their heroes who had liberated them from their inefficient rulers and, after elimination of their out- dated traditions, introduced them to modern values and new ideas. -

DC-3, Unit-11, Bi

Study Material for Sem-II , History(hons.) DC-3 ,Unit-II, b.i ARAB INVASION OF SIND Introduction Rise of Islam is an important incident in the history of Islam. Prophet Muhammad was not only the founder of a new religion, but he was also the head of a city-state. Muhammad left no male heir. On his death claims were made on behalf of his son-in-law and cousin Ali, but senior members of the community elected as their leader or caliph, the Prophet's companion, Abu Bakr, who was one of the earliest converts to Islam. Abu Bakr died after only two years in office, and was succeeded by Umar (r. 634-644 ), under whose leadership the Islamic community was transformed into a vast empire. Umar was succeeded by Usman (r. 644-656), who was followed by Ali (r. 656661), the last of the four "Righteous Caliphs." Owing to his relationship with the Prophet as well as to personal bravery, nobility of character, and intellectual and literary gifts, Caliph Ali occupies a special place in the history of Islam, but he was unable to control the tribal and personal quarrels of the Arabs. After his death, Muawiyah (r. 661- 680), the first of the Umayyad caliphs, seized power and transferred the seat of caliphate from Medina to Damascus. Three years later the succession passed from Muawiyah's grandson to another branch of the Umayyad dynasty, which continued in power until 750. During this period the Muslim armies overran Asia Minor, conquered the north coast of Africa, occupied Spain, and were halted only in the heart of France at Tours. -

Sindh Is One of the Ancient Regions of the World. It Now Forms Integral Part of Pakistan. ―Sindh Or Indus Valley Proper Is

Grassroots Vol.50, No.II July-December 2016 A GLIMPSE IN TO THE CONDITIONS OF SINDH BEFORE ARAB CONQUEST Farzana Solangi Muhammad Ali Laghari Nasrullah Kabooro ABSTRACT Ancient history of Sindh dates back to Bronze age civilization, popularly known as Indus valley civilization, which speaks of glorious past of Sindh. Sindh was a vast country before the invasion of Arabs. King was the administrative head in the political setup of the country. Next in power to the king was the minister who exercised great influence over the monarch. King was also the commander of his army. Though king acted as the supreme judge of the country, yet he followed systematic manner in dispensing the justice. The society was divided into two broad classes. The sophisticated upper class consisted of ruling rich and their poets and priests. The lower class consisting of peasants, weavers, tanners, carpenter smiths and itinerant trades men. Family system was patriarchal; women enjoyed a high position in patriarchal society who had liberty to choose their mate. Sindh was a prosperous and fertile country, with flourishing trade. Sindh was abode of various religious groups and sects before the advent of Arabs. On the eve of Arab conquest of Sindh there was rivalry between Hinduism & Buddhism. People of Sindh being unsatisfied by the rule of Brahmans came into contact with Arab invaders and helped them to succeed Brahmans. ____________________ Keywords: Sindh, History, Religions and Social Conditions. INTRODUCTION Sindh is one of the ancient regions of the world. It now forms integral part of Pakistan. ―Sindh or Indus valley proper is a land of great antiquity and claims a civilization anterior in time to that of Egypt and Babylon‖ (Pathan, 1978:46). -

The Story of Sindh, an Economic Survey 1843

The Story of Sindh ( An Economic Survey ) 1843 - 1933 By: Rustom Dinshow Choskey Edited with additional notes by K. Shripaty Sastry Lecturer in History University of Poona The Publication of the Manuscript was financially supported by the Indian Council of Historical Research and the responsibility for the facts stated, opinions expressed or conclusion reached is entirely that of the author and the Indian Council of Historical Research accepts no responsibility for them. Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2015) TO FATIMA in Grateful Acknowledgement For all you have done for me ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our heartfelt thanks are due to the members of the Choksey family for kindly extending their permission to publish this book. Mr. D. K. Malegamvala, Director and Mr. R. M Lala Executive Officer of The Sir Dorab Tata Trust, Bombay, took keen interest in sanctioning a suitable publication grant for this book. Prof. H. D. Moogat, Head, Department of Mathematics, N. Wadia College, Poona was a guide, and advisor throughout when the book went through editing and printing. We are grateful also to the Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi for extending financial support for the publication of this book. Dr. A. R. Kulkarni, Head, Department of History, Poona University was a constant source of inspiration while the book was taking shape. CONTENTS Chapter One - Introduction .. .. .. .. Page - 1 Government and life during the tune of the Mirs – Land revenue and other sources of income - Kinds of seasons, soil and implements - Administration of the districts - Life in the Desert - Advent of the British - Sir Charles Napier in Sindh - His administration, revenue collection, trade, justice etc. -

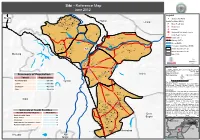

Sibi - Reference Map June 2012

Sibi - Reference Map June 2012 Tor KamanTabai Mustafa Ridge&& Nund Legend Gar & Kaman & Mushkeni && Mushkin Takri Kundak&i & Quetta &Dara & Dik & Khuti Ridge Settlements (NGA) & & & Takri Ridge Wuch Kaman & Garang & Naiju Health Facilities (WHO) Kanobi & Margho Harnai Torag&hari&& ZambroC&hoto Loralai KashmiTakrai && & Daraghar &Shin Kush&tak & & Choto Lath " Gulisti & Bokh &Talan&g u Basic Health Unit Lwar K&halach & Gun Shama & & Gharmob Rud Dailu & Khosun & & Sinjawal Kaman '" Dispensary Taude & River Obo & Kamar j Hospital Tiri Jhal Tarkha Matauri Rasti Garang v® Maternal&Child Health Centre Nala SANGAN Tarkha Nala Garang Nala & Matauri Pasti & Jhal& Lakhi - Rural Health Centre Koh Loe & Guzu'"Sangan Manda '" Dirghi Dungan Ghala Jhal& & & & Roads (WFP) Sar Tor Ghar & & Gamboli Railway (WFP) & Bareli Soi Jhal Barali Nala Soi Sand & KUT Nala & Jhal Angur Kambir Babar Dada Rivers (ESRI) &Angur & & Sangan MANDAI Char Kachhi River Miri Sherani & Khwar & Mushken & & Babar Kach River '" Permanent InlandWater (ESRI) Bulan Siphal Babar & Pass Ridge Kachh Quat Mandai Bijrani & Sehpal & & & Zai & Tehsils boundary (PCO) Tillu Mirdad River '" & Bolan Gwanden Sibi & &Barg & Pass Gwanden Nalani Pishi River Nigaur Samandu & & District boundary (PCO) Nigaur Nala Lar Zardoz Gidari Jhal & & & River Mastung Khajjak & Sibi (PCO) Panni Rud & & SIBI Jaro Torchur Luni River River u"& & & - Gozi Pazh Khajjak River Bakhrua"& Kurak & & Wah '"v® Dehpal & Khajak Branch Kurk &u"& Dehpal Kurak'"& u" Dehpel j u" Ib®is & Sibi v® v®v'" -Talli Map Doc Name: j'" v®