THE OPEN BOAT: Across the Pacific the OPEN BOAT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grace” Owned and Built by Grahame Harris Finished 2015, a TREAD LIGHTLY Design by John Welsford

1. “Grace” Owned and built by Grahame Harris finished 2015, a TREAD LIGHTLY design by John Welsford. Built over a 3 year period from Meranti ply - fibreglassed over (up to the 2nd chine). The original 14ft design has been 'stretched’ to just under 17ft and she carries approx. 230 litres of water ballast. Grace flies a 4 sided “balanced lugsail” of approx 130 sq ft, has twin skegs and twin rudders. She has a 15hp Yamaha outboard mounted in the cockpit. Her name Grace, is a play on the design name “Tread Lightly” 2 ½ years to build in the shed. Carbon fibre 2 pce mast, 6hp 4 stroke outboard in motor well. Sleeps 2 comfortably. Full of BURNSCO accessories - from my work. 2. “Jameelah” Owned by Peter and Raewyn Dunlop. Built in 1994 by Honnor Marine, Devon, UK. Designed by Drascombe Lugger. 5.72m yacht. bought in 2005 from a friend when they lived in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates and on relocating to New Zealand brought her along with them. The name “Jameelah” is an Arabic word used when describing a beautiful woman which we think is very appropriate. The design is based on the original coastal fishing boats of north east England. The mizzen mast and tan sails giving her a traditional look and excellent all weather sailing qualities. She has a GRP hull and deck finished with hard wood trim. The mast is varnished timber and her rig design is “sliding gunter” which allows the top part of the mast to be easily lowered when at anchor or negotiating low structures. -

Article Mercury

Article du journal The Mercury Samedi 21 décembre 1968 HOBART FRENCH SOLO YACHTSMAN OFF BRUNY IS Mail from lone sailor LONE round-the-world sailor Bernard Moitessier made his first contact with teh outside world for at least eight weeks when he signalled a fisherman in Tasmanian waters on Wednesday morning. Moitessier (43), a Frenchman, was last reported just south of Capetown in his 42ft steel ketch Joshua. News of his contact with Snug fisherman Varley Wisby became known yesterday. Wisby, who was out fishing on Wednesday morning with his sons, Ross(20) and Robin(17) reported: • he spotted Moitessier's yacht about half way between Cape Bruny Light and Actaeon Island, about 50 miles south west of Hobart. • Moitessier signaled him to within about 12ft and threw him a “mail-box”. • The Frenchman asked about the weather, enjoyed a chat, and went on his way. Messages delivered Moitessier is chasing hard after Britain's Robin Knox-Johnston, leader of the $10,714 “Sunday Times” single-handed round-the- world yacht race. He has not been allowed to take on fuel, food or water since he left Plymouth four months ago. Yesterday, when Wisby delivered Moitessier's mail and messages to the Commodore of Tasmania (Mr J.M.Hickman) he said the yachtsman “looked in high spirits and good health”. Mr Wisby (40) was on a six-day fishing trip in his 42 ft fishing boat, Spring Bay. “It was about 6 am.”, he said. “We were about four or five miles away when we sighted the yacht. “The yacht looked as though it had stopped and was signaling to us with an aldis lamp.” he said. -

(TO HATE) YOU Talking Gays & God with the Comedian

Memoirs Tackle Gays I told (my eighth “grade students) And Christianity nobody should have hate like that for Movies For Everyone each other. On Your Xmas List - Sue Johnson, ”South Lyon teacher LISA LAMPANELLI LOVES (TO HATE) YOU Talking Gays & God With The Comedian NOV 1, 2012 | VOL. 2044 | FREE WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM DEC 6, 2012 | VOL. 2049 | FREE COVER STORY 20 Lisa Lampanelli loves I was asking a lot of questions and in (to hate) you the process I discovered two things I told (my eighth Memoirs Tackle Gays “grade students) nobody should have almost simultaneously: I was And Christianity hate like that for queer each other. Movies For Everyone - Sue Johnson, South” Lyon teacher On Your Xmas List and my church would kick me out if LISA LAMPANELLI they discovered my secret. LOVES (TO HATE) – Chris Stedman, author of "Faitheist: YOU “ How an Atheist Found Common Talking Gays & God With The Comedian Ground with the Religious." Pg. 14 NOV 1, 2012 | VOL. 2044 | FREE DEC 6, 2012 | VOL. 2049 | FREE WWW.PRIDESOURCE.COM NEWS 4 In the welcoming business BTL ISSUE 20.49 • DEC. 6, 2012 5 Ferndale Pride gives $10,000 to ” local charities 6 OU students rally for gender neutral restrooms Join The Conversation @ PrideSource.com 7 South Lyon teacher suspended 10 Marriage debate shifts to US YELLOW PAGES FACEBOOK Supreme Court 11 Ban on gay ‘reparative therapy’ 12 VCU coach says he was fired for being gay 12 Appeal vowed in Nevada same- sex marriage ruling 14 New memoirs tackle complex relationship of gays and Christians Purchasing With Power Help Us Reach 4,500 Fans This holiday season, shop LGBT Every day, BTL reaches OPINION with the Pride Source Yellow thousands of LGBT Michiganders 8 Viewpoint Pages, available online and in with relevant information and 9 Parting Glances print! resources on our Facebook page. -

AMERICAN SOCIETY of MARINE ARTISTS Véçàxçàá 501(C)3 Organization

THE AMERICAN SOCIETYOF MARINE ARTISTS News& Journal VolumeXLII Summer2020 HOLLY BIRD A Printmaker's Voyage ofDiscovery THE 18TH NATIONAL EXHIBITION MARY PETTIS The State ofthe Art Shines at premiereOn Life, Art and Inland Waters BEYOND OUR WALLS Marine Artists We've Noticed VITA:CHARLES RASKOB ROBINSON Leader, Artist and Adventurer 3RD NATIONAL MARINE ARTS CONFERENCE The Society Comes Together to Learn, Grow & Share 1 Constantin Brancusi (1876- 1957), 'Fish' 1924, brass andsteel, 6x 20 inches Upcoming June - July, 2020 18thNational, RevisedSchedule * Jamestown Settlement March-December 2020 GulfQuest Maritime Museum NowonlineonlyFall2020 Burroughs-Chapin Museum ofArt in Myrtle Beach, SC January-April 2021 Minnesota Marine Art Museum June-September2021 Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum Fall 2021 (*dates maychange due to Covid-19 relateddelays andclosures) June 16-20, 2021 4th National Marine Art Conference Join us for presentations by the country’s top marine artists, writers and scholars at the fourth National Marine Art Conference in beautiful Winona, Minnesota, as well as the Opening Reception ofthe 18th National Exhibition at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum, a world-class museum. We are optimistic for a healthy summer in 2021 and will take whatever steps and precautions are necessary to provide a safe and enjoyable event. Look for more information to come, but please mark your calendar. 2 THE AMERICAN SOCIETYOF MARINEARTISTS News&Journal VolumeXLII Summer 2020 Published Quarterlyby THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MARINE ARTISTS VÉÇàxÇàá 501(c)3 Organization NicolasFox, Editor &Layout OUTSIDE THE GARDEN WALLS 5 LenTantillo, Design There are many gifted marine artists out there. It's time we get to know some ofthem. -

Wisconsin Morgan Horse Club Newsletter

Wisconsin Morgan Horse Club Newsletter AMHA 2013 Club of the Year December 2014 Affiliated with the Wisconsin State Horse Council and The American Morgan Horse Association WMHC is raising funds to make a donation to the Ackermann family for Sue’s continuing care/rehab. Judy Tate, 2015 treasurer, will be responsible for the collection. We hope to continue to receive donations until Sarah’s fund raiser this winter. HOLIDAY BRUNCH and JOLLY CHRISTMAS PARTY Lauraine Smith is already busy planning for next year’s Horse Fair. As SUNDAY DECEMBER 14TH 11 AM always,this is a major undertaking on the part of this club and its members. at the Fox and Hounds Information on how to nominate your horse to participate is on pp. 12~13 1298 Friess Lake Rd, Hubertus, WI (262) 628-1111 foxandhoundsrestaurant.com Don’t know who Dundee was? The cost is $21 for adults and $18.50 for Find out pp. 14~15 seniors. That includes beverage, tip & tax. Carol needs to collect the money at the onset. Please RSVP to Carol Pasbrig promptly Find the revised membership form for [email protected] (262)-593-5612 2015 on pages 16 & 17 - and use it! Once again you can list all your horses at no additional cost - which makes a In the spirit of the season, please bring an item/items permanent the record of Morgans in for donation to a food pantry. Also good chance to make a contribution to the fund for Sue Ackermann’s ! Wisconsin. Your horses will be proud to continued care. -

To Download the PDF File

Vi • 1n• tudents like CS; • SIC, pool, city / By Gloria Pena rate, gymnastics, volleyball, , Have you noticed five new stu- r pingpong, stamp collecting, mo I '• dents roamang the halls within del airplane, playing the flute B the last three weeks? Well, they and guitar, and all seemed to be were not here permanently, but enthusiastic about girls were exchange students from Guatemala, Central America, The school here is different vasatang Shreveport, The Louisi from those in Guatemala in the ana Jaycees sponsored these way that here the students go to students and the people they are the classes, where as in Guate staying with will in turn visit mala, the teachers change class Guatamala and stay with a famaly rooms. One sa ad that ·'here the there. students are for the teachers, Whale visitang Shreveport they where there, the teachers are for -did such !hangs as visit a farm in the students." Three of the stu ~aptain ~'trrur 11igtp ..ctpool Texas, where they had a wiener dents are still in high school, roast ; visit Barksdale A ir Force while the other two are in col Base· take an excursion to lege, one studying Architecture Shreve Square, go to parties; and the other studying Business Volume IX Shreveport, La., December 15, 1975 Number 5 take in sO'me skating; and one Administration. even had the experaence of going flying with Mrs. Helen Wray. The students also went shop ping at Southpark Mall of which Christmas brings gifts; they were totally amazed, and at Eastgate Shopping Center by Captain Shreve. One even catalogue offers I aug hs splurged and bought $30 worth By Sandra Braswell $2,250,000. -

Sailing a Dabber Owning a Drifter Tim Severin

DDRASCOMBEA ASSOCIATIONN NEWS www.drascombe-association.org.uk DDRASCOMBEA ASSOCIATIONN NEWS No. 136 • Spring 2021 Sailing a Dabber Owning a Drifter Tim Severin SAMPLE EDITION Netherlands Ireland Italy Association Business Association Business The Association Shop Association Items Drascombe Association News Spring 2021 • No.136 The magazine of the Drascombe Owners’ Association Do you have an article for DAN? Car Sticker Please read this first! Contents Badge Boat Sticker Burgee Cloth Badge We love receiving your articles and would appreciate your Association Business help in getting them printed in DAN. Just follow these simple rules: Who’s Who 4 Chaiman’s Log 4 Length – try to keep to 1500 words; but we can split New Members 5 longer artlicles over two issues. Editor 6 Rally Programme 7 Tie Tea Towel Format – Unformatted Word Document (not pdf or typed onto an email, each of which require retyping or Rally Form 10 Mugs Knitted Beanie reformatting). Photo Competition 12 Committee News 13 Burgee Tan Lugger on cream, supplied with toggle and eye £15.50 Photos – please: Drascombe Mug features the Dabber, Lugger & Coaster. By Bob Heasman £8.00 • Provide captions or explanations; Regular Features Knitted Beanies Navy with Bronze Lugger logo. One size fits all £9.50 • Tell us who took them; News from the Netherlands 14 Lapel Pin Badge Metal enameled Drascombe Lugger £4.00 • Send as separate, high resolution, jpg files; Tim Severin - Obituary 15 Drascombe Car Sticker “Drascombe – the sail that becomes a way of life” £1.50 • Do not send me links to websites – photo quality will Junior DAN 16 Drascombe Boat Sticker. -

Re-Up Brunch Marks Beginning of SCOW Sailing Class Registration

The Newsletter of the Sailing Club of Washington March 2008 Re-Up Brunch Marks Beginning of SCOW Sailing Class Registration Rub-Off-the-Rust, Train-the-Trainers Sessions Set for Late March By Mike Rothenberg 2008 SCOW Training Director The Club’s Re-Up Brunch on Sunday, March 16 marks opening day for registration for SCOW sailing classes. Be sure to attend and get there early, if you want to prepare to become a Flying Scot or Cruiser Skipper by attending the first classes, which begin in April, so you can maximize your enjoyment as a skipper for Spring, Summer and Fall of 2008. The slots for all classes go fast. But, they go even faster for the April Basic Sailing and Cruiser classes. Other popular classes are the Spinnaker and Capsize courses, and don’t forget our Intermediate sailing class, which is returning to an older more inclusive format this year. In the recent past, many of the registrants for the Intermediate Class were Scot skippers, but the class is also for Cruiser skippers as well as crew for both the club’s daysailers and keelboats. Last year the class was limited to 12, but this year capacity will be 18-24 students, depending on the mix of Scot and Cruiser sailors. To see the latest schedule of classes in advance of the Re-Up Brunch, see the SCOW calendar of events online at http://www.scow.org/calendar.html Save Some Money as a Class Coordinator If you’re planning to sign up for a Basic Sailing Class or Cruiser Class and would like to save some money, the Club offers a $50 discount for one lucky person in each class, if they sign up to be the Class Coordinator. -

FF 2020-1 Pages + Covers @ A4.Indd

22020/1020/1 ® TThehe JJournalournal ooff tthehe OOceancean CCruisingruising ClubClub 1 “I am not afraid of storms for I am learning to sail my ship.” —Louisa May Alcott 2 OCC FOUNDED 1954 offi cers COMMODORE Simon Currin VICE COMMODORES Daria Blackwell Paul Furniss REAR COMMODORES Jenny Crickmore-Thompson Zdenka Griswold REGIONAL REAR COMMODORES GREAT BRITAIN Beth & Bone Bushnell IRELAND Alex Blackwell NORTH WEST EUROPE Hans Hansell NORTH EAST USA Dick & Moira Bentzel SOUTH EAST USA Bill & Lydia Strickland WEST COAST NORTH AMERICA Ian Grant HAWAII, CALIFORNIA & MEXICO Rick Whiting NORTH EAST AUSTRALIA Nick Halsey SOUTH EAST AUSTRALIA Paul & Lynn Furniss SPECIALIST (TECHNICAL) Frank Hatfull ROVING REAR COMMODORES Nicky & Reg Barker, Suzanne & David Chappell, Guy Chester, Andrew Curtain, Fergus Dunipace & Jenevora Swann, Ernie Godshalk, Bill Heaton & Grace Arnison, Alistair Hill, Barry Kennedy, Stuart & Anne Letton, Pam McBrayne & Denis Moonan, Sarah & Phil Tadd, Gareth Thomas, Sue & Andy Warman PAST COMMODORES 1954-1960 Humphrey Barton 1994-1998 Tony Vasey 1960-1968 Tim Heywood 1998-2002 Mike Pocock 1968-1975 Brian Stewart 2002-2006 Alan Taylor 1975-1982 Peter Carter-Ruck 2006-2009 Martin Thomas 1982-1988 John Foot 2009-2012 Bill McLaren 1988-1994 Mary Barton 2012-2016 John Franklin 2016-2019 Anne Hammick SECRETARY Rachelle Turk Westbourne House, 4 Vicarage Hill Dartmouth, Devon TQ6 9EW, UK Tel: (UK) +44 20 7099 2678 Tel: (USA) +1 844 696 4480 e-mail: [email protected] EDITOR, FLYING FISH Anne Hammick Tel: +44 1326 212857 e-mail: [email protected] OCC ADVERTISING Details page 252 OCC WEBSITE www.oceancruisingclub.org 1 CONTENTS PAGE Editorial 3 The 2019 Awards 4 Sailing the South Coast of Newfoundland 27 Jan Steenmeijer From the galley of .. -

Latitude 38 November 2009

NovCoverTemplate 10/16/09 3:04 PM Page 1 Latitude 38 VOLUME 389 November 2009 WE GO WHERE THE WIND BLOWS NOVEMBER 2009 VOLUME 389 We know boaters have many choices when shopping for berthing, and all of us here at Grand Marina want to Thank you for Giving us the opportunity to provide you with the best service available in the Bay Area year after year. • Prime deep water concrete slips in a variety of sizes DIRECTORY of • Great Estuary location at the heart GRAND MARINA of the beautiful Alameda Island TENANTS • Complete bathroom and shower Bay Island Yachts ........................... 8 facility, heated and tiled Blue Pelican Marine ................... 160 The Boat Yard at Grand Marina ... 13 • FREE pump out station open 24/7 Lee Sails ..................................... 156 • Full Service Marine Center and Marine Lube ............................... 163 haul out facility Pacific Crest Canvas ..................... 51 • Free parking Pacific Yacht Imports ..................... 9 510-865-1200 Rooster Sails ................................ 61 Leasing Office Open Daily • Free WiFi on site! UK-Halsey Sailmakers ............... 124 2099 Grand Street, Alameda, CA 94501 And much more… www.grandmarina.com Page 2 • Latitude 38 • November, 2009 ★ Happy Holidays from all of us at Pineapple Sails. We’ll be closed from Carbon Copy Sat., Dec. 19, through Sun., Jan. 3. There are words to describe the design of a good one-design sailboat and one of the best words is “durable.” The Express 37 is just such a boat. Designed by Carl Schumacher in 1984, the class still does a full season of races each year, culminating in St. Francis Yacht Club’s Rolex Big Boat Series. -

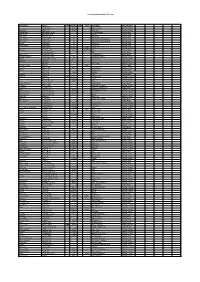

C:\Boatlists\Boatlistdraft-2021.Xlsx Boat Name Owner Prefix Sail No

C:\BoatLists\boatlistdraft-2021.xlsx Boat Name Owner Prefix Sail No. Suffix Hull Boat Type Classification Abraham C 2821 RS Feva XL Sailing Dinghy Dunikolu Adams R 10127 Wayfarer Sailing Dinghy Masie Mary Adlington CPLM 18ft motorboat Motor Boat Isla Rose Adlington JPN Tosher Sailing Boat Demelza Andrew JA 28 Heard 28 Sailing Boat Helen Mary Andrew KC 11 Falmouth Working Boat Sailing Boat Mary Ann Andrew KC 25 Falmouth Working Boat Sailing Boat Verity Andrew N 20 Sunbeam Sailing Boat West Wind Andrew N 21 Tosher 20 Sailing Boat Andrews K 208210 white Laser 4.7 Sailing Dinghy Hermes Armitage AC 70 dark blue Ajax Sailing Boat Armytage CD RIB Motor Boat Alice Rose Ashworth TGH Cockwell's 38 Motor Boat Maggie O'Nare Ashworth TGH 10 Cornish Crabber Sailing Cruiser OMG Ashworth* C & G 221 Laser Pico Sailing Dinghy Alcazar Bailey C Motor Boat Bailey C RS Fevqa Sailing Dinghy Dither of Dart Bailey T white Motor Sailer Coconi Barker CB 6000 Contessa 32 Sailing Cruiser Diana Barker G Rustler 24 Sailing Boat Barker G 1140 RS200 Sailing Dinghy Gemini Barnes E RIB Motor Boat Pelorus Barnes E GBR 3731L Arcona 380 Sailing Cruiser Barnes E 177817 Laser Sailing Dinghy Barnes F & W 1906 29er Sailing Dinghy Lady of Linhay Barnes MJ Catamaran Motor Boat Triumph Barnes MJ Westerly Centaur Sailing Cruiser Longhaul Barstow OG Orkney Longliner 16 Motor Boat Barö Barstow OG 2630 Marieholm IF-Boat Sailing Cruiser Rinse & Spin Bateman MCW 5919 Laser Pico Sailing Dinghy Why Hurry Batty-Smith JR 9312 Mirror Sailing Dinghy Natasha Baylis M Sadler 26 Sailing Cruiser -

1 Sailing Instructions CCSC Pursuit Barnes Cup 2Nd July 2017 1. The

Sailing Instructions CCSC Pursuit Barnes Cup 2nd July 2017 1. The Race will be governed by the Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS). The Start 2. The Start line shall be between the forward mast of the Club Committee Boat and the OLM. 3. Start times for boat classes are given in Appendix A and will be signalled from the Committee boat by displaying numerals 1 to 113. Boats in Classes not indicated in Appendix A must apply to the Sailing Secretary for a start time/ number – email [email protected]. 4. Displaying the number on the start board indicates 1 minute to the start. Start when the number is covered/removed. No sound signal will be made. 5. If a boat is on the course side of the Start Line when the start board is covered/removed, Flag X will be flown for 20 seconds and the boat will be scored OCS unless the boat re starts by returning fully to the pre-start side of the line. No sound signal will be made. 6. A boat may start at any time after it’s Class start time as indicated in Appendix A 7. The course (Trapezoid) will be displayed on the Committee Boat and must be sailed until the Finish. 8. The Start Line is not a mark of the course after the start. (comment: The Committee Boat may remain in position on the course but the OLM will be removed after the last boat starts and boats do not need to cross the start line to complete a ‘lap’ – once started just keep sailing the course until the finish) The Finish 9.