Hood River Were Called Smock-Shops by Lewis and Clark and Generally Lived on the Columbia River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deschutes National Forest

Deschutes National Forest Summer Trail Access and Conditions Update KNOW BEFORE YOU GO! Updated July 13, 2013 Summer Trail Highlights Summer weather, high summer/holiday use at many recreation sites and trails. Remaining snow limited to South Sister, Broken Top, Road 370 and a few patches on trails and the volcanoes above 6,000’ along the Crest. Reports of heavy blowdown (50+ trees/mile) on some trails. Wilderness Permits required. Broken Top TH and 370 Road from Todd Lake to Road 4601 are blocked by snow and closed until determined safe. June 29 photo from Broken Top. Nearly all Wilderness Tumalo Falls road open to vehicle trails are snow free with a few patches likely remaining traffic. North Fork Trail is cleared of along the PCT and on climber trails and routes up the blow down; open to bikers uphill only. volcano peaks. 16 Road and Three Creek Lakes are open and snow free. Tumalo Mt. Trail may yet have a patch or two of snow but very passible. Green Lks/Moraine Lks Trails are snow free with light blowdown. PCT has patchy snow above 6,000’ with some trail clearing in progress. Mosquito populations are highly variable with some backcountry lakes and riparian areas at high levels. Go prepared with your Ten Essential Systems: Navigation (map and compass) Sun protection (sunglasses/sunscreen) Ongoing Suttle Lake trail project with Deschutes NF Trail Insulation (extra clothing) Crew constructing one of many rock retaining walls. For Illumination (headlamp/flashlight) Your safety, please use caution and leash dogs when First-aid supplies approaching trail crews working the various trails on the Fire(waterproofmatches/lighter/candles) Deschutes. -

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project

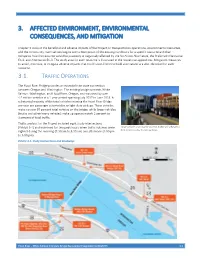

3. AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES, AND MITIGATION Chapter 3 looks at the beneficial and adverse impacts of the Project on transportation operations, environmental resources, and the community. Each section begins with a description of the existing conditions for a specific resource and then compares how the resource would be positively or negatively affected by the No Action Alternative, the Preferred Alternative EC-2, and Alternative EC-3. The study area for each resource is illustrated in the respective appendices. Mitigation measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse impacts that could result from the build alternatives are also identified for each resource. 3.1. TRAFFIC OPERATIONS The Hood River Bridge provides an essential interstate connection between Oregon and Washington. The existing bridge connects White Salmon, Washington, and Hood River, Oregon, and was used by over 4.5 million vehicles in a 1-year period spanning July 2017 to June 2018. A substantial majority of the total vehicles crossing the Hood River Bridge per year are passenger automobiles or light-duty pickups. These vehicles make up over 97 percent total vehicles on the bridge, while larger vehicles (trucks and other heavy vehicles) make up approximately 2 percent to 3 percent of total traffic. Traffic analysis for the Project included eight study intersections (Exhibit 3-1) and examined for two peak hours when traffic volumes were Large vehicles crossing the existing bridge are advised to highest during the morning (7:30 am to 8:30 am) and afternoon (4:00 pm turn in mirrors due to narrow lanes. to 5:00 pm). Exhibit 3-1. -

Hood River – White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project SDEIS

(OR SHPO Case No. 19-0587; WA DAHP Project Tracking Code: 2019-05-03456) Draft Historic Resources Technical Report October 1, 2020 Prepared for: Prepared by: In coordination with: 111 SW Columbia 851 SW Sixth Avenue Suite 1500 Suite 1600 Portland, Oregon 97201 Portland, Oregon 97204 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Project Alternatives ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. No Action Alternative .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Preferred Alternative EC-2 ................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Alternative EC-1 ................................................................................................................ 14 2.4. Alternative EC-3 ................................................................................................................ 19 2.5. Construction of the Build Alternatives ............................................................................... 23 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Newsletter Newsletter of the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Retirees — Fall 2011

OldSmokeys Newsletter Newsletter of the Pacific Northwest Forest Service Retirees — Fall 2011 President’s Message—John Berry It was good to see and talk with so many of you at the Summer Picnic. Some I had not seen for years and I wished there had been more time to catch up. And it was a pleasure to see the great attendance by Regional Office and Mt. Hood National Forest leaders. It means a lot to have Regional Forester and OldSmokey Kent Connaughton and Forest Supervisor Chris Worth attend our functions. Both are very approachable and great listeners. It’s good to see the Region is in good hands. A big thanks to Mike Ash for donating one of his beautiful wood bowls for the raffle to support the PNWFSA Emergency Relief Fund. And, no, I did not bribe Kent Connaughton to draw my wife’s ticket! Thanks to Rick Larson for reserving the picnic area. Thanks to Bev Pratt, Mary Moyer, and Deb Warren for welcoming and doing the name tags. Of course, Dave Dalton and his crew did a great job of catering. Also, check out Paul Enberg’s and John Poppino’s photos on our website at <www.oldsmokeys.org>. The picnic reminds me what it means to be a member of the “Forest Service Family.” Next to my own family, the Forest Service has been the single most important factor in my life. The Forest Service offered me incredible career opportunities as it p rovided outstanding education and training, good pay, and a retirement annuity that allows my wife and me to live comfortably. -

Corridor Plan

HOOD RIVER MT HOOD (OR HIGHWAY 35) Corridor Plan Oregon Department of Transportation DOR An Element of the HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR 35) CORRIDOR PLAN Oregon Department of Transportahon Prepared by: ODOT Region I David Evans and Associates,Inc. Cogan Owens Cogan October 1997 21 October, 1997 STAFF REPORT INTERIM CORRIDOR STRATEGY HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR HWY 35) CORRIDOR PLAN (INCLUDING HWY 281 AND HWY 282) Proposed Action Endorsement of the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor Strategy. The Qregon Bep ent of Transportation (ODOT) has been working wi& Tribal and local governments, transportation service providers, interest groups, statewide agencies and stakeholder committees, and the general public to develop a long-term plan for the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor. The Hood River-Mt. Hood Corridor Plan is a long-range (20-year) program for managing all transportation modes within the Oregon Highway 35 corridor from the 1-84 junction to the US 26 junction (see Corridor Map). The first phase of that process has resulted in the attached Interim Com'dor Stvategy. The Interim Corridor Strategy is a critical element of the Hood River- Mt. Hood Corridor Plan. The Corridor Strategy will guide development of the Corridor Plan and Refinement Plans for specific areas and issues within the corridor. Simultaneous with preparation of the Corridor Plan, Transportation System Plans (TSPs) are being prepared for the cities of Hood River and Cascade Locks and for Hood River County. ODOT is contributing staff and financial resources to these efforts, both to ensure coordination between the TSPs and the Corridor Plan and to avoid duplication of efforts, e.g. -

Geosphere, Published Online on 12 November 2014 As Doi:10.1130/GES00990.1

Geosphere, published online on 12 November 2014 as doi:10.1130/GES00990.1 Geosphere Synchronous late Pleistocene extensional faulting and basaltic volcanism at Four Craters Lava Field, central Oregon, USA Benjamin H. Mackey, Samuel R. Castonguay, Paul J. Wallace and Ray J. Weldon Geosphere published online 12 November 2014; doi: 10.1130/GES00990.1 Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Geosphere Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes Advance online articles have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet appeared in the paper journal (edited, typeset versions may be posted when available prior to final publication). -

The Columbia River Gorge: Its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway by IRA A

VOLUMB 2 NUMBBI3 NOVBMBBR, 1916 . THE .MINERAL · RESOURCES OF OREGON ' PuLhaLed Monthly By The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology Mitchell Point tunnel and viaduct, Columbia River Hi~hway The .. Asenstrasse'' of America The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations Entered aa oeoond cl,... matter at Corvallis, Ore., on Feb. 10, l9lt, accordintt to tbe Act or Auc. :U, 1912. .,.,._ ;t ' OREGON BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY COMMISSION On1cm or THm Co><M188ION AND ExmBIT OREGON BUILDING, PORTLAND, OREGON Orncm or TBm DtBIICTOR CORVALLIS, OREGON .,~ 1 AMDJ WITHY COMBE, Governor HENDY M. PABKB, Director C OMMISSION ABTBUB M. SWARTLEY, Mining Engineer H. N. LAWRill:, Port.land IRA A. WILLIAMS, Geologist W. C. FELLOWS, Sumpter 1. F . REDDY, Grants Pass 1. L. WooD. Albany R. M. BIITT8, Cornucopia P. L. CAI<PBELL, Eugene W 1. KEBR. Corvallis ........ Volume 2 Number 3 ~f. November Issue {...j .· -~ of the MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON Published by The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology ~•, ;: · CONTAINING The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History l Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway t. By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations 1916 ILLUSTRATIONS Mitchell Point t unnel and v iaduct Beacon Rock from Columbia River (photo by Gifford & Prentiss) front cover Highway .. 72 Geologic map of Columbia river gorge. 3 Beacon Rock, near view . ....... 73 East P ortland and Mt. Hood . 1 3 Mt. Hamilton and Table mountain .. 75 Inclined volcanic ejecta, Mt. Tabor. 19 Eagle creek tuff-conglomerate west of Lava cliff along Sandy river. -

Ogv44n10.Pdf

OREGOM GEOLOGY published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries VOLUME44,NUMBER10 OCTOBER 1982 OREGON GEOLOGY OIL AND GAS NEWS (ISSN 0164-3304) Columbia County VOLUME 44, NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 1982 There has been no drilling at the Mist Gas Field since last year. However, Reichhold Energy Corporation, operator of Published monthly by the State of Oregon Department of all nine producing wells at Mist, plans to drill Adams 34-28 in Geology and Mineral Industries (Volumes I through 40 were en titled The Ore Bin). sec. 28, T. 7 N., R. 5 W. The well will be just north of the field boundary and 1 mi from the producer Longview Fibre 12-33. The proposed depth is 3,000 ft, to intersect the already produc Governing Board tive Clark and Wilson sand of the Cowlitz Formation. C. Stanley Rasmussen ........................... Baker Allen P. Stinchfield ........................ North Bend Clatsop County Donald A. Haagensen. .. Portland Work continues on Oregon Natural Gas Development Corporation's Patton 32-9 to sidetrack junk in the hole. A State Geologist . .. Donald A. Hull sand, penetrated by the original hole, will be tested. Deputy State Geologist ..................... John D. Beaulieu Douglas County Editor .. .. Beverly F. Vogt Testing continues on the Florida Exploration Company's 1-4 well near the town of Drain. Three permitted locations re Main Office: 1005 State Office Building, Portland 97201, main for the company in Douglas County. phone (503) 229-5580. Yamhill County Baker Field Office: 2033 First Street, Baker 97814, phone (503) Nahama and Weagant Energy Company of Bakersfield, 523-3133. California, will soon spud Klohs 1 in sec. -

Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6

HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRIIICCC CCCOOOLLLUUUMMMBBBIIIAAA RRRIIIVVVEEERRR HHHIIIGGGHHHWWWAAAYYY OOORRRAAALLL HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRYYY FFFiiinnnaaalll RRReeepppooorrrttt SSSRRR 555000000---222666111 HISTORIC COLUMBIA RIVER HIGHWAY ORAL HISTORY Final Report SR 500-261 by Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator Myra Sperley, ODOT Research Linda Dodds, Historian for Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem OR 97301-5192 August 2009 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. OR-RD-10-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian; Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research; and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns ; Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator; Myra Sperley, ODOT Research; and Linda Dodds, Historian 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 11. Contract or Grant No. 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 SR 500-261 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Oregon Department of Transportation Final Report Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History Project compliments a larger effort in Oregon to reconnect abandoned sections of the Historic Columbia River Highway. -

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Supplemental Draft EIS I

ODOT Key No.: 21280 This page intentionally left blank. This page intentionally left blank. Notice of Document Availability This Supplemental Draft EIS is available for review at the following locations: Port of Hood River (by appointment) 1000 E. Port Marina Drive Hood River, OR 97031 Note: Washington residents can contact the Port to schedule an appointment to view the document in Klickitat County White Salmon Valley Community Library (limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic) 77 NE Wauna Avenue White Salmon, WA 98672 Stevenson Community Library (limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic) 120 NW Vancouver Avenue Stevenson, WA 98648 These documents are also available on the Project website: https://portofhoodriver.com/bridge/bridge-replacement- project/. At the time of publication, Port of Hood River offices are closed due to COVID-19. If you would like to review a hard copy of the Supplemental Draft EIS, please contact the Port at [email protected] or 541-386-1645 to make arrangements for review of the hard copy. The Supplemental Draft EIS can also be viewed at the White Salmon Valley Community Library and the Stevenson Community Library which are open with limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic. How to Submit Comments Written comments on the Supplemental Draft EIS can be submitted during the public comment period (November 20, 2020, through January 4, 2021) by email to [email protected] or regular mail to: Hood River Bridge Supplemental Draft EIS Kevin Greenwood Port of Hood River 1000 E. Port Marina Drive Hood River, OR 97031 Comments can be submitted orally and in writing at the public hearing for the Supplemental Draft EIS on December 3, 2020. -

A Lasting Legacy: the Lewis And

WashingtonHistory.org A LASTING LEGACY The Lewis and Clark Place Names of the Pacific Northwest—Part II By Allen "Doc" Wesselius COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History, Summer 2001: Vol. 15, No. 2 This is the second in a four-part series discussing the history of the Lewis and Clark expedition and the explorers' efforts to identify, for posterity, elements of the Northwest landscape that they encountered on their journey. Columbia River "The Great River of the West" was on the maps that Lewis and Clark brought with them but the cartographic lore of its upper reach influenced William Clark when he identified the supposed upper fork as "Tarcouche Tesse." British explorer Alexander Mackenzie had called the northern reach of the river "Tacoutche Tesse" in his 1793 journals and map. When the explorers realized they had reached the Columbia River on October 16, 1805, they also discerned that they would not discover the source of the drainage, important as that was for establishing the future sovereignty of the region. After Lewis & Clark determined that there was no short portage route between the Missouri and Columbia rivers, the myth of a Northwest Passage evaporated. The priority for the expedition now was to achieve the primary goal of its mission by reaching the mouth of the Columbia River. American rights of discovery to the Columbia were based on Robert Gray's crossing of the bar in 1792 at the river's discharge into the Pacific. He explored the waterway's western bay and named it "Columbia's River" after his ship, Columbia Rediviva. -

The Evolving Landscape of the Columbia River Gorge

The Evolving Landscape of the Columbia River Gorge Jim E. O’Connor Carleton Watkins, photographer, OHS neg., OrHi A reprint from the Oregon Historical Quarterly Special Issue Dissecting the Columbia: Lewis and Clark West of the Divide William L. Lang, guest editor Volume , Number Fall the journal of record for oregon history Jim E. O’Connor The Evolving Landscape of the Columbia River Gorge Lewis and Clark and Cataclysms on the Columbia ravelers retracing lewis and clark’s journey to the Pacific over the past two hundred years have witnessed tre- mendous change to the Columbia River Gorge and its pri- mary feature, the Columbia River. Dams, reservoirs, timber Tharvest, altered fisheries, transportation infrastructure, and growth and shrinkage of communities have transformed the river and valley. This radically different geography of human use and habitation is commonly contrasted with the sometimes romantic view of a prior time provided both by early nineteenth-century chroniclers and present-day critics of the modern condition — an ecotopia of plentiful and perpetual resources sustaining a stable culture from time immemorial. Reality is more com- plicated. Certainly the human-caused changes to the Columbia River and the gorge since Lewis and Clark have been profound; but the geologic his- tory of immense floods, landslides, and volcanic eruptions that occurred before their journey had equally, if not more, acute effects on landscapes and societies of the gorge. In many ways, the Lewis and Clark Expedi- tion can be viewed as a hinge point for the Columbia River, the changes engineered to the river and its valley in the two hundred years since their visit mirrored by tremendous changes geologically engendered in the thousands of years before.