Draft Environmental Impact Statement, Complete

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project

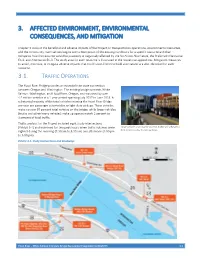

3. AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT, ENVIRONMENTAL CONSEQUENCES, AND MITIGATION Chapter 3 looks at the beneficial and adverse impacts of the Project on transportation operations, environmental resources, and the community. Each section begins with a description of the existing conditions for a specific resource and then compares how the resource would be positively or negatively affected by the No Action Alternative, the Preferred Alternative EC-2, and Alternative EC-3. The study area for each resource is illustrated in the respective appendices. Mitigation measures to avoid, minimize, or mitigate adverse impacts that could result from the build alternatives are also identified for each resource. 3.1. TRAFFIC OPERATIONS The Hood River Bridge provides an essential interstate connection between Oregon and Washington. The existing bridge connects White Salmon, Washington, and Hood River, Oregon, and was used by over 4.5 million vehicles in a 1-year period spanning July 2017 to June 2018. A substantial majority of the total vehicles crossing the Hood River Bridge per year are passenger automobiles or light-duty pickups. These vehicles make up over 97 percent total vehicles on the bridge, while larger vehicles (trucks and other heavy vehicles) make up approximately 2 percent to 3 percent of total traffic. Traffic analysis for the Project included eight study intersections (Exhibit 3-1) and examined for two peak hours when traffic volumes were Large vehicles crossing the existing bridge are advised to highest during the morning (7:30 am to 8:30 am) and afternoon (4:00 pm turn in mirrors due to narrow lanes. to 5:00 pm). Exhibit 3-1. -

State of the System 2016 Report on Oregon's Transportation System

STATE OF THE SYSTEM 2016 REPORT ON OREGON’S TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM OREGON DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION PHOTO CREDITS All photos: ODOT Photo and Video Services or ODOT staff. TABLE OF CONTENTS A INTRODUCTION 2 Transportation System Infrastructure Map 3 An Overview of Oregon’s Transportation System and Why it’s Important for Oregon 3 Purpose of the State of the System Report 3 The Oregon Department of Transportation and its Role in the System 4 Trends Affecting Oregon and its Transportation System 5 The Oregon Transportation Plan and its Implementation 7 The Seven Oregon Transportation Plan Goals B THE STATE OF THE SYSTEM 8 Mobility and Accessibility 14 Management of the System 20 Economic Vitality 28 Sustainability 32 Safety and Security 38 Funding the Transportation System 42 Coordination, Communication and Cooperation C MOVING FORWARD 48 Where to Find Additional Information PAGE 2 STATE OF OREGON State of Oregon TRANSPORTATIONTransportation System SYSTEM Infrastructure INFRASTRUCTURE ? September 2016 Port of Astoria p Port of St. Helens Port of Morrow Port of Umatilla ? Port of Hood River ? Port of Cascade Locks Port of Arlington ? Port of Nehalem ? Port of The Dalles Eastern Oregon THE NUMBERS Port of Portland Regional at Pendleton Portland International ? ? ¨¦§84 ? o ? o ? 73,933 total miles of Port of Garibaldi ? ? highways, streets and Port of Tillamooik Bay roads 8,032 miles of state highways 32,907 miles of county roads ? 11,029 miles of city streets Port of Newport ? Port of Toledo ? 21,965 miles of “other roads” miles of "other -

Hood River – White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Project SDEIS

(OR SHPO Case No. 19-0587; WA DAHP Project Tracking Code: 2019-05-03456) Draft Historic Resources Technical Report October 1, 2020 Prepared for: Prepared by: In coordination with: 111 SW Columbia 851 SW Sixth Avenue Suite 1500 Suite 1600 Portland, Oregon 97201 Portland, Oregon 97204 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Project Alternatives ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. No Action Alternative .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2. Preferred Alternative EC-2 ................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Alternative EC-1 ................................................................................................................ 14 2.4. Alternative EC-3 ................................................................................................................ 19 2.5. Construction of the Build Alternatives ............................................................................... 23 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

Corridor Plan

HOOD RIVER MT HOOD (OR HIGHWAY 35) Corridor Plan Oregon Department of Transportation DOR An Element of the HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR 35) CORRIDOR PLAN Oregon Department of Transportahon Prepared by: ODOT Region I David Evans and Associates,Inc. Cogan Owens Cogan October 1997 21 October, 1997 STAFF REPORT INTERIM CORRIDOR STRATEGY HOOD RIVER-MT. HOOD (OR HWY 35) CORRIDOR PLAN (INCLUDING HWY 281 AND HWY 282) Proposed Action Endorsement of the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor Strategy. The Qregon Bep ent of Transportation (ODOT) has been working wi& Tribal and local governments, transportation service providers, interest groups, statewide agencies and stakeholder committees, and the general public to develop a long-term plan for the Hood River-Mt. Hood (OR HWY 35) Corridor. The Hood River-Mt. Hood Corridor Plan is a long-range (20-year) program for managing all transportation modes within the Oregon Highway 35 corridor from the 1-84 junction to the US 26 junction (see Corridor Map). The first phase of that process has resulted in the attached Interim Com'dor Stvategy. The Interim Corridor Strategy is a critical element of the Hood River- Mt. Hood Corridor Plan. The Corridor Strategy will guide development of the Corridor Plan and Refinement Plans for specific areas and issues within the corridor. Simultaneous with preparation of the Corridor Plan, Transportation System Plans (TSPs) are being prepared for the cities of Hood River and Cascade Locks and for Hood River County. ODOT is contributing staff and financial resources to these efforts, both to ensure coordination between the TSPs and the Corridor Plan and to avoid duplication of efforts, e.g. -

Grain, Flour and Ships – the Wheat Trade in Portland, Oregon

Grain, Flour and Ships The Wheat Trade in Portland, Oregon Postcard Views of the Oregon Grain Industry, c1900 Prepared for Prosper Portland In Partial Fulfillment of the Centennial Mills Removal Project Under Agreement with the Oregon SHPO and the USACE George Kramer, M.S., HP Sr. Historic Preservation Specialist Heritage Research Associates, Inc. Eugene, Oregon April 2019 GRAIN, FLOUR AND SHIPS: THE WHEAT TRADE IN PORTLAND, OREGON By George Kramer Prepared for Prosper Portland 222 NW Fifth Avenue Portland, OR 97209 Heritage Research Associates, Inc. 1997 Garden Avenue Eugene, Oregon 97403 April 2019 HERITAGE RESEARCH ASSOCIATES REPORT NO. 448 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv List of Tables ........................................................................................................................... v 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2. Historic Overview – Grain and Flour in Portland .............................................................. 4 Growing and Harvesting 4 Transporting Grain to Portland ................................................................................... 6 Exporting from Portland ............................................................................................. 8 Flour Mills ................................................................................................................. -

Transit Ridership Per Capita

Transit Rides Average number of transit rides each year per Oregonian Our strategy Oregon’s transportation system supports the increased ridership throughout Oregon. This • Expand services to better serve state’s quality of life and economy across a Key Performance Measure will assist ODOT low-income Oregonians and students in diversity of geographies and people. Public in assessing the impact of the new funds. grades 9 – 12. transportation is a key piece of the transportation system for those who cannot With more money, transit providers will: About the target or choose not to drive. The demand for • Increase service levels in both urban and The target is an annual goal of 32 rides per public transportation in Oregon is rural areas Oregonian. The goal will need to be re- anticipated to increase as population grows. • Offer more intercity and regional route evaluated in two to four years. The target service was set by evaluating transit ridership trends Starting in 2019, an influx of funds from the • Improve transit supports such as and population growth over the five-year Statewide Transportation Improvement improved passenger facilities, and period of 2011 to 2016. Fund (STIF), created as part of the 2017 technologies such as electronic fare and transportation funding package, Keep other integrated fare systems. Oregon Moving, will fund new and expanded • Procure low- and no-emission vehicles. public transportation service, resulting in Facts • 18.9% of households report having a person who regularly uses transit (at least once a week) • 5.0% of workers report normally using transit to get to work * • 4.6% of students report normally using transit to get to school & to work September 2019 Transit Rides, cont. -

ALL COSTS CONSIDERED III — LERC Report on Contracting

All Costs Considered III: Further Analysis on the Contracting Out of School Support Services in Oregon Gordon Lafer, PhD Bob Bussel, PhD Jaxon Love, MBA Labor Education and Research Center University of Oregon February 2013 Acknowledgement The authors wish to thank the Oregon School Employees Association for providing financial assistance for this report. Table of Contents Introduction . 7 “A Big Impact on Longtime Employees” . 9 Assessing Privatization in Central Point . 17 Conclusion . 55 Appendix: Sources . 57 Introduction to “All Costs Considered III: Further Analysis on the Contracting Out of School Support Services in Oregon” ll Costs Considered III” marks employees working under private an extension of two previous contractors. studies conducted by the Labor “A Education and Research Center Since our previous research in (LERC) that examined the 2004 and 2008, several important transfer of school support services developments have occurred (transportation, custodial, food that have influenced the focus of service) to private operation in the this new study. During its 2009 state of Oregon. In our ongoing session, the Oregon Legislature analysis of contracting out (also passed a law (ORS 279B) known as “privatization”), we requiring that public agencies have been guided by a similar conduct a rigorous cost-benefit set of questions. Does the analysis before they decide to shift from public to private contract out a given service. The management actually deliver law stipulates that budgetary promised or predicted savings savings resulting from this to school districts? What is the administrative transfer cannot This study is an personal impact of contracting come solely from reduced wages extension of two out on workers who provide and benefits for workers employed previous studies school support services, and by a public entity. -

Government Camp Summit Rest Area Redevelopment Assessment Report Oregon Solutions | January 2021

Government Camp Summit Rest Area Redevelopment Assessment Report Oregon Solutions | January 2021 Oregon Solutions | January 25, 2021 1 Acknowledgements Oregon Solutions greatly appreciates all those who generously gave their time to inform this assessment and report. Authors Karmen Fore, Director, Oregon Solutions Doug Decker, consultant to Oregon Solutions Contact Oregon Solutions National Policy Consensus Center Hatfield School of Government Portland State University Urban Center, Room 720 506 SW Mill Street Portland, OR 97207-0751 (503) 725-9077, [email protected] www.orsolutions.org Editing and layout: Cat McGinnis, National Policy Consensus Center Cover photo: Mount Hood, Oregon, IStock Oregon Solutions | January 25, 2021 2 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................ 4 2. METHODS ............................................................................................................................................................ 5 3. OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. ASSESSMENT FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................ 6 4.1. High level of alignment and interest ................................................................................................ 6 4.2. Project lead -

Transportation Resource Guide

PORTLAND TRANSPORTATION RESOURCE GUIDE A guide for getting around Portland ST_Transportation_Resource_Guide_2018_0223.indd 1 2/23/18 3:57 PM Table of Contents Walking 1 MAPS AND INFORMATION COMMUNITY WALKS AND HIKES Bicycling 3 MAPS AND INFORMATION COMMUNITY RIDES AND CLINICS BICYCLE RENTALS BICYCLE RIDES AND CLINICS AT A GLANCE Transit 8 Mobility Devices and Accessibility 8 Motorcycles and Motor Scooters 10 Skates and Skateboards 10 Taxis and Pedicabs 10 Sharing 10 BIKE SHARING RIDE SHARING CAR SHARING Getting Out of Portland ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 11 General Transportation Resources ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 13 Important City of Portland Numbers ���������������������������������������������������Back Cover Women-specific rides and clinics offered TABLE OF CONTENTS ST_Transportation_Resource_Guide_2018_0223.indd 2 2/23/18 3:57 PM Walking — Maps and Information City of Portland Active Transportation and Safety Division Walking maps, summer guided walks, safety information, resources, policies and more. portlandoregongov/transportation/at -

Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6

HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRIIICCC CCCOOOLLLUUUMMMBBBIIIAAA RRRIIIVVVEEERRR HHHIIIGGGHHHWWWAAAYYY OOORRRAAALLL HHHIIISSSTTTOOORRRYYY FFFiiinnnaaalll RRReeepppooorrrttt SSSRRR 555000000---222666111 HISTORIC COLUMBIA RIVER HIGHWAY ORAL HISTORY Final Report SR 500-261 by Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator Myra Sperley, ODOT Research Linda Dodds, Historian for Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem OR 97301-5192 August 2009 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. OR-RD-10-03 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History August 2009 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Robert W. Hadlow, Ph.D., ODOT Senior Historian; Amanda Joy Pietz, ODOT Research; and Hannah Kullberg and Sara Morrissey, ODOT Interns ; Kristen Stallman, ODOT Scenic Area Coordinator; Myra Sperley, ODOT Research; and Linda Dodds, Historian 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Oregon Department of Transportation Research Section 11. Contract or Grant No. 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 SR 500-261 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Oregon Department of Transportation Final Report Research Section 200 Hawthorne Ave. SE, Suite B-240 Salem, OR 97301-5192 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The Historic Columbia River Highway: Oral History Project compliments a larger effort in Oregon to reconnect abandoned sections of the Historic Columbia River Highway. -

Polallie Creek Debris Flow and Subsequent Dam-Break Flood of 1980, East Fork Hood River Basin, Oregon

Polallie Creek Debris Flow and Subsequent Dam-Break Flood of 1980, East Fork Hood River Basin, Oregon United States Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2273 Aerial view southwestward up Polallie Creek to Mount Hood. Confluence with the East Fork Hood River visible at lower center. Photograph courtesy of U.S. Forest Service, Mount Hood National Forest, 1971 (L20805-105). POLALLIE CREEK DEBRIS FLOW AND SUBSEQUENT DAM-BREAK FLOOD OF 1980, EAST FORK HOOD RIVER BASIN, OREGON Polallie Creek Debris Flow and Subsequent Dam-Break Flood of 1980, East Fork Hood River Basin, Oregon By GARY L GALLING and THOMAS C. PIERSON U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 2273 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL HODEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE : 1985 For sale by the Distribution Branch, Text Products Section U.S. Geological Survey 604 South Pickett St. Alexandria, VA 22304 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Gallino, Gary L. Polallie Creek debris flow and subsequent dam-break flood of 1980, East Fork Hood River basin, Oregon. (U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2273) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.13:2273 1. Mass-wasting Oregon Polallie Creek Valley. 2. Hood River, East Fork (Or.) Flood, 1980. 3 Floods Oregon Hood River, East Fork Mathematical models. 4. Dam failures Oregon Hood River, East Fork Data processing. 5. Dam failures Oregon Hood River, East Fork Mathematical models. I. Pierson, Thomas C. II. Title. III. Series: U.S. Geological Survey Water- Supply Paper 2273. Qe598.5.U6G351985 363.3'492 84-600368 CONTENTS Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Geographic and hydrologic setting 1 The storm 5 The debris flow 7 What are debris flows 7 Polallie Creek debris flow 7 Flow velocity and discharge 9 Expected basin runoff 11 Erosion and deposition 13 The dam-break flood 15 Impacts 19 Conclusions 20 Acknowledgments 21 References 21 FRONTISPIECE Aerial photograph showing view up Polallie Creek to Mount Hood. -

White Salmon Interstate Bridge Replacement Supplemental Draft EIS I

ODOT Key No.: 21280 This page intentionally left blank. This page intentionally left blank. Notice of Document Availability This Supplemental Draft EIS is available for review at the following locations: Port of Hood River (by appointment) 1000 E. Port Marina Drive Hood River, OR 97031 Note: Washington residents can contact the Port to schedule an appointment to view the document in Klickitat County White Salmon Valley Community Library (limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic) 77 NE Wauna Avenue White Salmon, WA 98672 Stevenson Community Library (limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic) 120 NW Vancouver Avenue Stevenson, WA 98648 These documents are also available on the Project website: https://portofhoodriver.com/bridge/bridge-replacement- project/. At the time of publication, Port of Hood River offices are closed due to COVID-19. If you would like to review a hard copy of the Supplemental Draft EIS, please contact the Port at [email protected] or 541-386-1645 to make arrangements for review of the hard copy. The Supplemental Draft EIS can also be viewed at the White Salmon Valley Community Library and the Stevenson Community Library which are open with limited services during the COVID-19 pandemic. How to Submit Comments Written comments on the Supplemental Draft EIS can be submitted during the public comment period (November 20, 2020, through January 4, 2021) by email to [email protected] or regular mail to: Hood River Bridge Supplemental Draft EIS Kevin Greenwood Port of Hood River 1000 E. Port Marina Drive Hood River, OR 97031 Comments can be submitted orally and in writing at the public hearing for the Supplemental Draft EIS on December 3, 2020.