In Search of the Real Pandolfi: a Musical Journey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jouer Bach À La Harpe Moderne Proposition D’Une Méthode De Transcription De La Musique Pour Luth De Johann Sebastian Bach

JOUER BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE PROPOSITION D’UNE MÉTHODE DE TRANSCRIPTION DE LA MUSIQUE POUR LUTH DE JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH MARIE CHABBEY MARA GALASSI LETIZIA BELMONDO 2020 https://doi.org/10.26039/XA8B-YJ76. 1. PRÉAMBULE ............................................................................................. 3 2. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 3. TRANSCRIRE BACH À LA HARPE MODERNE, UN DÉFI DE TAILLE ................ 9 3.1 TRANSCRIRE OU ARRANGER ? PRÉCISIONS TERMINOLOGIQUES ....................................... 9 3.2 BACH TRANSCRIPTEUR ................................................................................................... 11 3.3 LA TRANSCRIPTION À LA HARPE ; UNE PRATIQUE SÉCULAIRE ......................................... 13 3.4 REPÈRES HISTORIQUES SUR LA TRANSCRIPTION ET LA RÉCEPTION DES ŒUVRES DE BACH AU FIL DES SIÈCLES ....................................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Différences d’attitudes vis-à-vis de l’original ............................................................. 15 3.4.2 La musique de J.S. Bach à la harpe ............................................................................ 19 3.5 LES HARPES AU TEMPS DE J.S. BACH ............................................................................. 21 3.5.1 Panorama des harpes présentes en Allemagne. ......................................................... 21 4. CHOIX DE LA PIECE EN VUE D’UNE TRANSCRIPTION ............................... -

HOWARD COLLEGE MUSIC FALL 2018 RECITAL Monday November 5, 2018 Hall Center for the Arts Linda Lindell, Accompanist

HOWARD COLLEGE MUSIC FALL 2018 RECITAL Monday November 5, 2018 Hall Center for the Arts Linda Lindell, Accompanist Makinsey Grant . Bb Clarinet Fantasy Piece No. 1 by Robert Schumann Fantasy Piece No. 1 by Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856) was written in 1849. It is the first movement of three pieces written to promote the creative notion of the performer. It allows the performer to be unrestricted with their imagination. Fantasy Piece No. 1 is written to be “Zart und mit Ausdruck” which translates to tenderly and expressively. It begins in the key of A minor to give the audience the sense of melancholy then ends in the key of A major to give resolution and leave the audience looking forward to the next movements. (M. Grant) Tony Lozano . Guitar Tu Lo Sai by Giuseppe Torelli (1650 – 1703) Tu lo sai (You Know It) This musical piece is emotionally fueled. Told from the perspective of someone who has confessed their love for someone only to find that they no longer feel the same way. The piece also ends on a sad note, when they find that they don’t feel the same way. “How much I do love you. Ah, cruel heart how well you know.” (T. Lozano) Ruth Sorenson . Mezzo Soprano Sure on this Shining Night by Samuel Barber Samuel Barber (1910 – 1981) was an American composer known for his choral, orchestral, and opera works. He was also well known for his adaptation of poetry into choral and vocal music. Considered to be one of the composers most famous pieces, “Sure on this shining night,” became one of the most frequently programmed songs in both the United States and Europe. -

Ars Lyrica Houston Announces 2018/19 Season: out of the Box: Celebrating Ambition & Innovation

4807 San Felipe Street, Suite #202 PRESS RELEASE Houston, TX 77056 Media Contact Tel: 713-622-7443 Shannon Langman Tickets: 713-315-2525 Ars Lyrica Houston arslyricahouston.org Marketing & Office Manager [email protected] Matthew Dirst 713-622-7443 Artistic Director Kinga Ferguson Executive Director Ars Lyrica Houston Announces 2018/19 Season: Out of the Box: Celebrating Ambition & Innovation Houston, April 7, 2018 – Ars Lyrica Houston, the Grammy nominated early music ensemble, announces its 2018/19 season: Out of the Box: Celebrating Ambition & Innovation. Ars Lyrica Houston takes on its first full- length Baroque opera with Handel’s Agrippina plus the complete “Brandenburg” Concertos by J. S. Bach. Artistic Director Matthew Dirst has created a program “that highlights composers and works that are exceptional, definitive, unusual, even infamous.” With Bach’s six concertos appearing in pairs throughout the season, individual programs explore distinct ways of thinking about the general theme, from unexpected musical gifts to singular collections and composers. Re-Gifting with Royalty opens the season on Friday, September 21st and includes works of leading composers of the Baroque era who often repurposed their own works, especially when a royal patron needed a special gift. Bach’s “Six Concertos for Diverse Instruments” (as he titled them) were assembled, not composed afresh, for the Margrave of Brandenburg, while Couperin collected his chamber music at regular intervals for the royal seal of approval from Louis XIV. The fifth and sixth “Brandenburg” concertos turned the genre on its head, with an unprecedented harpsichord cadenza (in No. 5) and a violin-free texture of lower strings only (in No. -

17CM Fall 2011.Indd

The Newsletter of the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music Vol. 21,20, No. 1,3, Fall 2011 Seventeenth-Century“Manhattan” for SSCM Music 201 in2 byIndianapolis: Barbara Hanning Notes from AMS 2010 by Brians Oberlanderthe old Rodgers and Hart song proclaims,he American the Musicological island of Manhat Society- careful analysis of the extant score of Akheldtan holdsits 2010 an Annualembarrassment Meeting inof Artemisia, tracing a certain expressive logic riches todowntown delight Indianapolismembers of (November the Soci- in the composer’s revisions and placing this Tety for Seventeenth-Century Music for 4–7), joined by the Society for Music Theory. in dialogue with such theoretical sources Paperstheir twentieth relevant toannual seventeenth-century conference, to as Aristotle and Descartes. In another musicbe held were April delightfully 19–22, 2012, numerous at the Metand- venture of revaluation, Valeria De Lucca generallyropolitan Museumof fine quality, of Art thoughin New York.most argued against the idea of an operatic nadir Home to 1.5 million people, New York were found in sessions that looked beyond in Rome following the closure of its first County (Manhattan) is still neverthe- periodization. From “Special Voices” and Venetian-style theater in 1675. Presenting less a clutch of small neighborhoods, “Marianeach with Topics” its distinct to “Private style Musics”and flavor. and a detailed case study of Prince Lorenzo “Beyond the Book,” the seventeenth century Colonna and his semi-private enterprise The song will serve to highlight some as “Museum Mile,” which includes Park. The concert, on Saturday took its place alongside studies of the met- at the Colonna palace, De Lucca revealed of those relevant to the conference. -

Reappraising the Seicento

Reappraising the Seicento Reappraising the Seicento: Composition, Dissemination, Assimilation Edited by Andrew J. Cheetham, Joseph Knowles and Jonathan P. Wainwright Reappraising the Seicento: Composition, Dissemination, Assimilation, Edited by Andrew J. Cheetham, Joseph Knowles and Jonathan P. Wainwright This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Andrew J. Cheetham, Joseph Knowles, Jonathan P. Wainwright and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5529-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5529-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Examples and Tables ..................................................................... vii Library Sigla and Pitch Notation ................................................................ xi Abbreviations ........................................................................................... xiii Foreword ................................................................................................... xv Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Joseph Knowles and Andrew J. Cheetham Chapter -

14 May 2021.Pdf

14 May 2021 12:01 AM Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) Overture to "Il Barbiere di Siviglia" KBS Symphony Orchestra, Chi-Yong Chung (conductor) KRKBS 12:09 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Geistliches Wiegenlied Op 91 no 2 Judita Leitaite (mezzo soprano), Arunas Statkus (viola), Andrius Vasiliauskas (piano) LTLR 12:15 AM John Dowland (1563-1626),Thomas Morley (1557/58-1602) Morley: Fantasie; Dowland: Pavan; Earl of Derby, his Galliard Nigel North (lute) GBBBC 12:25 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Concerto for 4 keyboards in A minor (BWV.1065) Ton Koopman (harpsichord), Tini Mathot (harpsichord), Patrizia Marisaldi (harpsichord), Elina Mustonen (harpsichord), Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra, Ton Koopman (director) DEWDR 12:35 AM Victor Herbert (1859-1924) Moonbeams - a serenade from the 1906 operetta 'The Red Mill' Symphony Nova Scotia, Boris Brott (conductor) CACBC 12:39 AM Gabriel Faure (1845-1924) Cello Sonata no 2 in G minor, Op 117 Torleif Thedeen (cello), Roland Pontinen (piano) DKDR 12:58 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Symphony no 38 in C major, H.1.38 Danish Radio Sinfonietta, Rinaldo Alessandrini (conductor) DKDR 01:17 AM Alessandro Stradella (1639-1682) Quando mai vi Stancherete Emma Kirkby (soprano), Alan Wilson (harpsichord) DEWDR 01:25 AM Adrian Willaert (c.1490-1562) Pater Noster Netherlands Chamber Choir, Paul van Nevel (conductor) NLNOS 01:29 AM Robert Schumann (1810-1856) 7 Klavierstucke in Fughettenform Op.126 for piano (nos.5-7) Andreas Staier (piano), Tobias Koch (piano) PLPR 01:38 AM Antonio Rosetti (c.1750-1792) Horn Concerto -

Stradella [Romantic Opera, in Three Acts; Text by Deschamps and Pacini

Stradella [Romantic opera, in three acts; text by Deschamps and Pacini. First produced as a lyric drama at the Palais Royal Theatre, Paris, in 1837; rewritten and produced in its present form, at Hamburg, December 30, 1844.] PERSONAGES. Alessandro Stradella, a famous singer. Bassi, a rich Venetian. Leonora, his ward. Barbarino, } Malvolio, } bandits. [Pupils of Stradella, masqueraders, guards, and people of the Romagna.] The scene is laid in Venice and Rome; time, the year 1769. The story of the opera follows in the main the familiar historical, and probably apochryphal, narrative of the experiences of the Italian musician, Alessandro Stradella, varying from it only in the dénouement. Stradella wins the hand of Leonora, the fair ward of the wealthy Venetian merchant, Bassi, who is also in love with her. They fly to Rome and are married, but in the mean time are pursued by two bravos, Barbarino and Malvolio, who have been employed by Bassi to make way with Stradella. They track him to his house, and while the bridal party are absent, they enter in company with Bassi and conceal themselves. Not being able to accomplish their purpose on this occasion, they secure admission a second time, disguised as pilgrims, and are kindly received by Stradella. In the next scene, while Stradella, Leonora, and the two bravos are singing the praises of their native Italy, pilgrims on their way to the shrine of the Virgin are heard singing outside, and Leonora and Stradella go out to greet them. The bravos are so touched by Stradella's singing that they hesitate in their purpose. -

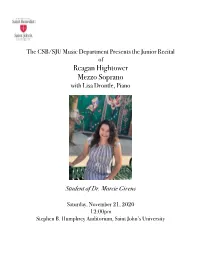

Recital Program Junior

The CSB/SJU Music Department Presents the Junior Recital of Reagan Hightower Mezzo Soprano with Lisa Drontle, Piano Student of Dr. Marcie Givens Saturday, November 21, 2020 12:00pm Stephen B. Humphrey Auditorium, Saint John’s University Program “Volksliedchen” Robert Schumann (1810-1856) “Der Blumenstrauss” Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) “Bist Du Bei Mir” Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) “Dream Valley” Roger Quilter (1877-1953) “Weep You No More, Sad Fountains” John Dowland (1563-1626) “Weep You No More” Roger Quilter (1877-1953) “Pietà, Signore!” Alessandro Stradella (1639-1682) Translations and Texts “Volksliedchen” Wenn ich früh in den Garten geh’ When at dawn I enter the garden, In meinem grünen Hut, Wearing my green hat, Ist mein erster Gedanke, My thoughts first turn Was nun mein Liebster tut? To what my love is doing. Am Himmel steht kein Stern, Every star in the sky Den ich dem Freund nicht gönnte. I’d give to my friend; Mein Herz gäb’ ich ihm gern, I’d willingly give him my very heart, Wenn ich’s heraustun könnte. If I could tear it out. “Der Blumenstrauss” Sie wandelt im Blumengarten She strolls in the flower-garden Und mustert den bunten Flor, and admires the colourful blossom, Und alle die Kleinen warten and all the little blooms are there waiting Und schauen zu ihr empor. and looking upwards towards her. Und seid ihr denn “So you are spring’s messengers, Frühlingsboten, announcing what is always so new – Verkündend was stets so neu, then be also my messengers So werdet auch meine Boten to the man who loves me faithfully.” An ihn, der mich liebt so treu.« So she surveys what she has available So überschaut sie die Habe and arranges a delightful garland; Und ordnet den lieblichen and she gives this gift to her man friend, Strauß, and evades his gaze. -

Handel: Israel in Egypt Performed October 24, 1998

Handel: Israel in Egypt Performed October 24, 1998 It is one of the great ironies of music that the composer who is associated with the greatest choral music in the English language was in fact a German whose lifelong interest was Italian opera. Handel wrote and produced more than forty operas, composed some of the most engaging keyboard and orchestral music of the Baroque period and was one of the great organ virtuosi of all time, yet he is largely remembered for a single musical form, the oratorio, to which he turned only when Italian opera fell out of favor. Early Years George Frideric Handel was born in 1685 in Halle, son of a prominent surgeon at the court of the Duke of Saxony. Handel's father intended a career in law for him, but did allow him to study with Friedrich Zachow, organist at the Liebfraukirche in Halle. Zachow was also a competent composer, well versed in the modern Italian style, and the young Handel was given a firm grounding in composition and theory as well as organ, harpsichord and violin. By the age of thirteen he was already composing cantatas for performance at church and at seventeen was appointed organist at the Domkirche in Halle. In 1703 Handel moved to Hamburg, where he obtained a position as a back desk violinist at the opera. By the next season, at age nineteen, he had become conductor, leading productions from the harpsichord, and had an increasing influence on the artistic direction of the company. It was in Hamburg that he composed his first four operas, two of which were premiered a month apart in 1705. -

Department of Music Programs 1973 - 1974 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 1974 Department of Music Programs 1973 - 1974 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 1973 - 1974" (1974). School of Music: Performance Programs. 7. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROGRAMS 1973-1974 DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC OLIVET NAZARENE COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC presents SENIOR RECITAL D 0 fl R 0 H R E R, t e n o r Marilyn Prior, accompanist cu>6i6te.d by DENNIS BALDRIDGE, TROMBONE Sue Bumpus, accompanist Music for a While Henry Purcell Se tu m'ami Giovanni Pergolesi Che fiero costume ..................... Giovanni Legrenzi Del piu sublime soglio W. A. Mozart M r . Rohrer Meditation ..................... Vladimir Bakaleinikoff A r i a .................................................... Bach Solo De Concours .............. .... Croce-Spinelli Mr. Baldridge Widmung .................................... Robert Schumann Wohin ....................................... Franz Schubert Minnelied ................................. Johannes Brahms Apres un R e v e .............................. Gabriel Faure L'ombre est triste ................ Serge Rachmaninoff M r . Rohrer Apres un R e v e ................................ Gabriel Faure M e n u e t ................................................. Bach Honor and A r m s .......................... Frederick Handel Mr. Baldridge (over) Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal . Roger Quilter Passing By ......................... -

The Rise of Italian Opera & Oratorio

Early Music Hawaii presents The Rise of Italian Opera & Oratorio The Early Music Hawaii Singers and Players Scott Fikse, director The Singers Taylor Ishida, Andrea Maciel, Georgine Stark soprano Naomi Castro, Sarah Lambert Connelly alto Kawaiola Murray, Karol Nowicki, Benjamin Leonid tenor Dylan Bunten, Scott Fikse, Keane Ishii bass The Players Darel Stark, Maile Reeves violin Nancy Welliver recorder James Gochenouer cello Megan Bledsoe Ward harp Katherine Crosier harpsichord, organ Saturday, September 14, 2019 † 7:30 pm Lutheran Church of Honolulu 1730 Punahou Street Program Lamento d’Arianna (1619) Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Sonata per due Violini Biagio Marini (c.1587-1663) L’Incoronazione di Poppea: Claudio Monteverdi Come dolci, Signor, come soavi Naomi Castro, Poppea, Sarah Connelly, Nero Amici, e giunta l’hora Keane Ishii, Seneca Pur ti miro – Poppea & Nero Intermission Dialogo di Lazaro Domenico Mazzocchi (1592-1665) Sinfonia a Tre Alessandro Stradella (1639-1682) Recit & Aria: Nel agone – Su la tela Alessandro Stradella Georgine Stark Christmas Theater: La Caccia del Toro Cristofaro Caresana (c.1640-1709) Dylan Bunten, Toro, Georgine Stark, Humiltà * * * Program Notes The early 17th century marks a dramatic turning point in the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque. Elegant polyphony, in which multiple lines of independent melody were interweaved in a single work, gave way to the freedom of expression offered by a ground bass, instrumental or vocal, as the controlling voice of the harmony, over which soloists could both improvise and explore the emotions. Out of this concept of “melody and bass” arose the essential components of opera, oratorio, cantata and many instrumental forms such as the sonata. -

Recording Reviews

Recording reviews David R. M. Irving others, accompanied by a lively continuo group contain- ing harp, theorbo, viol, and harpsichord or organ. I have Italian (and related) instrumental to admit that I was not quite sure what to expect when I first put this disc in the player; however, I was quickly music of the 17th century won over by the astounding virtuosity of Adam Woolf in executing so deftly and cleanly the sorts of fast diminu- The recordings reviewed here present a whole panoply tions that challenge players of treble instruments such as of repertory, styles, genres and instrumentations from violin and recorder, and by the sheer beauty of his per- the Italian seicento (as well as Italian-inspired tradi- formance in the slower works. It was wonderful also to tions). From violin sonatas accompanied by one plucked hear the assured and rhetorical playing of keyboardist instrument to ensembles with a veritable menagerie of Kathryn Cok—especially on the organ, which she really continuo instruments—and from strict interpretations makes speak. The other members of the continuo ensem- Downloaded from of notation to improvised inventions—we can hear that ble (Siobhán Armstrong on harp, Nicholas Milne on viol early Italian instrumental music provides endless inspira- and Eligio Luis Quinteiro on theorbo) do a splendid job tion for performers and audiences alike. Although many in accompanying an instrument that they would rarely discs reviewed here come from the familiar world (for this support as a solo line; Nicholas Milne also contributes a reviewer) of string-playing, we will begin with recordings stunning performance of the solo line of Ortíz’s recercada http://em.oxfordjournals.org/ that feature some fine performances on wind instruments.