The Limits of Idealism: When Good Intentions Go Bad (Clinical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCTOR WHO by Matthew Jacobs Mysterious Theatre 337 – Show 200402 Part 2 - Revision 2 by the Usual Suspects Transcription by Steve Hill

DOCTOR WHO By Matthew Jacobs Mysterious Theatre 337 – Show 200402 Part 2 - Revision 2 By the usual suspects Transcription by Steve Hill (Continued from part 1) EVERYONE Thirty seconds! Twenty-nine! Twenty-eight! Twenty-seven! Twenty-six! Twenty-five! SCOTT: At least they can count. Back in the Tardis it continues. EVERYONE Twenty. Nineteen. Eighteen. EVERYONE Seventeen. Sixteen. Fifteen. SCOTT: (whenever the Master/Doctor head vibration happens) (make wibble noise) EVERYONE Twelve! Eleven! Ten! GRACE I thought surgery was difficult. RICK: Obviously it is since you killed him. EVERYONE Nine! Lightning strikes up outside. EVERYONE SCOTT: Activate the device already, bee-yatch! Eight! GRACE Re - - routing the power. MASTER I'm alive. EVERYONE Seven! GRACE I'm re-routing the power. Ow! EVERYONE Six. MASTER I'm alive. I'm alive! NEWS That's all the time we have. ALL: OK, bye! EVERYONE Three! MASTER I am alive! EVERYONE (WAGG) One! (pop) DAVE: Pop goes the weasel. Grace connects the wires, the console sparks and comes to life. Fireworks outside, clocks changing, the time rotor starting and the ROB: (12:00, tinkly music) (Wicked witch music) column beginning to move. Grace looks at the console, the clock is RICK: It's a twister! Auntie Em! Auntie Em! running backward. The Tardis is caught in a whirlwind of light and is suddenly gone. DOCTOR (flashback v.o.) We have to go back to before the eye was opened, maybe even before we arrived. 1 GRACE Alarm clock, alarm clock, think alarm clock. Entering temporal orbit, says the screen. GRACE Temporal orbit? What's a temporal orbit? ROB: (as Grace) I can figure out dimensional transference, but I don't know what a temporal orbit is! We get the stretchy shots and rapid editing that is supposed to look cool DAVE: (stretchy) 2000: The Year Things Went Stretchy. -

Miriam Bostwick

Animal News from Heaven Miriam Bostwick Copyright 2014 by Paws of the Earth Productions All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the author except in critical articles and reviews. Contact the publisher for information: Paws of the Earth Productions 2980 S Jones Blvd Suite 3373 Las Vegas, NV 89146 Printed in The United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2008921323 ISBN 978-0-9798828-2-1 Paws of the Earth productions Las Vegas, NV 89146 www.Animals are people too.com This book is dedicated to the late Miriam Bostwick, a friend, a fellow lover of animals, who is among her friends in this book: I am grateful to the many spirits who so willingly shared their stories about the work they are doing in spirit and the animals they are caring for. I am also grateful to Carla Gee and Elizabeth Jordan for their invaluable editorial help. I acknowledge information obtained from Wikipedia under the GNU Free Documentation License for the following articles: Slats, the MGM Leo, the Lion Barbaro, the Race Horse Bubba, the Grouper Bubba, the Lobster Harriet, the Tortoise Binky & Nuka, Polar Bears Martha, the Passenger Pigeon Ruby, the Painting Elephant PAWS OF THE EARTH PRODUCTIONS LAS VEGAS, NEVADA Contents Preface Introduction PART ONE Lifting the Veil: Animals in the Afterlife Do all animals survive and where do they go? Love keeps an animal in form The plight of the unloved or mistreated animal Are there barriers in spirit life to divide humans and animals? How do animals in spirit get along with each other? The animal mind Healing through change in attitude Animals trained to do rescue work Separation through evolution Veterinary research in spirit life PART TWO News from Heaven The Caretakers Reggie Gonzales: On Being a Caretaker Roger Parker: On Being a Caretaker St. -

The State of Animal Welfare

OUSA PRESENTS IN ASSOCIATION WITH RADIO ONE BATTLEBATTLE of the BANDSBANDS 2012 ENTER NOW! ENTRIES CLOSE APRIL 26 COMPETITION 4-26 MAY AT REFUEL, ENTER ONLINE AT OUSA.ORG.NZ Department of Music 2 Critic Issue 07 CriticIssue 07 Broadcasting Standards Authority agrees: stoners are cool | Page 6 Th e BSA rules in favour of Radio One over their pro-cannabis show Overgrown; stoners and civil libertarians rejoice. Deep within the Clocktower, the Council meets | Page 10 Just cause we know you love elections, we’ve got another one for you! Th is time it is the student seats on the Uni council that are up for grabs. Check out the candidates and their promises. If you don’t like this status, we are going to shoot this poor African child | Page 19 Maddy Phillipps takes on Kony2012 and leaves Jason Russell in a naked quivering masturbating mess. Animals are people too | Page 22 Katie Kenny talks about zombie hens and the state of animal welfare. News 6–13 | Sports 14–15 | Politics 16–17 | Features 18–25 Columns 26–31 | Culture 32–39 | Letters 40 Critic is a member of the Aotearoa Student Press Association (ASPA). Disclaimer: the views presented within this publication do not necessarily represent the views of the Editor, Planet Media, or OUSA. Press Council: people with a complaint against a newspaper should fi rst complain in writing to the Editor and then, if not satisfi ed with the response, complain to the Press Council. Complaints should be addressed to the Secretary, PO Box 10-879 Th e Terrace, Wellington. -

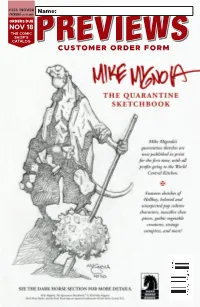

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

Kay Handbook

Kansas Association For Youth 2009-2010 KAY HANDBOOK KANSAS STATE HIGH SCHOOL ACTIVITIES ASSOCIATION PO Box 495, Topeka, KS 66601-0495 ● PH: 785 273-5329 ● FAX: 785 271-0236 [email protected] ● www.kshsaa.org KAY List of Regular Mailings & Approximate Dates Aug. 1-Aug. 20 New school year material mailed to clubs when KSHSAA receives Form KAY-1 (see your principal for form) Mailing includes: letter, Handbook, on- line information, membership cards, KAY posters and brochures, etc. September 15 Regional Conference information • Invitation to serve as Officer Network speaker • Area President nomination materials • Goal Award Status • Alloted conference delegates Early December Unit Conference information • Citizenship Week Proclamation • Holiday Greetings March 1 KAY Leadership Camp materials • Letter • State Track Program sales information • Brochures • Camp scholarship information • Posters April 1 • Spring Bulletin • Regional & Unit Conference information • Election Ideas • Transition of Leadership • End-of-year checklist PLEASE NOTE: If you do not receive the above mailings within a reasonable time period, please contact the KAY State Office. CLUBS ARE ENCOURAGED TO COPY UPDATED HANDBOOK MATERIALS (AVAILABLE ONLINE) AND PLACE IN THEIR 3-RING KAY NOTEBOOKS! (Rev. 2009) KAY HANDBOOK KANSAS ASSOCIATION for Youth an activity sponsored by the Kansas State High School Activities Association PO Box 495, Topeka, KS 66601-0495 PH: 785 273-5329 • FAX: 785 271-0236 • WEB: www.kshsaa.org FOREWORD The Kansas Association for Youth (KAY) is a character-building, leadership-training program directed by the Kansas State High School Activities Association. Club service projects, programs and parties give the student members an opportunity to participate in a citizenship laboratory. -

Fryer Per LH9.U6 S46

Fryer Per LH9.U6 S46 eDITOrial "Sometimes and in spite of our surface confidence democracy & social change. Semper 0 also begins we all experience moments in our lives in which we what we hope will be an ongoing comprehensive, are but as petrified sparrows, caught in the glare of and intelligent review section; and hurls a few cre a madman's headlights. " ative splashes in the direction of Adoptive Style in the form of SHOCK!, Refec Barbie, and other Not the BiTe team! We present the O-week installments. The paucity of available intelligences issue of Semper, Semper O, with a brazen confi over the summer season has meant not only hefty dence in our audience's ability to discern the all- internal production on the part of the editors (some embracing creative potential that lies behind this oth thing we trust will soon change), but postponing new erwise skimpily-clad first issue. Semper 0 begins by regular features until the next issue. That's the hint taking an external media environment as its sketch- and here's the incentive: if you gain nothing else able landscape and trigger for self-justification. from the sub-theme, gain this; as an 'independent, Youth media access is currently a provocative topic provocative, intelligent and accountable' young per thanks to recent critiques such as gangland (an son's voice within a ferociously restrictive main extract of which is reprinted in these pages) and stream media environment, Semper Floreat is a rare, 'industry solutions' such as the LOUD festival. Our rare beast indeed, and with your help can in 1998 be sketch includes a large nod in the direction of as its name reminds us, always flourishing. -

Greg Bear Latest Book and Comic News

NEWSLETTER OF THE IRISH SCIENCE FICTION ASSOCIATION INTERVIEWS: GREG BEAR & NICHOLAS MEYER SPIELBERG'S 'HOOK' REVIEWED LATEST BOOK AND COMIC NEWS ASIMOVTRIBUTES CONTENTS EDITORIAL EDITORIAL 2 NEWS 3 The ISFA is in Its fourth year since Nebula Award Nominations being reformed. When we started MEDIA NEWS 5 in 1988 we decided to keep it small Brussels SF Film Festival and gradually grow, depending on Video preview the resources we had available. 'Hook' reviewed ISFA NEWS 8 We decided to essentially adopt CONVENTIONS 10 the aims of the old Association, CLUBS 11 namely promoting interest in sci INTERVIEW: 12 ence fiction and Its related gen Face to Face with Nicholas Meyer res. This was to be achieved LETTERS 15 through regular meetings, work Asimov Tributes shops and publications. FTL was UPCOMING BOOKS 20 the first publication, appearing in INTERVIEW: 21 A5 format and edited by John Greg Bear Kenny for issues 1 and 2. Its aims were to provide a platform for Irish REVIEWS 24 writers of fiction and articles, inter JUST FINISHED 32 views and reviews. Artists, both THE COMICS COLUMN 32 illustrative and comic were to be OUT OF GAFIA 35 showcased. With the advent of the fully printed version last year the possibilities for expanding in terest in science fiction, especially in the art field, grew hugely. The second publication, the Newslet ter, appeared in 1990 and basi cally deals with reviews, news and, PRODUCTION recently, interviews. EDITOR: BRENDAN RYDER However the printed version of FTL COLLATING: ISFA COMMITTEE takes up a. lot of our resources, financial and people. -

Goodies Rule – OK?

This preview contains the first part ofChapter 14, covering the year 1976 and part of Appendix A which covers the first few episodes in Series Six of The Goodies THE GOODIES SUPER CHAPS THREE 1976 / SERIES 6 PREVIEW Kaleidoscope Publishing The Goodies: Super Chaps Three will be published on 8 November 2010 CONTENTS Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................7 ‘Well – so much for Winchester and Cambridge’ (1940-63) ...............................................................................................9 ‘But they’re not art lovers! They’re Americans!’ (1964-65) .............................................................................................23 ‘It’s a great act! I do all the stuff!’ (1965-66) ...................................................................................................................................31 ‘Give these boys a series’ (1967) .....................................................................................................................................................................49 ‘Our programme’s gonna be on in a minute’ (1968-69)THE .......................................................................................................65 ‘We shall all be stars!’ (1969-70) .....................................................................................................................................................................87 -

Customer Order Form

#376 | JAN20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JAN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/5/2019 4:59:33 PM Jan20 Ad DST Catwoman.indd 1 12/5/2019 3:43:15 PM PREMIER COMICS DECORUM #1 IMAGE COMICS 50 MIRKA ANDOLFO’S MERCY #1 IMAGE COMICS 54 X-RAY ROBOT #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 94 STARSHIP DOWN #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 96 ROBIN 80TH ANNIVERSARY 100-PAGE SPECTACULAR #1 DC COMICS DCP-1 STRANGE ADVENTURES #1 DC COMICS DCP-3 TRANSFORMERS VS. TERMINATOR #1 IDW PUBLISHING 130 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG ANNUAL 2020 IDW PUBLISHING 137 SPIDER-WOMAN #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-8 KILLING RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 168 KING OF NOWHERE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 204 Jan20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/5/2019 10:58:38 AM COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Vampire State Building HC l ABLAZE The Man Who Effed Up Time #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Second Coming Volume 1 TP l AHOY COMICS The Spirit 80th Anniversary Celebration TP l CLOVER PRESS Marvel: We Are Super Heroes HC l DK PUBLISHING CO FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS 1 Amazing Spider-Man: My Mighty Marvel First Book Board Book l ABRAMS APPLESEED Captain America: My Mighty Marvel First Book Board Book l ABRAMS APPLESEED Artemis and the Assassin #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Billionaire Island #1 l AHOY COMICS Hatchet: Unstoppable Horror #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS 1 Cayrel’s Ring HC l A WAVE BLUE WORLD INC Resistance #1 l ARTISTS WRITERS & ARTISANS INC Doctor Who: At Childhood’s End HC l BBC BOOKS Tarot: Witch of the Black Rose #121 l BROADSWORD COMICS Butcher Knight TP l CLOVER PRESS, LLC Dragon Hoops HC l :01 FIRST SECOND The Fire Never Goes Out: A Memoir In Pictures HC l HARPER TEEN Hexagon #1 l IMPACT THEORY, LLC Star Trek: Kirk-Fu Manual HC l INSIGHT EDITIONS Dryad #1 l ONI PRESS The Mythics Vol. -

Faith Stealer Free

FREE FAITH STEALER PDF Graham Duff,Paul McGann,India Fisher,Conrad Westmaas | none | 01 Oct 2004 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844351039 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Faith Stealer - Wikipedia Post a comment. Untitled Page. Gary Russell. But under the guidance of the charismatic Laan Carder, one religion seems to be gathering Faith Stealer at an alarming rate. With the Doctor Faith Stealer Charley catching Faith Stealer of an old friend and C'rizz on the receiving end of some unorthodox religious practices, their belief, hope and faith are about to be tested to the limit. It's time to see the light. Considering my allergic reaction to the last season you can imagine my delight in heading back to the Divergent Universe. Upon entering the Multihaven he is forced to invent his own religion, the Tourists, who start each day with a ritual cup of tea. Faith Stealer all the good work to make him witty and fun to be around again is jettisoned when he stops Charley from being brutally murdered. There is no Faith Stealer of his hunt for Rassilon, which was excitedly whispered at Faith Stealer close of the last story in the Universe. He witnesses his worst nightmare, the TARDIS bursting into a million shards and thus is trapped on this planet with no escape. He thinks it is time he came out of the closet, Faith Stealer is about damn time. There are no stunning revelations about the Doctor, no deep insights but Faith Faith Stealer features the most responsible take on his character since Neverland and for that I am grateful. -

Scotland ^ 37Th Annual Smithsonian

SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL SCOTLAND ^ 37TH ANNUAL SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE FESTIVAL Appalachia Heritage and Haniioiiy Mali From Timbuktu to Washingto ii Scotland at the Smithsonian June 2 5 -July 6, 2003 Wa s h i n g t o n , D . C . The annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival brings together exemplary keepers of diverse traditions, both old and new. from communities across the United States and around the world. The goal of the Festival is to strengthen and preserve these traditions by presenting them on the National MaO, so that the tradition-hearers and the public can connect with and learn from one another, and understand cultural difierences in a respectful way. Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 750 9th Street NW Suite 4100 Washington, DC 20560-0953 www. folklife. SI . edu © 2003 by the Smithsonian Institution ISSN 1056-6805 Editor: Carla Borden Associate Editors: Frank Proschan, Peter Seitel Art Director: Denise Arnot Production Manager: Joan Erdesky Design Assistant: Krystyn MacGregor Confair Printing: Finlay Printing, Bloomfield, CT Festival Sponsors The Festival is co-sponsored by the National Park Service. The Festival is supported by federally appropriated funds; Smithsonian trust funds; contributions from governments, businesses, foundations, and individuals; in-kind assistance; volunteers; and food, recording, and craft sales. Major in-kind support for the Festival has been provided by media partners WAMU 88.5 FM—American University Radio, Tfie IVashiiigtoii Post, washingtonpost.com, and Afropop, and by Motorola, Nextel, Whole Foods Market, and Go-Ped. APPALACHIA: HERITAGE AND HARMONY This program is produced in collaboration with the Birthplace of Country Music Alliance and the Center for Appalachian Studies at East Tennessee State University. -

May 10, 2017, Vegetarian Action Newsletter

VEGETARIAN ACTION NEWSLETTER #37 MAY 10, 2017. http://jamesrichardbennett.blogspot.com/2017/05/omni-vegetarian- action-newsletter-37.html Edited by Dick Bennett for a Culture of Peace, Justice, and Ecology http://omnicenter.org/donate/ OMNI’s MAY VEGETARIAN POTLUCK is Wednesday, MAY 10, at OMNI, Center for Peace, Justice, and Ecology (2ND Wednesdays) at the OMNI Center for Peace, Justice, and Ecology. We usually begin at 6:00, but tonight we’re showing a film, so I will be coming early. All are welcome. You may want to enjoy some old or new vegetarian recipes,and discuss them, to talk about healthier food, or you are concerned about cruelty to animals or warming and climate change. Whatever your interest it’s connected to plant or meat eating; whatever your motive, come share vegetarian and vegan food and your views with us in a friendly setting. As an extra treat, thanks to Bob Walker we will be showing the new film What the Health! created by the makers of Cowspiracy. We would have more films and programs if we had the money, so please give a donation. If you are new, get acquainted with OMNI’s director, Gladys. At OMNI, 3274 Lee Avenue, off N. College east of the Village Inn and south of Liquor World. More information: 935-4422; 442-4600. Contents: Vegetarian Action Newsletter #37, May 10, 2017 Vegan Poetry Dr Ravi P Bhatia. Seeking Peace in Vegetarianism Health, Nutrition VegNews each number packed with articles, recipes, ads for products about veg/vegan food. What the Health! New film about meat eating/carnivorism vs.