South Sudanese Refugee Project Gulu, Kampala & Arua, Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CARE for PEOPLE LIVING with DISABILITIES in the WEST NILE REGION of UGANDA:: 7(3) 180-198 UMU Press 2009

CARE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DISABILITIES IN THE WEST NILE REGION OF UGANDA:: 7(3) 180-198 UMU Press 2009 CARE FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH DISABILITIES IN THE WEST NILE REGION OF UGANDA: EX-POST EVALUATION OF A PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTED BY DOCTORS WITH AFRICA CUAMM Maria-Pia Waelkens#, Everd Maniple and Stella Regina Nakiwala, Faculty of Health Sciences, Uganda Martyrs University, P.O. Box 5498 Kampala, Uganda. #Corresponding author e-mail addresses: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Disability is a common occurrence in many countries and a subject of much discussion and lobby. People with disability (PWD) are frequently segregated in society and by-passed for many opportunities. Stigma hinders their potential contribution to society. Doctors with Africa CUAMM, an Italian NGO, started a project to improve the life of PWD in the West Nile region in north- western Uganda in 2003. An orthopaedic workshop, a physiotherapy unit and a community-based rehabilitation programme were set up as part of the project. This ex-post evaluation found that the project made an important contribution to the life of the PWD through its activities, which were handed over to the local referral hospital for continuation after three years. The services have been maintained and their utilisation has been expanded through a network of outreach clinics. Community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers mobilise the community for disability assessment and supplement the output of qualified health workers in service delivery. However, the quality of care during clinics is still poor on account of large numbers. In the face of the departure of the international NGO, a new local NGO has been formed by stakeholders to take over some functions previously done by the international NGO, such as advocacy and resource mobilisation. -

Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in Two Refugee Settlements of Uganda

X Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in two Refugee Settlements of Uganda X Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in two Refugee Settlements of Uganda Copyright © International Labour Organization 2021 First published 2021 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publishing (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The ILO and FAO welcome such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Impact of COVID-19 on Refugee and Host Community Livelihoods ILO PROSPECTS Rapid Assessment in two Refugee Settlements of Uganda ISBN 978-92-2-034720-1 (Print) ISBN 978-92-2-034719-5 (Web PDF) The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Annual Insurance Market Report 2018 Annual Insurance Market Report

2018 ANNUAL INSURANCE MARKET REPORT 2018 ANNUAL INSURANCE MARKET REPORT 2 Insurance Regulatory Authority of Uganda | ANNUAL INSURANCE MARKET REPORT 2018 Strategic Overview of IRA Our Business Who we Are We are the Insurance Regulatory Authority of Uganda whose establishment was a consequence of Government’s adoption of the Liberalization policy which ended its role of directly engaging in the provision of goods and services and taking on the role of Supervision and Regulation. The Authority is the Supervisor and Regulator of the insurance industry in Uganda. It was established under the Insurance Act, (Cap 213) Laws of Uganda, 2000 (as amended) with the main objective of “ensuring Effective Administration, Supervision, Regulation and Control of the business of insurance in Uganda”. In addition to maintaining the safety and sound operation of insurance players, protecting the interests of insureds and insurance beneficiaries and ensuring the supply of high quality and transparent insurance services and products, the Authority commits significant efforts and resources to facilitating the development of the insurance market. Our Mission To create an enabling regulatory environment for sustainable growth of the insurance industry while upholding best practices. Our Vision A Model Regulator of a Developed and secure insurance industry Our Values The Insurance Regulatory Authority has five core values, namely: I) Professionalism - We are qualified, skilled and act with the highest standards of excellence. II) Integrity - We model ethical behaviour by conducting all matters of business with integrity. III) Accountability - We accept responsibility for our actions. IV) Transparency – We are open and honest in communication V) Team Work – We are better together. -

REPUBLIC of UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY

E1879 VOL.3 REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY FINAL DETAILED ENGINEERING Public Disclosure Authorized DESIGN REPORT CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN FOR UPGRADING TO PAVED (BITUMEN) STANDARD OF VURRA-ARUA-KOBOKO-ORABA ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized VOL IV - ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized The Executive Director Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) Plot 11 Yusuf Lule Road P.O.Box AN 7917 P.O.Box 28487 Accra-North Kampala, Uganda Ghana Feasibility Study and Detailed Design ofVurra-Arua-Koboko-Road Environmental Social Impact Assessment Final Detailed Engineering Design Report TABLE OF CONTENTS o EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 0-1 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ROAD........................................................................................ I-I 1.3 NEED FOR AN ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDy ...................................... 1-3 1.4 OBJECTIVES OF THE ESIA STUDY ............................................................................................... 1-3 2 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 INITIAL MEETINGS WITH NEMA AND UNRA............................................................................ -

ARUA BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 503 Arua District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2014/15 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 503 Arua District Foreword Am delighted to present the Arua District Local Government Budget Framework Paper for Financial Year 2014/15. the Local Government Budget framework paper has been prepared with the collaboration and participation of members of the District Council, Civil Society Organozations and Lower Local Governments and other stakeholders during a one day budgtet conference held on 14th September 2013. The District Budget conferences provided an opportujity to intergrate the key policy issues and priorities of all stakeholders into the sectoral plans. The BFP represents the continued commitment of the District in joining hands with the Central Government to promote Growth, Employment and Prosperity for financial year 2014/15 in line with the theme of the National Development Plan. This theme is embodied in our District vision of having a healthy, productive and prosperious people by 2017. The overall purpose of the BFP is to enable Arua District Council, plan and Budget for revenue and expenditure items within the given resoruce envelop. Local Revenue, Central Government Transfers and Donor funds, finance the short tem and medium tem expenditure frame work. The BFP raises key development concerns for incorporation into the National Budget Framework Paper. The BFP has been prepared in three main sections. It has taken into account the approved five year development plan and Local Economic Development Strategy. -

Female Educators in Uganda

Female Educators in Uganda UNDERSTANDING PROFESSIONAL WELFARE IN GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOLS WITH REFUGEE STUDENTS Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies & Creative Associates International SPRING 2019 | SAIS WOMEN LEAD PRACTICUM PROGRAM Table of Contents TABLE OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... III ABOUT THE AUTHORS ......................................................................................................... IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... V ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................... VI MAP OF UGANDA............................................................................................................. VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 10 2. BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW...................................................................... 13 3. METHODOLOGY & RESULTS ........................................................................................... 18 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................................... 18 ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................... -

MVARA PROFILE Urban Community Assessment

MVARA PROFILE Urban community assessment Arua, Uganda - August 2018 Supported by In partnership with Implemented by ♊ CONTEXT ♠ ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND Bordered by several of the largest refugee-generating countries in the world, Some 60% of refugees worldwide live out of camps—and the majority live Uganda hosts the largest population of refugees on the African continent. in urban centres. A broad consensus across the humanitarian sector has been Since the 2016 crisis, between 600,000-800,000 South Sudanese refugees reached to improve support of out-of-camp refugees. Despite this, assistance to have made their way to Uganda, joined by large refugee populations from the out-of-camp refugees remains largely ad-hoc and uncoordinated. Underpinning Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Burundi, and Somalia. Humanitarian this humanitarian shortcoming is a lack of understanding and effective engagement needs are accordingly significant. According to the United Nations High with the complex dynamics facing refugees and host communities in cities. Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), an anticipated 100,000 additional South Sudanese refugees are due to arrive this year.1 Accompanied by rapidly This is also the case in Arua, where refugees lack access to humanitarian growing numbers of new arrivals from DRC, the need for humanitarian aid has assistance in the city and attempts by local authorities at providing services are only increased throughout 2018. Current population figures are being evaluated complicated by a lack of in-depth information on displacement dynamics. To as part of a re-verification process by UNCHR and the Ugandan Office of the address these challenges, this assessment aims to fill the information gaps on Prime Minister (OPM) to assess the current number of refugees residing in urban displaced populations in Arua, to assess their needs, and to gauge service 2 settlements across Uganda. -

Arua District Investment Profile

ARUA DISTRICT INVESTMENT PROFILE Uganda ARUA DISTRICT | Figure 1: Map of Uganda showing the location of Arua District 2 ARUA DISTRICT INVESTMENT PROFILE SNAPSHOT ONARUA Geography Location: West Nile Neighbors: Maracha, Koboko, Yumbe, Adjumani, Nebbi, Zombo District area: 4,274.13 Km2 Arable land area: 3,718.86 Km2 Socio-Economic Characteristics Population (2016 projection): 820,500 Refugees and Asylum seekers (April 211,749 (26%) 2017): Languages: Lugbara, English, Kiswahili, Lingala and Arabic Main Economic Activity: Agriculture Major tradeables: Cassava, Sweet Potatoes and Plantain Market target: 71 million, including DRC and South Sudan Infrastructure and strategic positioning Transport network: Arua Airport; (road network) Communication: MTN, Airtel, Africel, UTL, the internet GEOGRAPHY  Arua district lies in the  In total the district covers an North-Western Corner of Ugan- area of 4,274.13Km2, of which da. It is bordered by Maracha about 87% is arable. It is located district in the North West; Yum- 520 km from Kampala and only be in the North East; Democratic 80 km from the South Sudan Republic of Congo in the West; Border. Nebbi in the South; Zombo in the South East; and Amuru district in the East. ARUA DISTRICT INVESTMENT PROFILE 3 DEMOGRAPHY  Arua town is very busy and cos-  The refugees, mainly from South mopolitan, with major languag- Sudan are of diverse ethnic es: English, Kiswahili, Lingala backgrounds; Dinkas, Kuku, Nuer, and Arabic and many local Kakwa, Madi, and Siluk and have dialects widely spoken, and mul- close ethnicity with the locals tiple cultures freely celebrated. who are Kakwa, Madi, Alur and This demonstrates the unique Lugbara. -

ARUA BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 503 Arua District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2013/14 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 503 Arua District Foreword Am delighted to present the Arua District Local Government Budget Framework Paper for Financial Year 2013/14. the Local Government Budget framework paper has been prepared with the collaboration and participation of members of the District Council, Civil Society Organozations and Lower Local Governments and other stakeholders during a one day budgtet conference held on 5th March 2013. the District Budget conferences provided an opportujity to intergrate the key policy issues and priorities of all stakeholders into the sectoral plans. The BFP represents the continued commitment of the District joining hands with the Central Government to promote Growth, Employment and Prosperity for financial year 2013/14 in line with the theme of the National Development Plan. This theme is embodied in our District vision of having a healthy, productive and prosperious people by 2017. The overall purpose of the BFP is to enable Arua District Council, plan and Budget for revenue and expenditure items within the given resoruce envelop. Local Revenue, Central Government Transfers and Donor funds, finance the short tem and medium tem expenditure frame work. The BFP raises key development concerns for incorporation into the National Budget Framework Paper. The BFP has been prepared in four sections and offers the key development challenges and strategic objectives of the Arua District Council. -

Arua District

UGANDA - Arua District - Base map Otravu Alibabito au Eny Ewafa Naiforo Cilio Tondolo MOYO Ongoro Olovu Achimari Koyi Obuje Dilakate Apaa YUMBE Adu Atubanga Leju Wawa Arara Oluffe Alinga Aterodri Lamila Aripea HC III Otrevu Ewanga Alibabito Ambidro Paranga Yazo Odranlere Ale Kamadi Aranga Atratraka Kijomoro Alivu Ngurua Owafa Orukurua Aiivu Angilia Owaffa Ejomi Adzuani Rubu Simbili Aringa Terego Ariwara Obisa Angilia Male ETHIOPIA Djawudjawu Kijoro Lokiragodo Katrini SOUTH SUDAN Tseko Nderi Ombatini Akei Kamatsau Michu Kidjoro kubo Koboko - Arua Road Aliba MARACHA Nyaute Oriajini Waka Angiria Lolo Ombayi Nderi AROI Hospital NORTHERN REGION Tshakay Ayiko Sua Lolo Maracha Otumbari Mingoro Wandi Yoro Wanyange DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Ewadri EASTERN AYIVUNI Anzaiya Okalara REGION KENYA Imvenga Ombayi MANIBE Lukuma WESTERN Abia REGION Kampala Azokini Abi Yole Ocodri CENTRAL Ombai Ocodri HC III REGION Kuku RIGBO Kari Kuku Oleko Bilefe Ombaci Wanica Kikia Mbaraka UNITED REPUBLIC OF Ayivu Oreko RWANDA Uzu Fundu TANZANIA Paraka Wiria Panduru Adumi Ombache Rigbo Essoko Oyo Adumi Road Tangala Pajulu LEGEND Essoko Odro Arivu Mite ADUMI Nvio Odoi Obuin Oria Mite Ombayi Mariestopes RIVER DADAMU Isakua Admin capital lvl 2 Essoko Essoko Omi Uganda OLI Kulekule Uluko Curu ADJUMANI Main town Ombo Nono-Anyavo Arua Regional Kaligo AruaAnyau OLUKO Nyio Pajulu Ayivu County Village Ova Referral Hospital RHINO CAMP Onari Nono-Omi Arua Hill Nono-Nyai PAJULU A Bulukatoni Bismilai Hospital Ovua n Ampi Nono-ayiko Ovoa y Matangacha Nono-Ayia Giligili a u -

UG-Plan-25 A3 24July09 West Nile Region Planning Map - General United Nations

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org WEST NILE SUB-REGION: PLANNING MAP (General) SUDAN METU West MIDIGO Moyo MOYO TC (! KEI ! Moyo LUDARA LEFORI MOYO Nimule MOYO DUFILE ! KULUBA Laropi YUMBE ! Koboko KOBOKO)"(! Aringa ROMOGI (! YUMBE )" )" TC APO ADROPI ! Yumbe ITULA Koboko DZAIPI ! LOBULE Lodonga KOBOKO TC ! KURU Adjumani ! MIDIA Obongi DRAJANI (! ADJUMANI TC Obongi ODRAVU ! OLEBA TARA GIMARA Maracha Omugo ! ! East Maracha YIVU OMUGO MARACHA (! Moyo OLUFFE )"(! NYADRI (NYADRI) ADJUMANI PAKELLE ALIBA AII-VU )" Terego (! ODUPI OLUVU KIJOMORO Te re go ! KATRINI OFUA URIAMA AROI MANIBE RIGBO ADUMI Ayivu BELEAFE DADAMU (! OLI RIVER CIFORO ! Arua(! OLUKO RHINO ARUA CAMP HILL PAJULU Rhino Camp ! VURRA AJIA Bondo )" ! Inde Madi- Aru ! ! Okollo )" (! Vurra (! ARUA OGOKO ARIVU ULEPPI Uleppi ! LOGIRI OKOLLO AMURU Okollo ! WADELAI OFFAKA War Lolim KANGO ! ! ATYAK Anaka ! Lalem ! Nwoya Okoro NEBBI (! (! KUCWINY PANYANGO NYAPEA PAKWACH TC ZEU PAIDHA NEBBI TC Jonam )" (! ! Pakwach Padyere NEBBI (! JANGOKORO PAIDHA TC NYARAVUR Goli Pakuba ! ! ERUSSI PAKWACH PAROMBO PANYIMUR Parombo ! Panyimur Paraa ! ! AKWORO Wanseko ! CONGO MASINDI Bulisa (DEM.REP) ! Uganda Overview Mahagi- BULIISA port ! Sudan Congo Legend This map is a work in progress. Data Sources: Map Disclaimer: (Dem.Rep) Please contact the IMU/Ocha Draft )" Landuse Type District Admin Centres Motorable Road National Park as soon as possible with any Admin Boundaries - UBOS 2006 The boundaries and names Forest Reserve corrections. K Admin Centres - UBOS 2002/2006 shown and the designations Kenya (! County Admin Centres District Boundary Rangeland 010205 Landuse - UBOS 2006 used on this map do not imply Game Reserve Kilometers ! To wns County Boundary Water Body/Lakes Road Network - FAO official endorsement or Map Prepare Date: 24 July 2009 (IMU/UNOCHA, Kampala) Towns - Humanitarian Agencies in the field acceptance by the Tanzania Label Sub-County Boundary File: UG-Plan-25_A3_24July09_West Nile Region Planning Map - General United Nations. -

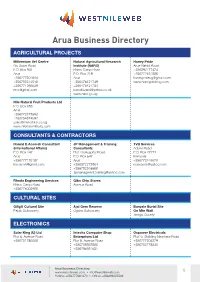

Arua Business Directory.Indd

Arua Business Directory AGRICULTURAL PROJECTS Millennium Vet Centre Natural Agricultural Research Honey Pride Go Down Road Institute (NARO) Arua-Nebbi Road P.O. Box 941 Rhino Camp Road +256392177474 Arua P.O. Box 219 +256772451586 +256777301694 Arua [email protected] +256785514518 +256476421749 www.honeyprideug.com +256771296029 +256476421734 [email protected] [email protected] www.naro.go.ug Nile Natural Fruit Products Ltd P.O. Box 685 Arua +256772373692 +256754374692 [email protected] www.nilenaturalfruits.com CONSULTANTS & CONTRACTORS Harold E.Acemah Consultant JP Management & Training TVB Services (International Affairs) Consultants Adumi Road P.O. Box 147 Plot 10,Hospital Road P.O. Box 27772 Arua P.O. Box 647 Kampala +256777175187 Arua +256772446676 [email protected] +256372273964 [email protected] +256782346688 [email protected] Rhoda Engineering Services Gibo Chip Stores Rhino Camp Road Avenue Road +256776002988 CULTURAL SITES Giligili Cultural Site Ajai Gem Reserve Banyale Burial Site Pajulu Subcounty Ogoko Subcounty On Mtn Wati Terego County ELECTRONICS Solar King (U) Ltd Intechs Computer Shop Ospower Electricals Plot 6, Avenue Road Enterprises Ltd Plot14, Building New lane Road +256751786008 Plot 8, Avenue Road +256777204279 +256758353856 +256752778540 +256786931631 Arua Business Directory www.westnileweb.com • [email protected] 1 Hotline: +256777681670 • Office: +256393225533 Metro Electronics Arua Phones Service Centre Aliza Electronic Ltd Plot 10, Duka Road Plot12, Avenue Road Avenue Road +256702144786 +256772822122 +256715089299 +256713144786 Holly Wood Electronics (U) Roman Electronics (U) Ltd Plot1- 3, Adumi Road Adumi Road +256713144786 +256778134910 FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS Centenary Bank Stanbic Bank Bank of Africa Plot 3, Avenue Road Avenue Road Plot 19, Avenue Road P.O.