Dose-Response Efficacy of Valsartan, a New Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diovan® Valsartan

NDA 21-283/S-011 Page 3 T2005-02 Diovan® valsartan Tablets Rx only Prescribing Information USE IN PREGNANCY When used in pregnancy during the second and third trimesters, drugs that act directly on the renin-angiotensin system can cause injury and even death to the developing fetus. When pregnancy is detected, Diovan should be discontinued as soon as possible. See WARNINGS: Fetal/Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality. DESCRIPTION Diovan® (valsartan) is a nonpeptide, orally active, and specific angiotensin II antagonist acting on the AT1 receptor subtype. Valsartan is chemically described as N-(1-oxopentyl)-N-[[2′-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl) [1,1′-biphenyl]- 4-yl]methyl]-L-valine. Its empirical formula is C24H29N5O3, its molecular weight is 435.5, and its structural formula is Valsartan is a white to practically white fine powder. It is soluble in ethanol and methanol and slightly soluble in water. NDA 21-283/S-011 Page 4 Diovan is available as tablets for oral administration, containing 40 mg, 80 mg, 160 mg or 320 mg of valsartan. The inactive ingredients of the tablets are colloidal silicon dioxide, crospovidone, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose, iron oxides (yellow, black and/or red), magnesium stearate, microcrystalline cellulose, polyethylene glycol 8000, and titanium dioxide. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mechanism of Action Angiotensin II is formed from angiotensin I in a reaction catalyzed by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE, kininase II). Angiotensin II is the principal pressor agent of the renin-angiotensin system, with effects that include vasoconstriction, stimulation of synthesis and release of aldosterone, cardiac stimulation, and renal reabsorption of sodium. Valsartan blocks the vasoconstrictor and aldosterone- secreting effects of angiotensin II by selectively blocking the binding of angiotensin II to the AT1 receptor in many tissues, such as vascular smooth muscle and the adrenal gland. -

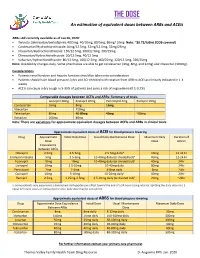

THE DOSE an Estimation of Equivalent Doses Between Arbs and Aceis

THE DOSE An estimation of equivalent doses between ARBs and ACEIs ARBs still currently available as of Jan 26, 2020: Twynsta (telmisartan/amlodipine): 40/5mg. 40/10mg, 80/5mg, 80mg/ 10mg Note: ~$0.73/tablet (ODB covered) Candesartan/Hydrochlorothiazide:16mg/12.5mg, 32mg/12.5mg, 32mg/25mg Irbesartan/Hydrochlorothiazide: 150/12.5mg, 300/12.5mg, 300/25mg Olmesartan/Hydrochlorothiaizde: 20/12.5mg, 40/12.5mg Valsartan/Hydrochlorothiazide: 80/12.5mg, 160/12.5mg, 160/25mg, 320/12.5mg, 320/25mg Note: Availability changes daily. Some pharmacies are able to get candesartan (4mg, 8mg, and 32mg) and irbesartan (300mg). Considerations Patients renal function and hepatic function should be taken into consideration Patients should have blood pressure, lytes and SCr checked with rotation from ARB to ACEI as clinically indicated in 1-4 weeks ACEIs can cause a dry cough in 5-35% of patients and carry a risk of angioedema (0.1-0.2%) Comparable dosages between ACEIs and ARBs- Summary of trials Lisinopril 20mg Enalapril 20mg Perindopril 4mg Ramipril 10mg Candesartan 16mg 8mg 16mg Irbesartan 150mg Telmisartan 80mg 40-80mg 40mg ~80mg Valsartan 160mg 80mg Note: There are variations for approximate equivalent dosages between ACEIs and ARBs in clinical trials. Approximate equivalent doses of ACEI for blood pressure lowering Drug Approximate Initial Daily Dose Usual Daily Maintenance Dose Maximum Daily Duration of Dose Dose Action Equivalence Between ACEIs Cilazapril 2.5mg 2.5-5mg 2.5-5mg dailya 10mg 12-24 hr Enalapril maleate 5mg 2.5-5mg 10-40mg daily (or divided bid)a 40mg 12-24 hr Fosinopril 10mg 10mg 10-40mg daily (or divided bid)a 40mg 24hr Lisinopril 10mg 2.5-10mg 10-40mg daily 80mg 24hr Perindopril 2mg 2-4mg 4-8mg daily 8mg 24hr Quinapril 10mg 5-10mg 10-20mg dailya 40mg 24hr Ramipril 2.5mg 1.25mg-2.5mg 2.5-10mg daily (or divided bid)a 20mg ~24hr a: Some patients may experience a diminished antihypertensive effect toward the end of a 24-hour dosing interval. -

Diovan (Valsartan) Tablets ------DOSAGE FORMS and STRENGTHS------Initial U.S

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION without food. In heart failure patients, consideration should be given to These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Diovan reducing the dose of concomitant diuretics. Following myocardial safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for Diovan. infarction, consideration should be given to a dosage reduction if symptomatic hypotension or renal dysfunction occurs. Diovan (valsartan) Tablets -----------DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS------------ Initial U.S. Approval: 1996 Tablets (mg): 40 (scored), 80, 160, 320 WARNING: USE IN PREGNANCY ---------------------CONTRAINDICATIONS------------------- When pregnancy is detected, discontinue Diovan as soon as possible. None Drugs that act directly on the renin-angiotensin system can cause injury and even death to the developing fetus (5.1) ---------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS------------ • Avoid fetal or neonatal exposure (5.1) -----------------RECENT MAJOR CHANGES----------------- • Observe for signs and symptoms of hypotension (5.2) Indications and Usage: Benefits of lowering blood pressure (1) 12/2011 • Use with caution in patients with impaired hepatic (5.3) or renal (5.4) function --------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE--------------------- Diovan is an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) indicated for: -------------------ADVERSE REACTIONS ----------------- • Treatment of hypertension, to lower blood pressure. Lowering blood Hypertension: Most common adverse reactions are headache, dizziness, pressure reduces the risk of -

Comparative Effects of Telmisartan and Valsartan As Add-On Agents For

Hypertension Research (2014) 37, 225–231 & 2014 The Japanese Society of Hypertension All rights reserved 0916-9636/14 www.nature.com/hr ORIGINAL ARTICLE Comparative effects of telmisartan and valsartan as add-on agents for hypertensive patients with morning blood pressure insufficiently controlled by amlodipine monotherapy Hideaki Yoshida1, Hiroshi Akasaka1, Shigeyuki Saitoh1, Kazuaki Shimamoto1 and Tetsuji Miura1 on behalf of the SPEED investigators2 The aim of this study was to determine the efficacies of valsartan and telmisartan as add-on agents for the control of morning blood pressure (BP) in patients already on amlodipine monotherapy. A total of 414 hypertensive patients were prospectively enrolled in a 4-week run-in period when they were treated with amlodipine (5 mg/day), and home BP was measured in the morning and evening. Patients with home systolic BP (SBP) being 135–159 mm Hg in the morning at the end of the run-in period were randomized to additional treatment with valsartan (80 mg/day) or with telmisartan (40 mg/day) for 8 weeks. The primary endpoint was the change in morning home BP, and secondary endpoints included variability of morning home BP. Of the 282 patients randomized, 262 patients (n ¼ 131, in each treatment) completed the protocols. Demographic parameters and baseline morning SBP/diastolic BP (DBP) (146.3±7.1/84.8±9.3 vs. 146.0±7.1/84.2±9.1 mm Hg) were comparable in the valsartan group and telmisartan group, and changes in SBP/DBP after 8-week treatment were not significantly different between the two groups ( À7.4±10.6/ À3.9±6.1 vs. -

Shortage of Valsartan Formulations

Shortage of Valsartan Formulations Updated 24th September 2019 Description of products affected Valsartan is an angiotensin II receptor antagonist (AIIRA) licensed for the treatment of patients with: • Hypertension. • Symptomatic heart failure. • Post- myocardial infarction (MI) with left ventricular failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD). Licensed doses range from 40mg to 320mg per day given once or twice daily depending on indication. It is one of several AIIRAs on the UK market which are all licensed for the treatment of hypertension but differ in their other licensed indications. Background • There have been intermittent supply problems with all strengths of valsartan formulations (including both capsules and tablets). • Our Medicines Optimisation Team has managed to ascertain the following availability from manufacturers as of 20th September 2019: o Crescent – Valsartan 80mg capsules and valsartan 160mg capsules are available. o DE Pharmaceuticals – Valsartan 40mg tablets and valsartan 320mg tablets are available. o Mylan – Valsartan 160mg capsules and valsartan 320mg tablets are available. • There is currently only the broad anticipated resolution date of October to November 2019. • Suppliers of alternative AIIRAs have been contacted to determine if they have sufficient stock availability and currently both Losartan and Candesartan are available from the 3 major wholesalers: AAH, Alliance HC and Phoenix. Alternative agents and suggested management options • The patient should be encouraged to try several pharmacies in order to fulfil the prescription as different pharmacies use a range of wholesalers and distributors. The patient may wish to ring pharmacies in advance of attending to ascertain availability. Page 1 of 3 • The decision about what to do will need to be individualised to each patient. -

Download Leaflet View the Patient Leaflet in PDF Format

Package leaflet: Information for the user Valsartan 40 mg hard capsules Valsartan 80 mg hard capsules Valsartan 160 mg hard capsules valsartan Read all of this leaflet carefully before you start taking this medicine because it contains important information for you. • Keep this leaflet. You may need to read it again. • If you have any further questions, ask your doctor or pharmacist. • This medicine has been prescribed for you only. Do not pass it on to others. It may harm them, even if their signs of illness are the same as yours. • If you get any side effects, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. This includes any possible side effects not listed in this leaflet. See section 4. What is in this leaflet 1. What Valsartan is and what it is used for 2. What you need to know before you take Valsartan 3. How to take Valsartan 4. Possible side effects 5. How to store Valsartan 6. Contents of the pack and other information 1. What Valsartan is and what it is used for Valsartan belongs to a class of medicines known as angiotensin II receptor antagonist, which help to control high blood pressure. Angiotensin II is a substance in the body that causes vessels to tighten, thus causing your blood pressure to increase. Valsartan works by blocking the effect of angiotensin II. As a result, blood vessels relax and blood pressure is lowered. Valsartan 40 mg hard capsules can be used for three different conditions: • to treat high blood pressure in children and adolescents 6 to 18 years of age. -

Valsartan: Pediatric Medication

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION Valsartan This information from Lexicomp® explains what you need to know about this medication, including what it’s used for, how to take it, its side effects, and when to call your healthcare provider. Brand Names: US Diovan Brand Names: Canada ACT Valsartan [DSC]; APO-Valsartan; Auro-Valsartan; Diovan; DOM-Valsartan [DSC]; MYLAN-Valsartan [DSC]; PMS-Valsartan [DSC]; RIVA-Valsartan [DSC]; SANDOZ Valsartan; TARO-Valsartan; TEVA-Valsartan Warning If your child is or may be pregnant: Do not give this drug to your child during pregnancy. Use during pregnancy may cause birth defects or loss of the unborn baby. If your child gets pregnant or plans on getting pregnant while taking this drug, call the doctor right away. What is this drug used for? It is used to treat high blood pressure. It may be given to your child for other reasons. Talk with the doctor. Valsartan 1/7 What do I need to tell the doctor BEFORE my child takes this drug? If your child is allergic to this drug; any part of this drug; or any other drugs, foods, or substances. Tell the doctor about the allergy and what signs your child had. If your child is taking a drug that has aliskiren in it and your child also has diabetes or kidney problems. If your child is breast-feeding a baby: Be sure your child does not breast-feed a baby while taking this drug. This is not a list of all drugs or health problems that interact with this drug. Tell the doctor and pharmacist about all of your child’s drugs (prescription or OTC, natural products, vitamins) and health problems. -

Valsartan, a New Angiotensin II Antagonist for the Treatment

Journal of Human Hypertension (1997) 11, 483–489 1997 Stockton Press. All rights reserved 0950-9240/97 $12.00 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Valsartan, a new angiotensin II antagonist for the treatment of essential hypertension: efficacy, tolerability and safety compared to an angiotensin- converting enzyme inhibitor, lisinopril HR Black1, A Graff2, D Shute3, R Stoltz4, D Ruff5, J Levine6, Y Shi7 and S Mallows7 1Rush-Presbyterian-St Luke’s Medical Center, Chicago, IL; 2Practice, Fort Lauderdale, FL; 3Metropolitan Clinic, Portland, OR; 4GFI Pharmaceutical Services Inc, Evansville, IN; 5Practice, San Antonio, TX; 6Practice, Nashville, TN; 7Cardiovascular Clinical Research, Ciba-Geigy Corporation, Summit, NJ, USA Objective: To compare the efficacy, safety and toler- reduction from baseline: valsartan 80/160 mg: 25.25 ability of valsartan to an angiotensin-converting enzyme mm Hg (CI 27.17, 23.34, P , 0.001); valsartan 80/80 mg (ACE) inhibitor, lisinopril, and placebo in patients with twice daily: 25.63 mm Hg (CI 27.51,23.75, P , 0.001); mild-to-moderate essential hypertension. lisinopril 10/20 mg: 26.93 mm Hg, (CI 28.81, 25.05, Design: A total of 734 men and women were randomised P , 0.001). There were no statistically significant differ- in this multicentre, double-blind, optional titration, par- ences between the active treatment groups at endpoint allel group trial. Volunteers received valsartan 80 mg (n of therapy. In patients requiring titration to a higher = 364), lisinopril 10 mg (n 5 187) or placebo (n = 183) dose (placebo n 5 142, valsartan 80/80 twice daily n 5 daily for 4 weeks, with subsequent titration of dose 124, valsartan 80/160 n 5 114, lisinopril 10/20 n 5 120), depending on response to treatment (valsartan 80 mg there were no significant treatment differences between titrated to valsartan 160 mg once daily or valsartan valsartan 160 mg given as a single daily dose or as 80 mg twice daily, lisinopril 10 mg titrated to lisonopril 80 mg twice daily (P 5 0.658). -

Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists (Arbs), Renin

Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists (ARBs), Renin Inhibitors, and Combinations Step Therapy Program Summary This program applies to Commercial, GenPlus, NetResults A series, Blue Partner, SourceRx, and Health Insurance Marketplace formularies. OBJECTIVE The intent of the Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists (ARBs), Renin Inhibitors, and Combinations Step Therapy (ST) program is to encourage use of cost-effective generic products - ACEIs, ACEI combinations (ACEI/diuretics or ACEI/calcium channel blockers [CCBs]), ARBs, or ARB combinations - over the more expensive brand ARBs, brand ARB combinations, brand renin inhibitors and renin inhibitor combinations (renin inhibitor/diuretic, renin inhibitor/ARB, or renin inhibitor/CCB). This program will accommodate for use of brand products when generic prerequisites cannot be used due to previous trial and failure, documented intolerance, FDA labeled contraindication, or hypersensitivity. Requests for brand ARB or renin inhibitor products will be reviewed when patient-specific documentation is provided. TARGET AGENTS Angiotensin II Receptor Antagonists (ARBs), Combinations Brand Generic Atacand® candesartana Atacand HCT® candesartan/HCTZab Avapro® irbesartana Avalide® irbesartan/HCTZab Azor® olmesartan/amlodipinea Benicar® olmesartana Benicar HCT® olmesartan/HCTZab Byvalson™ nebivolol/valsartan Cozaar® losartana Diovan® valsartana Diovan HCT® valsartan/HCTZab Edarbi® azilsartan Edarbyclor® azilsartan/chlorthalidone Eprosartan eprosartan Exforge® valsartan/amlodipinea Exforge HCT® valsartan/amlodipine/HCTZab -

Aliskiren, a Novel Oral Renin Inhibitor, Provides Dose-Dependent Efficacy and Placebo-Like Tolerability in Japanese Patients

997 Hypertens Res Vol.29 (2006) No.12 p.997-1005 Original Article Aliskiren, a Novel Oral Renin Inhibitor, Provides Dose-Dependent Efficacy and Placebo-Like Tolerability in Japanese Patients with Hypertension Toshio KUSHIRO1), Hiroshige ITAKURA2), Yoshihisa ABO3), Hiromi GOTOU4), Shinji TERAO5), and Deborah L. KEEFE6) Aliskiren is a novel orally active renin inhibitor for the treatment of hypertension. This study evaluated the antihypertensive efficacy, safety and tolerability of aliskiren in Japanese patients with hypertension. Forty hundred and fifty-five Japanese men and women with a mean sitting diastolic blood pressure of 95–110 mmHg were randomized to receive once-daily double-blind treatment for 8 weeks with aliskiren 75, 150 or 300 mg or placebo. Aliskiren produced significant, dose-dependent reductions in mean sitting diastolic blood pressure (p<0.0005 vs. placebo for each dose) and mean sitting systolic blood pressure (p<0.001 vs. placebo for each dose). The placebo-corrected reductions in mean sitting systolic/diastolic blood pressure were 5.7/4.0, 5.9/4.5 and 11.2/7.5 mmHg in the aliskiren 75, 150 and 300 mg groups, respectively. After 8 weeks’ treatment, 27.8%, 47.8%, 48.2% and 63.7% of patients in the placebo and aliskiren 75, 150 and 300 mg groups, respectively, achieved a successful treatment response (diastolic blood pressure <90 mmHg and/or reduced by ≥10 mmHg from baseline; p<0.005 vs. placebo for each dose). Aliskiren treatment was well tolerated, with the incidence of adverse events reported in the active treatment groups (53–55%) being similar to that in the placebo group (50%). -

Dosing of ACE-Inhibitors and Arbs

Dosing of ACE-Inhibitors and ARBs Drug Name Starting Dose3 Goal Dose in CKD3 Dosing in renal dysfunction 1,2,4 ACE-Inhibitors Benazepril (Lotensin) 10 mg daily 20-40 mg/d in CrCl < 30 mL/minute or patients taking diuretics, start 5 1-2 divided doses mg/day. Captopril (Capoten) 6.25-25 mg 25-150 mg Reduce initial dose and use smaller increments to titrate three times per day 2 or 3 times per day at 1-2 week intervals. Then, back-titrate to lowest effective dose. CrCl 10—50 ml/min: reduce recommended dose by 25%. CrCl < 10 ml/min: reduce recommended dose by 50%. Removed by hemodialysis; consider giving a dose within 4 hours after dialysis. Diabetic nephropathy (proteinuria >500 mg/day in type 1 diabetics with retinopathy): 25 mg TID Enalapril (Vasotec) 5 mg daily 10-40 mg daily in HTN: Start with 2.5 mg/day if CrCL <= 30 mL/minute; 1-2 divided doses 2.5 mg on dialysis day in hemodialysis patients (dose on non-dialysis days based on BP) CHF: Start with 2.5mg/day under close supervision if serum Na <130 mEq/L or serum Cr>1.6 mg/dL. May titrate at intervals of =>4 days to 2.5 mg BID, then 5 mg BID and higher as needed to maximum of 40 mg/day. Removed by hemodialysis; consider giving a dose within 4 hours after dialysis. Fosinopril (Monopril) 10 mg daily 20-40 mg daily Dosage adjustment not required; biliary excretion increases in renal dysfunction. Start with 5 mg/day QD in patients with CHF and renal dysfunction. -

Renin Inhibition in Hypertension

Journal of the American College of Cardiology Vol. 51, No. 5, 2008 © 2008 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation ISSN 0735-1097/08/$34.00 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.027 STATE-OF-THE-ART PAPER Renin Inhibition in Hypertension Alan H. Gradman, MD, Rishi Kad, MD Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Fifty years ago, investigators identified renin inhibition as the preferred pharmacologic approach to blockade of the renin–angiotensin system. Renin is a monospecific enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the syn- thesis of angiotensin II. Amplified enzymatic activity and additional physiological effects occur when renin and pro-renin bind to the (pro)renin receptor. Until very recently, development of clinically effective renin inhibitors remained elusive. Molecular modeling was used to develop aliskiren, a potent, low-molecular-weight, nonpep- tide, direct renin inhibitor with sufficient bioavailability to produce sustained suppression of plasma renin activity after oral administration. In patients with hypertension, aliskiren produces dose-dependent blood pressure (BP) reduction and 24-h BP control up to a dose of approximately 300 mg once daily; at these doses, aliskiren shows placebo-like tolerability. Its antihypertensive potency is approximately equivalent to that of angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and diuretics. After abrupt withdrawal, persistent BP reduc- tion and prolonged suppression of plasma renin activity is observed. When combined with diuretics, fully additive BP reduction is seen. When given with an angiotensin receptor blocker, aliskiren produces significant additional BP reduction indicative of complimentary pharmacology and more complete renin–angiotensin system block- ade. Clinical trials are currently underway assessing the effects of aliskiren combined with an angiotensin receptor blocker on intermediate markers of end organ damage, and long-term end point trials are planned.