In Search of Mr. Bundin: Henley House 1759 Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on the Basin of Moose River and Adjacent Country Belonging To

REPORT ON THE BASIN OF MOOSE RIVER AND ADJACENT COUNTRY BELONGING TO THE PROVI1TGE QIF OI^TTj^JRXO. By E. B. BORRON, Esq. Stipendiary Magistrate. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. TORONTO: PRINTED BY WARWICK & SONS, 68 AND 70 FRONT STREET WEST. 1890. RE POTT ON THE BASIN OF MOOSE RIVER AND ADJACENT COUNTRY BELONGING TO THE PRCVI1TOE OW OHTABIO. By E. B. BORRO N, Esq.. Stipendiary Magistrate PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY. TORONTO : PRINTED BY WARWICK & SONS, 68 AND 70 FRONT STREET WEST 1890. , — CONTENTS PAGE. Introductory remarks 3 Boundaries and area of Provincial Territory north of the water-parting on the Height-of-Land Plateau 3,4,5 Topography. Naturally divided into three belts 5 ] st, the Southerly or Height-of-Land Plateau 5 2nd, the Intermediate Plateau or Belt 5 3rd, the Northerly or Coast-Belt 5 The fundamental rocks in each 5 Explanations of possible discrepancies in the statements contained in reports for different years in regard of the same or of different sections of the territory 5 Routes followed in lb79 6 Extracts from Report or 1879. Description of the Height-of-Land Flateau from repoit for that year 6 The Northerly or Flat Coast Belt 7 The Intermediate Plateau or Belt 7 James' Bay exceedingly shallow 7 The Albany River and Abittibi, Mattagami and Missinaibi branches of Moose River navigable by boats for some distance in spring 7 Few if any mountains in the two northerly divisions 8 Shallowness of rivers, and slight depth below the general surface of the country 8 Ice jams at or near the mouths of Moose and Albany Rivers 8 Moose Factory, the principal trading post and settlement in the territory 8 Extracts from Reports of 1880. -

Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2019

Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2019 Prepared for the Indigenous Climate Change Gathering 2019 – Ottawa ON March 18-19, 2019 Moose Cree First Nation Overview Moose Factory Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2017-19 Gathering: Process Preparations: Future Q&A Contact info Moose Cree First Nation Moose Factory Est. 1673 Moose Cree First Nation Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2017-2019 Process: We are here Moose Cree First Nation #1 - Initiate • Adaptation Champion and Team. • Band Council support. • Identify stakeholders. Linked Adaptation Plan existing Plans: Moose Factory: • Strategic Plan (2015) • Community Profile (2015) • Organizational Review (2010) Moose Cree First Nation • Values and climate change Impacts • Traditional and Local Knowledge • Regional climate trends and impacts Moose Cree First Nation Understanding Climate Change Impacts Traditional And Local Knowledge Scientific Moose Cree First Nation Gathering the information We took the consultation process to the people One on one interviews with Elders Went to Youth Centre with Pizza Survey Moose Cree First Nation Identified Community Priorities and Impacts become the focus of the Plan Moose Cree First Nation Climate Change - Impacts Traditional Way of Life • Changes in cultural, hunting, trapping, & camping; loss of traditional ways & knowledge. Economy • Changes in hunting & trapping means changes to the subsistence economy. Public Health & Safety • Increased danger when crossing the Moose River. Moose Cree First Nation Climate Change - Impacts Vegetation • Muskeg areas drying & different plant/tree species arriving. Birds • Changes in patterns; New species observed (i.e. Canada geese) & others no longer (i.e. snow geese). Wildlife • Decline in the moose population and small wildlife (i.e. beavers); Increase in new species (i.e. -

Missinaibi River Route

- p. I Me " ,* at. U F. I :: I, I’ uJu -a--- A TRIP TO MOOSE FACTORY. ft - A BACKGROUND INFORMATION UNIT ON THE FUR TRADE OF NORTH EASTERN ONTARIO. 1 I. D. E. PUGH. - -- inabie River Page 18 Northern Times Wednesday,-Septembcr 1, 1971 tilE -e to canoeists OF ASERIES BY D1LfP - the low-lying The Migginabie River pnivenitfi’’ reaches north. marsh and muskeg belt of the udied the Dnlnage j0ttreat in canoe Hudson Bay Lowlands. Flora and fauna this region Is still unorganized. BY thai he is writing a D.E. PUGH strawberries and blueberries of. his education- Lakes are myriad but are only few feet deep. Tributaries spread 0,2. PdW is a unfveni& stud fer delightful wilderness treats River, draining like ant who has shad/ed the amidst the lush growihof Ili:iie;is Is the prin- from the Missinaibi River north. cracks In shattered glass;but the with particular interest ha canoe ferns and wild grasses. The Ca- tjihultary of the muskeg. The routes, fore thesis he is writing noet±t will delight, too,lntbeco To-day it Is the creeks drain nearby river Itself Is wide and shallow, In furthering his education. lourful bright flowers of rnnryh the Moose River martgold, blue iris, -and jose tdsms eaxide- often flowing merely a few Ira- Blotic growth along the Missi- pa- ches deep over wide gravel beds nalbl River reflects the fertile honey suckle and asters. toe pulp and checkerboard-like Amidst this atuzc;-;rt vc-ta The River Is no- which sprout a aiy alluvial banks which are formation of numerous glacier well drained and sheltered. -

A Trip to Moose Factory. a Background Information

- p. I Me " ,* at. U F. I :: I, I’ uJu -a--- A TRIP TO MOOSE FACTORY. ft - A BACKGROUND INFORMATION UNIT ON THE FUR TRADE OF NORTH EASTERN ONTARIO. 1 I. D. E. PUGH. - -- inabie River Page 18 Northern Times Wednesday,-Septembcr 1, 1971 tilE -e to canoeists OF ASERIES BY D1LfP - the low-lying The Migginabie River pnivenitfi’’ reaches north. marsh and muskeg belt of the udied the Dnlnage j0ttreat in canoe Hudson Bay Lowlands. Flora and fauna this region Is still unorganized. BY thai he is writing a D.E. PUGH strawberries and blueberries of. his education- Lakes are myriad but are only few feet deep. Tributaries spread 0,2. PdW is a unfveni& stud fer delightful wilderness treats River, draining like ant who has shad/ed the amidst the lush growihof Ili:iie;is Is the prin- from the Missinaibi River north. cracks In shattered glass;but the with particular interest ha canoe ferns and wild grasses. The Ca- tjihultary of the muskeg. The routes, fore thesis he is writing noet±t will delight, too,lntbeco To-day it Is the creeks drain nearby river Itself Is wide and shallow, In furthering his education. lourful bright flowers of rnnryh the Moose River martgold, blue iris, -and jose tdsms eaxide- often flowing merely a few Ira- Blotic growth along the Missi- pa- ches deep over wide gravel beds nalbl River reflects the fertile honey suckle and asters. toe pulp and checkerboard-like Amidst this atuzc;-;rt vc-ta The River Is no- which sprout a aiy alluvial banks which are formation of numerous glacier well drained and sheltered. -

Canada 25: Southern James Bay Migratory Bird Sanctuaries, Ontario and Nunavut

CANADA 25: SOUTHERN JAMES BAY MIGRATORY BIRD SANCTUARIES, ONTARIO AND NUNAVUT Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Effective Date of Information: The information provided is taken from text supplied at the time of designation to the List of Wetlands of International Importance, May 1987 and updated by the Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region in October 2001. Reference: 25th Ramsar site designated in Canada. Name and Address of Compiler: Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, 49 Camelot Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1A. Date of Ramsar Designation: 27 May 1987. Geographical Coordinates: Two areas: Hannah Bay Bird Sanctuary - 51°20'N., 79°31'W; and Moose River Bird Sanctuary - 51°20'N., 80°25'W. General Location: The two sanctuaries are located in southern James Bay. Hannah Bay Bird Sanctuary lies on the eastern side of Hannah Bay, the southernmost project of James Bay, from the Little Mississicabi River to East Point. Moose River Bird Sanctuary lies at the mouth of the Moose River and comprises Ship Sands Island and a piece of land on the eastern flats of the river mouth. The first sanctuary is located 60 km east of Moosonee and the second 18 km to the north-east. Both are located in the Province of Ontario. Offshore waters lie in the Nunavut Territory. Area: 25 290 ha (Hannah Bay Bird Sanctuary 23 830 ha; Moose River Bird Sanctuary 1 460 ha). Wetland Type (Ramsar Classification System): Marine and coastal wetlands: Type A - marine waters; Type G - intertidal mud, sand, and salt flats; Type F - estuarine waters; Type H - intertidal marshes. Inland wetlands: Type Tp - permanent freshwater ponds, marshes and swamps; Type W - shrub swamps; Type Xp - forested peatlands. -

“Moose Factory Is My Home”: Mocreebec's Struggle for Recognition and Self-Determination

“Moose Factory Is My Home”: MoCreebec’s Struggle for Recognition and Self-Determination A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of the Masters of Arts in Anthropology In the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology By Kota Kimura Copyright Kota Kimura, May 2016. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this the- sis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is under- stood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i Abstract This thesis, based on my ethnographic research in Moose Factory, Ontario documents the his- tory of MoCreebec people from the early Twentieth Century to the present. -

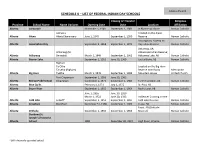

Schedule K – List of Federal Indian Day Schools

SCHEDULE K – LIST OF FEDERAL INDIAN DAY SCHOOLS Closing or Transfer Religious Province School Name Name Variants Opening Date Date Location Affiliation Alberta Alexander November 1, 1949 September 1, 1981 In Riviere qui Barre Roman Catholic Glenevis Located on the Alexis Alberta Alexis Alexis Elementary June 1, 1949 September 1, 1990 Reserve Roman Catholic Assumption, Alberta on Alberta Assumption Day September 9, 1968 September 1, 1971 Hay Lakes Reserve Roman Catholic Atikameg, AB; Atikameg (St. Atikamisie Indian Reserve; Alberta Atikameg Benedict) March 1, 1949 September 1, 1962 Atikameg Lake, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Beaver Lake September 1, 1952 June 30, 1960 Lac La Biche, AB Roman Catholic Bighorn Ta Otha Located on the Big Horn Ta Otha (Bighorn) Reserve near Rocky Mennonite Alberta Big Horn Taotha March 1, 1949 September 1, 1989 Mountain House United Church Fort Chipewyan September 1, 1956 June 30, 1963 Alberta Bishop Piché School Chipewyan September 1, 1971 September 1, 1985 Fort Chipewyan, AB Roman Catholic Alberta Blue Quills February 1, 1971 July 1, 1972 St. Paul, AB Alberta Boyer River September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Rocky Lane, AB Roman Catholic June 1, 1916 June 30, 1920 March 1, 1922 June 30, 1933 At Beaver Crossing on the Alberta Cold Lake LeGoff1 September 1, 1953 September 1, 1997 Cold Lake Reserve Roman Catholic Alberta Crowfoot Blackfoot December 31, 1968 September 1, 1989 Cluny, AB Roman Catholic Faust, AB (Driftpile Alberta Driftpile September 1, 1955 September 1, 1964 Reserve) Roman Catholic Dunbow (St. Joseph’s) Industrial Alberta School 1884 December 30, 1922 High River, Alberta Roman Catholic 1 Still a federally-operated school. -

Ontario Bird Records Committee Report for 1990 by Robert Curry

18 editor of American Birds and the Editors' Note: The Ontario Bird OBRC, so that such incongruities Records Committee, not Ontario don't continue. Considering the much Birds, adjudicates rare bird records in larger readership of American Birds Ontario and determines which birds (now in its new, hideous, and are to be reported. Consequently, Mr. glamorized version), one must ask Holdsworth's suggestions for changes which organ represents the final say in reporting policy are more considering Ontario bird records? appropriately directed to the OBRC Surely, it is the OBRC, but the However, the Editors recognize a readers of American Birds hear not of growing interest in "recognizable the OBRC's decisions concerning forms" among Ontario birders, and as records in AB. A union of sorts a result, have instituted a new feature between these two journals would on this subject. See page 49 in this prevent such major discrepancies and issue for a checklist. give North American birders an authoritative view of Ontario bird records. James Holdsworth Woodstock, Ontario Ontario Bird Records Committee Report for 1990 by Robert Curry This is the ninth annual report of the Roberson (1990) indicated that we are Ontario Bird Records Committee following the same procedures as (OBRCI of the Ontario Field similar groups across North America Ornithologists. Published herein are and elsewhere. Unfortunately, there the records that were received and remain certain portions of the reviewed by the Committee during province from which very few 1990. In total, 187 records were submissions are received despite assessed, the identification of which requests for existing reports of review 165 (about 88%1 were found to be list species. -

2014 Ontario Fishing Regulations Summary

ZONE 8 42 James Bay Recreational FishingRegulations 2014 Moosonee Key Plan River Moose River 3 Provincial Boundary FISHERIES MANAGEMENTZONE8 Kesagami River Lake Missinaibi River 11 Hearst Mattice 652 634 Railway Kapuskasing NOTE: Kabinakagami Cochrane - Those portions of the Missinaibi River Lake and Moose River that are between Zone 3 631 and Zone 8 are wholly within Zone 8 7 Railway 8 Lake 11 655 Iroquois Falls Abitibi Chapleau Crown Provincial Boundary Legend Timmins South Porcupine City/Town/Community Missinaibi Night MNR District Office Hawk 17 Major Road 101 L. Kirkland Lake Major Railway Game Preserve Wawa Zone Boundary 101 66 144 Major Lake Chapleau Park or Crown Game Preserve Elk Lake Lake Superior 129 Gogama Lake Sturgeon - Sultan 560 65 Closed All Year 9 667 Lake Sultan New Liskeard Timiskaming Industrial Rd 560 129 Lake Superior Lady-Evelyn Haileybury 0 20 40 60 80 100 Smoothwater 10 11 12 km ZONE 8 SEASONS AND LIMITS SPECIES OPEN SEASONS LIMITS SPECIES OPEN SEASONS LIMITS Walleye & Jan. 1 to Apr. 14 S - 4; not more than 1 greater than Sunfish Open all year S - 50 Sauger or any & 3rd Sat. in 46 cm (18.1 in.) C - 25 combination May to Dec. 31 C - 2; not more than 1 greater than 46 cm (18.1 in.) Brook Trout* Jan. 1 to Sept. 15 S - 5 C - 2 Largemouth Open all year S - 6 & Smallmouth C - 2 Rainbow Open all year S - 5 Bass or any Trout* C - 2 combination Lake Trout* Feb. 15 to Mar. 15 S - 3 Northern Pike Open all year S - 6; not more than 2 greater than & 3rd Sat. -

MOOSE CREE FIRST NATION's SPEAKING NOTES ON

MOOSE CREE FIRST NATION’s SPEAKING NOTES ON PROTECTED AREAS TO THE FEDERAL STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT For presentation on October 18, 2016 Chief Patricia Faries Jack Rickard, Director of Lands and Resources ([email protected]) Introduction: Good afternoon, Thank you for this opportunity to share with the Committee our perspective on protected areas and conservation objectives. Also, I would like to acknowledge the traditional territory of the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan. It is an honour to come before you and share our thoughts as Indigenous People. My name is Patricia Faries and I am joined by our Director of Lands and Resources Jack Rickard. We are from the Moose Cree First Nation and we have recently made our reaffirmation of our Homelands Declaration on September 27, 2016. Our home community is located on Moose Factory Island within the Moose River Delta. Our Moose Cree Homelands extend from Hearst, Ontario in the west just beyond the Quebec border in the east, and from south of Highway 11 to points north toward the Albany River. “Homelands” are the areas that are determined by the MCFN citizens (Eh- lilu-wuk) which is inclusive generally of the historical occupancy and use of lands and watersheds in the Northeastern Ontario. The Moose Cree Homelands is comprised of static boundaries and covers approximately 60,000 sq. km. As the Moose Cree have determined, Homelands include surface and subsurface lands, water and air. The Homeland areas have been derived using Moose Cree Knowledge from our Elders and are based on continued presence of hunting, trapping and harvest grounds prior to the Ontario government trapline system existed. -

OFO Bird Finding Guide #6

32 OFO Bird Finding Guide #6 A Birder's Guide to Southern James Bay, Including Moosonee and Moose Factory Stephen 1. Scholten Introduction in the region. This guide is intended to introduce Birding this area most effec experienced birders and naturalists, tively requires coverage of the as well as casual visitors, to the bird range of habitats found near the vil ing opportunities available in the lages, as well as on the coast. southern James Bay area. It pro Walking the townsites of Moosonee vides directions to, and descriptions and Moose Factory will yield birds of, different locations and habitats of disturbed habitats, willow thick that may be of interest to birders ets' shorelines, upland spruce and and naturalists. It also describes poplar woods, and freshwater some of the trail systems which, marshes. A trip to the coast, either though not intended for birding, for a day to Shipsands Island or offer easily accessible walks White Top, or for several days of through a variety of habitats in the camping at a more distant site, will area. The main attractions of the offer more extensive freshwater Moosonee area to birders are the marshes, as well as brackish and salt wide diversity of habitats, many of marshes, the open waters and van which are uncommon or non-exis tage points of James Bay, and tent in other parts of the province, potentially large numbers of and the relatively easy access con migrants associated with these sidering the northern location. habitats. If your visit coincides with Habitat types include boreal forest spring or fall migration, you can on coastal beach ridges and well expect large numbers of sparrows, drained river banks, bogs and fens warblers and finches in the dis in the lowland interior, coastal habi turbed habitats, thickets and wood tats such as freshwater and salt lands, and large numbers of shore marsh, mud flats, and ponds. -

The Institutions Listed on the Following Pages Have Been Requested to Be

The institutions listed on the following pages have been requested to be added to the list of Indian residential schools recognized by the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. These requested institutions have been researched by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada and assessed against the test in Article 12 of the Settlement Agreement for determining whether the institutions should be considered an Indian residential school. The decision about whether the institution will or will not be included in the Settlement Agreement is set out on the following pages, as well as the brief reason for the decision. If no decision is set out on the following pages, the institution is currently under review. Please note that, although a decision may have already been made with respect to a certain institution, you are entitled to submit a further request for that institution. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada will revisit its decision on a particular institution based on any new information or supporting documentation you are able to provide. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada will respond to all requests directly to the requestor in writing. In order for an institution to be added to the settlement, Article 12 of the Settlement Agreement requires that the institution satisfies both parts of the following two-part test: (i) The child must have been placed in a residence away from the family home by or under the authority of Canada for the purpose of education; and (ii) Canada must have been jointly or solely responsible for the operation of the residence and care of the children resident there (e.g.