Decline of a Cosmopolitanism City?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representation of Sikh Character in Bollywood Movies:A Study on Selective Bollywood Movies

PJAEE, 17(6) (2020) REPRESENTATION OF SIKH CHARACTER IN BOLLYWOOD MOVIES:A STUDY ON SELECTIVE BOLLYWOOD MOVIES Navpreet Kaur Assistant Professor University Institute of Media Studies, Chandigarh University, Punjab, India [email protected] Navpreet Kaur, Representation Of Sikh Character In Bollywood Movies: A Study On Selective Bollywood Movies– Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17(6) (2020), ISSN 1567-214X. Keywords: Bollywood, Sikh, Sikh Character, War, Drama, Crime, Biopic, Action, Diljit Dosanhj, Punjab Abstract Sikhs have been ordinarily spoken to in mainstream Hindi film either as courageous warriors or as classless rustics. In the patriot message in which the envisioned was an urban North Indian, Hindu male, Sikh characters were uprooted and made to give entertainment. Bollywood stars have donned the turban to turn Sikh cool, Sikhs view the representation of the community in Bollywood as demeaning and have attempted to revive the Punjabi film industry as an attempt at authentic self-representation. But with the passage of time the Bollywood makers experimented with the role and images of Sikh character. Sunny Deol's starrer movie Border and Gadar led a foundation of Sikh identity and real image of Sikh community and open the doors for others. This paper examines representation of Sikhs in new Bollywood films to inquire if the romanticization of Sikhs as representing rustic authenticity is a clever marketing tactic used by the Bollywood. Introduction Bollywood is the sobriquet for India's Hindi language film industry, situated in the city of Mumbai, Maharashtra. It is all the more officially alluded to as Hindi film. The expression "Bollywood" is frequently utilized by non-Indians as a synecdoche to allude to the entire of Indian film; be that as it may, Bollywood legitimate is just a piece of the bigger Indian film industry, which incorporates other creation communities delivering films in numerous other Indian dialects. -

Paper 2 Practice of Advertising Lesson 1

PAPER 2 PRACTICE OF ADVERTISING LESSON 1 Newspaper, Magazine LESSON 2 Radio, Doordarshan LESSON 3 Film and Miscellaneous Media LESSON 4 Poster, Banner, Hoarding, Wall Writing, and Transit Media LESSON 5 Characteristics of Media LESSON 6 Internet Advertising LESSON 7 Layout and Design LESSON 8 Creativity in Advertising LESSON 9 Layout and Designing of Advertisement for Journal and Magazine LESSON 10 Cartoon and Graphics LESSON 11 Advertising Campaign LESSON 12 Media Planning Course Code : 02 Author: Prof Pradeep Mathur Lesson-1 NEWSPAPER, MAGAZINE STRUCTURE:- 1.1 Objective 1.2 Introduction 1.3 Advertising Definition Background and History 1.4 Newspaper Printed media Growth and variety Advantages of newspaper Disadvantages of newspapers Future of newspapers 1.5 Magazine Magazine as an advertising medium Types of magazine Cost of production of magazine Advantages of magazine Disadvantages of magazines Future of magazines 1.6 Summary 1.7 Keywords 1.8 Questions for practice 1.9 Suggested readings 1.1 Objectives The aim of this lesson is to project newspaper and magazine as advertising medium. In print medium they are most commonly. After going through this lesson you will be able to: Describe and understand the print media scence in the country. Identify the potent tools for advertising in print media. Understand the role of these media in social developments. Compare both of them and know which one to use and when. Indicate the future prospects of the print media. 1.2 Introduction Advertising media consists of any means by which sales can be conveyed to potential buyers. The choices of media is immense in the developed countries but somewhat limited in the developing countries. -

Internationales Filmfestival Karlovy Vary

Internationales Filmfestival Karlovy Vary Das Internationale Filmfestival Karlovy Vary (tschechisch Mezinárodní filmový festival Karlovy Vary, englische Kurzform KVIFF) findet jedes Jahr Anfang Juli im böhmischen Kurort Karlsbad statt. Das KVIFF zählt zu den 13 A-Festivals, gehört in dieser Gruppe der weltweit führenden Festivals allerdings zu den kleineren Veranstaltungen. Gemessen an der Zahl der verkauften Tickets (etwa 130.000) liegt es zwischen dem etwas größeren Festival von Locarno (147.000) und dem kleineren Warschauer Festival (108.000). Inhaltsverzeichnis Logo des Festivals Geschichte Preisträger Siehe auch Weblinks Einzelnachweise Geschichte 41. Internationales Filmfestival in Das Filmfestival in Karlsbad ist eine der ältesten Filmschauen der Welt. Karlsbad, 2006 Premiere feierte es 1946, wobei es im ersten Jahr mit Marienbad einen zweiten Austragungsort gab. In den drei folgenden Jahren fand das Festival sogar ausschließlich in Marienbad statt, ab 1950 dann nur noch in Karlsbad. Die ersten Preise wurden 1948 verliehen. Damit blicken nur die Filmfestspiele von Venedig und das Moskauer Filmfestival, die bereits in den 1930er Jahren begründet wurden, auf eine längere Tradition zurück. Die Filmfestspiele von Cannes und das Festival von Locarno wurden ebenfalls erstmals 1946 veranstaltet, beide allerdings einige Wochen nach dem ersten Karlsbader Festival. Von 1958 bis 1992 fand das Filmfestival Karlovy Vary lediglich alle zwei Jahre – im Wechsel mit dem Moskauer Filmfestival – statt. Aus diesem Grund konnte das Festival im Jahr 2015 erst seine 50. Austragung feiern, obwohl es zu dem Zeitpunkt bereits 69 Jahre existierte.[1] Zu größeren Veränderungen kam es schließlich bei der 29. Auflage des Festivals im Jahr 1994, als auf einen jährlichen Austragungsrhythmus umgestellt wurde. Zuvor hatten das tschechische Kultusministerium, die Stadt Karlsbad und das ortsansässige Grand-Hotel Pupp eine Stiftung für das Festival gegründet, die den bekannten tschechischen Schauspieler Jiří Bartoška als Präsidenten des Festivals engagierte. -

Circular-21St-Dec10.Pdf

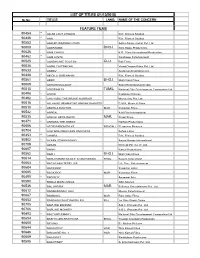

LIST OF TITLES (21/12/2010) SL.No. TITLES LANG. NAME OF THE CONCERN FEATURE FILMS 90454 * AA AB LAUT CHALEN R.K. Films & Studios 90446 * AAH R.K. Films & Studios 90553 AAKHRI WARNING (DUB) Aditya Music (India) Pvt. Ltd. 90608 AAKRAMAK BHOJ. N.N. Sippy Productions 90626 AAM CHHOO K.R. Films International Production 90462 * AAM JUNTA Southpaw Entertainment 90525 AANDHI ANE TOOFAN GUJ. Pali Films 90638 AAPKI CHITTHIYAN Vinod Chopra Films Pvt. Ltd. 90633 AARAV Andaman Entertainment 90448 * AB DILLI DUR NAHIN R.K. Films & Studios 90561 ABER BHOJ. Malti Vidur Films 90669 ADHURI MULAKAT Silent Entertainment India 90515 ADIGRAM 79 TAMIL National Film Development Corporation Ltd. 90498 * ADIOS E-Motion Pictures 90492 * AHILYABAI THE BRAVE WARRIOR Morya Arts Pvt. Ltd. 90618 ALLAH KE REHMAT KE ANWAR BARASTE HAIN C.M.K. Music & Films 90510 * ANDHLA DOCTOR MAR. Yugantar Films 90542 APPEAL A M Film International 90535 ASHI HI HERA PHERI MAR. Prapti Films 90471 * ASHOKA THE GREAT Ralhan Productions 90686 ATOR PAROMITA KE BENGALI Response Pictures 90704 AUR WOH SHAITAAN BAN GAYA Ashok Films 90453 * AWARA R.K. Films & Studios 90502 * AZAAN (SURRENDER) Aarya Movies International 90709 AZAAN Percept Pic. Co. P. Ltd. 90607 BABRI Rahul Productions 90562 BABU BHOJ. Malti Vidur Films 90614 BABU HAMAR MUGLE AZAM HAWAN BHOJ. Kusum Cine Vision 90664 BACHCHAN TERE LIYE Life Time Entertainment 90684 BACK DOC Yugantar Films 90685 BACK DOC MAR. Yugantar Films 90490 * BAD BOY Anupreet Arts 90590 BADLA MAIN LUNGA ABC Movies 90536 BAL SHIVBA MAR. E-Sense Entertainment Pvt. Ltd. 90612 BANARASWALI GALI Moosa Entertainment 90667 BANDGUL MAR. -

Raj Kapoor, Dev Anand and Dilip Kumar by Chandrakant Trivedi Trimurti Is Always an Interesting and Inspiring Topic

Federation of Indian Associations (FIA) Sunday / December 20, 2020 Federation of Indian Associations NY-NJ-CT. 501(C)3 The Largest Non-Profit Grassroot Umbrella Organization in the Tri-state of NY-NJ-CT Sunday / December 20, 2020 Issue: 25 100% VOLUNTEER RUN ORGANIZATION EST. 1970 FIA Hosts India Visa and OCI Deconstructing Christmas, Indian Rapper DIVINE Town Hall to Aid Community to a Supreme Religious and of ‘Gully Boy’ Fame Better Understand Working of Social Mega Celebration Featured on Times New Visa Outsourcing Agency Worldwide Square Billboard FIA Hosts India Visa and OCI Town Hall to Aid Community to Better Understand Working of New Visa Outsourcing Agency Record number of people attend one-of-a-kind event with Consul General of India in New York and his staff The Federation of Indian Associations of New York, Randhir Jaiswal, Deputy Consul General, the tristate area of New York, New Jersey and Shatrughna Sinha, and Consul, consular, passport Connecticut (FIA-Tristate) hosted a virtual Town and visa division, Murugesan Ramaswamy. Hall on India Visa and OCI (Overseas Citizenship In the first segment of the Town Hall, Consul of India) card, on Dec. 7. The first of its kind event General Jaiswal and his staff answered collectively aimed to expand the community’s understanding compiled questions regarding the transition process of the workings of the new agency, VFS Global, as from the previous processing agency to VFS Global; well as the details about the transition from the old and its impact on the Indian American community. agency, CKGS, to the new agency, VFS Global. -

Hindi 1509 Song

NO. SONG TITLE MOVIE/ALBUM VERSION HINDI 1509 SONG NO. SONG TITLE MOVIE/ALBUM VERSION 03900 AA AA BHI JA TEESRI KASAM LATA MANGESHKAR JIS DESH MEIN 03901 AA AB LAUT CHALE GANGA BEHTI HAI MUKESH, LATA MANGESHKAR DOOR GAGAN KI 03002 AA CHAL KE TUJHE CHHAON MEIN KISHORE KUMAR 03902 AA DIL SE DIL MILA LE NAVRANG ASHA BHOSLE 03903 AA GALE LAG JA APRIL FOOL MOHD. RAFI 03904 AA JAANEJAAN INTEQAM LATA MANGESHKAR 03905 AA JAO TADAPTE HAI AAWAARA LATA MANGESHKAR 03906 AA MERE HUMJOLI AA JEENE KI RAAH LATA, MOHD. RAFI 03907 AA MERI JAAN CHANDNI LATA MANGESHKAR 03908 AADAMI ZINDAGI VISHWATMA MOHD. AZIZ 03005 AADHA HAI CHANDRAMA NAVRANG MAHENDRA, ASHA BHOSLE 03909 AADMI MUSAFIR HAI APNAPAN LATA, MOHD. RAFI 03910 AAGE BHI JAANE NA TU WAQT ASHA BHOSLE 03007 AAH KO CHAHIYE MIRZA GAALIB JAGJEET SINGH 03911 AAHA AYEE MILAN KI BELA AYEE MILAN KI BELA ASHA, MOHD. RAFI 03912 AAI AAI YA SOOKU SOOKU JUNGLEE MOHD. RAFI 03913 AAINA BATA KAISE MOHABBAT SONU NIGAM, VINOD 03914 AAJ HAI DO OCTOBER KA DIN PARIVAR LATA MANGESHKAR 03009 AAJ KAL PAANV ZAMEEN PAR GHAR LATA MANGESHKAR 03915 AAJ KI RAAT PIYA BAAZI GEETA DUTT 03916 AAJ KI SHAAM TAWAIF ASHA BHOSLE AAJ MADAHOSH HUA JAAYE RE LATA MANGESHKAR, 03917 SHARMILEE KISHORE KUMAR 03918 AAJ MAIN JAWAAN HO GAYI HOON MAIN SUNDAR HOON LATA MANGESHKAR 03012 AAJ MAUSAM BADA BEIMAAN HAI LOAFER MOHD. RAFI 03013 AAJ MERE MAAN MAIN SAKHI AAN LATA MANGESHKAR 03014 AAJ MERE YAAR KI SHAADI HAI AADMI SADAK KA MOHD. RAFI 03919 AAJ NA CHHODENGE KATI PATANG KISHORE KUMAR, LATA A HINDI 1509 SONGS | 01 VER.100 NO. -

No End to Crimes Against Dalits

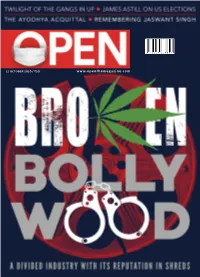

www.openthemagazine.com 50 12 OCTOBER /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 40 12 OCTOBER 2020 CONTENTS 12 OCTOBER 2020 5 6 8 14 16 18 22 28 LOCOMOTIF INDRAPRASTHA MUMBAI TOUCHSTONE SOFT POWER WHISPERER IN MEMORIAM OPEN ESSAY The House of By Virendra Kapoor NOTEBOOK The sounds of our The Swami and the By Jayanta Ghosal Jaswant Singh Is it really over Jaswant Singh By Anil Dharker discontents Himalayas (1938-2020) for Trump? By S Prasannarajan By Keerthik Sasidharan By Makarand R Paranjape By MJ Akbar By James Astill and TCA Raghavan 32 32 BROKEN BOLLYWOOD Divided, self-referential in its storytelling, all too keen to celebrate mediocrity, its reputation in tatters and work largely stalled, the Mumbai film industry has hit rock bottom By Kaveree Bamzai 40 GRASS ROOTS Marijuana was not considered a social evil in the past and its return to respectability is inevitable in India By Madhavankutty Pillai 44 THE TWILIGHT OF THE GANGS 40 Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has declared war on organised crime By Virendra Nath Bhatt 22 50 STATECRAFT Madhya Pradesh’s Covid opportunity By Ullekh NP 44 54 GLITTER IN GLOOM The gold loan market is cashing in on the pandemic By Nikita Doval 50 58 62 64 66 BETWEEN BODIES AND BELONGING MIND AND MACHINE THE JAISHANKAR DOCTRINE NOT PEOPLE LIKE US A group exhibition imagines Novels that intertwine artificial Rethinking India’s engagement Act two a multiplicity of futures intelligence with ethics with its enemies and friends By Rajeev Masand By Rosalyn D’Mello By Arnav Das Sharma By Siddharth Singh Cover by Saurabh Singh 12 OCTOBER 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 3 OPEN MAIL [email protected] EDITOR S Prasannarajan LETTER OF THE WEEK MANAGING EDITOR PR Ramesh C EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ullekh NP By any criterion, 2020 is annus horribilis (‘Covid-19: The EDITOR-AT-LARGE Siddharth Singh DEPUTY EDITORS Madhavankutty Pillai Surge’, October 5th, 2020). -

LIST of HINDI CINEMA AS on 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days

LIST OF HINDI CINEMA AS ON 17.10.2017 1 Title : 100 Days/ Directed by- Partho Ghosh Class No : 100 HFC Accn No. : FC003137 Location : gsl 2 Title : 15 Park Avenue Class No : FIF HFC Accn No. : FC001288 Location : gsl 3 Title : 1947 Earth Class No : EAR HFC Accn No. : FC001859 Location : gsl 4 Title : 27 Down Class No : TWD HFC Accn No. : FC003381 Location : gsl 5 Title : 3 Bachelors Class No : THR(3) HFC Accn No. : FC003337 Location : gsl 6 Title : 3 Idiots Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC001999 Location : gsl 7 Title : 36 China Town Mn.Entr. : Mustan, Abbas Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001100 Location : gsl 8 Title : 36 Chowringhee Lane Class No : THI HFC Accn No. : FC001264 Location : gsl 9 Title : 3G ( three G):a killer connection Class No : THR HFC Accn No. : FC003469 Location : gsl 10 Title : 7 khoon maaf/ Vishal Bharadwaj Film Class No : SAA HFC Accn No. : FC002198 Location : gsl 11 Title : 8 x 10 Tasveer / a film by Nagesh Kukunoor: Eight into ten tasveer Class No : EIG HFC Accn No. : FC002638 Location : gsl 12 Title : Aadmi aur Insaan / .R. Chopra film Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002409 Location : gsl 13 Title : Aadmi / Dir. A. Bhimsingh Class No : AAD HFC Accn No. : FC002640 Location : gsl 14 Title : Aag Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC001678 Location : gsl 15 Title : Aag Mn.Entr. : Raj Kapoor Class No : AAG HFC Accn No. : FC000105 Location : MSR 16 Title : Aaj aur kal / Dir. by Vasant Jogalekar Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No. : FC002641 Location : gsl 17 Title : Aaja Nachle Class No : AAJ HFC Accn No. -

Deepa Mehta's Elemental Trilogy and the Depiction of Indian Culture In

Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy and the Depiction of Indian Culture in Select Filmic Adaptations A Thesis Submitted to For the award of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH Submitted by: Supervised by: Ishfaq Ahmad Tramboo Dr. Nipun Chaudhary Reg. No. 11512772 Assistant Professor Department of English LOVELY FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND ARTS LOVELY PROFESSIONAL UNIVERSITY PHAGWARA-144411 (PUNJAB) 2019 Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis entitles Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy and The Depiction of Indian Culture in Select Filmic Adaptations submitted for the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my original work. All the ideas and references are duly acknowledged. It does not contain any other work for the award of any other degree or diploma at any university or institution. I hereby confirm that I have carefully checked the final version of printed and softcopy of the thesis for the completeness and for the incorporation of all the valuable suggestions of Doctoral Board of the University. I hereby submit the final version of the printed copy of my thesis as per the guidelines and the exact same content in CD as a separate PDF file to be uploaded in Shodhganga. Place: Phagwara Ishfaq Ahmad Tramboo Date: 31 July 2019 (11512772) ii Certificate By Advisor I hereby affirm as under that: 1) The thesis presented by Ishfaq Ahmad Tramboo entitled “Deepa Mehta’s Elemental Trilogy and The Depiction of Indian Culture in Select Filmic Adaptations” is worthy of consideration for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Hindi1512 (Et19khnd)

AceKaraoke.com ET-19KH Song List No. SONG TITLE MOVIE/ALBUM SINGER 20001 AA AA BHI JA TEESRI KASAM LATA MANGESHKAR 20002 AA AB LAUT CHALE JIS DESH MEIN GANGA BEHTI HAI MUKESH, LATA 20003 AA CHAL KE TUJHE DOOR GAGAN KI CHHAON MEIN KISHOE KUMAR 20004 AA DIL SE DIL MILA LE NAVRANG ASHA BHOSLE 20005 AA GALE LAG JA APRIL FOOL MOHD. RAFI 20006 AA JAANEJAAN INTEQAM LATA MANGESHKAR 20007 AA JAO TADAPTE HAI AAWAARA LATA MANGESHKAR 20008 AA MERE HUMJOLI AA JEENE KI RAAH LATA, MOHD. RAFI 20009 AA MERI JAAN CHANDNI LATA MANGESHKAR 20010 AADAMI ZINDAGI VISHWATMA MOHD. AZIZ 20011 AADHA HAI CHANDRAMA NAVRANG MAHENDRA & ASHA BHOSLE 20012 AADMI MUSAFIR HAI APNAPAN LATA, MOHD. RAFI 20013 AAGE BHI JAANE NA TU WAQT ASHA BHOSLE 20014 AAH KO CHAHIYE MIRZA GAALIB JAGJEET SINGH 20015 AAHA AYEE MILAN KI BELA AYEE MILAN KI BELA ASHA, MOHD. RAFI 20016 AAI AAI YA SOOKU SOOKU JUNGLEE MOHD. RAFI 20017 AAINA BATA KAISE MOHABBAT SONU NIGAM, VINOD 20018 AAJ HAI DO OCTOBER KA DIN PARIVAR LATA MANGESHKAR 20019 AAJ KAL PAANV ZAMEEN PAR GHAR LATA MANGESHKAR 20020 AAJ KI RAAT PIYA BAAZI GEETA DUTT 20021 AAJ KI SHAAM TAWAIF ASHA BHOSLE 20022 AAJ MADAHOSH HUA JAAYE RE SHARMILEE LATA, KISHORE 20023 AAJ MAIN JAWAAN HO GAYI HOON MAIN SUNDAR HOON LATA MANGESHKAR 20024 AAJ MAUSAM BADA BEIMAAN HAI LOAFER MOHD. RAFI 20025 AAJ MERE MAAN MAIN SAKHI AAN LATA MANGESHKAR 20026 AAJ MERE YAAR KI SHAADI HAI AADMI SADAK KA MOHD.RAFI 20027 AAJ NA CHHODENGE KATI PATANG KISHORE KUMAR, LATA 20028 AAJ PHIR JEENE KI GUIDE LATA MANGESHKAR 20029 AAJ PURANI RAAHON SE AADMI MOHD. -

INDIAN YOUTH CULTURE REFLECTIONS on FILM an EAA Interview with Coonoor Kripalani

Teaching About Asia Through Youth Culture INDIAN YOUTH CULTURE REFLECTIONS ON FILM An EAA Interview with Coonoor Kripalani Coonoor Kripalani is Honorary Research Fellow at the Centre of Asian Studies (CAS), the University of Hong Kong. She wrote her thesis on a comparison of Gandhi and Mao and maintains a keen interest in current de- velopments in India, China, and Southeast Asia. Cur- rently based in Singapore, she conducts research and writes on popular Hindi film, as well as radio broad- casting in India. Her articles on films include topics such as terrorism, in-film advertising, and marriage and fam- ily. In addition to her work on film, Kripalani has de- veloped a series of four Hindi books for preschool children, and bilingual editions were published in 2007 by the Global Indian Foundation (Singapore). In the interview that follows, Kripalani provides readers with both a good ntroduction to Indian film and specific information about the changing tastes of Indian youth. Lucien: ank you for this interview, Coonoor. Readers have enjoyed your articles on Indian films in past In the 1960s and 70s, issues of EAA. Would you please briefly tell us a little about your background and how you became interested in cinema? popular Hindi film Coonoor Kripalani: I worked at the Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong for a number of years. My field is history, and while in Hong Kong, I wrote my Master’s of Philosophy thesis on a com- was viewed snob- parison of Gandhi and Mao. Living overseas, I did not see a Hindi film for many years until the mid-1990s. -

ACMI Annual Report 2011/12

ANNUAL REPORT 2011/12 CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 3 HIGHLIGHTS 4 FROM THE PRESIDENT AND DIRectoR 6 EXHIBITIONS 10 FILM 16 PUBLIC PROGRAMS AND EDUCATION 25 ONLINE, OUTREACH AND RESOURCES 29 MORE ABOUT US 38 PERFORMANCE SUMMARY 40 ADMINISTRATIVE REPORTING REQUIREMENTS 50 DISCLOSURE INDEX 52 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS COVER IMAGE: SHAUN GLADWELL, Parallel Forces, 2011, COURtESy tHE ARtISt AND ANNA Schwartz GALLERy INTRODUCTION OUR AIMS Cultural Leadership: To engage the widest audiences and communities of interest, enabling them to At the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), experience and explore excellence and new we’re in the business of creativity, ideas, innovation and perspectives in the moving image. magic. Creativity and Learning: To foster talent, creative As the truly universal art form, the moving image skills, personal expression, formal and informal literally surrounds us, capturing the moments, learning in screen literacy, and promote its progress milestones and memories that define who we are. in educational practice. Through a vibrant array of film programs, major exhibitions, live events, creative workshops and public Innovation Catalyst: To promote experimentation in and education programs, ACMI delivers audiences an screen content, and act as a catalyst for innovation unsurpassed diversity of ways to engage with the in digital culture, through creative-industry collaborations and professional networks. moving image. Knowledge and Collections: To collect, research and A major Australian cultural agency located at Federation make accessible screen heritage and social Square, ACMI remains the world’s first cultural centre memories, generating critical appreciation of the dedicated to the moving image in all its forms. Since field, its impacts and evolving directions.