Spring/Summer 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

Wilderness Visitors and Recreation Impacts: Baseline Data Available for Twentieth Century Conditions

United States Department of Agriculture Wilderness Visitors and Forest Service Recreation Impacts: Baseline Rocky Mountain Research Station Data Available for Twentieth General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-117 Century Conditions September 2003 David N. Cole Vita Wright Abstract __________________________________________ Cole, David N.; Wright, Vita. 2003. Wilderness visitors and recreation impacts: baseline data available for twentieth century conditions. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-117. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 52 p. This report provides an assessment and compilation of recreation-related monitoring data sources across the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). Telephone interviews with managers of all units of the NWPS and a literature search were conducted to locate studies that provide campsite impact data, trail impact data, and information about visitor characteristics. Of the 628 wildernesses that comprised the NWPS in January 2000, 51 percent had baseline campsite data, 9 percent had trail condition data and 24 percent had data on visitor characteristics. Wildernesses managed by the Forest Service and National Park Service were much more likely to have data than wildernesses managed by the Bureau of Land Management and Fish and Wildlife Service. Both unpublished data collected by the management agencies and data published in reports are included. Extensive appendices provide detailed information about available data for every study that we located. These have been organized by wilderness so that it is easy to locate all the information available for each wilderness in the NWPS. Keywords: campsite condition, monitoring, National Wilderness Preservation System, trail condition, visitor characteristics The Authors _______________________________________ David N. -

New Mexico New Mexico

NEW MEXICO NEWand MEXICO the PIMERIA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves NEW MEXICO AND THE PIMERÍA ALTA NEWand MEXICO thePI MERÍA ALTA THE COLONIAL PERIOD IN THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEst edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2017 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-573-4 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-574-1 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Douglass, John G., 1968– editor. | Graves, William M., editor. Title: New Mexico and the Pimería Alta : the colonial period in the American Southwest / edited by John G. Douglass and William M. Graves. Description: Boulder : University Press of Colorado, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016044391| ISBN 9781607325734 (cloth) | ISBN 9781607325741 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Spaniards—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. | Spaniards—Southwest, New—History. | Indians of North America—First contact with Europeans—Pimería Alta (Mexico and Ariz.)—History. -

Ground-Water Geochemistry of the Albuquerque-Belen Basin, Central New Mexico

GROUND-WA TER GEOCHEMISTRY OF THE ALBVQVERQVE-BELEN BASIN, CENTRAL NEW MEXICO By Scott K. Anderholm U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 86-4094 Albuquerque, New Mexico 1988 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can write to: be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Water Resources Division Books and Open-File Reports Pinetree Office Park Federal Center, Building 810 4501 Indian School Rd. NE, Suite 200 Box 25425 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87110 Denver, Colorado 80225 CONTENTS Page Abstract ............................................................. 1 Introduction ......................................................... 2 Acknowledgments ................................................. 4 Purpose and scope ............................................... 4 Location ........................................................ 4 Climate ......................................................... 6 Previous investigations ......................................... 6 Geology .................................................... 6 Hydrology .................................................. 6 Well-numbering system ........................................... 9 Geology .............................................................. 10 Precambrian rocks ............................................... 10 Paleozoic rocks ................................................. 10 Mesozoic -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Trails in the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Area Recently Maintained & Cleared

l y R. 13 W. R. 12 W. R. 11 W. r l R. 10 W. t R. 9 W. R. 8 W. i r e t e 108°0'W m 107°45'W a v w o W a P S S le 11 Sawmill t Boundary Tank F t 6 40 10 i 1 6 Peak L 5 6 7M 10 11 9 1:63,360 0 0 8 9 12 8 8350 anyon Houghton Spring 4 7 40 7 5 7 T e C 1 in = 1 miles 11 12 4 71 7 7 0 Klin e C 10 0 C H 6 0 7 in Water anyon 8 9 6 a 4 0 Ranch P 4065A 7 Do 6 n 4 073Q (printed on 36" x 42" portrait layout) Houghton ag Z y 4 Well 12 Corduroy Corral y Doagy o 66 11 n 5 aska 10 Spr. Spr. Tank K Al 0 0.25 0.5 1 1.5 2 9 Corduroy Tank 1 1 14 13 7 2 15 5 0 4 Miles 5 Doagie Spr. 5 16 9 Beechnut Tank 4 0 17 6 13 18 n 8 14 yo 1 15 an Q C Deadman Tank 16 D Coordinate System: NAD 1983 UTM Zone 12NTransverse Mercator 3 3 3 17 0 r C 2 Sawmill 1 0 Rock 7 18 a Alamosa 13 w 6 1 Spr. Core 14 Attention: Reilly 6 Dirt Tank 8 15 0 Peak 14 Dev. Tank 3 Clay 4 15 59 16 Gila National Forest uses the most current n 0 16 S o 17 13 Santana 8163 1 17 3 y Doubleheader #2 Tank 18 Fence Tank Cr. -

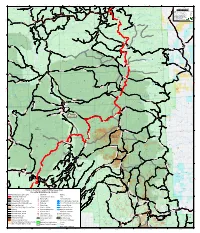

Rimrock Rose Ranch Acquisition and Taos Resource Management Plan Amendment Addressing Livestock Grazing on Two Allotments in Sabinoso Wilderness

Rimrock Rose Ranch Acquisition and Taos Resource Management Plan Amendment Addressing Livestock Grazing on Two Allotments in Sabinoso Wilderness Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-NM-F020-2016-0011-EA Taos Field Office 226 Cruz Alta Road Taos, New Mexico 87571 Rimrock Rose Ranch Acquisition and Taos Resource Management Plan Amendment Addressing Livestock Grazing on Two Allotments in Sabinoso Wilderness Environmental Assessment DOI-BLM-NM-F020-2016-0011-EA Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Background ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Purpose and Need for Action ........................................................................................... 4 1.3 Land Use Plan Conformance............................................................................................ 4 1.4 Decisions to be Made ....................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Applicable Authorities ..................................................................................................... 5 1.6 Identification of Issues ..................................................................................................... 6 1.7 Issues Considered -

Stratigraphic Nomenclature of ' Volcanic Rocks in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico

-» Stratigraphic Nomenclature of ' Volcanic Rocks in the Jemez Mountains, New Mexico By R. A. BAILEY, R. L. SMITH, and C. S. ROSS CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY » GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1274-P New Stratigraphic names and revisions in nomenclature of upper Tertiary and , Quaternary volcanic rocks in the Jemez Mountains UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1969 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 15 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract.._..._________-...______.._-.._._____.. PI Introduction. -_-________.._.____-_------___-_______------_-_---_-_ 1 General relations._____-___________--_--___-__--_-___-----___---__. 2 Keres Group..__________________--------_-___-_------------_------ 2 Canovas Canyon Rhyolite..__-__-_---_________---___-____-_--__ 5 Paliza Canyon Formation.___-_________-__-_-__-__-_-_______--- 6 Bearhead Rhyolite-___________________________________________ 8 Cochiti Formation.._______________________________________________ 8 Polvadera Group..______________-__-_------________--_-______---__ 10 Lobato Basalt______________________________________________ 10 Tschicoma Formation_______-__-_-____---_-__-______-______-- 11 El Rechuelos Rhyolite--_____---------_--------------_-_------- 11 Puye Formation_________________------___________-_--______-.__- 12 Tewa Group__._...._.______........___._.___.____......___...__ 12 Bandelier Tuff.______________.______________... 13 Tsankawi Pumice Bed._____________________________________ 14 Valles Rhyolite______.__-___---_____________.________..__ 15 Deer Canyon Member.______-_____-__.____--_--___-__-____ 15 Redondo Creek Member.__________________________________ 15 Valle Grande Member____-__-_--___-___--_-____-___-._-.__ 16 Battleship Rock Member...______________________________ 17 El Cajete Member____..._____________________ 17 Banco Bonito Member.___-_--_---_-_----_---_----._____--- 18 References . -

Geothermal Hydrology of Valles Caldera and the Southwestern Jemez Mountains, New Mexico

GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER GEOTHERMAL HYDROLOGY OF VALLES CALDERA AND THE SOUTHWESTERN JEMEZ MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO By Frank W. Trainer, Robert J. Rogers, and Michael L. Sorey U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 00-4067 Prepared in cooperation with the OFFICE OF THE STATE ENGINEER Albuquerque, New Mexico 2000 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Charles G. Groat, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Information Services Water Resources Division Box 25286 5338 Montgomery NE, Suite 400 Denver, CO 80225-0286 Albuquerque, NM 87109-1311 Information regarding research and data-collection programs of the U.S. Geological Survey is available on the Internet via the World Wide Web. You may connect to the Home Page for the New Mexico District Office using the URL: http://nm.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Page Abstract............................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................ 2 Purpose and scope........................................................................................................................ -

Issues in the 111Th Congress

Federal Lands Managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service (FS): Issues in the 111th Congress (name redacted), Coordinator Specialist in Natural Resources Policy (name redacted), Coordinator Specialist in Natural Resources Policy (name redacted) Legislative Attorney (name redacted) Analyst in Energy Policy October 22, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R40237 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Federal Lands Managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service Summary Congress, the Administration, and the courts are considering many issues related to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) public lands and the Forest Service (FS) national forests. Key issues include the following. Energy Resources. The Energy Policy Act of 2005 (P.L. 109-58) led to new regulations on federal land leasing for oil and gas, oil shale, geothermal, and renewable energy. The Obama Administration is reviewing some rules and has withdrawn certain oil and gas leases in Utah. Hardrock Mining. The General Mining Law of 1872 allows prospecting for minerals in open public domain lands. Several bills to reform aspects of the Law have been introduced to require royalties on production and establish a fund to clean up abandoned mines, among other changes. Wildfire Protection. Various initiatives seek to protect communities from wildfires by expanding fuel reduction, and one related program was established in P.L. 111-11. Cost concerns led to new fire suppression accounts in the FLAME Act (Title V of P.L. 111-88). Wild Horses and Burros. To reduce program costs and the number of wild horses and burros on the range, the Secretary of the Interior has proposed wild horse preserves and increased fertility controls. -

New Mexico Geological Society Spring Meeting Abstracts

the surface water system. Snow melt in the high VOLCANIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE WEST- mountains recharges shallow perched aquifers ERN SIERRA BLANCA VOLCANIC FIELD, Abstracts that discharge at springs that feed streams and SOUTH-CENTRAL NEW MEXICO, S. A. Kel- ponds where evaporation occurs. Water in ponds ley, [email protected], and D. J. Koning, and streams may then recharge another shallow New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral perched aquifer, which again may discharge at a Resources, New Mexico Institute of Mining and spring at a lower elevation. This cycle may occur Technology, Socorro, New Mexico 87801; K. A. New Mexico Geological Society several times until the water is deep enough to be Kempter, 2623 Via Caballero del Norte, Santa Fe, spring meeting isolated from the surface water system. A deeper New Mexico 87505; K. E. Zeigler, Zeigler Geo- regional aquifer may exist in this area. East of logic Consulting, Albuquerque, New Mexico The New Mexico Geological Society annual Mayhill along the Pecos Slope, regional ground 87123; L. Peters, New Mexico Bureau of Geology spring meeting was held on April 16, 2010, at the water flow is dominantly to the east toward the and Mineral Resources, New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology, Socorro, New Mex- Macey Center, New Mexico Tech, Socorro. Fol- Roswell Artesian Basin. Some ground water also ico 87801; and F. Goff, Department of Earth and lowing are the abstracts from all sessions given flows to the southeast toward the Salt Basin and to the west into the Tularosa Basin. Planetary Sciences, University of New Mexico, at that meeting.