Repositorio CICY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master CAMA LMP Template 20030122

Wet Woods Preserve Land Management Plan Wet Woods Preserve Land Management Plan Managed by: Conservation Collier Program Collier County May 2008 –May 2018 (10 yr plan) Updated: December 2015 Prepared by: Collier County Parks and Recreation Division Conservation Collier Staff Conservation Collier Program 1 Wet Woods Preserve Land Management Plan Wet Woods Preserve Land Management Plan Executive Summary Lead Agency: Collier County Board of County Commissioners, Conservation Collier Program Property included in this Plan: Wet Woods Preserve (Folio #: 00154880008) Acreage Breakdown: General Vegetative Communities Acreage Wetlands (58%) 15.53 Uplands (42%) 11.24 TOTAL 26.77 Management Responsibilities: Agency: Collier County - Conservation Collier Program Designated Land Use: Conservation and natural resource based recreation Unique Features: saltwater and freshwater marshes, mangrove forests, pine flatwoods, active bald eagle nest, seven listed plant and two listed animal species detected to date Management Goals: Goal 1: Eliminate or significantly reduce human impacts to indigenous flora and fauna Goal 2: Develop a baseline monitoring report Goal 3: Remove or control populations of invasive, exotic or problematic flora and fauna to restore and maintain natural habitats Goal 4: Continue to implement a mechanical treatment schedule to decrease woody fuels Goal 5: Restore native vegetation Goal 6: Facilitate uses of the site for educational purposes Goal 7: Provide a plan for security and disaster preparedness Public Involvement: Public meeting(s) were held in early spring of 2008 with invitations being sent to residents and businesses from surrounding lands. Conservation Collier Program 2 Wet Woods Preserve Land Management Plan Table of Contents Land Management Plan Executive Summary ................................................................ 2 List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0263516 A1 CYR (43) Pub

US 20090263516A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0263516 A1 CYR (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 22, 2009 (54) PLANT EXTRACT COMPOSITION AND Publication Classification THEIR USE TO MODULATE CELLULAR (51) Int. Cl. ACTIVITY A636/8962 (2006.01) A636/00 (2006.01) (75) Inventor: Benoit CYR, St. Augustin de A6IP35/00 (2006.01) Desmaures (CA) CI2N 5/06 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6IR 36/3 (2006.01) SHEPPARD, MULLIN, RICHTER & HAMPTON A 6LX 36/899 (2006.01) LLP (52) U.S. Cl. ......... 424/754; 424/725; 435/375; 424/774; 990 Marsh Road 424/779; 424/755; 424/750; 424/777 Menlo Park, CA 94025 (US) (57) ABSTRACT (73) Assignee: Biopharmacopae Design Extracts from plant material, or semi-purified/purified mol International Inc., Saint-Foy (CA) ecules or compounds prepared from the extracts that demon strate the ability to modulate one or more cellular activities (21) Appl. No.: 12/263,114 are provided. The extracts are capable of slowing down, inhibiting or preventing cell migration, for example, the (22) Filed: Oct. 31, 2008 migration of endothelial cells or neoplastic cells and thus, the use of the extracts to slow down, inhibit or prevent abnormal Related U.S. Application Data cell migration in an animal is also provided. Methods of selecting and preparing the plant extracts and methods of (63) Continuation of application No. 10/526,387, filed on screening the extracts to determine their ability to modulate Oct. 6, 2005, now abandoned, filed as application No. one or more cellular activity are described. The purification or PCT/CA03/01284 on Sep. -

Comparative Study of Preliminary Antimicrobial Activity of Three Different Plant Extracts

Mohammad Nazmul Alam, et al. Int J Pharm 2015; 5(4): 1087-1090 ISSN 2249-1848 International Journal of Pharmacy Journal Homepage: http://www.pharmascholars.com Research Article CODEN: IJPNL6 COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRELIMINARY ANTIMICROBIAL ACTIVITY OF THREE DIFFERENT PLANT EXTRACTS Mohammad Nazmul Alam1*, Md. Hasibur Rahman1, Md. Jainul Abeden1, Md. Faruk1, Md. Shahrear Biozid1, Sudipta Chowdhury1, Md. Rafikul Islam1, Mohammed Abu Sayeed1 1Department of Pharmacy, Faculty of Science and Engineering, International Islamic University Chittagong, 154/A, College Road, Chittagong-4203, Bangladesh. *Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Disk diffusion method was performed to evaluate the ex-vivo comparative study of preliminary antimicrobial activity of methanolic extract of Thunbergia grandiflora, Breynia retusa and Nymphaea capensis leaves. Among the three plants, T. grandiflora and N. capensis showed more antibacterial activity than B. retusa. T. grandiflora showed its highest activity against a gram positive bacterium Bacillus cereus with the inhibition ring of 17 mm in diameter at 1000 µg/disc. In case of B. retusa, highest activity was found against the gram negative bacterium Salmonella typhi which is 16 mm at 1000 µg/disc. N. capensis exhibited its highest antibacterial activity against the gram negative bacterium Escherichia coli which is 19 mm at 1000 µg/disc. KEYWORDS: T. grandiflora, B. retusa, N. capensis, antimicrobial activity, comparative study, disc diffusion method, Kanamycin. INTRODUCTION tropical countries of Africa [4]. It is also found throughout the Bangladesh, especially in forests of In this world microorganisms are the main reason for Gajipur, Chittagong, Chittagong Hill Tracts, Cox's mortality and morbidity [1]. Antimicrobial agents are Bazar, Tangail [5]. -

February 1993 Newsletter

■ —« \ V*. Odotitoglossum Alliance and popular pot plants. Earlier in this century a INTEBNATIONAL number of exciting hybrids were created with miltonopsis and other members of the ODONTOGLOSSUM odontoglossum alliance. Vuylstekeara Cambria, FORUIVI 1 4th registered in 1932, is a perfect example of this type of hybridizing. This lecture will explore the WORLD ORCHID beautiful and new miltonopsis hybrids being CONGRESS created today including new odontonias, vuylstekearas, miltonidiums, miltoniodas, colmanaras and burragearas. GLASGOW.SCOTLAND Dr. Howard Liebman has been raising orchids for over 30 years and has been growing and APRIL 30, 1993 hybridizing odontoglossums and miltonopsis hybrids for over 20 years. He has registered 150 The International Odontoglossum Alliance forum crosses in the odontoglossum and miltonopsis theme is "Enlarging the Growing of the alliance and over 30 of his crosses have received Odontoglossum Alliance". The program will awards from various orchid societies including offer four lectures, followed by a luncheon. the AOS and RHS. He has also presented papers There is an evening dinner planned with informal at two previous World Orchid Congresses. remarks by Allan Moon, curator of the Eric Professionally, Dr. Howard Liebman is a Young Orchid Foundation. physician-scientist and a professor of medicine Lectures and pathology at the University of Southern 0930 - 1230 California School of Medicine. He is the author 0930 Program Session Chairman: Mr. Michael of over 50 scientific papers on blood diseases and Tibbs aids. Michael Tibbs recently became owner of The 2. Survey of Odontoglossum Alliance Interest Exotic Plant Company Ltd. West Sussex. He has and Growing in Australia, by Philip Altmann experienced working in nurseries in Ardingly, With increasing interest among orchid growers in West Sussex, England, Japan and the Far East. -

FINAL REPORT PSRA Vegetation Monitoring 2005-2006 PC P502173

Rare Plants and Their Locations at Picayune Strand Restoration Area: Task 4a FINAL REPORT PSRA Vegetation Monitoring 2005-2006 PC P502173 Steven W. Woodmansee and Michael J. Barry [email protected] December 20, 2006 Submitted by The Institute for Regional Conservation 22601 S.W. 152 Avenue, Miami, Florida 33170 George D. Gann, Executive Director Submitted to Mike Duever, Ph.D. Senior Environmental Scientist South Florida Water Management District Fort Myers Service Center 2301 McGregor Blvd. Fort Myers, Florida 33901 Table of Contents Introduction 03 Methods 03 Results and Discussion 05 Acknowledgements 38 Citations 39 Tables: Table 1: Rare plants recorded in the vicinity of the Vegetation Monitoring Transects 05 Table 2: The Vascular Plants of Picayune Strand State Forest 24 Figures: Figure 1: Picayune Strand Restoration Area 04 Figure 2: PSRA Rare Plants: Florida Panther NWR East 13 Figure 3: PSRA Rare Plants: Florida Panther NWR West 14 Figure 4: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Northeast 15 Figure 5: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Northwest 16 Figure 6: PSRA Rare Plants: FSPSP West 17 Figure 7: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Southeast 18 Figure 8: PSRA Rare Plants: PSSF Southwest 19 Figure 9: PSRA Rare Plants: FSPSP East 20 Figure 10: PSRA Rare Plants: TTINWR 21 Cover Photo: Bulbous adder’s tongue (Ophioglossum crotalophoroides), a species newly recorded for Collier County, and ranked as Critically Imperiled in South Florida by The Institute for Regional Conservation taken by the primary author. 2 Introduction The South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) plans on restoring the hydrology at Picayune Strand Restoration Area (PSRA) see Figure 1. -

Pollen Ontogeny in Victoria (Nymphaeales)

Int. J. Plant Sci. 174(9):1259–1276. 2013. ᭧ 2013 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/2013/17409-0006$15.00 DOI: 10.1086/673246 POLLEN ONTOGENY IN VICTORIA (NYMPHAEALES) Mackenzie L. Taylor,1,* Patrick J. Hudson,2,† Jolene M. Rigg,† Julie N. Strandquist,† Julie Schwartz Green,3,† Tara C. Thiemann,4,† and Jeffrey M. Osborn‡ *Department of Biology, Creighton University, Omaha, Nebraska 68178, USA; †Department of Biology, Truman State University, Kirksville, Missouri 63501, USA; and ‡School of Science, College of New Jersey, Ewing, New Jersey 08628, USA Editor: William E. Friedman Premise of research. Water lilies (Nymphaeales) make up one of the oldest independent lineages of an- giosperms. The giant water lily, Victoria, exhibits pollination and floral traits that are derived within Nym- phaeales. Specialization in pollination and floral biology is often reflected in pollen traits, and in Victoria,this is evidenced by the production of permanent tetrads. Compound pollen has evolved many times across the angiosperm phylogeny, but compound pollen development has been investigated in only a few taxa, and the degree of developmental variation in microspore cohesion is unknown. This article comprehensively charac- terizes the pollen ontogenetic sequence in Victoria for the first time. Methodology. Floral buds of Victoria amazonica, Victoria cruziana, and Longwood hybrid were field collected. Anthers at the sporogenous, microspore mother cell, tetrad, “free” microspore, and mature pollen grain stages were studied using combined LM/SEM/TEM. Pivotal results. Microspore cohesion in Victoria differs from that exhibited by the few compound pollen- producing taxa that have been studied. In Victoria, the calymmate tetrads fuse via crosswall cohesion, but cytoplasmic connections are transient and do not serve as a template for wall bridge formation. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

Terminalia Buceras: Black Olive1 Edward F

ENH261 Terminalia buceras: Black Olive1 Edward F. Gilman, Dennis G. Watson, Ryan W. Klein, Andrew K. Koeser, Deborah R. Hilbert, and Drew C. McLean2 Introduction Though commonly called `Black olive tree’, this native of the upper Florida Keys (some consider it native, others do not) is not the edible olive we know and love, but does produce a small, black seed-capsule. Black olive is a 40 to 50-foot-tall evergreen tree with a smooth trunk holding up strong, wind-resistant branches, forming a pyramidal shape when young but developing a very dense, full, oval to rounded crown with age. Sometimes the top of the crown will flatten with age, and the tree grows horizontally. The lush, dark green, leathery leaves are two to four inches long and clustered at branch tips, sometimes mixed with the 1/4 to 1 ½-inch-long spines found along the branches. General Information Scientific name: Terminalia buceras Pronunciation: ter-mih-NAIL-ee-uh bew-SER-azz Common name(s): black olive, oxhorn bucida Family: Combretaceae USDA hardiness zones: 10B through 11 (Figure 2) Origin: native to the West Indies Figure 1. Full Form - Terminalia buceras: black olive UF/IFAS Invasive Assessment Status: Caution, may be Credits: UF/IFAS recommended but manage to prevent escape (South); Not considered a problem species at this time, may be recom- Uses: hedge; reclamation; street without sidewalk; shade; mended (North and Central) specimen; tree lawn 4–6 feet wide; tree lawn > 6 ft wide; urban tolerant; highway median; indoors 1. This document is ENH261, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. -

Dicotyledons

Dicotyledons COMBRETACEAE R. Br., nom. cons. 1810. COMBRETUM FAMILY Shrubs, trees, or woody vines. Leaves alternate or opposite, simple, pinnate-veined, petiolate, stipulate or estipulate. Flowers in terminal or axillary spikes, racemes, panicles, or heads, acti- nomorphic, bisexual or unisexual (staminate) (plants dioecious or polygamodioecious), brac- teate, bracteolate or ebracteolate; hypanthium prolonged beyond the ovary, the lower part adnate to the ovary, the upper part free; sepals 4 or 5, connate; petals 5 and free or absent; nec- taries present; stamens 5–10, the filaments free, the anthers 2-locular, versatile, longitudinally dehiscent; ovary 2- to 5-carpellate, 1-loculate, the style 1. Fruit a drupe. A family of 14 genera and about 500 species; nearly cosmopolitan. Terminaliaceae J. St.-Hil. (1805).proof Selected references: Graham (1964b); Stace (2010). 1. Leaves opposite, decussate. 2. Tree or erect shrub; petiole with nectar glands; flowers inconspicuous, the petals ca. 1 mm long, greenish white ...........................................................................................................................Laguncularia 2. Vine or scandent shrub; petiole without nectar glands; flowers showy, the petals 1–2 cm long, white to pink or red ..............................................................................................................................Combretum 1. Leaves alternate, spiral. 3. Flowers in dense spherical or oblong heads; fruits in a dry, conelike head ....................Conocarpus 3. Flowers -

Threatened and Endangered Species List

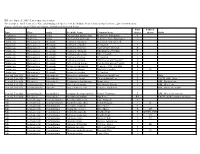

Effective April 15, 2009 - List is subject to revision For a complete list of Tennessee's Rare and Endangered Species, visit the Natural Areas website at http://tennessee.gov/environment/na/ Aquatic and Semi-aquatic Plants and Aquatic Animals with Protected Status State Federal Type Class Order Scientific Name Common Name Status Status Habit Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus gulolineatus Berry Cave Salamander T Amphibian Amphibia Anura Gyrinophilus palleucus Tennessee Cave Salamander T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus bouchardi Big South Fork Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus cymatilis A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus deweesae Valley Flame Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus extraneus Chickamauga Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus obeyensis Obey Crayfish T Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus pristinus A Crayfish E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Cambarus williami "Brawley's Fork Crayfish" E Crustacean Malacostraca Decapoda Fallicambarus hortoni Hatchie Burrowing Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes incomptus Tennessee Cave Crayfish E Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes shoupi Nashville Crayfish E LE Crustacean Malocostraca Decapoda Orconectes wrighti A Crayfish E Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris carthusiana Spinulose Shield Fern T Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Dryopteris cristata Crested Shield-Fern T FACW, OBL, Bogs Fern and Fern Ally Filicopsida Polypodiales Trichomanes boschianum -

E29695d2fc942b3642b5dc68ca

ISSN 1409-3871 VOL. 9, No. 1—2 AUGUST 2009 Orchids and orchidology in Central America: 500 years of history CARLOS OSSENBACH INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON ORCHIDOLOGY LANKESTERIANA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON ORCHIDOLOGY Copyright © 2009 Lankester Botanical Garden, University of Costa Rica Effective publication date: August 30, 2009 Layout: Jardín Botánico Lankester. Cover: Chichiltic tepetlauxochitl (Laelia speciosa), from Francisco Hernández, Rerum Medicarum Novae Hispaniae Thesaurus, Rome, Jacobus Mascardus, 1628. Printer: Litografía Ediciones Sanabria S.A. Printed copies: 500 Printed in Costa Rica / Impreso en Costa Rica R Lankesteriana / International Journal on Orchidology No. 1 (2001)-- . -- San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Universidad de Costa Rica, 2001-- v. ISSN-1409-3871 1. Botánica - Publicaciones periódicas, 2. Publicaciones periódicas costarricenses LANKESTERIANA i TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Geographical and historical scope of this study 1 Political history of Central America 3 Central America: biodiversity and phytogeography 7 Orchids in the prehispanic period 10 The area of influence of the Chibcha culture 10 The northern region of Central America before the Spanish conquest 11 Orchids in the cultures of Mayas and Aztecs 15 The history of Vanilla 16 From the Codex Badianus to Carl von Linné 26 The Codex Badianus 26 The expedition of Francisco Hernández to New Spain (1570-1577) 26 A new dark age 28 The “English American” — the journey through Mexico and Central America of Thomas Gage (1625-1637) 31 The renaissance of science -

Combretaceae: Phylogeny, Biogeography and DNA

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012) Title of the thesis or dissertation. PhD. (Chemistry)/ M.Sc. (Physics)/ M.A. (Philosophy)/M.Com. (Finance) etc. [Unpublished]: University of Johannesburg. Retrieved from: https://ujdigispace.uj.ac.za (Accessed: Date). Combretaceae: Phylogeny, Biogeography and DNA Barcoding by JEPHRIS GERE THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in BOTANY in the Faculty of Science at the University of Johannesburg December 2013 Supervisor: Prof Michelle van der Bank Co-supervisor: Dr Olivier Maurin Declaration I declare that this thesis has been composed by me and the work contained within, unless otherwise stated, is my own. _____________________ J. Gere (December 2013) Table of contents Table of contents i Abstract v Foreword vii Index to figures ix Index to tables xv Acknowledgements xviii List of abbreviations xxi Chapter 1: General introduction and objectives 1.1 General introduction 1 1.2 Vegetative morphology 2 1.2.1 Leaf morphology and anatomy 2 1.2.2. Inflorescence 3 1.2.3 Fruit morphology 4 1.3 DNA barcoding 5 1.4 Cytology 6 1.5 Fossil record 7 1.6 Distribution and habitat 7 1.7 Economic Importance 8 1.8 Taxonomic history 9 1.9 Aims and objectives of the study 11 i Table of contents Chapter 2: Molecular phylogeny of Combretaceae with implications for infrageneric classification within subtribe Terminaliinae.