Pdf [ (Providing Background on the Bomb Threat and the FBI’S Decision to Impersonate a Member of the Me- Dia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Censorship and the First Amendment Robert A

Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy Volume 25 Article 2 Issue 1 Symposium on Censorship & the Media 1-1-2012 Self-Censorship and the First Amendment Robert A. Sedler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp Recommended Citation Robert A. Sedler, Self-Censorship and the First Amendment, 25 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol'y 13 (2012). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndjlepp/vol25/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES SELF-CENSORSHIP AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT ROBERT A. SEDLER* I. INTRODUCTION Self-censorship refers to the decision by an individual or group to refrain from speaking and to the decision by a media organization to refrain from publishing information. Whenever an individual or group or the media engages in self-censorship, the values of the First Amendment are compromised, because the public is denied information or ideas.' It should not be sur- prising, therefore, that the principles, doctrines, and precedents of what I refer to as "the law of the First Amendment"' are designed to prevent self-censorship premised on fear of govern- mental sanctions against expression. This fear-induced self-cen- sorship will here be called "self-censorship bad." At the same time, the First Amendment also values and pro- tects a right to silence. -

Bloggers and Netizens Behind Bars: Restrictions on Internet Freedom In

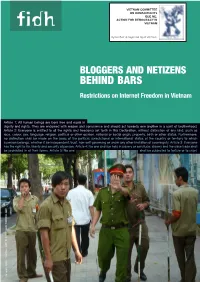

VIETNAM COMMITTEE ON HUMAN RIGHTS QUÊ ME: ACTION FOR DEMOCRACY IN VIETNAM Ủy ban Bảo vệ Quyền làm Người Việt Nam BLOGGERS AND NETIZENS BEHIND BARS Restrictions on Internet Freedom in Vietnam Article 1: All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood. Article 2: Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty. Article 3: Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person. Article 4: No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms. Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, January 2013 / n°603a - AFP PHOTO IAN TIMBERLAKE Cover Photo : A policeman, flanked by local militia members, tries to stop a foreign journalist from taking photos outside the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Court during the trial of a blogger in August 2011 (AFP, Photo Ian Timberlake). 2 / Titre du rapport – FIDH Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------5 -

The Stored Communications Act, Gag Orders, and the First Amendment

10 BURKE (DO NOT DELETE) 12/13/2017 1:29 PM WHEN SILENCE IS NOT GOLDEN: THE STORED COMMUNICATIONS ACT, GAG ORDERS, AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT Alexandra Burke* I. INTRODUCTION Cloud computing has completely changed the landscape of information storage. Sensitive information that was once stored in file cabinets and eventually on computers is now stored remotely using web-based cloud computing services.1 The cloud’s prevalence in today’s world is undeniable, as recent studies show that nearly forty percent of all Americans2 and an estimated ninety percent of all businesses use the cloud in some capacity.3 Despite this fact, Congress has done little in recent years to protect users and providers of cloud computing services.4 What Congress has done dates back to its enactment of the Stored Communications Act (SCA) in 1986.5 Passed decades before the existence *J.D. Candidate, 2018, Baylor University School of Law; B.B.A. Accounting, 2015, Texas A&M University. I would like to extend my gratitude to each of the mentors, professors, and legal professionals who have influenced my understanding of and appreciation for the law. Specifically, I would like to thank Professor Brian Serr for his guidance in writing this article. Finally, I would like to acknowledge my family and friends, who have always shown me unwavering support. 1 See Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473, 2491 (2014) (defining cloud computing as “the capacity of Internet-connected devices to display data stored on remote servers rather than on the device itself”); see also Paul Ohm, The Fourth Amendment in a World Without Privacy, 81 MISS. -

Case 4:15-Cv-00358-O Document 41 Filed 06/17/21 Page 1 of 28 Pageid 502

Case 4:15-cv-00358-O Document 41 Filed 06/17/21 Page 1 of 28 PageID 502 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION, CIVIL ACTION NO: 4:15-cv-358-O Plaintiff, v. CHRISTOPHER A. NOVINGER, et al., Defendants. June 17, 2021 MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO REOPEN AND FOR RELIEF FROM JUDGMENT PURSUANT TO F. R. Civ. P. 60(b) and subsect. (4) and (5) Margaret A. Little N.D. Tex. Bar No. 303494CT Kara M. Rollins, pro hac vice forthcoming New Civil Liberties Alliance 1225 19th St. NW, Suite 450 Washington, DC 20036 Telephone: 202-869-5210 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Movants Christopher A. Novinger and ICAN Investment Group, LLC Case 4:15-cv-00358-O Document 41 Filed 06/17/21 Page 2 of 28 PageID 503 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................. i PRELIMINARY STATEMENT .................................................................................................... 1 FACTS AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT .................................................................................................................................. 3 I. STANDARDS RELATING TO RULE 60(b)(4) MOTIONS ........................................................... 3 II. THE GAG ORDER VIOLATES THE FIRST AMENDMENT ......................................................... -

Hunting for Hackers, N.S.A. Secretly Expands Internet Spying at U.S. Border - Nytimes.Com

6/4/2015 Hunting for Hackers, N.S.A. Secretly Expands Internet Spying at U.S. Border - NYTimes.com http://nyti.ms/1dP5ida POLITICS Hunting for Hackers, N.S.A. Secretly Expands Internet Spying at U.S. Border By CHARLIE SAVAGE, JULIA ANGWIN, JEFF LARSON and HENRIK MOLTKE JUNE 4, 2015 WASHINGTON — Without public notice or debate, the Obama administration has expanded the National Security Agency’s warrantless surveillance of Americans’ international Internet traffic to search for evidence of malicious computer hacking, according to classified N.S.A. documents. In mid-2012, Justice Department lawyers wrote two secret memos permitting the spy agency to begin hunting on Internet cables, without a warrant and on American soil, for data linked to computer intrusions originating abroad — including traffic that flows to suspicious Internet addresses or contains malware, the documents show. The Justice Department allowed the agency to monitor only addresses and “cybersignatures” — patterns associated with computer intrusions — that it could tie to foreign governments. But the documents also note that the N.S.A. sought permission to target hackers even when it could not establish any links to foreign powers. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/05/us/hunting-for-hackers-nsa-secretly-expands-internet-spying-at-us-border.html?emc=eta1&_r=0 1/6 6/4/2015 Hunting for Hackers, N.S.A. Secretly Expands Internet Spying at U.S. Border - NYTimes.com The disclosures, based on documents provided by Edward J. Snowden, the former N.S.A. contractor, and shared with The New York Times and ProPublica, come at a time of unprecedented cyberattacks on American financial institutions, businesses and government agencies, but also of greater scrutiny of secret legal justifications for broader government surveillance. -

Electronic Communications Surveillance

Electronic Communications Surveillance LAUREN REGAN “I think you’re misunderstanding the perceived problem here, Mr. President. No one is saying you broke any laws. We’re just saying it’s a little bit weird that you didn’t have to.”—John Oliver on The Daily Show1 The government is collecting information on millions of citizens. Phone, Internet, and email habits, credit card and bank records—vir- tually all information that is communicated electronically is subject to the watchful eye of the state. The government is even building a nifty, 1.5 million square foot facility in Utah to house all of this data.2 With the recent exposure of the NSA’s PRISM program by whistleblower Edward Snowden, many people—especially activists—are wondering: How much privacy do we actually have? Well, as far as electronic pri- vacy, the short answer is: None. None at all. There are a few ways to protect yourself, but ultimately, nothing in electronic communications is absolutely protected. In the United States, surveillance of electronic communications is governed primarily by the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA), which is an extension of the 1968 Federal Wiretap act (also called “Title III”) and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Other legislation, such as the USA PATRIOT Act and the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA), sup- plement both the ECPA and FISA. The ECPA is divided into three broad areas: wiretaps and “electronic eavesdropping,” stored messages, and pen registers and trap-and-trace devices. Each degree of surveillance requires a particular burden that the government must meet in order to engage in the surveillance. -

Summary of U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Law, Practice, Remedies, and Oversight

___________________________ SUMMARY OF U.S. FOREIGN INTELLIGENCE SURVEILLANCE LAW, PRACTICE, REMEDIES, AND OVERSIGHT ASHLEY GORSKI AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION AUGUST 30, 2018 _________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS QUALIFICATIONS AS AN EXPERT ............................................................................................. iii INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 I. U.S. Surveillance Law and Practice ................................................................................... 2 A. Legal Framework ......................................................................................................... 3 1. Presidential Power to Conduct Foreign Intelligence Surveillance ....................... 3 2. The Expansion of U.S. Government Surveillance .................................................. 4 B. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 ..................................................... 5 1. Traditional FISA: Individual Orders ..................................................................... 6 2. Bulk Searches Under Traditional FISA ................................................................. 7 C. Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act ........................................... 8 D. How The U.S. Government Uses Section 702 in Practice ......................................... 12 1. Data Collection: PRISM and Upstream Surveillance ........................................ -

Limitless Surveillance at the Fda: Pro- Tecting the Rights of Federal Whistle- Blowers

LIMITLESS SURVEILLANCE AT THE FDA: PRO- TECTING THE RIGHTS OF FEDERAL WHISTLE- BLOWERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 26, 2014 Serial No. 113–88 Printed for the use of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–176 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 11:40 Mar 31, 2014 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\DOCS\87176.TXT APRIL COMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND GOVERNMENT REFORM DARRELL E. ISSA, California, Chairman JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland, Ranking MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio Minority Member JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM JORDAN, Ohio Columbia JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts TIM WALBERG, Michigan WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts JUSTIN AMASH, Michigan JIM COOPER, Tennessee PAUL A. GOSAR, Arizona GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania JACKIE SPEIER, California SCOTT DESJARLAIS, Tennessee MATTHEW A. CARTWRIGHT, Pennsylvania TREY GOWDY, South Carolina TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois DOC HASTINGS, Washington DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois CYNTHIA M. LUMMIS, Wyoming PETER WELCH, Vermont ROB WOODALL, Georgia TONY CARDENAS, California THOMAS MASSIE, Kentucky STEVEN A. -

FBI's Carnivore: How Federal Agents May Be Viewing Your Personal E-Mail and Why There Is Nothing You Can Do About It

The FBI's Carnivore: How Federal Agents May Be Viewing Your Personal E-Mail and Why There Is Nothing You Can Do About It PETER J. GEORGITON* Much controversy has arisen over the FBI's proposal to use an e-mail and Internet surveillanceprogram, named "Carnivore," to assist its law enforcement efforts on the Information Superhighway. In this note, the authorexamines how Carnivoreoperates and its implicationsfor individuals 'privacy rights under the Fourth Amendment and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA). The author concludes that the current state of constitutional and statutory law governing electronicsurveillance indicates that the FBI can utilize Carnivore to conduct a wide range of intrusive searches with little or no legal justification. Carnivore'sability to retrieve more than mere e-mail messages of suspects, the FBI's checkered past on privacy issues, and the lack ofjudicial oversight make the potentialfor abuse of Carnivoregreat. As a result, Congress must take a hard look at both the ECPA and Carnivore to prevent law enforcement agenciesfrom using Carnivore to peer into our personal e-mails and Internet usage. Whether he wrote DOWN WITH BIG BROTHER, or whether he refrainedfrom writing it, made no difference.... The Thought Police would get him just the same. He had committed-would still have committed, even ifhe had never set pen to paper-the essential crime that contained all others in itself Thoughtcrime, they called it. Thoughtcrime was not a thing that could be concealedforever. You might dodge successfully for a while, even for years, but sooner or laterthey were bound to get you. -

Independent Technical Review of the Carnivore System Final Report

Contract No. 00-C-0328 IITRI CR-030-216 Independent Technical Review of the Carnivore System Final Report 8 December 2000 Contract No. 00-C-0328 IITRI CR-030-216 Independent Review of the Carnivore System Final Report Prepared by: Stephen P. Smith J. Allen Crider Henry H. Perritt, Jr. Mengfen Shyong Harold Krent Larry L. Reynolds Stephen Mencik 8 December 2000 IIT Research Institute Suite 400 8100 Corporate Drive Lanham, Maryland 20785-2231 301-731-8894 FAX 301-731-0253 IITRI CR-030-216 CONTENTS Executive Summary.................................................................................................................. vii ES.1 Introduction................................................................................................................... vii ES.2 Scope............................................................................................................................. vii ES.3 Approach....................................................................................................................... viii ES.4 Observations ................................................................................................................. viii ES.5 Conclusions................................................................................................................... xii ES.6 Recommendations......................................................................................................... xiv Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose......................................................................................................................... -

Nor'easter News Volume 2 Issue 5

Established 2007 N ...........R'EASTER NEWS Make a Dif Setting the Re ference, Be a cord Straight Mentor on Housing BY ANDREW FREDETTE BY MICHAEL CAMPINELL Nor'easter Staff Nor'easter Staff Have you ever wondered Right after the hous what it would be like to have a ing selection for the 2009 - 2010 mentor when you where growing school year happened, rumors up? Wonder what the experience starting spreading like wildfire. might do for you and the experi This article is to help set those ru ence you might gain? Growing mors straight. Information in this up is a part of life that not ev article was received from Jennifer eryone wants to do. But there are Deburro-Jones, the Director oJ ways to revert to your child hood Residential Life at UNE. She and and feel like a kid again. UNE is I have spoke on several occasions running a mentor program with about the many different aspects the College Community Men of housing at UNE and she has toring Program. also sent me answers to specific The program consists of 55 questions about the housing se mentors right now who are all lection process and what is hap UNE students, and the group of TY GOWEN, NOR'EASTER NEWS pening next year. BUSH CENTER: George H.W. and Barbara Bush address UNE at the dedication ceremony on October 3, 2008. children they work with are any One of the first rumors is that where from kindergarten all the housing selection numbers are way to 8th grade. The age of the International Center not actually random. -

Congressional Correspondence

People Record 7006012 for The Honorable Peter T. King Help # ID Opened � WF Code Assigned To Template Due Date Priority Status 1 885995 11/3/2010 ESLIAISON4 (b)(6) ESEC Workflow 11/10/2010 9 CLOSED FEMA Draft Due to ESEC: 11/10/2010 ESEC Case Number (ESEC Use Only): 10-9970 To: Secretary Document Date: 10/25/2010 *Received Date: 11/03/2010 *Attachment: Yes Significant Correspondence (ESEC Use Only): Yes *Summary of Document: Write in support of the application submitted by the (b)(4) for $7,710,089 under the Staffing for Adequate Fire and Emergency Response grant program. *Category: Congressional *Type: Congressional - Substantive Issue *Action to be Taken: Assistant Secretary OLA Signature Status: Action: *Lead Component: FEMA *Signed By (ESEC Use Only): Component Reply Direct and cc: *Date Response Signed: 11/02/2010 Action Completed: 11/04/2010 *Complete on Time: Yes Attachments: 10-9970rcuri 10.25.10.pdf Roles: The Honorable Michael Arcuri(Primary, Sender), The Honorable Timothy H. Bishop(Sender) 2 884816 10/22/2010 ESLIAISON4 (b)(6) ESEC Workflow 11/5/2010 9 OPEN FEMA Reply Direct Final Due Date: 11/05/2010 ESEC Case Number (ESEC Use Only): 10-9776 To: Secretary Mode: Fax Document Date: 10/20/2010 *Received Date: 10/22/2010 *Attachment: Yes Significant Correspondence (ESEC Use Only): No *Summary of Document: Requests an Urban Area Security Initiative designation for seven southern San Joaquin Valley Counties. *Category: Congressional *Type: Congressional - Substantive Issue *Action to be Taken: Component Reply Direct and Cc: Status: