Tenncare II Demonstration Project No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

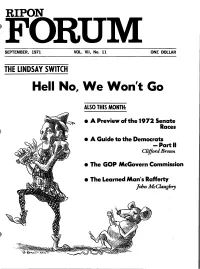

Hell No, We Won't Go

RIPON SEPTEMBER, 1971 VOL. VII, No. 11 ONE DOLLAR THE LINDSAY SWITCH Hell No, We Won't Go ALSO THIS MONTH: • A Preview of the 1972 Senate Races • A Guide to the Democrats -Partll Clifford Brown • The GOP McGovern Commission • The Learned Man's RaRerty John McClaughry THE RIPON SOCIETY INC is ~ Republican research and SUMMARY OF CONTENTS I • policy organization whose members are young business, academic and professional men and women. It has national headquarters In Cambridge, Massachusetts, THE LINDSAY SWITCH chapters in thirteen cities, National Associate members throughout the fifty states, and several affiliated groups of subchapter status. The Society is supported by chapter dues, individual contribu A reprint of the Ripon Society's statement at a news tions and revenues from its publications and contract work. The conference the day following John Lindsay's registration SOciety offers the following options for annual contribution: Con as a Democrat. As we've said before, Ripon would rather trtbutor $25 or more; Sustainer $100 or more; Founder $1000 or fight than switch. -S more. Inquiries about membership and chapter organization should be addressed to the National Executive Director. NATIONAL GOVERNING BOARD Officers 'Howard F. Gillette, Jr., President 'Josiah Lee Auspitz, Chairman 01 the Executive Committee 'lioward L. Reiter, Vice President EDITORIAL POINTS "Robert L. Beal. Treasurer Ripon advises President Nixon that he can safely 'R. Quincy White, Jr., Secretary Boston Philadelphia ignore the recent conservative "suspension of support." 'Martha Reardon 'Richard R. Block Also Ripon urges reform of the delegate selection process Martin A. LInsky Rohert J. Moss for the '72 national convention. -

A RESOLUTION to Honor the Memory of Mrs. Claire Caldwell Bawcom of Franklin

Filed for intro on 01/17/2002 SENATE RESOLUTION 115 By Blackburn A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of Mrs. Claire Caldwell Bawcom of Franklin. WHEREAS, it is fitting that the elected representatives of the State of Tennessee should pay tribute to those exemplary citizens who give unselfishly of themselves, their time, and their talents to perpetuate the public good; and WHEREAS, Mrs. Claire Caldwell Bawcom was most assuredly one such exemplary Tennessean deserving of praise and commendation for her political activism; and WHEREAS, she volunteered her time, working in various political activities, from 1976 to 2001; Mrs. Bawcom campaigned in 1976 for the election of Assemblyman John Dorsey in New Jersey, for Tennessee State Representative Cliff Frensley, for State Representative Clint Callicott, for President Ronald Reagan, for President George H. Bush, for State Senator Keith Jordan, for Juvenile Court Clerk Brenda Hyden, for Governor Don Sundquist, for Bob Dole for President, and for State Senator Marsha Blackburn; she also served as the Tennessee Co- Chairman for Jack Kemp's campaign for President; and WHEREAS, she was actively involved in Republican Women activities since 1990; she was a member of the Tennessee Federation of Republican Women, serving as Area 6B Vice SR0115 01034684 -1- President from 1991-95, as the Second Vice President from 1995-97, as the First Vice President from 1998-March 1999, and as the TFRW President from April 1999 until her death; and WHEREAS, she was actively involved in the Republican Women of Williamson -

Sa0839 015400 -1

Senate Transportation and Safety Committee 1 Amendment No. 4 to SB2694 Bailey Signature of Sponsor AMEND Senate Bill No. 2694 House Bill No. 1522* by deleting all language after the enacting clause and substituting instead the following: SECTION 1. (a) (1) Notwithstanding any law to the contrary, the segment of State Route 56 in the City of Gainesboro beginning from the intersection of such route with Hestand Lane to the intersection of such route with State Route 85, extending northeasterly along State Route 85/53, and ending at the intersection of State Route 53 with Dale Gaw Lane, is hereby designated the "Deputy Sheriff Zachary Larnerd Memorial Highway" in honor of this dedicated public servant of the City of Gainesboro and Jackson County, who was serving as a part-time police officer with the Gainesboro Police Department and a full-time deputy with the Jackson County Sheriff's Department when he made the ultimate sacrifice on June 15, 2016, when he passed away due to complications from injuries he sustained in a car accident while responding to a domestic violence call. (2) The department of transportation is directed to erect suitable signs or to affix suitable markers designating the segment described in subdivision (a)(1) as the "Deputy Sheriff Zachary Larnerd Memorial Highway". The cost of the signage shall be funded in accordance with Tennessee Code Annotated, Section 54-1-133. (3) The erection of the signs shall be within the guidelines prescribed by the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, and within state supplemental guidelines, as applicable. SA0839 015400 -1- Senate Transportation and Safety Committee 1 Amendment No. -

The Senate Legislative Manual

TENNESSEE SENATE 106TH GENERAL ASSEMBLY LEGISLATIVE MANUAL RON RAMSEY LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR AND SPEAKER OF THE SENATE Published by: The Office of the Chief Clerk Tennessee State Senate Russell Humphrey, Chief Clerk TABLE OF CONTENTS THE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH 3 The Lieutenant Governor ............................................................................... 4 Members of the Senate ................................................................................... 5 General Schedule ...........................................................................................15 Senate District Map .......................................................................................16 Senate Seating Chart......................................................................................17 Officers of the Senate.....................................................................................18 Sergeants-At-Arms........................................................................................19 Members of the House of Representatives.....................................................20 House District Map .......................................................................................24 House Seating Chart......................................................................................26 Senate Standing & Select Committees ..........................................................27 House Standing & Select Committees ..........................................................28 Joint Committees ...........................................................................................30 -

Vi. Tennessee's Auto Industry Future

DRIVE! MOVING TENNESSEE’S AUTOMOTIVE SECTOR UP THE VALUE CHAIN BROOKINGS ADVANCED INDUSTRIES SERIES Mark Muro, Scott Andes, Kenan Fikri, Martha Ross, Jessica Lee, Neil Ruiz, and Nick Marchio THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION | METROPOLITAN POLICY PROGRAM | 2013 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION | DRIVE! MOVING TENNESSEE’S AUTOMOTIVE SECTOR UP THE VALUE CHAIN TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ......................................................................................... i I. Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 II. Tennessee Shifts Into Drive ............................................................... 3 III. Measuring Tennessee’s Automotive Economy ............................. 6 IV. Opportunities and Threats: Key Forces at Work in the Global Auto Industry ....................................................................................... 21 V. Analyzing Strengths and Weaknesses: Tennessee’s Competitive Position ......................................................................... 30 VI. Tennessee’s Auto Industry Future: A Vision and Strategies for Getting There ...................................................................................... 50 VII. The Private Sector: Securing Advantage Through Productivity, Skills, and Innovation ........................................................................ 54 VIII. The Public Sector: Catalyzing Advances in Productivity, Skills Development, and Innovation ........................................................ -

A RESOLUTION to Honor Ms. Drue Smith and to Name the Press Room in the Legislative Plaza the "Drue Smith Press Suite."

Filed for intro on 04/05/2001 SENATE JOINT RESOLUTION 157 By Cohen A RESOLUTION To honor Ms. Drue Smith and to name the Press Room in the Legislative Plaza the "Drue Smith Press Suite." WHEREAS, For a number of years, Ms. Drue H. Smith has adroitly covered the political scene on Capitol Hill in Nashville; an employee of GCA Newspaper Publishing Company, Inc., Ms. Smith is the Capitol Hill correspondent for radio and television stations, both state-wide and network, and for the Green Hills, the Belle Meade, the West Meade, the West Side and the Nashville Today newspapers; and WHEREAS, Tommie Drue Henderson was born in Chattanooga to Jess and Sara Henderson, and was the only granddaughter of Andrew and Drue Muxen; and WHEREAS, Young Miss Henderson was raised in the tradition of Southern Ladies and was a graduate of the Girls' Preparatory School of Chattanooga; she continued her education at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. She married the late Roy Blaney Smith and became the mother of Drucilla Smith Fuller; and SJR0157 00515756 -1- WHEREAS, Ms. Smith began her career in journalism in Chattanooga as the Society Editor for both daily newspapers, the Chattanooga Times and the Chattanooga Free Press; she became known to many Tennesseans as an interviewer for numerous radio stations, including the Tennessee Radio Network, and for WDEF-TV Chattanooga, where she interviewed scores of famous people, including President John F. Kennedy; and WHEREAS, When she arrived in Nashville, Drue earned renown as a pioneer for women in her profession and in other areas; she was the first female admitted to the Society of Professional Journalists, and the first woman to occupy the office of Chair of the Capitol Hill Press Corps; she conducted a personal sit-in protest at a Nashville restaurant, the Gerst Haus, to allow unescorted women to eat at the counter; and WHEREAS, Ms. -

Bill Lee Tennessee Inauguration: Jan 2019 7 TN Next Election: 2022 State Control Party Governor Party Republican Republican OVERALL RANK

Bill Lee Tennessee Inauguration: Jan 2019 7 TN Next Election: 2022 State Control Party Governor Party Republican Republican OVERALL RANK PREVIOUS GOVERNORS AND PARTY AFFILIATION Results Rank (1=best, 50=worst): Bill Haslam 2011-2019 A situational measure based on Phil Bredesen 2003-2011 7 the state’s economic outcomes Don Sundquist 1995-2003 (equal-weighted average).These variables are highly influenced by Ned McWherter 1987-1995 the Governor’s policy. RESULTS RANK SENATE 15% 85% Policy Rank (1=best, 50=worst): Democrat 5 Republican 28 A Measure of policy stances and decisions based on each Governor’s 8 legislative history regarding 6 key HOUSE areas (equal-weighted average). 26% 74% POLICY RANK Democrat 26 Republican 73 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS RANK ABOUT GOVERNOR BILL LEE TAX POLICY Taking office in 2019, Governor Bill Lee presides as Sales, Personal Income, Fuel, and Other Tax Changes 24 Tennessee’s executive during one of the most vibrant periods of growth the state has seen. In fact, Tennessee’s economy is the eighth-strongest of any state. Despite SPENDING POLICY an influx of new tax dollars into the state, Gov. Lee has Proposed and Enacted Changes in State Spending 12 kept spending growth low. Reining in the growth of government also enabled Gov. Lee to enact net tax cuts in 2019 with the near-elimination of the professional licenses CARES POLICY tax, scaling back the amusement tax and the excepted Handling of Federal Funds as of July 2020 15 full phase out of the “Hall Tax” in January 2021. Once the Hall Tax on interest and dividend income is eliminated, Tennessee will officially have no tax on any form of UNION POLICY Public Employees, Public Employee Raises, personal income. -

Trends in Public Opinion, 1989-1996 John M

University of Dayton eCommons Political Science Faculty Publications Department of Political Science 1998 Trends in Public Opinion, 1989-1996 John M. Scheb II University of Tennessee - Knoxville William Lyons University of Tennessee - Knoxville Grant W. Neeley University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/pol_fac_pub Part of the American Politics Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Models and Methods Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons eCommons Citation Scheb, John M. II; Lyons, William; and Neeley, Grant W., "Trends in Public Opinion, 1989-1996" (1998). Political Science Faculty Publications. Paper 77. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/pol_fac_pub/77 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Political Science at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CHA.PTERll Trends in Public Opinion, 1989-1996 - John M. Scheb IL William Lyons, and Grant W Neeley He who writes of the state, of law, or of politics without first coming to close quarters with public opinion is simply evading the very central structure of his study. -Arthur Bentley, The Process of Government (1903) INTRODUCTION ''public opinion" consists of the measurable values, beliefs, attitudes, and opinions of the mass public. Nearly all political scientists, following Arthur Bentley, recognize the importance of public opinion in politics and the policy process. 1 While it is true that much of the stuff of public opinion is unstable or even ephemeral, some elements of public opinion not only endure but also reveal political preferences and behavior. -

1999 NGA Annual Meeting

•• NATIONALGOVERNORS' ASSOCIATION 91st Annual Meeting August 8, 1999 The Adam's Mark Hotel St. Louis, Missouri REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS PLENARYSESSION • SPEAKERS: Senator Don Nickles 22 President William Jefferson clinton 66 Rероrtеd Ву: Debra М. Musielak, CSR, RDR Rankin Reporting & Legal Video, Inc. , 1015 Locust Street, Suite 911 • St. Louis, МО 63101 1 1 August 8, 1999 • 2 3 PLENARYSESSION 4 5 CНAIRМANCARPER: Ladies and gentlemen, would 6 уои Ьеgin taking your seats, please? I'd especially 7 appreciate Governors beginning to take their seats. And I 8 would especially appreciate Governor Carnahan joining те hеrе 9 at the front of the room. And if somebody could make sure 10 that our host, Governor -- ah, here he comes, Governor 11 Carnahan. Let's give Governor Carnahan а rеаl big round of 12 applause. Thank уои vеrу much for letting us соте to your 13 state, the "Show Ме Stаtе." • 14 (applause) 15 CНAIRМANCARPER: Before I call оп Gоvеrnоr 16 Carnahan, let те just welcome each and every опе of уои to 17 this the 91st Annual Meeting of the National Governors' 18 Association. I'm tempted to ask those of уои in the audience 19 who were at the first опе to raise your hand. There might Ье 20 опе or two. And we've met some veteran Governors here who've 21 соте Ьасk to join this group. And nobody from the first 22 meeting. But we've had some who were Governors as far back 23 as 1965, and it's Ьееп grеаt to see them. 24 We're going to Ье jоinеd shortly Ьу two very • 25 sресiаl guests, Senator Don Nickles of Oklahoma, and we'll Ье 2 1 joined Ьу thе President of the United States for some remarks • 2 from the executive branch and from the legislative branch of 3 our country. -

Governor's Executive Orders, 1953-Present

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 EXECUTIVE ORDERS OF THE GOVERNORS OF TENNESSEE 1953-1996 RECORD GROUP 95 Processed by: Michael D. Trent, David R. Sowell Archival Technical Services Microfilmed up to: June 2, 1996 MICROFILMED SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Record Group 95 consists of the Executive Orders from the following Tennessee Governors: Frank G. Clement (1953-1955; 1956-1958; 1963-1966), Buford Ellington (1959-1962; 1967-1970), Winfield Dunn (1971-1974), Ray Blanton (1975-1978), Lamar Alexander (1979-1986), Ned Ray McWherter (1987-1995) and Don Sundquist (1995- 2003). Executive Orders allow the Governor of the State to have a more direct role in the policy-making process of State Government. Questions have been raised concerning the Governor’s constitutional power to issue such orders. Article III, Section I of the Tennessee Constitution (1870) states that “the Supreme Executive power of this State shall be vested in a Governor.” The Supreme Court has stated that executive power is the authority to administer and enforce the law. The State Constitution fails to give a specific definition of executive powers. Executive Orders deal primarily with appropriations, creation of state agencies, appointments, etc. Very rarely does the Executive issue and order activating the Tennessee National Guard. A list of each Executive Order and its purpose has been enclosed. CONTAINER LIST ORDER # DESCRIPTION Series Number: 1 Series Title: Frank G. Clement First Term 1953-1955 Box 1 1 Appropriation – Special Breed Shows – Polled Hereford Shoe in Knoxville 2 Appropriation – Tennessee School for the Deaf 3 Appropriation – Expenses incurred by the Governor’s Official Party to President Eisenhower’s Inauguration 4 Appropriation – Purchase of land adjoining James K. -

Tennessee State Library and Archives SECRETARY of STATE

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 SECRETARY OF STATE FEDERAL CAMPAIGN DISCLOSURE STATEMENTS 1974-1989 RECORD GROUP 193 Processed by: Greg Yates Archives and Manuscripts Unit Technical Services Section Date Completed: January 30, 1992 MICROFILM ONLY Microfilm Roll # 1 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Record Group 193, Federal Campaign Disclosure Statements, covers the period 1974- 1989. The group consists of Financial Disclosure Statements and Campaign reports of receipts and disbursements as are required under federal rules and regulations. These reports are filed with the Federal Election Commission and also with the State Elections Division. The collection consists of Presidential Disclosure Statements, U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives disclosures, concentrating on activities in Tennessee and candidates from Tennessee. Accompanying the statements are supporting schedules that describe in detail each section of the statements. Record Group 193, Federal Campaign Statements, is an interesting way to look into the funding process of seeking election to public office. Following the Series Index is a Name Index of all candidates included in the collection. NAME INDEX Following is a Name Index for the Federal Campaign Disclosure Statements. Adams, Michael F. Box 12 Albright, Raymond C. Box 12 Algood, Alice Box 8 Allen, Clifford Box 9 Anderson, William E. Box 8, Box 12 Arline, Clarence Ronald Box 9 Ashe, Victor Henderson Box 8 Baker, Cynthia Box 13 Baker, Jr., Howard H. Box 8 Ball, William Gordon Box 9 Barker, Dorothy Nelson Box 9 Barnett, Frank Elliot Box 8 Bates, Charles Larry Box 9 Bates, Mark-Clark Box 9 Bays, Jr., Nathaniel Martin Box 13 Beard, Jr., Robin Leo Box 13 Benson, Bruce Edward Box 13 Biden, Joe Box 4 Bissell, Keith Box 9 Blanton, Ray Box 9 Bloodworth, Kenneth Wayne Box 9 Boner, William Hill Box 9 Bowen, John F. -

A Master Plan for the Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area

A Master Plan for the Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area Prepared by the Center for Historic Preservation, Middle Tennessee State University October 2001 2 Table of Contents 1. Project Background 2. Public Participation 3. Partnerships within the Master Planning Process and with the Management Entity 4. Master Plan: Themes and Initial Projects 5. Appendices I. Compact for the Tennessee Civil War Heritage Area II. Copies of Returned Survey Forms from Public Meeting Participants III. Copies of Website Comments and Suggestions IV. Selected News and Feature Stories 3 I. Project Background and History In 1995 Congress invited proposals from across the United States for the National Heritage Areas program of the National Park Service. A total of forty-one states submitted proposals and eight were ultimately selected, including Tennessee’s application for a statewide Civil War Heritage Area prepared by the Middle Tennessee State University’s Center for Historic Preservation (CHP) with the assistance of Congressman Bart Gordon. On November 12, 1996, Congress passed Public Law 104-333, which authorized the creation of the Tennessee Civil War Heritage Area. Tennessee, thus, became part of a select group of regions across the country where a federal, state, local, and private partnership coordinate ways to preserve, interpret, and enhance valuable historical and cultural resources. The Tennessee Civil War Heritage Area is one of eighteen congressionally designated heritage areas across the country that represent stories, people, and places of national significance. The National Heritage Areas are: 1. Augusta Canal (Georgia) 2. Automobile Heritage (Michigan) 3. Blackstone River Valley Corridor (Massachusetts and Rhode Island) 4.