An Examination of Tennessee Gubernatorial Elections, 1932-2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[D) [E ~ A[Rfim [EU\J]1 of (CO[R{R[E(Cl~O~](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3054/d-e-a-rfim-eu-j-1-of-co-r-r-e-cl-o-183054.webp)

[D) [E ~ A[Rfim [EU\J]1 of (CO[R{R[E(Cl~O~

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. If[E~~][E~~[E[E [D) [E ~ A[RfiM [EU\J]1 Of (CO[R{R[E(cl~O~ co o N , Fiscal Year 1992-93 Annual Report Ned McWherter, Governor Christine J. Bradley ~ Commissioner ------------------------------------------------------------------ 151208 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted matarial has been granted by Tennessee Deparl::1.1Ent of Corrections to tha National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. ------------------------ ---------------------------------.-------------------------------------------------------------------------- Fiscal Year 1992-93 Annual Report Planning and Research Section July 1994 STATE OF TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTION FOURTH FLOOR, RACHEL JACKSON BUILDING· NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE 37243-0465 CHRISTINE J. BRADLEY COMMISSIONER July 5,1994 The Honorable Ned McWherter Governor of Tennessee and The General Assembly State of Tennessee Ladies and Gentlemen: Fiscal Year 1992-93 marked the end of an era for the Tennessee Department of Correction. On May 14, 1993, the department was released from a lengthy period of federal court supervision brought about by the Grubbs suit. Since the court order and the special session of the General Assembly in 1985, the department has made noticeable, significant advancements it the management of its operations. The final Grubbs order reflects the court's concurrence with these advancements. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS December 11, 1973 the "Gerald R

40896 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS December 11, 1973 the "Gerald R. Ford Federal Office Building"; TAYLOR of North Carolina, Mr. KET By Mr. PICKLE (for himself, Mr. Mc to the Committee on Public Works. cHuM, Mr. DERWINSKI, Mr. MANN, CoLLISTER, Mr. MONTGOMERY, 1\11'. By Mrs. HOLT: Mr. DAVIS of Georgia, Mr. YATRON 0 KEMP, Mr. SPENCE, Mr. BURGENER, H.R. 11899. A bill to provide retirement an Mr. NICHOLS, Mr. ANDREWS of North Mr. COCHRAN, Mr. DON H. CLAUSEN, nuities for certain widows of membera of the Dakota, Mr. MONTGOMERY, Mr. LoTT, Mr. RANGEL, Mr. HUBER, Mr. SCHERLE, uniformed services who died before the ef Mr. McCoLLISTER, Mr. JoHNSON of Mr. QUIE, Mr. KETCHUM, Mr. ADDAB fective date of the Survivor Benefit Plan; to Pennsylvania, Mr. BENNETT, and Mr. BO, Mr. McEWEN, Mr. BoB WILSON, the Committee on Armed Services. MORGAN); Mr. RoBINSON of Virginia, Mr. WoN H .R. 11900. A bill to require that a per H.R. 11905. A bill to amend the Internal PAT, Mr. EILBERG, Mr. RoE, Mr. TREEN, centage of U.S. oil imports be carried on U.S.· Revenue Code of 1954 to provide that the Mr. ROUSSELOT, Mr. HUDNUT, Mr. flag vessels; to the Committee on Merchant tax on the amounts paid for communication STEELMAN, and Mr. MAZZOLI); Marine and Fisheries. services shall not apply to the amount of H.J. Res. 853. Joint resolution expressing By Mrs. HOLT (for herself and Mr. the State and local taxes paid for such serv the concern of the United States about Amer HOGAN); ices; to the Committee on Ways and Means. -

June 11, 2018.Indd

6,250 subscribers www.TML1.org Volume 69, Number 10 June 11, 2018 Free Conference mobile app available Connects to all smartphone devices June 9 - 12 in Knoxville A mobile app featuring the an event will reveal a description; 2018 Annual Conference infor- and if it’s a workshop, speaker bios mation is available for free and is are also available. As an added New sessions added to accessible from any smart phone feature, you can create your own device. personal schedule by touching the Annual Conference lineup The app was developed by plus symbol next to events. You Protecting the availability of the Tennessee Municipal League can also set reminders for yourself. a clean and reliable water supply to help improve smartphone us- Conference events are color-coded in Tennessee is vital to support ers conference experience with by each event type. By using the fil- the state’s growing population and this easy to use digital guide. It ter button at the top to apply a filter, sustain economic growth. contains detailed conference in- you can quickly reference catego- Deputy Governor Jim Henry formation on workshops, speakers, ries such as food, workshops, or and TDEC Commissioner Shari exhibitors and special events – and special events. Meghreblian will help kickoff a it’s all at your fingertips. Speakers. To learn about each panel of local government officials To download the free app, of our conference speakers, scroll and industry leaders to discuss it’s as easy as searching for “2018 through the list and tap on the concerns about the state’s aging TML Annual Conference” in the speaker’s photo to reveal their bios. -

League Launches Advocacy Initiative by CAROLE GRAVES TML Communications Director

1-TENNESSEE TOWN & CITY/JANUARY 29, 2007 www.TML1.org 6,250 subscribers www.TML1.org Volume 58, Number 2 January 29, 2007 League launches advocacy initiative BY CAROLE GRAVES TML Communications Director The Tennessee Municipal League has launched a new advo- cacy program called “Hometown Connection.” The mission of the program is to foster better relation- ships between city officials and their legislators and enhance the League’s advocacy efforts on Capi- tol Hill. TML’s Hometown Connection will provide many resources to help city officials stay up-to-date on leg- islative activities, as well as offer more opportunities for the League’s members to become more involved in issues affecting municipalities Among the many resources at their disposal are: • Legislative Bulletins • Action Alerts • Special Committee Lists Photo by Victoria South • TML Web Site and the Home- town Connection Ceremony marks Governor Bredesen’s second term • District Directors’ Program With First Lady Andrea Conte by his side, Gov. Phil Bredesen took the oath of office for his second term as the 48th Govornor of Tennessee • Hometown Champions before members of the Tennessee General Assembly, justices of the Tennessee Supreme Court, cabinet staff, friends, family and close to 3,000 • Hometown Heroes Tennesseans. The inauguration ceremony took place on War Memorial Plaza in front of the Tennessee State Capitol. After being sworn in, • Legislative Contact Forms Bredesen delivered an uplifting 12-minute address focusing on education in Tennessee as his number one priority along with strengthening • Access to Legislators’ voting Tennessee’s families. Bredesen praised Conte as an “amazing” first lady highlighting her efforts to help abused children by treking 600 miles record on key municipal issues across Tennessee and thanked her for “32 years of love and friendship.” Entertaining performances included the Tennessee National Guard • Tennessee Town and City Band and the Tennessee School for the Blind’s choral ensemble. -

The Other Side of the Monument: Memory, Preservation, and the Battles of Franklin and Nashville

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MONUMENT: MEMORY, PRESERVATION, AND THE BATTLES OF FRANKLIN AND NASHVILLE by JOE R. BAILEY B.S., Austin Peay State University, 2006 M.A., Austin Peay State University, 2008 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2015 Abstract The thriving areas of development around the cities of Franklin and Nashville in Tennessee bear little evidence of the large battles that took place there during November and December, 1864. Pointing to modern development to explain the failed preservation of those battlefields, however, radically oversimplifies how those battlefields became relatively obscure. Instead, the major factor contributing to the lack of preservation of the Franklin and Nashville battlefields was a fractured collective memory of the two events; there was no unified narrative of the battles. For an extended period after the war, there was little effort to remember the Tennessee Campaign. Local citizens and veterans of the battles simply wanted to forget the horrific battles that haunted their memories. Furthermore, the United States government was not interested in saving the battlefields at Franklin and Nashville. Federal authorities, including the War Department and Congress, had grown tired of funding battlefields as national parks and could not be convinced that the two battlefields were worthy of preservation. Moreover, Southerners and Northerners remembered Franklin and Nashville in different ways, and historians mainly stressed Eastern Theater battles, failing to assign much significance to Franklin and Nashville. Throughout the 20th century, infrastructure development encroached on the battlefields and they continued to fade from public memory. -

State Banking on Financial Literacy New Model Debt Policy Released; Deadline for Public Input Sept 15

1-TENNESSEE TOWN & CITY/AUGUST 23, 2010 www.TML1.org 6,250 subscribers www.TML1.org Volume 61, Number 14 August 23, 2010 Haslam, McWherter to face off in November GOP candidate Knoxville Mayor Bill Haslam prevailed in a three-way Republican primary race for governor. He won with 47 percent of votes, followed by 3rd District U.S. Rep. Zach Wamp in second place with almost 30 percent and Lt. Governor Ron Ramsey in third with 22 percent. Save the Dates! Meanwhile, West Tennessee businessman Mike McWherter is uncontested on the Demo- TML Annual Conference cratic side. He was unopposed after four Democratic opponents withdrew from the race. The two candidates will square off in three June 12 - 14, 2011 gubernatorial debates planned for this fall with the first scheduled for Sept. 14 in Cookeville. Congress Murfreesboro Convention Center Several Congressional races were also hotly contested. In District 9, incumbent Steve Cohen easily won his democratic primary over New Model Debt Policy former Memphis Mayor Willie Herenton. Cohen received 79 percent of the vote over GOP candidate Knoxville Herenton’s 21 percent. Mayor Bill Haslam will released; deadline for GOP challengers battled it out in District 8, face Democratic nomi- with Stephen Fincher winning the primary with nee Mike McWherter in 48.5 percent over Ron Kirkland’s 24.4 percent the November general public input Sept 15 and George Flinn’s 24 percent. Fincher will election, to determine face state Sen. Roy Herron, the Democratic who will serve as the 49th State Comptroller Justin Wilson Tennessee governmental debt issu- nominee, in the general election for the chance Governor of Tennessee. -

Tennessee Civil and Military Commissions 1796-1976 Record Group 195

TENNESSEE CIVIL AND MILITARY COMMISSIONS 1796-1976 RECORD GROUP 195 Processed by: Ted Guillaum Archival Technical Services Date Completed: 2-28-2002 MICROFILMED INTRODUCTION Record Group 195, Tennessee Civil and Military Commissions, 1796-1976, contains the records of the commissions made by the governors of Tennessee. The commissions measure seven and ½ cubic feet and are recorded in 56 volumes. These records were maintained by the Secretary of State and were found to be in fair to good condition. Many of the earlier volumes required light cleaning of accumulated soot. Fifteen volumes were found to be in fragile condition and were placed in acid free boxes for their protection. Portions of these records were received from the Records Center at various times between 1973 and 1994. There are no restrictions on the use of these records. The volumes have been arranged chronologically and have been microfilmed. The original documents have been retained. SCOPE AND CONTENT Tennessee Civil and Military Commissions, 1796-1976, record the appointments by the governors of Tennessee to various positions of authority in the state. Tennessee's chief executive used commissions to confer positions of military and civil authority on various individuals. These records were kept and maintained by the Secretary of State. The commissions found in these volumes can include Military Officer, Judge, Attorney, Sheriff, Coroner, Justice of the Peace, Surveyor, Road Commissioner, Turnpike Operators, Attorney General, Solicitor General, Electors for President and Vice- President, Indian Treaty Delegates, State Boundary Line Dispute Delegates, Trustees to the Lunatic Asylum and Institution for the Blind, Inspectors of Tobacco and the Penitentiary, State Agricultural Bureau, Assayer, Superintendent of Weights and Measurers, Geologist & Mineralogist, Railroad Directors, and Bonding Regulators. -

Aug 3, 2006 Election Results

Aug 3, 2006 Election Results Race Primary Candidates Paper Absentee Early ElectionTotal Votes GOVERNOR DEM Phil Bredesen 0 75 746 2366 3187 DEM John Jay Hooker 0 13 24 128 165 DEM Tim Sevier 0 3 11 63 77 DEM Walt Ward 0 1 10 30 41 UNITED STATES SENATE DEM Gary G. Davis 0 13 45 178 236 DEM Harold Ford, Jr. 0 50 671 2115 2836 DEM John Jay Hooker 0 13 29 116 158 DEM Charles E. Smith 0 3 21 69 93 DEM Al Strauss 0 2 3 20 25 UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2nd Congressional District DEM John Greene 0 35 353 1041 1429 DEM Robert R. Scott 0 25 223 740 988 STATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEEMAN 8th Senatorial District DEM Daniel J. Lawson 0 56 488 1355 1899 GOVERNOR REP Mark Albertini 0 11 126 321 458 REP Wayne Thomas Bailey 0 14 128 343 485 REP Jim Bryson 0 42 845 2193 3080 REP David M. Farmer 0 21 256 813 1090 REP Joe Kirkpatrick 0 16 202 687 905 REP Timothy Thomas 0 4 82 258 344 REP Wayne Young 0 14 123 481 618 UNITED STATES SENATE REP Ed Bryant 0 31 747 2354 3132 REP Bob Corker 1 89 1516 4275 5881 REP Tate Harrison 0 5 27 140 172 REP Van Hilleary 1 66 376 1376 1819 UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 2nd Congressional District REP John J. Duncan, Jr. 2 173 2324 7159 9658 REP Ralph McGill 0 22 318 936 1276 TENNESSEE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 8th Representative District REP Joe McCord 1 37 875 3085 3998 TENNESSEE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 20th Representative District REP Doug Overbey 1 122 1460 3974 5557 STATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEEMAN 8th Senatorial District REP Thomas E. -

Tenncare II Demonstration Project No

Tennessee Department of Finance & Administration Division of TennCare TennCare II Demonstration Project No. 11-W-00151/4 Extension Application DRAFT November 9, 2020 Table of Contents Section I: Historical Narrative Summary of TennCare II ..............................................................................1 Section II: Narrative Description of Changes Being Requested ............................................................... 11 Section III: Requested Waiver and Expenditure Authorities ................................................................... 14 Section IV: Summaries of EQRO Reports, MCO and State Quality Assurance Monitoring, and Other Documentation of the Quality of and Access to Care Provided Under the Demonstration ................................................................................................... 14 Section V: Financial Data .......................................................................................................................... 20 Section VI: Draft Interim Evaluation Report ............................................................................................ 21 Section VII: Documentation of the State’s Compliance with the Public Notice Process ................................................................................................................................................ 21 Appendices Appendix A: Key TennCare II Leaders Appendix B: Draft Interim Evaluation Report Appendix C: Data on Medication Therapy Management Program Appendix D: Projected Expenditures -

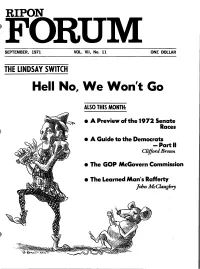

Hell No, We Won't Go

RIPON SEPTEMBER, 1971 VOL. VII, No. 11 ONE DOLLAR THE LINDSAY SWITCH Hell No, We Won't Go ALSO THIS MONTH: • A Preview of the 1972 Senate Races • A Guide to the Democrats -Partll Clifford Brown • The GOP McGovern Commission • The Learned Man's RaRerty John McClaughry THE RIPON SOCIETY INC is ~ Republican research and SUMMARY OF CONTENTS I • policy organization whose members are young business, academic and professional men and women. It has national headquarters In Cambridge, Massachusetts, THE LINDSAY SWITCH chapters in thirteen cities, National Associate members throughout the fifty states, and several affiliated groups of subchapter status. The Society is supported by chapter dues, individual contribu A reprint of the Ripon Society's statement at a news tions and revenues from its publications and contract work. The conference the day following John Lindsay's registration SOciety offers the following options for annual contribution: Con as a Democrat. As we've said before, Ripon would rather trtbutor $25 or more; Sustainer $100 or more; Founder $1000 or fight than switch. -S more. Inquiries about membership and chapter organization should be addressed to the National Executive Director. NATIONAL GOVERNING BOARD Officers 'Howard F. Gillette, Jr., President 'Josiah Lee Auspitz, Chairman 01 the Executive Committee 'lioward L. Reiter, Vice President EDITORIAL POINTS "Robert L. Beal. Treasurer Ripon advises President Nixon that he can safely 'R. Quincy White, Jr., Secretary Boston Philadelphia ignore the recent conservative "suspension of support." 'Martha Reardon 'Richard R. Block Also Ripon urges reform of the delegate selection process Martin A. LInsky Rohert J. Moss for the '72 national convention. -

Endquerynov19.XLSX

11/30/19 Market Account Value Pooled Number Account Name 11/30/19 Book Value Assets F010000001 Land Grant Endowment 400,000.00 0.00 F010000002 Reserve for Loss on Land Grant Endowment 69,697.50 0.00 F010000003 Norman B. Sayne Library Endowment-Humanities 776.54 2,438.43 F010000004 John L.Rhea Library Endowment-Classical Literature 9,518.51 31,379.69 F010000005 Lalla Block Arnstein Library Endowment 5,149.94 17,227.08 F010000006 James Douglas Bruce Library Endowment-English 5,120.00 17,077.22 F010000007 Angie Warren Perkins Library Endowment 1,738.94 5,822.59 F010000008 Stuart Maher Endowment for Technical Library 1,620.81 4,659.33 F010000009 J. Allen Smith Library Endowment 1,102.01 3,678.07 F010000010 Oliver Perry Temple Endowment 24,699.71 82,357.82 F010000011 George Martin Hall Memorial Endowment-Geology 15,307.17 32,507.34 F010000012 Eleanor Dean Swan Audigier Endowment 75,620.98 221,689.58 F010000013 Nathan W. Dougherty Recognition Endowment 23,445.60 57,119.42 F010000014 Better English Endowment 7,018,636.44 12,536,611.52 F010000015 Walters Library Endowment 2,200.00 8,393.10 F010000017 Mamie C. Johnston Library Endowment 5,451.77 18,124.66 F010000018 Ira N. Chiles Library Endowment-Higher Education 21,039.50 58,490.04 F010000019 Human Ecology Library Development Endowment 18,876.01 57,253.50 F010000020 Ellis and Ernest Library Endowment 9,126.87 27,236.56 F010000021 Hamilton National Bank Library Endowment 7,211.34 24,278.80 F010000022 Charles I. -

Cabinet Room #55: April 20

1 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. 10/08) Conversation No. 55-1 Date: April 20, 1971 Time: 5:17 pm - 6:21 pm Location: Cabinet Room The President met with Barry M. Goldwater, Henry L. Bellmon, John G. Tower, Howard H. Baker, Jr., Robert J. Dole, Edward J. Gurney, J. Caleb Boggs, Carl T. Curtis, Clifford P. Hansen, Jack R. Miller, Clark MacGregor, William E. Timmons, Kenneth R. BeLieu, Eugene S. Cowen, Harry S. Dent, and Henry A. Kissinger [General conversation/Unintelligible] Gordon L. Allott Greetings Goldwater Tower Abraham A. Ribicoff [General conversation/Unintelligible] President’s meeting with John L. McClellan -Republicans -John N. Mitchell -Republicans -Defections -National defense -Voting in Congress National security issues -Support for President -End-the-war resolutions -Presidential powers -Defense budget -War-making powers -Jacob K. Javits bill -John Sherman Cooper and Frank F. Church amendment -State Department 2 NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF Tape Subject Log (rev. 10/08) -Defense Department -Legislation -Senate bill -J. William Fulbright -Vice President Spiro T. Agnew -Preparedness -David Packard’s speech in San Francisco -Popular reaction -William Proxmire and Javits -Vietnam War ****************************************************************************** BEGIN WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 [National Security] [Duration: 7m 55s ] JAPAN GERMANY AFRICA SOVIET UNION Allott entered at an unknown time after 5:17 pm END WITHDRAWN ITEM NO. 1 [To listen to the segment (29m15s) declassified on 02/28/2002,