Volunteer Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NX Wind PLUS

NX Wind PLUS - Instrument - Installation and Operation Manual English WIND English 1 English WIND 1 Part specification .............................................................................................. 3 2 Installation ......................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Installing the instrument ..................................................................................... 6 2.1.1 Installing the instrument to the WSI-box ................................................... 7 2.1.2 Installing the instrument to the NX2 Server ............................................... 8 2.1.3 Connecting to another Nexus instrument. ................................................. 8 3 First start (only in a Nexus Network) ............................................................... 8 3.1 Initialising the instrument ................................................................................... 8 3.2 Re-initialising the instrument .............................................................................. 9 4 Operation ......................................................................................................... 10 4.1 How to use the push buttons ........................................................................... 10 4.1.1 Lighting ................................................................................................... 11 4.2 Main function .................................................................................................. -

Seneca Lock, Chesapeake and Ohio

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2010 Seneca Lock Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Seneca Lock Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national -

BILGE PUMPING ARRANGEMENTS MSIS27 CHAPTER 5 Rev 09.21

INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE GUIDANCE OF SURVEYORS ON BILGE PUMPING ARRANGEMENTS MSIS27 CHAPTER 5 Rev 09.21 Instructions to Surveyors – Fishing Vessels Bilge Pumping Document Amendment History PREFACE 0.1 These Marine Survey Instructions for the Guidance of Surveyors (MSIS) are not legal requirements in themselves. They may refer to statutory requirements elsewhere. They do represent the MCA policy for MCA surveyors to follow. 0.2 If for reasons of practicality, for instance, these cannot be followed then the surveyor must seek at least an equivalent arrangement, based on information from the owner/operator. Whenever possible guidance should be sought from either Principal Consultant Surveyors or Survey Operation Branch, in order to maintain consistency between Marine Offices. UK Maritime Services/Technical Services Ship Standards Bay2/22 Spring Place 105 Commercial Road Southampton SO15 1EG MSIS 27.5 R09.21/Page 2 of 16 Instructions to Surveyors – Fishing Vessels Bilge Pumping Document Amendment History RECENT AMENDMENTS The amendments made in the most recent publication are shown below, amendments made in previous publications are shown in the document Amendment History. Version Status / Change Date Author Content Next Review Number Reviewer Approver Date/Expiry Date 10.20 • Add requirement that 20/10/20 D Fenner G Stone 20/10/22 bilge sensors in compartments containing pollutants shall not automatically start bilge pumps • Requirements for supply of powered bilge starting arrangements through separate switchboard updated. • Main watertight compartment is defined 09.21 • Amendments to reflect 31/8/2021 D Fenner G Stone 31/8/23 publication of MSN1871 Amendment No.2 MSIS 27.5 R09.21/Page 3 of 16 Instructions to Surveyors – Fishing Vessels Bilge Pumping Document Amendment History PREFACE ....................................................................................................... -

Public Access Points Within 50 Miles of Capitol Hill

Public Access Points within 50 Miles of Capitol Hill Public Access Point Boat Ramp Fishing Swimming Restrooms Hiking/Trekking Location 2900 Virginia Ave NW, Thompson's Boat Center X X X X Washington, DC 20037 3244 K St NW, Washington, DC Georgetown Waterfront Park X X 20007 George Washington Memorial Theodore Roosevelt Island X X X Pkwy N, Arlington, VA 22209 West Basin Dr SW, Washington, West Potomac Park X X DC 20024 Capital Crescent Trail, Washington Canoe Club X Washington, DC 20007 600 Water St SW, Washington, DC Ganglplank Marina X X X X 20024 George Washington Memorial Columbia Island Marina X X X Parkway, Arlington, VA 22202 99 Potomac Ave. SE. Washington, Diamond Teague Park X X DC 20003 335 Water Street Washington, DC The Yards Park X 20003 Martin Luther King Jr Ave SE, Anacostia Boat House X Washington, DC 20003 700-1000 Water St SW, Washington Marina X X X X Washington, DC 20024 Anacostia Park, Section E Anacostia Marina X X X Washington, DC 20003 2001-2099 1st St SW, Washington, Buzzard's Point Marina X X X DC 20003 2038-2068 2nd St SW, James Creek Marina X X X Washington, DC 20593 Anacostia Dr, Washington, DC Anacostia Park X X X 20019 Heritage Island Trail, Washington, Heritage Island X DC 20002 Kingman Island Trail, Washington, Kingman Island X DC 20002 Mt Vernon Trail, Arlington, VA Gravelly Point X X 22202 George Washington Memorial Roaches Run X X X X Pkwy, Arlington, VA 22202 1550 Anacostia Ave NE, Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens/Park X X X Washington, DC 20019 Capital Crescent Trail, Jack's Boat House X X Washington, DC 20007 Daingerfield Island X X X X 1 Marina Dr, Alexandria, VA 22314 67-101 Dale St, Alexandria, VA Four Mile Run Park/Trail X X X 22305 4601 Annapolis Rd. -

Cargo Hold Bilge Wells

AMVP INSPECTION MANUAL BILGE STRUM BOX OR EQUIVALENT MISSING ITEM: CARGO HOLD BILGE WELLS FINDING: BILGE STRUM BOX OR EQUIVALENT MISSING Strum box Bilge well without strum box Strainer plate on top of bilge Strum box equivalent or strainer well (also strum box fitted) WHY IS THIS A PROBLEM? TECHNICAL DATA: BILGE STRUM BOX OR EQUIVALENT • The bilge suction line is normally fitted with a perforated strum box around the suction which prevents cargo debris from entering the bilge line • This is not to be confused with a strainer plate on top of the bilge well (see photos) • Some bilges are provided with a two-compartment system: one bilge well with a perforated cover (strainer) and one with a full cover. Between the two compartments there is an opening to allow water to overflow, which can also be fitted with a perforated plate to prevent debris from entering the bilge line ISSUE WHEN NO PROTECTION IS FITTED • When no protection is provided for the bilge suction, any debris can enter the suction line and cause clogging (impair suction) or get stuck in the non-return system on the bilge line (cause backflow) IMCS BVBA – SHIP INSPECTION DEPARTMENT – [email protected] - WWW.IMCS-GROUP.COM PAGE 1/2 AMVP INSPECTION MANUAL BILGE STRUM BOX OR EQUIVALENT MISSING WHAT KIND OF FEEDBACK IS EXPECTED? CORRECTIVE ACTION • If spare parts are installed: order note or photograph of installation PREVENTIVE MEASURES • Explanation of your protection in place. This can be physical or procedural IMCS BVBA – SHIP INSPECTION DEPARTMENT – [email protected] - WWW.IMCS-GROUP.COM PAGE 2/2 . -

LEXIQUE NAUTIQUE ANGLAIS-FRANÇAIS – 2E ÉDITION, NUMÉRIQUE, ÉVOLUTIVE, GRATUITE

Aa LEXIQUE NAUTIQUE ANGLAIS-FRANÇAIS – 2e ÉDITION, NUMÉRIQUE, ÉVOLUTIVE, GRATUITE « DIX MILLE TERMES POUR NAVIGUER EN FRANÇAIS » ■ Dernière mise à jour le 19 octobre 2017 ■ Présenté sur MS Word 2011 pour Mac ■ Taille du fichier 2,3 Mo – Pages : 584 - Notes de bas de page : 51 ■ Ordre de présentation : alphabétique anglais ■ La lecture en mode Page sur deux colonnes est recommandée Mode d’emploi: Cliquer [Ctrl-F] sur PC ou [Cmd-F] sur Mac pour trouver toutes les occurrences d’un terme ou expression en anglais ou en français AVERTISSEMENT AUX LECTEURS Ouvrage destiné aux plaisanciers qui souhaitent naviguer en français chez eux comme à l’étranger, aux instructeurs, modélistes navals et d’arsenal, constructeurs amateurs, traducteurs en herbe, journalistes et adeptes de sports nautiques et lecteurs de revues spécialisées. Il subsiste moult coquilles, doublons et lacunes dont l’auteur s’excuse à l’avance. Des miliers d’ajouts et corrections ont été apportés depuis les années 80 et les entrées sont dorénavant accompagnées d’un ou plusieurs domaines. L’auteur autodidacte n’a pas fait réviser l’ouvrage entier par un traducteur professionnel mais l’apport de généreux plaisanciers, qui ont fait parvenir corrections et suggestions depuis plus de trois décennies contribue à cet ouvrage offert gracieusement dans un but strictement non lucratif, pour usage personnel et libre partage en ligne avec les amoureux de la navigation et de la langue française. Les clubs et écoles de voile sont encouragés à s’en servir, à le diffuser aux membres et aux étudiants. Tous droits réservés de propriété intellectuelle de l’ouvrage dans son ensemble (Copyright 28.10.1980 Ottawa); toutefois la citation de courts extraits est autorisée et encouragée. -

Ockam System Manual

OCKAM SYSTEM MANUAL Edition of February 17, 2009 Copyright © 1984-2009 by Ockam Instruments, Inc., All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America Ockam Instruments Inc. 215 Research Drive Milford, CT 06460 (203) 877-7453 (203) 878-0572 (Fax) http://www.ockam.com Revised 2/17/09 PAGE 1 READ THIS FIRST Thank you for considering Ockam Instruments, the world’s best sailing instrument system. Sailboat instruments, like the boats they go on are at least semi-custom products. Each installation will differ from others in capability and features. Ockam uses a modular approach to allow the greatest flexibility in capability. A professional electronics expert is usually needed to properly design, install and set up the system. • To read a description of the Ockam Instrument system, read Sections 1 & 2. • For installation, read Section 3. • Calibration? Go to Section 3 - Calibration. • Got a problem with the system? Go to Section 3 - Troubleshooting. Page 2 Revised 2/17/09 Table of Contents Section 1 - System Architecture.................................................................................................11 Systems................................................................................................................................... 12 Displays ................................................................................................................................... 12 Control .................................................................................................................................... -

Chesapeake Bay Restoration Fund Projects Catalog 2012

CHESAPEAKE BAY RESTORATION FUND PROJECTS CATALOG 2012 CHESAPEAKE BAY RESTORATION FUND SUPPORTING ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION AND RESTORATION PROJECTS FOR THE CHESAPEAKE BAY PROJECTS CATALOG 2012 PROJECTS CATALOG 2012 Issue I The Division of Legislative Services of the Virginia General Assembly publishes this catalogue. The information contained in these pages is current as of May 2012. Thank you to all of our partners and to all grantees of the Foundation who have provided text and materials for this catalogue. This catalogue was developed for all agencies, organizations, and individuals interested in environmental education and restoration projects on the bay and its rivers. General Assembly Division of Legislative Services Compiled and Edited by Theresa Schmid Research Associate iv TABLE OF CONTENTS I. CHESAPEAKE BAY RESTORATION FUND HISTORY II. CHESAPEAKE BAY ADVISORY COMMITTEE III. SUMMARY OF CBRF ACTIVITIES IV. APPLYING FOR A GRANT A. CRITERIA B. APPLICATION PROCEDURES GRANT ACTIVITIES FROM 2000-2012 V. GRANT PROJECTS LIST A. 2000 INDEX B. 2001 INDEX C. 2002 INDEX D. 2003 INDEX E. 2004 INDEX F. 2005 INDEX G. 2006 INDEX H. 2007 INDEX I. 2008 INDEX J. 2009 INDEX K. 2010 INDEX L. 2011 INDEX M. 2012 INDEX VI. ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION PROJECTS A. SCHOOLS B. ORGANIZATIONS - EDUCATIONAL FOR: 1. YOUTH 2. COMMUNITY v VII. RESTORATION/CONSERVATION PROJECTS A. MONITORING B. EASEMENTS VIII. FINANCIAL SUMMARIES IX. INDEX vi I. HISTORY In 1992, the Virginia General Assembly enacted legislation, co-patroned by Senator Frederick Quayle and Delegate Harvey Morgan, which established the Chesapeake Bay preservation license plate. The design included drawings of bay grass, oysters and crabs, and read “Friends of the Chesapeake." The Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) began issuing the specialty plates in December 1992. -

Owner's Manual

OWNER’S MANUAL FUEL SYSTEMS CALIFORNIA AIR RESOURCES BOARD (CARB) Boats manufactured for use in California for model year 2018 Outboard, sterndrive and inboard powered boats sold in the and after meet the California EVAP Emissions regulation for state of California are equipped with special components and spark-ignition marine watercraft. Boats meeting this certified to meet stricter environmental standards and exhaust requirement will have the following label affixed near the helm. emissions. All boats sold in California since 2009 are required to meet Super-Ultra-Low (four-star) emissions. EXHAUST EMISSIONS Operating, servicing and maintaining a Sterndrive and inboard marine engine recreational marine vessel can expose you to powered boats meeting CARB’s exhaust chemicals including engine exhaust, carbon emission standards are required to display the four-star label on the outside of the hull monoxide, phthalates and lead, which are known above the waterline. Outboard and to the State of California to cause cancer and personal watercraft marine engines may birth defects or other reproductive harm. To also comply with these standards. minimize exposure, avoid breathing exhaust, service your vessel in a well-ventilated area and wear gloves or wash your hands frequently when servicing this vessel. For more information go to: Carbon monoxide (CO) can cause brain damage or death. www.P65warnings.ca.gov/marine Engine and generator exhaust contains odorless and colorless carbon monoxide gas. Carbon monoxide will be around the back of the boat when engines or generators The fuel system in boats marketed in states other than California are running. Signs of carbon monoxide poisoning include complies with U.S. -

Operation Guide

OPERATION GUIDE HYDROVANE llllllll HYDROVANE INTERNATIONAL MARINE 2424 HAYWOOD AVE WEST VANCOUVER | BC CANADA | V7V 1Y1 STEERING THE DREAM www.hydrovane.com OPERATION & TROUBLESHOOTING GUIDE OCTOBER 2017 We are always pleased to receive photos and performance reports! If you are having any type of problem, please read this guide carefully and do not hesitate to contact us so we can work through it with you. CONTENTS A. OPERATION OVERVIEW .................................................................................................... 2 Sailing – Hydrovane in Use ................................................................................................................................. 2 Sailing – Hydrovane Not In Use ......................................................................................................................... 2 Motoring – Hydrovane Not In Use .................................................................................................................... 3 Motoring – Hydrovane In Use with Tiller Pilot ................................................................................................ 3 Hydrovane Rudder and Maneuverability ........................................................................................................ 4 B. VARIABLE CONTROLS – RATIO AND VANE AXIS .............................................................. 5 Ratio Control (Steerage) ..................................................................................................................................... -

The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Linfield Alumni Book Gallery Linfield Alumni Collections 2019 Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris John Kerr Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerr, John, "Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris" (2019). Linfield Alumni Book Gallery. 1. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books/1 This Book is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Book must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers Before the Mast, The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris By John Kerr Carol Lew Simons, Contributing Editor Cover photo by Shep Root Third Edition This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/. 1 PREFACE AND A TRIBUTE TO REGINA Steven Katona Somehow wood, steel, cable, rope, and scores of other inanimate materials and parts create a living thing when they are fastened together to make a ship. I have often wondered why ships have souls but cars, trucks, and skyscrapers don’t. -

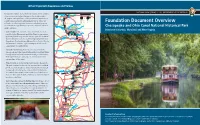

Foundation Document Overview W a R R I O R M O U N Referred to As Other Important Resources and Values.Program 28 170 T a I N

Other Important Resources and Values NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Canal Place State Heritage Area No 68 ek rth Canal Terminus Cre Bran Feeder Dam 8 ills 0 1 5 10 Kilometers Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park contains ch Po W t Guard Lock 8 A I N omac R M O U N T iver CUMBERLAND W I L L S 0 1 5 10 Miles ALT Cumberland Visitor Center 220 28 43C North 28 other resources and values that may not be fundamental to Evitts Creek Aqueduct Canal and Other trail North Branch 180 towpath trail Evitts Creek Canal mileage Rapids and E V I T 20 Locks 73–75 T S M O U N T A I N marker hazardous area the purpose and significance of the park, but are important to Lockhouse 75 Irons Mountain Patterson Wheelchair-accessible Boat launch Creek Lock 72 68 Spring Gap Spring Gap Restrooms Drive-in camping area consider in management and planning decisions. These are Picnic area Hiker-biker campsite 51 Emergency telephone Foundation Document Overview W A R R I O R M O U N referred to as other important resources and values.program 28 170 T A I N Pigmans Ferry Creek Oldtown-Battie Mixon Lock 71 n South w Bra Oldtown o M O U N T A I N nch Locks 69–70 T P O L I S H offer visitors the opportunity to experience different eras of the P k oto ee mac Ri Cr ve r Potomac Forks Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park GREEN RIDGE Lock 68 ile STATE FOREST enm canal’s existence.