Raphaël Zarka FORBID- DEN CON- JUNCTION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource Guide 4

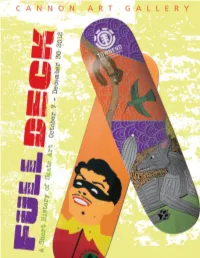

WILLIAM D. CANNON AR T G A L L E R Y TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 5 The Artful Thinking Program 7 Curriculum Connections 8 About the Exhibition 10 About Street Skateboarding 11 Artist Bios 13 Pre-visit activities 33 Lesson One: Emphasizing Color 34 Post-visit activities 38 Lesson Two: Get Bold with Design 39 Lesson Three: Use Text 41 Classroom Extensions 43 Glossary 44 Appendix 53 2 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-Visit section of the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-Visit Activities to reinforce learning. The guide and exhibit images were adapted from the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art Exhibition Guide organized by: Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, California. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing works first and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

Skate Parks: a Guide for Landscape Architects and Planners

SKATE PARKS: A GUIDE FOR LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS by DESMOND POIRIER B.F.A., Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Rhode Island, 1999. A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE Department of Landscape Architecture College of Regional and Community Planning KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2008 Approved by: Major Professor Stephanie A. Rolley, FASLA, AICP Copyright DESMOND POIRIER 2008 Abstract Much like designing golf courses, designing and building skateboard parks requires very specific knowledge. This knowledge is difficult to obtain without firsthand experience of the sport in question. An understanding of how design details such as alignment, layout, surface, proportion, and radii of the curved surfaces impact the skateboarder’s experience is essential and, without it, a poor park will result. Skateboarding is the fastest growing sport in the US, and new skate parks are being fin- ished at a rate of about three per day. Cities and even small towns all across North America are committing themselves to embracing this sport and giving both younger and older participants a positive environment in which to enjoy it. In the interest of both the skateboarders who use them and the people that pay to have them built, it is imperative that these skate parks are built cor- rectly. Landscape architects will increasingly be called upon to help build these public parks in conjunction with skate park design/builders. At present, the relationship between landscape architects and skate park design/builders is often strained due to the gaps in knowledge between the two professions. -

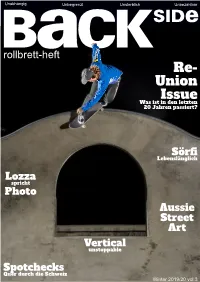

Side Rollbrett-Hefta Re- Union

Unabhängig Unbegrenzt Unsterblich Unbezahlbar B CKSIDe rollbrett-hefta Re- Union Was istIssue in den letzten 20 Jahren passiert? Sörfi Lebenslänglich Lozza spricht Photo Aussie Street Art Vertical unstoppable Spotchecks Quer durch die Schweiz Winter 2019/20 vol.3 -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Forword We are Wer hätte das gedacht? Von einem Jahr noch unvorstellbar. Was ist passiert? Mitte der 90ier Jahren veranlasste mich ein derber gezogen sind und obwohl alle ziemlich verschieden Trennungsschmerz (die Geschichte ist Netflix das Rollbrett uns alle vereint hat. Sei das in St. serientauglich) meinen Wut, meine Energie und Gallen am Vadian, in Zürich auf der Landiewiese freie Zeit in ein Projekt zu investieren. Backside oder EMB in San Francisco. rollbrett-heft wurde geboren und als Nicole ‘Nikita’ Hecht mein erstes zusammengeklebtes Layout aus Von Rebellen kann heute wohl nicht mehr meinen Händen riss, wurde es richtig spannend. sprechen wenn ein Luxus Modelabel wie Armani mit Skateboarding wirbt, Tony Hawk im Jahr Millionen Zwei Ausgaben später verabschiedete ich mich verdient, SB-Foto/Videograph einen Oscar gewinnt, 1996 ins Ausland was auch das definitive ‘Aus’ür f ehemalige Skatepros in Spielfilmen zu sehen sind, Backside bedeutete. Nach der Rückkehr hatte ich erfolgreiche Modemarken aufbauen oder New den Appetit nach über 10 Jahren Skateboarding Balance ein Rider Team stellt (New Balance! verloren und bin sowieso gleich wieder in das Wirklich?). Was noch fehlt ist das Skateboarding als nächste Auslandabenteuer gestürzt. olympische Disziplin aufgenommen wird. 23 Jahre später melden wir uns zurück. Doch es gibt auch eine Backside, die wir mit unserem Unerwartet. In Farbe.Was ist den jetzt los? Schon ultimativen Re-Union Issue aufgreifen wollen. -

Reversing the Isolation and Inadequacies of Skateparks: Designing To

REVERSING THE ISOLATION AND INADEQUACIES OF SKATEPARKS: DESIGNING TO SUCCESSFULLY INTEGRATE SKATEBOARDING INTO DOWNTOWN LURAY, VIRGINIA by DANIEL BENJAMIN PENDER (Under the Direction of Bruce K. Ferguson) ABSTRACT Skateboarding has become the fastest rising social sport in America. Historically, this sport tends to attract a stereotyped grungy, nomadic, “pack-oriented” crowd that thrives off of the buzz of performing tricks in urban spaces. Unfortunately, this self- expressive crowd, as well as the destructive nature of the sport, has caused much of the general public to form negative opinions of skateboarding. Because of this, in combination with recent trends to “green up” cities and to accommodate for the sport’s increasing popularity, skateboarding (both physically and socially) is being forced to the outskirts of communities where poorly-built, less accessible, and environmentally insensitive skateparks are taking the place of socially rich urban skating environments. This thesis investigates the social/environmental issues associated with isolated and inadequate skateparks and the implications they may have on the future of the sport. Insight gained is applied to a skatepark design for my hometown of Luray, Virginia. INDEX WORDS: skateparks, skate plaza, skateable art, concrete obstacles, prefab obstacles, Luray, Virginia REVERSING THE ISOLATION AND INADEQUACIES OF SKATEPARKS: DESIGNING TO SUCCESSFULLY INTEGRATE SKATEBOARDING INTO DOWNTOWN LURAY, VIRGINIA by DANIEL BENJAMIN PENDER B.S., North Carolina State University, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Daniel Benjamin Pender All Rights Reserved REVERSING THE ISOLATION AND INADEQUACIES OF SKATEPARKS: DESIGNING TO SUCCESSFULLY INTEGRATE SKATEBOARDING INTO DOWNTOWN LURAY, VIRGINIA by DANIEL BENJAMIN PENDER Major Professor: Bruce K. -

Hablas Skatepark?

32 s s 33 PLANTEAR UN © Constructo SKATE PARK, UN ASUNTO PARA EXPERTOS +¿QUE MATERIALES?¿PARA CUANTO TIEMPO? +ELEGIR UN BUEN DIRECTOR DE OBRA. +¿H ABLAS SKATEPARK? +¿ DONDE IMPLANTAR UN SKATEPARK?. +“SK ATE PARK” INCLUYE “PARQUE”. +E JEMPLOS PARA TODOS LOS PRESUPUESTOS. +EL MUSEO DE LOS “ERRORES”. REAL FEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA +PO RTFOLIO DE PATINAJE 1 REAL FEDERACIÓN ESPAÑOLA DE PATINAJE PLANTEAR UN SKATEPARK, UN ASUNTO PARA EXPERTOS 2 ANALISIS COMPARATIVO ENTRE SKATEPARKS skatepark skatepark ¿QUÉ MATERIALES? modular integrado ¿PARA CÚANTO TIEMPO? Presupuesto / depreciación de la inversión – ++ Instalación de las instalaciones + + ¿COMO DEBE SER UN SKATEPARK? PODEMOS RESOLVER ESTA Flexibilidad a restricciones / adaptabilidad – – ++ PREGUNTA A TRAVES DE LA DISTINCION ENTRE DOS ENFOQUES DE CONSTRUCCION: MODULARES O INTEGRADOS Durabilidad – – ++ Entretenimiento – – ++ 1. Parques de skate "modulares" 1. Parques de skate "integrados" Compuestos de varios módulos prefabricados de madera, metal El skatepark de hormigón ha sido durante 40 años la única referencia Resistencia al mal tiempo – – u hormigón colocados en una solera de hormigón (o lo que es peor válida para skateparks al aire libre, coincidiendo con la evolución del ++ en caso de caídas, de asfalto) previamente moldeada para la ocasión. skateboarding moderno, Pero también cubre las expectativas al mismo El skatepark modular puede funcionar si se adapta a circunstancias tiempo a los patinadores y espectadores siempre que sean entendidos muy específicas: Si es indoor o cubierto, debe ser realizado por como verdaderos proyectos arquitectónicos ya que oferta infinitas Relevancia / adecuación deportiva a las expectativas de los usuarios empresas con verdadera experiencia en la construcción de skateparks posibilidades de integración paisajística. – – ++ de madera que sean capaces de resolver los problemas de "rebote" y Mucho más presentes, por el momento, en otros lugares de Europa rodada en transiciones de madera. -

Descriptive Opinion “Boja Have Skate” Community in Boja

DESCRIPTIVE OPINION “BOJA HAVE SKATE” COMMUNITY IN BOJA A THESIS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Thesis Project on AmericanCultural Studies in English Department Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by : Octy Ayu Kinasih NIM : A2B009092 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2016 PRONOUNCEMENT The writer states thruthfully that this thesis is compiled by herself without taking any results from other researchers in S-1, S-2, S-3, and in diploma degree of any universities. In addition, the writer ascertains that she does not take the material from other thesis or someone’s work except for the references mentioned. Semarang, July 2016 Octy Ayu Kinasih ii APPROVAL Approved by, Thesis Advisor 25 July 2016 Prof. Dr. Nurdien Harry Kistanto, MA NIP. 19521103 198012 1 001 iii VALIDATION iv MOTTO AND DEDICATION Ability is what you're capable of doing. Motivation determines what you do. Attitude determines how well you do it. -Lou Holtz- This paper is dedicated to My beloved Dad and Groom to be For your birthday gift v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Alhamdulillah. Praise to God Almighty, who has given strength and blessing for the writer so this thesis on “Relationship of Mass Media towards Developments of Skateboard as Reflected as American Popular Culture in Boja”came to a completion. On this occasion, the writer would like to thank all those people who have contributed to the completion of this thesis. The deepest appreciation and gratitude are extended Prof. Dr. Nurdien Harry Kistanto, MA — as the writer’s advisor— who has given his continuous guidance, helpful corrections, moral support, advice, suggestions, and nice discussions about everything. -

Dwaya Rhenega 08206244017.Pdf

PEMANFAATAN TOKOH LEGENDARIS BARAT SEBAGAI ILUSTRASI DALAM PERANCANGAN DESAIN PAPAN SKATE DISEASE SKATEBOARD TUGAS AKHIR KARYA SENI Diajukan kepada Fakultas Bahasa dan Seni Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta untuk Memenuhi sebagian Persyaratan guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Disusun Oleh: Dwaya Rhenega NIM 08206244017 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SENI RUPA FAKULTAS BAHASA DAN SENI UNIVERSITAS NEGERI YOGYAKARTA 2014 Motto “Menjadi hidup dengan ilmu, yang telah mengajar lagi yang memberi kepastian menurut satu pilihan masing-masing” (MSR) v PERSEMBAHAN Tugas Akhir Karya Seni ini ku persembahkan untuk.. Kedua orang tua yang telah memberikan segalanya Serta kakakku atas semua dukungannya vi DAFTAR GAMBAR Halaman Gambar 1 Tabel Psikologis Warna................................................. 14 Gambar 2 Contoh Huruf Oldstyle................................................... 15 Gambar 3 Contoh Huruf Transitional............................................ 15 Gambar 4 Contoh Huruf Modern................................................... 16 Gambar 5 Contoh Huruf Sans Serif................................................ 17 Gambar 6 Contoh Huruf Slab Serif................................................ 17 Gambar 7 Contoh Huruf Script....................................................... 18 Gambar 8 Contoh Huruf Decorative............................................... 18 Gambar 9 Drowning Girl ( Roy Lichtenstein )............................... 25 Gambar 10 Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? ( Richard Hamilton -

Langages, Espaces, Temps, Societes » La Transmission

UNIVERSITE DE FRANCHE-COMTE ECOLE DOCTORALE « LANGAGES, ESPACES, TEMPS, SOCIETES » Thèse en vue de l’obtention du titre de docteur en SOCIOLOGIE LA TRANSMISSION DES SAVOIRS DU SKATEBOARD A L’EPREUVE DES NOUVELLES TECHNOLOGIES DE L’INFORMATION ET DE LA COMMUNICATION (Volume 1) Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Sébastien CRETIN Le 25 Octobre 2007 Sous la co-direction de Mme la Professeur Dominique JACQUES-JOUVENOT Et M Gilles VIEILLE-MARCHISET Maître de Conférence Universitaire- Habilité à diriger des recherches Membres du jury : Christophe GIBOUT, Maître de conférences à l’université du Littoral-Côte d'Opale Dominique JACQUES-JOUVENOT, Professeur à l’université de Franche-Comté Pascal LARDELLIER, Professeur à l’université de Bourgogne Gilles VIEILLE-MARCHISET, Maître de Conférences à l’université de Franche-Comté - Habilité à diriger des recherches LA TRANSMISSION DES SAVOIRS DU SKATEBOARD A L’EPREUVE DES NOUVELLES TECHNOLOGIES DE L’INFORMATION ET DE LA COMMUNICATION - Page 2 sur 515 - LA TRANSMISSION DES SAVOIRS DU SKATEBOARD A L’EPREUVE DES NOUVELLES TECHNOLOGIES DE L’INFORMATION ET DE LA COMMUNICATION Remerciements Je tiens sincèrement à remercier l’ensemble des personnes qui ont été à mes côtés durant la réalisation de cette thèse. D’une part, à Dominique Jacques-Jouvenot et à Gilles Vieille-Marchiset qui ont accepté d’assumer la direction de mes recherches depuis mon DEA, et qui m’ont guidé par leurs regards avisés de sociologues. Je leur suis très reconnaissant de m’avoir fait part de leurs connaissances et d’avoir su orienter mes lectures et mes recherches. Leurs conseils, ainsi que leurs critiques, m’ont accompagné jusqu'à l’achèvement de ma thèse. -

Le Skateboard, Industrie Et Culture Audiovisuelle

Faculté des Lettres et Civilisations Département des Sciences de l'Information et de la Communication Master 2 Audiovisuel, Médias numériques interactifs, Jeux Année universitaire 2018-2019 Le skateboard, industrie et culture audiovisuelle Adrien Motte Tuteur universitaire : Catherine Dessinges Remerciements Merci à tous mes camarades de Lyon 3 avec qui j’ai passé trois belles années : Gabriel, Lou, Jean-Loup, Léna, Léa, Orane, Maëlle, Joanna, Aurélien, Sanam, Élisa et tous les autres... Merci à Mme Dessinges pour ses précieux conseils et sa bienveillance. Merci au système éducatif public français, longue vie à lui. Merci à Fred Demard qui a répondu à mes questions pendant ses vacances. Merci à Julien Laurent pour avoir pris le temps de répondre à mes questions. Merci aux communautés du freeware et de Wikipedia. Merci à tous ceux qui ont répondu à mon questionnaire. Merci à tous ceux avec qui j’ai discuté de mon sujet, ça m’a beaucoup aidé à prendre du recul sur mes propos : Aurélien Volo, Grégoire Mathieu, Bertrand Oswald, Antoine Prost-Verdure, Pierre Boccon-Jibod, Anthony Tozlanian, Fred Mortagne (même s’il ne s’en souvient probablement pas)… Merci au Thrasher Magazine de toujours être “True to this”. Merci à Jake Phelps et P-Stone, reposez en paix. Merci à Nietzsche, vive l’élévation. Merci à mes parents pour le financement de mes études et pour leur soutien inconditionnel. 1 Introduction Au cinéma ou dans les séries, lorsque qu’un scénariste veut écrire un personnage adolescent, blanc, un peu rebel, il y a de fortes chances qu’on nous montre à un moment donné des posters de skateurs dans sa chambre ou qu’il pratique lui-même le skateboard dans une scène. -

ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY of LIFE SCIENCES Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences

● ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES Institute of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Luís Carlos Borges Rodrigues SKATEABLE SPACES: FOUND SPACE AND THE PURPOSELY BUILT SKATE SPACE IN PORTUGAL - PERCEPTION, TRENDS, OPPORTUNITIES AND MISTAKES RULARUUM: LEITUD RUUM JA TEADLIKULT LOODUD RULAMAASTIKUD PORTUGALIS – ETTEKUJUTUS, TRENDID, VÕIMALUSED JA VEAD Master’s thesis in Landscape Architecture Supervisor: Professor Simon Bell, Phd Tartu 2020 Dedications to Ruben probably my first skate buddy who left us way too soon! rest in peace to Jorge Rodrigues who despite not understanding skateboarding took me to a skate shop in 2004 located 430km away from my everyday skate spots where I got my first decent skateboard, and who was also the first to recommend me to enrol in Landscape Architecture studies. to Alexandre Cunha who indirectly introduced me to skateboarding by inviting me to play THPS in the early 2000s! to André Lage the jack of all trades who has tried all the extreme sports and my most loyal companion in street skate sessions to Simon Bell and Friedrich Kuhlmann for the opportunity I was given in 2016 to fulfill the old dream of studying Landscape Architecture abroad to Tony Hawk I would not be writing this thesis if it weren’t for the THPS saga. The concept for this work (skateable landscapes) largely comes from the high degree of skateability (far exceeding reality) allowed in the game’s virtual environments (although often based in real locations) THPS was my gateway to skateboarding world and for that, as for the rest you have been doing for skateboarding and skateboarders, thank you. -

Skate, Illustration and the Other Side of the Skateboard

4.8. Deka – skate, illustration and the other side of the skateboard Jorge Brandão Pereira 1 Diogo Valente 2 Diogo Soares 2 Paula Tavares 2 Abstract Skate and skatebording culture emerge from the street space, which simultaneously influences artists, designers, illustrators, musicians, writers, filmmakers and creatives. The Deka project focuses on this relationship between the urban culture of skateboarding and illustration and the expressions that this relationship trigger. To this research, various activities were structured throughout 2013, such as artistic events, a graphic diary and the participation on the ‘Milhões de Festa’ festival, with the outreach event ‘Dekalhões’, where was spurred an environment that combined art, illustration, music and local skaters, wrapped in a diverse audience. The action plan was structured in order to promote new artists and the skate culture in Northern Portugal, through research and analysis of intervention opportunities at public events, physical spaces and digital universes. It is sustained that this urban counter-culture is an opportunity to enhance and Express creativity and the case study of the research reinforces its potential to become a starting point for artistic intervention. dekaday.tumblr.com Keywords: illustration, skate, urban culture Background and context The practical-based project happens with the aim of combining and bringinf to Skateboarding other parallel perspectives. Having Skateboarding as a starting point, from it emerge associated various hypotheses or ideas to explore: (i) skate as inspiration for artistic creation, (ii) in the dissemination and support to the activity and (iii) as an agent of integration of all the surrounding culture in a new context. Allied to Graffiti and Music, Skate emerges from the street space, influencing artists, designers, illustrators, musicians, writers, directors, designers and other creatives. -

Filhos Do Betão 30 Anos De Skate Em Portugal; Skate, Identidade E Subculturas Juvenis Em Espaço Urbano”

Departamento de Antropologia “Filhos do Betão 30 Anos de skate em Portugal; Skate, identidade e subculturas juvenis em espaço urbano” Nuno Miguel Pereira Menezes Tese submetida como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Antropologia – Imagem e Comunicação Orientadora: Professora Doutora Graça Índias Cordeiro, Professora Auxiliar com agregação no ISCTE – IUL Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Setembro 2010 I OS FILHOS DO BETÃO II OS FILHOS DO BETÃO Departamento de Antropologia “Filhos do Betão 30 Anos de skate em Portugal; Skate, identidade e subculturas juvenis em espaço urbano” Nuno Miguel Pereira Menezes Tese submetida como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Antropologia – Imagem e Comunicação Orientadora: Professora Doutora Graça Índias Cordeiro, Professora Auxiliar com agregação no ISCTE – IUL Instituto Universitário de Lisboa III OS FILHOS DO BETÃO Agradecimentos Em primeiro lugar, quero agradecer à minha amiga e companheira Maria Rita Alves dos Santos da Costa e Silva, que muito me ajudou e sempre me acompanhou desde o início desta dissertação dando-me sempre o alento necessário, não só nos momentos mais enfermos do meu estado de espírito mas também nos momentos em que a minha fé e confiança neste trabalho se encontrava abalada, reavivando assim as minhas forças, motivando-me a continuar, e colocando-me em sentido contra as adversidades com que me fui deparando. Obrigado Marita, sem ti este trabalho nem teria começado. Quero agradecer também ao meu grande amigo Vasco Neves por me ter cedido uma série de informação e de me ter disponibilizado o seu tempo, para além de me ter direccionado aos locais certos e apresentado às pessoas correctas.