A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index Locorum

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02817-3 - Libertas and the Practice of Politics in the Late Roman Republic Valentina Arena Index More information Index locorum Appian Caesar Bella Civilia Bellum Civile 1.10, 151, 152 1.5, 201 1.11, 150–1 Bellum Gallicum 1.12, 125, 137 6.22, 144, 145 2.23, 189 Cassiodorus Grammaticus 2.27, 172 7.150.10ff. (GRF Varro 268), 269–70 Archytas Cato, Marcus Porcius fr. 3.6–11 Huffman, 102 fr. 252 (ORF 8,p.96), 67, 142 Pseudo-Archytas fr. 33.14 Huffman, fr. 80 Peter, 85 108 Charisius Aristotle Ars Grammatica Ethica Nicomachea 62.14ff., 267 1130b30, 103 Cicero 1131a-b, 104 Brutus 1131a-b., 103–4 164, 131 Politica De amicitia 1265b26–9, 83 41, 60 1270b21–2, 83 De domo sua 1280a 25–31, 105 19, 188 1294a36–b18, 105 19–20, 188–9 1301a26–b4, 104, 121–2 20, 185 1301b29–1302a8, 104–5 100, 213 1317b2–10, 122 102, 213 1318b25–6, 105 111, 213 Asconius 113, 214 8C, 61–2, 173 114, 213 57C, 177–8 De finibus 71.17C, 128 1.6, 253 78C, 138, 139 3.62–3, 262 Athenaenus 3.67, 156 4.141a–c, 83–4 4.79, 86 Augustine De inventione rhetorica [Ars Breviata] 1.8, 254 3.25, 274–5 2.53, 135 De civitate Dei De lege agraria 2.21, 250 1.17, 232 Aulus Gellius 1.21–2, 240 Noctes Atticae 2.5, 61 1.9.12, 164 2.7, 231 10.20.2, 64 2.9, 231 312 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02817-3 - Libertas and the Practice of Politics in the Late Roman Republic Valentina Arena Index More information Index locorum 313 2.10, 231 3.55, 157 2.11–14, 231 3.57, 161 2.15, 231–2 3.61–62, 161 2.16–17, -

J. Zabłocki LE MAGISTRATURE ROMANE * 1. L'epoca Regia Stando Alla Tradizione, Dopo Aver Ucciso Il Gemello Remo Romolo Divenne

J. Zabłocki ”ÌË‚ÂрÒËÚÂÚ ´ ‡р‰Ë̇· –ÚÂه̇ ¬˚¯ËÌÒÍÓ„Óª ¬‡р¯‡‚˚, œÓθ¯‡ LE MAGISTRATURE ROMANE * 1. L’epoca regia costoro ogni cinque giorni si tirava a sorte un interrex finché gli auspici non consentissero di Stando alla tradizione, dopo aver ucciso il procedere all’elezione del re. Scelto il can- gemello Remo Romolo divenne capo (rex) didato (captio), lo si sottoponeva all’approva- della civitas che lui stesso aveva fondato. zione divina, confermata dal rinnovo degli Dapprima il potere regio fu probabilmente auspici, e, in senato, all’auctoritas patrum. poco esteso. I primi re lo esercitavano su una Quindi, con una lex curiata de imperio, piccola comunità di liberi abitanti di un l’assemblea del popolo (comitia curiata) lo territorio molto ristretto. Le decisioni erano investiva del potere supremo (imperium). Al prese e attuate da tutti: il re le proponeva, il nuovo re non restava che prendere il governo popolo le approvava o respingeva. Le decisioni (inauguratio). più importanti riguardavano la guerra, la pace e L’elezione del re e, più in generale, altri problemi di interesse collettivo. Il re l’interregno risaltavano le prerogative dei convocava le assemblee popolari (comitia patres, chiamati al governo e a sondare il curiata), il consiglio degli anziani (senatus) e il volere divino. Né altri avrebbero potuto farlo: comando dell’esercito (imperium), ricercava i il potere di prendere gli auspici era sacro e, segni della volontà divina nel volo degli uccelli quindi, riservato ai patres: in età repubblicana (auspicia), officiava il culto. Inoltre risolveva sarebbe stato un’esclusiva delle magistrature le controversie (iurisdictio) e dava esecuzione patrizie. -

2. Fighting Corruption: Political Thought and Practice in the Late Roman Republic

2. Fighting Corruption: Political Thought and Practice in the Late Roman Republic Valentina Arena, University College London Introduction According to ancient Roman authors, the Roman Republic fell because of its moral corruption.i Corruption, corruptio in Latin, indicated in its most general connotation the damage and consequent disruption of shared values and practices, which, amongst other facets, could take the form of crimes, such as ambitus (bribery), peculatus (theft of public funds) and res repentundae (maladministration of provinces). To counteract such a state of affairs, the Romans of the late Republic enacted three main categories of anticorruption measures: first, they attempted to reform the censorship instituted in the fifth century as the supervisory body of public morality (cura morum); secondly, they enacted a number of preventive as well as punitive measures;ii and thirdly, they debated and, at times, implemented reforms concerning the senate, the jury courts and the popular assemblies, the proper functioning of which they thought might arrest and reverse the process of corruption and the moral and political decline of their commonwealth. Modern studies concerned with Roman anticorruption measures have traditionally focused either on a specific set of laws, such as the leges de ambitu, or on the moralistic discourse in which they are embedded. Even studies that adopt a holistic approach to this subject are premised on a distinction between the actual measures the Romans put in place to address the problem of corruption and the moral discourse in which they are embedded.iii What these works tend to share is a suspicious attitude towards Roman moralistic discourse on corruption which, they posit, obfuscates the issue at stake and has acted as a hindrance to the eradication of this phenomenon.iv Roman analysis of its moral decline was not only the song of the traditional laudator temporis acti, but rather, I claim, included, alongside traditional literary topoi, also themes of central preoccupation to Classical political thought. -

Emperors and Generals in the Fourth Century Doug Lee Roman

Emperors and Generals in the Fourth Century Doug Lee Roman emperors had always been conscious of the political power of the military establishment. In his well-known assessment of the secrets of Augustus’ success, Tacitus observed that he had “won over the soldiers with gifts”,1 while Septimius Severus is famously reported to have advised his sons to “be harmonious, enrich the soldiers, and despise the rest”.2 Since both men had gained power after fiercely contested periods of civil war, it is hardly surprising that they were mindful of the importance of conciliating this particular constituency. Emperors’ awareness of this can only have been intensified by the prolonged and repeated incidence of civil war during the mid third century, as well as by emperors themselves increasingly coming from military backgrounds during this period. At the same time, the sheer frequency with which armies were able to make and unmake emperors in the mid third century must have served to reinforce soldiers’ sense of their potential to influence the empire’s affairs and extract concessions from emperors. The stage was thus set for a fourth century in which the stakes were high in relations between emperors and the military, with a distinct risk that, if those relations were not handled judiciously, the empire might fragment, as it almost did in the 260s and 270s. 1 Tac. Ann. 1.2. 2 Cass. Dio 76.15.2. Just as emperors of earlier centuries had taken care to conciliate the rank and file by various means,3 so too fourth-century emperors deployed a range of measures designed to win and retain the loyalties of the soldiery. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

Exemplarity in Roman Culture: the Cases of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia Author(S): Matthew B

Exemplarity in Roman Culture: The Cases of Horatius Cocles and Cloelia Author(s): Matthew B. Roller Source: Classical Philology, Vol. 99, No. 1 (January 2004), pp. 1-56 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/423674 . Accessed: 08/04/2011 17:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Classical Philology. http://www.jstor.org EXEMPLARITY IN ROMAN CULTURE: THE CASES OF HORATIUS COCLES AND CLOELIA matthew b. -

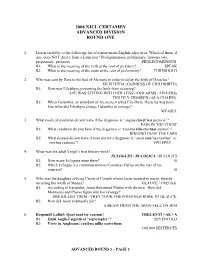

2008 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2008 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Listen carefully to the following list of synonymous English adjectives. Which of them, if any, does NOT derive from a Latin root? Prolegomenous, preliminary, introductory, preparatory, prefatory PROLEGOMENOUS B1: What is the meaning of the verb at the root of prefatory? SPEAK B2: What is the meaning of the noun at the root of preliminary? THRESHOLD 2. Who was sent by Hera to the bed of Alcmene in order to delay the birth of Heracles? EILEITHYIA (GODDESS OF CHILDBIRTH) B1: How was Eileithyia preventing the birth from occuring? SHE WAS SITTING WITH HER LEGS (AND ARMS / FINGERS) TIGHTLY CROSSED (AS A CHARM). B2: When Galanthis, an attendant of Alcmene, tricked Eileithyia, Heracles was born. Into what did Eileithyia change Galanthis in revenge? WEASEL 3. What medical condition do you have if the diagnosis is “angina (ăn-jī΄nƏ) pectoris”? PAIN IN THE CHEST B1: What condition do you have if the diagnosis is “tinnitus (tĭn-eye-tus) aurium”? RINGING IN/OF THE EARS B2: What disease do you have if your doctor’s diagnosis is “sacer (săs΄Ər) morbus” or “morbus caducus”? EPILEPSY 4. What was the adult Vergil’s first literary work? ECLOGUES / BUCOLICA / BUCOLICS B1: How many Eclogues were there? 10 B2: Which Eclogue is a commiseration to Cornelius Gallus on the loss of his mistress? 10 5. Who was the daughter of King Creon of Corinth whom Jason wanted to marry, thereby incurring the wrath of Medea? GLAUCE / CREUSA B1: According to Euripides, Jason threatened Medea with divorce. How did Mermerus and Pheres figure into her revenge? SHE KILLED THEM / THEY TOOK THE POISONED ROBE TO GLAUCE. -

75 AD NUMA POMPILIUS Legendary, 8Th-7Th Century B.C. Plutarch Translated by John Dryden

75 AD NUMA POMPILIUS Legendary, 8th-7th Century B.C. Plutarch translated by John Dryden Plutarch (46-120) - Greek biographer, historian, and philosopher, sometimes known as the encyclopaedist of antiquity. He is most renowned for his series of character studies, arranged mostly in pairs, known as “Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans” or “Parallel Lives.” Numa Pompilius (75 AD) - A study of the life of Numa Pompilius, an early Roman king. NUMA POMPILIUS THOUGH the pedigrees of noble families of Rome go back in exact form as far as Numa Pompilius, yet there is great diversity amongst historians concerning the time in which he reigned; a certain writer called Clodius, in a book of his entitled Strictures on Chronology, avers that the ancient registers of Rome were lost when the city was sacked by the Gauls, and that those which are now extant were counterfeited, to flatter and serve the humour of some men who wished to have themselves derived from some ancient and noble lineage, though in reality with no claim to it. And though it be commonly reported that Numa was a scholar and a familiar acquaintance of Pythagoras, yet it is again contradicted by others, who affirm that he was acquainted with neither the Greek language nor learning, and that he was a person of that natural talent and ability as of himself to attain to virtue, or else that he found some barbarian instructor superior to Pythagoras. Some affirm, also, that Pythagoras was not contemporary with Numa, but lived at least five generations after him; and that some other Pythagoras, a native of Sparta, who, in the sixteenth Olympiad, in the third year of which Numa became king, won a prize at the Olympic race, might, in his travel through Italy, have gained acquaintance with Numa, and assisted him in the constitution of his kingdom; whence it comes that many Laconian laws and customs appear amongst the Roman institutions. -

GIPE-001655-Contents.Pdf

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Libnuy IIm~ mlll~ti 111Im11 ~llllm liD· . GIPE-PUNE-OO 16.5 5 ..~" ~W~"'JU.+fJuvo:.""~~~""VW; __uU'¥o~'W'WQVW.~~¥WM'tI;:J'-:~ BORN'S STANDARD LlBRtJLY. t~ ------------------------' t~ SCHLEGEL'S LECTURES ON MODERN HISTORY. t", IY LAMARTINE'S HISTORY OF THE FRENCH REVO~UTION· OF' 1841. fj " 50. JUIlIUS'S LETTERS, ..itb 1'01<', AJdibOUO, Eony.lDdex, &;C. B Volt. Co, 6&sg~l~~;~s~1~tfj;R~\¥I~Eg~H~.:~~8~\f!~~~:::tTI.~~e~: Comj.lJ.t;te u. , Vola., wiLia !nOel:, ' •. ~fJ; t TAYt..On·S (JEREMY) KOLY LIVING AND DYING. ,,,,,,,,01.1. f QOrrHE'S WORKS . .v"r In. [4·}'au9t." u."big'!niot.," "T0"'f'"lW TURn," ~ ~ ~titl. 'J }.;gJnont:') l'n,nsla:led by ~h88 ttWO\«WiC"" WH.• 14 Goetz von B,n .... ~ .aduncuu," tralHJated by iiI. WAin.x ~(u:'r. It. I $6,'68. 61. ee. 67, 75, & 112, NEANDER'S CHURCH HISTORY. Coretully ,''; l ."vt.cd by the Rzv. A • .I. W. MQl.lU*ON. & full. \HUl ladtx. 1::; CJ~ • NEANDER'S '-lfE OF CHRIST. to1 64, NEANDER'S PLANTING OF CHRISTIANITY, II< ANTIGNOSTlKUS, i i Volt. f.~ i CREG,ORY'$ (DR.) LETTERS ON THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION. «( • 153. JAMES' (G, P. R.) LOUIS XIV. Complet. in i Vola. 1'." .... ". t;-; ~ II< 70, SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS' UTERAflY WOlrKS, with Memoir, II Vol •• PorI. f(; ANDREW rULLER'S PRINCIPAL WORKS. 1'""".U. a; ,B~-:~~~S ANALOGY or RELIGION, AND SERMONS, wilh Nola. ~ t1 MISS BREMER'S WORKS. TransJated hy MAVY Rowrn. 'New Edition, ff'ri.e4. Eq ,\'1.11.1. 1" The ~eif4:rlboUfil" and other THlca.) Post 8yo. -

Histoire Romaine

HISTOIRE ROMAINE EUGÈNE TALBOT PARIS - 1875 AVANT-PROPOS PREMIÈRE PARTIE. — ROYAUTÉ CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. SECONDE PARTIE. — RÉPUBLIQUE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. - CHAPITRE IV. - CHAPITRE V. - CHAPITRE VI. - CHAPITRE VII. - CHAPITRE VIII. - CHAPITRE IX. - CHAPITRE X. - CHAPITRE XI. - CHAPITRE XII. - CHAPITRE XIII. - CHAPITRE XIV. - CHAPITRE XV. - CHAPITRE XVI. - CHAPITRE XVII. - CHAPITRE XVIII. - CHAPITRE XIX. - CHAPITRE XX. - CHAPITRE XXI. - CHAPITRE XXII. TROISIÈME PARTIE. — EMPIRE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. AVANT-PROPOS. LES découvertes récentes de l’ethnographie, de la philologie et de l’épigraphie, la multiplicité des explorations dans les diverses contrées du monde connu des anciens, la facilité des rapprochements entre les mœurs antiques et les habitudes actuelles des peuples qui ont joué un rôle dans le draine du passé, ont singulièrement modifié la physionomie de l’histoire. Aussi une révolution, analogue à celle que les recherches et les œuvres d’Augustin Thierry ont accomplie pour l’histoire de France, a-t-elle fait considérer sous un jour nouveau l’histoire de Rome et des peuples soumis à son empire. L’officiel et le convenu font place au réel, au vrai. Vico, Beaufort, Niebuhr, Savigny, Mommsen ont inauguré ou pratiqué un système que Michelet, Duruy, Quinet, Daubas, J.-J. Ampère et les historiens actuels de Rome ont rendu classique et populaire. Nous ne voulons pas dire qu’il ne faut pas recourir aux sources. On ne connaît l’histoire romaine que lorsqu’on a lu et étudié Salluste, César, Cicéron, Tite-Live, Florus, Justin, Velleius, Suétone, Tacite, Valère Maxime, Cornelius Nepos, Polybe, Plutarque, Denys d’Halicarnasse, Dion Cassius, Appien, Aurelius Victor, Eutrope, Hérodien, Ammien Marcellin, Julien ; et alors, quand on aborde, parmi les modernes, outre ceux que nous avons nommés, Machiavel, Bossuet, Saint- Évremond, Montesquieu, Herder, on comprend l’idée, que les Romains ont développée dans l’évolution que l’humanité a faite, en subissant leur influence et leur domination. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, C.319–50 BC

Ex senatu eiecti sunt: Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, c.319–50 BC Lee Christopher MOORE University College London (UCL) PhD, 2013 1 Declaration I, Lee Christopher MOORE, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Thesis abstract One of the major duties performed by the censors of the Roman Republic was that of the lectio senatus, the enrolment of the Senate. As part of this process they were able to expel from that body anyone whom they deemed unequal to the honour of continued membership. Those expelled were termed ‘praeteriti’. While various aspects of this important and at-times controversial process have attracted scholarly attention, a detailed survey has never been attempted. The work is divided into two major parts. Part I comprises four chapters relating to various aspects of the lectio. Chapter 1 sees a close analysis of the term ‘praeteritus’, shedding fresh light on senatorial demographics and turnover – primarily a demonstration of the correctness of the (minority) view that as early as the third century the quaestorship conveyed automatic membership of the Senate to those who held it. It was not a Sullan innovation. In Ch.2 we calculate that during the period under investigation, c.350 members were expelled. When factoring for life expectancy, this translates to a significant mean lifetime risk of expulsion: c.10%. Also, that mean risk was front-loaded, with praetorians and consulars significantly less likely to be expelled than subpraetorian members.