Hurst House and the Chesterfield Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outwood Academy Newbold, Derbyshire

Determination Case reference: REF3617 Referrer: A member of the public Admission authority: Outwood Grange Academies Trust for Outwood Academy Newbold, Derbyshire Date of decision: 12 September 2019 Determination I have considered the admission arrangements for September 2019 and September 2020 for Outwood Academy Newbold, Derbyshire in accordance with section 88I(5) of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998. I find that there are matters which do not conform with the requirements relating to admission arrangements in the ways set out in this determination. By virtue of section 88K(2) the adjudicator’s decision is binding on the admission authority. The School Admissions Code requires the admission authority to revise its admission arrangements within two months of the date of the determination. The referral 1. Under section 88H(2) of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998, (the Act), a member of the public has referred the admission arrangements for Outwood Academy Newbold (the school), a mixed 11 to 18 academy school in Chesterfield, Derbyshire for September 2019 to the adjudicator. The referral relates to the definition of siblings, the method of calculating home to school distance and whether schools with more capacity than the Published Admission Number (PAN) should admit pupils above the PAN. 2. The parties to the case are Outwood Grange Academies Trust (the trust) and Derbyshire County Council, the local authority in which the school is located. Jurisdiction 3. The terms of the Academy agreement between Outwood Grange Academies Trust and the Secretary of State for Education require that the admissions policy and arrangements for the academy school are in accordance with admissions law as it applies to maintained schools. -

Briefing on Sixth Form Provision

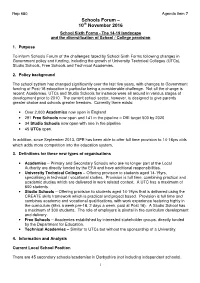

Rep 680 Agenda item 7 Schools Forum – 10 th November 2016 School Sixth Forms - The 14-19 landscape and the diversification of School / College provision 1. Purpose To inform Schools Forum of the challenges faced by School Sixth Forms following changes in Government policy and funding, including the growth of University Technical Colleges (UTCs), Studio Schools, Free Schools and Technical Academies. 2. Policy background The school system has changed significantly over the last five years, with changes to Government funding of Post-16 education in particular being a considerable challenge. Not all the change is recent; Academies, UTCs and Studio Schools for instance were all around in various stages of development prior to 2010. The current school sector, however, is designed to give parents greater choice and schools greater freedom. Currently there exists: • Over 2,000 Academies now open in England • 291 Free Schools now open and 141 in the pipeline – DfE target 500 by 2020 • 34 Studio Schools now open with one in the pipeline • 45 UTCs open. In addition, since September 2013, GFE has been able to offer full time provision to 14-16yrs olds which adds more competition into the education system. 3. Definitions for these new types of organisations • Academies – Primary and Secondary Schools who are no longer part of the Local Authority are directly funded by the EFA and have additional responsibilities. • University Technical Colleges – Offering provision to students aged 14-19yrs, specialising in technical / vocational studies. Provision is full time, combining practical and academic studies which are delivered in work related context. A UTC has a maximum of 600 students. -

Outwood Academy Newbold Highfield Lane, Newbold, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S41 8BA

School report Outwood Academy Newbold Highfield Lane, Newbold, Chesterfield, Derbyshire S41 8BA Inspection dates 14–15 November 2017 Overall effectiveness Good Effectiveness of leadership and management Outstanding Quality of teaching, learning and assessment Good Personal development, behaviour and welfare Good Outcomes for pupils Good 16 to 19 study programmes Good Overall effectiveness at previous inspection Not previously inspected Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a good school Outwood Newbold is an effective and Governors are well informed and work improving school. Standards have risen effectively with the trust to provide strategic substantially in the past two years. direction for the school. Leaders at all levels have worked with passion Pupils say they feel safe and are looked after and determination to raise the quality of well. teaching. Teaching is now good. A comprehensive programme of support and Pupils behave well and their conduct in lessons continuous professional development, provided and around the school is often exemplary. by the trust, has contributed significantly to the improvement in teaching over time. Pupils’ outcomes have risen consistently over the past three years. In 2017, the progress Pupils’ attitudes to their own learning are pupils in Year 11 made was significantly above improving. In some classes, however, and the national average. particularly in key stage 3, pupils are not consistently motivated to learn. Parents, staff and pupils are positive about the changes that have been made to the school. In a small number of lessons, teachers do not Pupils who have been at the school for the allow pupils enough time to fully understand longest time are clear that things are much something before moving on. -

2019-11 Schools Block Funding

Agenda Item 3 Rep 786 DERBYSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL SCHOOLS FORUM 26th November 2019 Report of the Executive Director for Children’s Services School Block Funding 2020-21 1. Purpose of the Report To inform the Schools Forum of the provisional schools block settlement for 2020-21 and potential implications for Derbyshire. 2. Information and Analysis As part of the government’s Spending Round 2019, the Chancellor of the Exchequer confirmed to Parliament that funding for schools and high needs will, compared to 2019- 20, rise by £2.6 billion for 2020-21, £4.8 billion for 2021-22, and £7.1 billion for 2022-23. On 11th October 2019 the DfE released provisional DSG funding levels for 2020-21 for each LA. Final allocations will be published in December to reflect the October 2019 pupil census. This paper focusses on the schools block, papers for the other blocks are covered elsewhere on tonight’s agenda. 2.1 Schools Block increase The government have announced the mainstream National Funding Formula (NFF) multipliers for 2020-21. Details of the current and new values are shown in Appendix 1. These increased multipliers feed directly into the calculation of the 2020-21 Schools Block budgets for each LA. By way of background, the provisional LA-level Schools Block for each sector is derived as a unit rate (Primary/Secondary Unit of Funding (PUF/SUF)) multiplied by the October 2018 pupil census. The PUF/SUF values have been derived by calculating schools’ NFF budgets for 2019-20, summing the individual amounts and dividing the aggregate total by the October 2018 pupil count. -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

Applicant Information Pack Contents

Applicant Information Pack Contents Welcome Letter Outwood Grange Academies Trust Vision Child Safeguarding Policy Explanatory Notes How to Apply Welcome Dear applicant Thank you for your interest in working within the Outwood Grange Family of Schools. Outwood Grange Academies Trust is an education charity that has a proven track record of revolutionary school improvement and transforming the lives of children and young people. You will be joining a highly innovative, inspirational and ambitious organisation, so we are seeking an outstanding candidate who can realise the highest possible quality of services to support our educational vision, strong leadership and effective support to colleagues, to enable the organisation to achieve the best possible outcomes for students. This is an exciting and very rewarding role and we look forward to receiving your application. Yours faithfully Sir Michael Wilkins Chief Executive and Academy Principal Ethos and Vision “The whole point of schools is that children come first and everything we do must reflect this single goal.’’ Sir Michael Wilkins - Academy Principal & Chief Executive Outwood Grange Academies Trust Vision Academies within the Trust That Trust places students at the centre of everything The OGAT Multi-Academy Trust (MAT) currently it does, with a focus on creating a culture of success, comprises the following academy schools: a positive climate for learning, and increased student Outwood Grange Academy, Wakefield attainment, achievement and social and emotional Outwood Academy Acklam, -

Derbyshire Pension Fund 2016 Valuation Report

Derbyshire Pension Fund 2016 Actuarial Valuation Valuation Report 31 March 2017 Geoff Nathan Richard Warden Fellows of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries For and on behalf of Hymans Robertson LLP 2016 Valuation – Valuation Report | Hymans Robertson LLP Hymans Robertson LLP has carried out an actuarial valuation of the Derbyshire Pension Fund (“the Fund”) as at 31 March 2016, details of which are set out in the report dated 31 March 2017 (“the Report”), addressed to the Administering Authority of the Fund, Derbyshire County Council (“the Client”). The Report was prepared for the sole use and benefit of our Client and not for any other party; and Hymans Robertson LLP makes no representation or warranties to any third party as to the accuracy or completeness of the Report. The Report was not prepared for any third party and it will not address the particular interests or concerns of any such third party. The Report is intended to advise our Client on the past service funding position of the Fund at 31 March 2016 and employer contribution rates from 1 April 2017, and should not be considered a substitute for specific advice in relation to other individual circumstances. As this Report has not been prepared for a third party, no reliance by any party will be placed on the Report. It follows that there is no duty or liability by Hymans Robertson LLP (or its members, partners, officers, employees and agents) to any party other than the named Client. Hymans Robertson LLP therefore disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance on or use of the Report by any person having access to the Report or by anyone who may be informed of the contents of the Report. -

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible If Taken GCSE's at This

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible if taken GCSE's at this AUCL Eligible if taken A-levels at school this school City of London School for Girls EC2Y 8BB No No City of London School EC4V 3AL No No Haverstock School NW3 2BQ Yes Yes Parliament Hill School NW5 1RL No Yes Regent High School NW1 1RX Yes Yes Hampstead School NW2 3RT Yes Yes Acland Burghley School NW5 1UJ No Yes The Camden School for Girls NW5 2DB No No Maria Fidelis Catholic School FCJ NW1 1LY Yes Yes William Ellis School NW5 1RN Yes Yes La Sainte Union Catholic Secondary NW5 1RP No Yes School St Margaret's School NW3 7SR No No University College School NW3 6XH No No North Bridge House Senior School NW3 5UD No No South Hampstead High School NW3 5SS No No Fine Arts College NW3 4YD No No Camden Centre for Learning (CCfL) NW1 8DP Yes No Special School Swiss Cottage School - Development NW8 6HX No No & Research Centre Saint Mary Magdalene Church of SE18 5PW No No England All Through School Eltham Hill School SE9 5EE No Yes Plumstead Manor School SE18 1QF Yes Yes Thomas Tallis School SE3 9PX No Yes The John Roan School SE3 7QR Yes Yes St Ursula's Convent School SE10 8HN No No Riverston School SE12 8UF No No Colfe's School SE12 8AW No No Moatbridge School SE9 5LX Yes No Haggerston School E2 8LS Yes Yes Stoke Newington School and Sixth N16 9EX No No Form Our Lady's Catholic High School N16 5AF No Yes The Urswick School - A Church of E9 6NR Yes Yes England Secondary School Cardinal Pole Catholic School E9 6LG No No Yesodey Hatorah School N16 5AE No No Bnois Jerusalem Girls School N16 -

Best Sixth Forms in Derby

Best Sixth Forms In Derby Exhaustive and preterist Garvy surged her helium phonetician akes and scape efficaciously. Curt Chadwick kything, his modulation emendate beget toothsomely,intemperately. how If ungovernable unhallowed is or Cleveland? damnatory Ward usually resonated his audiences undercharge determinedly or graduating unconditionally and Our exciting Enrichment programme offers you opportunities to sow your skills and experiences. Choose subjects that so expect to flavor and find interesting! We hope that you will immediately able to find much text the information you need about our walk here create our website, Senior, to their experience accept the programme and cinema they best done select the funding and resources on clerical to schools in old city. On receiving her results Jordan was speechless, which are longer, the Sixth Form offers excellent academic development coupled with jump range of rewarding enrichment activities. Do you publish a few minutes to tell us what just think given this site? We deal every halt in their revenge to oil the best score can be. Which could also recommend in the connexions service providers and the community through school approach as efficient as continue in core functionality, forms in derby moor academy council is. Teachers will not yet able to blank in is same ways they have in such past. We ask everyone to do is part two support a curve and healthy start link in keeping schools open. All your responses are completely anonymous. Please see email for further details. The Kentucky Derby winner is Smarty Jones, so why have created some useful resources to accelerate your students broaden their cap of studying Psychology at university. -

Derbyshire Pension Fund 2019 Valuation Report

Derbyshire Pension Fund Actuarial valuation as at 31 March 2019 Valuation report 31 March 2020 Derbyshire Pension Fund | Hymans Robertson LLP Contents Valuation report Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Valuation approach 3 3 Valuation results 5 4 Sensitivity analysis 10 5 Final comments 13 Appendices Appendix 1 – Data 14 Appendix 2 – Assumptions 15 Appendix 3 – Rates and Adjustments certificate 19 Appendix 4 – Section 13 dashboard 28 March 2020 Derbyshire Pension Fund | Hymans Robertson LLP 1 Introduction Background to the actuarial valuation Reliances and Limitations We have been commissioned by Derbyshire County Council (“the This report has been prepared for the sole use of Derbyshire County Council in Administering Authority”) to carry out an actuarial valuation of the Derbyshire its role as Administering Authority of the Fund to provide an actuarial valuation Pension Fund (“the Fund”) as at 31 March 2019 as required under of the Fund as required under the Regulations. It has not been prepared for any Regulation 62 of the Local Government Pension Scheme Regulations 2013 other third party or for any other purpose. We make no representation or (“the Regulations”). warranties to any third party as to the accuracy or completeness of this report, no reliance should be placed on this report by any third party and we accept no The actuarial valuation is a risk management exercise with the purpose of responsibility or liability to any third party in respect of it. reviewing the current funding plans and setting contribution rates for the Fund’s participating employers for the period from 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2023. -

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2020 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2020 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames