Trapchi Lhamo Cult in Lhasa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule

TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A COMPILATION OF REFUGEE STATEMENTS 1958-1975 A SERIES OF “EXPERT ON TIBET” PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 TIBET UNDER CHINESE COMMUNIST RULE A Compilation of Refugee Statements 1958-1975 Tibet Under Chinese Communist Rule is a collection of twenty-seven Tibetan refugee statements published by the Information and Publicity Office of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in 1976. At that time Tibet was closed to the outside world and Chinese propaganda was mostly unchallenged in portraying Tibet as having abolished the former system of feudal serfdom and having achieved democratic reforms and socialist transformation as well as self-rule within the Tibet Autonomous Region. Tibetans were portrayed as happy with the results of their liberation by the Chinese Communist Party and satisfied with their lives under Chinese rule. The contrary accounts of the few Tibetan refugees who managed to escape at that time were generally dismissed as most likely exaggerated due to an assumed bias and their extreme contrast with the version of reality presented by the Chinese and their Tibetan spokespersons. The publication of these very credible Tibetan refugee statements challenged the Chinese version of reality within Tibet and began the shift in international opinion away from the claims of Chinese propaganda and toward the facts as revealed by Tibetan eyewitnesses. As such, the publication of this collection of refugee accounts was an important event in the history of Tibetan exile politics and the international perception of the Tibet issue. The following is a short synopsis of the accounts. -

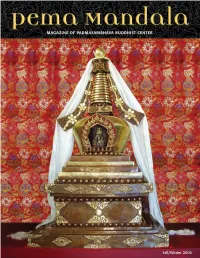

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Compassion & Social Justice

COMPASSION & SOCIAL JUSTICE Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo PUBLISHED BY Sakyadhita Yogyakarta, Indonesia © Copyright 2015 Karma Lekshe Tsomo No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the editor. CONTENTS PREFACE ix BUDDHIST WOMEN OF INDONESIA The New Space for Peranakan Chinese Woman in Late Colonial Indonesia: Tjoa Hin Hoaij in the Historiography of Buddhism 1 Yulianti Bhikkhuni Jinakumari and the Early Indonesian Buddhist Nuns 7 Medya Silvita Ibu Parvati: An Indonesian Buddhist Pioneer 13 Heru Suherman Lim Indonesian Women’s Roles in Buddhist Education 17 Bhiksuni Zong Kai Indonesian Women and Buddhist Social Service 22 Dian Pratiwi COMPASSION & INNER TRANSFORMATION The Rearranged Roles of Buddhist Nuns in the Modern Korean Sangha: A Case Study 2 of Practicing Compassion 25 Hyo Seok Sunim Vipassana and Pain: A Case Study of Taiwanese Female Buddhists Who Practice Vipassana 29 Shiou-Ding Shi Buddhist and Living with HIV: Two Life Stories from Taiwan 34 Wei-yi Cheng Teaching Dharma in Prison 43 Robina Courtin iii INDONESIAN BUDDHIST WOMEN IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Light of the Kilis: Our Javanese Bhikkhuni Foremothers 47 Bhikkhuni Tathaaloka Buddhist Women of Indonesia: Diversity and Social Justice 57 Karma Lekshe Tsomo Establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha in Indonesia: Obstacles and -

17-Point Agreement of 1951 by Song Liming

FACTS ABOUT THE 17-POINT “Agreement’’ Between Tibet and China Dharamsala, 22 May 22 DIIR PUBLICATIONS The signed articles in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the Central Tibetan Administration. This report is compiled and published by the Department of Information and International Relations, Central Tibetan Administration, Gangchen Kyishong, Dharamsala 176 215, H. P., INDIA Email: [email protected] Website: www.tibet.net and ww.tibet.com CONTENTS Part One—Historical Facts 17-point “Agreement”: The full story as revealed by the Tibetans and Chinese who were involved Part Two—Scholars’ Viewpoint Reflections on the 17-point Agreement of 1951 by Song Liming The “17-point Agreement”: Context and Consequences by Claude Arpi The Relevance of the 17-point Agreement Today by Michael van Walt van Praag Tibetan Tragedy Began with a Farce by Cao Changqing Appendix The Text of the 17-point Agreement along with the reproduction of the original Tibetan document as released by the Chinese government His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Press Statements on the “Agreement” FORWARD 23 May 2001 marks the 50th anniversary of the signing of the 17-point Agreement between Tibet and China. This controversial document, forced upon an unwilling but helpless Tibetan government, compelled Tibet to co-exist with a resurgent communist China. The People’s Republic of China will once again flaunt this dubious legal instrument, the only one China signed with a “minority” people, to continue to legitimise its claim on the vast, resource-rich Tibetan tableland. China will use the anniversary to showcase its achievements in Tibet to justify its continued occupation of the Tibetan Plateau. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Japanese Visitors to Tibet in the Early 20Th Century and Their Impact on Tibetan Military Affairs—With a Focus on Yasujirō Yajima*

Japanese Visitors to Tibet in the Early 20th Century and their Impact on Tibetan Military Affairs—with a Focus on Yasujirō Yajima* Yasuko Komoto (Hokkaido University) ittle information has been so far been made available in west- L ern language literature on Tibet concerning the Japanese mil- itary instructor Yasujirō Yajima (1882–1963, see Photograph 1) who stayed in Tibet between 1912 and 1918. He is known for having been among the instructors entrusted by the government of Tibet with the training of the Tibetan army in the context of modernisation re- forms undertaken by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama after 1913. Two eye- witness accounts of him by Tibetans have come down to us, the first by the historian Shakabpa (1907–1989): Under the auspices of Japan’s ambassador in Beijing, Gonsuke Hayashe, a retired Japanese military officer named Yasujiro Yajima ar- rived in Lhasa by way of Kham in 1913. He trained a regiment of the Tibetan army according to Japanese military customs. During his six- year stay in Lhasa, he tied his hair (in the Tibetan manner) and attended all of the ceremonies, just like the Tibetan government officials. He also constructed the camp of the Dalai Lama’s bodyguard in the Japanese style.1 The second account is by the Tibetan army General Tsarong Dasang Dadul (Tsha rong zla bzang dgra ’dul, 1888–1959), as recounted in the biography by his son: * The research for this article has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement 677952 “TibArmy”). -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

Konzerte Spielzeit Januar – Juni 2020 20 Jahre

KONZERTE SPIELZEIT JANUAR – JUNI 2020 20 JAHRE NRW-NETZWERK GLOBALER MUSIK BERGKAMEN BIELEFELD BOCHOLT BONN BRILON DETMOLD DÜSSELDORF GELSENKIRCHEN GÜTERSLOH HAMM HERNE KEMPEN KÖLN MESCHEDE MÜNSTER PADERBORN REMSCHEID SIEGEN SOLINGEN WUPPERTAL BRÜSSEL | BELGIEN LEIDEN | NIEDERLANDE KONZERTE JANUAR – JUNI 2020 LEE NARAE PALVAN HAMIDOV 09.01.2020 REMSCHEID 15.04.2020 DÜSSELDORF 10.01.2020 DETMOLD 19.04.2020 PADERBORN 13.01.2020 GÜTERSLOH 20.04.2020 SIEGEN 14.01.2020 HAMM 21.04.2020 HAMM 15.01.2020 DÜSSELDORF 22.04.2020 KÖLN 16.01.2020 WUPPERTAL 23.04.2020 GÜTERSLOH 19.01.2020 SOLINGEN 24.04.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 20.01.2020 SIEGEN 25.04.2020 LEIDEN 22.01.2020 KÖLN 23.01.2020 KEMPEN NIYIRETH ALARCÓN 10.05.2020 PADERBORN LO CÒR DE LA PLANA 11.05.2020 BERGKAMEN 05.02.2020 DÜSSELDORF 13.05.2020 KÖLN 08.02.2020 MESCHEDE 14.05.2020 WUPPERTAL 12.02.2020 GÜTERSLOH 17.05.2020 BRILON 13.02.2020 WUPPERTAL 18.05.2020 SIEGEN 14.02.2020 DETMOLD 19.05.2020 HAMM 16.02.2020 SOLINGEN 20.05.2020 DÜSSELDORF 17.02.2020 SIEGEN 22.05.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 18.02.2020 HAMM 25.05.2020 BOCHOLT 19.02.2020 KÖLN 26.05.2020 HERNE 21.02.2020 BRÜSSEL 27.05.2020 KEMPEN 28.05.2020 REMSCHEID SAFAR 12.03.2020 REMSCHEID TAMALA 13.03.2020 DETMOLD 01.06.2020 DETMOLD 15.03.2020 BRILON 03.06.2020 DÜSSELDORF 16.03.2020 BERGKAMEN 04.06.2020 HERNE 17.03.2020 HAMM 07.06.2020 BONN 18.03.2020 DÜSSELDORF 08.06.2020 BERGKAMEN 19.03.2020 WUPPERTAL 14.06.2020 PADERBORN 21.03.2020 LEIDEN 16.06.2020 HAMM 22.03.2020 PADERBORN 17.06.2020 KÖLN 23.03.2020 BOCHOLT 18.06.2020 WUPPERTAL 24.03.2020 GÜTERSLOH 19.06.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 25.03.2020 KÖLN 20.06.2020 MÜNSTER 26.03.2020 BONN 27.03.2020 GELSENKIRCHEN 28.03.2020 BRÜSSEL 29.03.2020 KEMPEN ALLE TERMINE AUCH AUF 31.03.2020 HERNE www.klangkosmos-nrw.de VORWORT Klangkosmos NRW hat Geburtstag! Im Januar 2000 fand das erste Konzert unter dem Label „Klangkosmos“ in Köln statt. -

During the Ganden Phodrang Period (1642-1959)

MILITARY CULTURE IN TIBET DURING THE GANDEN PHODRANG PERIOD (1642-1959): THE INTERACTION BETWEEN TIBETAN AND OTHER ASIAN MILITARY TRADITIONS MONDAY 18TH, JUNE 2018 WOLFSON COLLEGE, HALDANE ROOM LINTON ROAD, OXFORD OX2 6UD MORNING 09.00 Tea/Coffee 09.15 Welcome by Ulrike Roesler (Oriental Institute, Oxford) 09.30 The History of Tibet’s Military Relations with her Neighbours from the 17th to 20th Centuries: An Overview George FitzHerbert and Alice Travers (CNRS, CRCAO, Paris) SEVENTEENTH AND EIGHTEENTH CENTURIES Chair: Nicola Di Cosmo (Institute for Advance Study, Princeton) 10.00 A Tibetan Banner System? Making Sense of the Tibetan Military Institution during the 17th and 18th Centuries Qichen (Barton) Qian (Columbia University, New York) 10.30 Mongol and Tibetan Armies on the Transhimalayan Fronts in the Second Half of the 17th Century Federica Venturi (CNRS, CRCAO, Paris) 11.00 Tea/Coffee 11.15 Zunghar Military Techniques and Strategies in Tibet Hosung Shim (Indiana University, Bloomington) 11.45 Tibetan and Qing Troops in the Gurkha Wars (1788-1792) Ulrich Theobald (Tubingen University, Tubingen) 12.15-14.00 Lunch for all participants at Wolfson College AFTERNOON NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES Chair: Charles Ramble (EPHE, CRCAO, Paris) 14.00 Qing Garrison Temples in Tibet and the Cultural Politics of the Guandi/Gesar Synthesis in Inner Asia George FitzHerbert (CNRS, CRCAO, Paris) 14.30 The Career of a Tibetan Army General, Zur khang Sri gcod tshe brtan, after the 1793 Manchu Military Reforms Alice Travers (CNRS, CRCAO, Paris) 15.00 -

A Sorrowful Song to Palden Lhamo Kün-Kyab Tro

A SORROWFUL SONG TO PALDEN LHAMO KÜN-KYAB TRO- DREL A PRAISE BY HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA Expanse of great bliss, all-pervading, free from elaborations, with either angry or desirous forms related to those to be subdued. You overpower the whole apparent world, samsara and nirvana. Sole mother, lady victorious over the three worlds, please pay attention here and now! During numberless eons, By relying upon and accustoming yourself to the extensive conduct of the bodhisattvas, which others find difficult to follow, you obtained the power of the sublime vajra enlightenment; loving mother, you watch and don’t miss the [right] time. The winds of conceptuality dissolve into space. Vajra-dance of the mind that produces all the animate and inanimate world, as the sole friend yielding the pleasures of existence and peace, having conquered them all, you are well praised as the triumphant mother. By heroically guarding the Dharma and dharma- holders, with the four types of actions, flashing like lightning, You soar up openly, like the full moon in the midst of a garland of powerful Dharma protectors. When from the troublesome nature of this most degenerated time The hosts of evil omens — desire, anger, ignorance — increasingly rise, even then your power is unimpeded, sharp, swift and limitless. How wonderful! Longingly remembering you, O Goddess, from my heart, I confess my broken vows and satisfy all your pleasures. Having enthroned you as the supreme protector, greatest among the great, accomplish your appointed tasks with unflinching energy! Fierce protecting deities and your retinues who, in accordance with the instructions of the supreme siddha, the lotus-born vajra, and by the power of karma and prayers, have a close connection as guardians of Tibet, heighten your majesty and increase your powers! All beings in the country of Tibet, although destroyed by the enemy and tormented by unbearable suffering, abide in the constant hope of glorious freedom. -

High Peaks, Pure Earth

BOOK REVIEW HIGH PEAKS, PURE EARTH COLLECTED WRITINGS ON TIBETAN HISTORY AND CULTURE BY HUGH RICHARDSON A COMPILATION OF A SERIES OF PROGRAMS ON RADIO FREE ASIA TIBETAN SERVICE BY WARREN W. SMITH 1 HIGH PEAKS, PURE EARTH High Peaks, Pure Earth is the title of the collected works on Tibetan history and culture by Hugh Richardson, a British diplomat who became a historian of Tibet. He was British representative in Lhasa from 1936 to 1940 and again from 1946 to 1950, during which time he did many studies on ancient and modern Tibetan history. He wrote numerous articles on Tibetan history and culture, all of which have been published in this book of his collected writings. Hugh Richardson was born in Scotland, a part of Great Britain that bears some similarities to Tibet, both in its environment and in its politics. Scotland has long had a contentious relationship with England and was incorporated only by force into Great Britain. Richardson became a member of the British administration of India in 1932. He was a member of a 1936 British mission to Tibet. Richardson remained in Lhasa to become the first officer in charge of the British Mission in Lhasa. He was in Lhasa from 1936 to 1940, when the Second World War began. After the war he again represented the British Government in Lhasa from 1946 to 1947, when India became independent, after which he was the representative of the Government of India. He left Tibet only in September 1950, shortly before the Chinese invasion. Richardson lived in Tibet for a total of eight years. -

The Dalai Lama

THE INSTITUTION OF THE DALAI LAMA 1 THE DALAI LAMAS 1st Dalai Lama: Gendun Drub 8th Dalai Lama: Jampel Gyatso b. 1391 – d. 1474 b. 1758 – d. 1804 Enthroned: 1762 f. Gonpo Dorje – m. Jomo Namkyi f. Sonam Dargye - m. Phuntsok Wangmo Birth Place: Sakya, Tsang, Tibet Birth Place: Lhari Gang, Tsang 2nd Dalai Lama: Gendun Gyatso 9th Dalai Lama: Lungtok Gyatso b. 1476 – d. 1542 b. 1805 – d. 1815 Enthroned: 1487 Enthroned: 1810 f. Kunga Gyaltsen - m. Kunga Palmo f. Tenzin Choekyong Birth Place: Tsang Tanak, Tibet m. Dhondup Dolma Birth Place: Dan Chokhor, Kham 3rd Dalai Lama: Sonam Gyatso b. 1543 – d. 1588 10th Dalai Lama: Tsultrim Gyatso Enthroned: 1546 b. 1816 – d. 1837 f. Namgyal Drakpa – m. Pelzom Bhuti Enthroned: 1822 Birth Place: Tolung, Central Tibet f. Lobsang Drakpa – m. Namgyal Bhuti Birth Place: Lithang, Kham 4th Dalai Lama: Yonten Gyatso b. 1589 – d. 1617 11th Dalai Lama: Khedrub Gyatso Enthroned: 1601 b. 1838– d. 1855 f. Sumbur Secen Cugukur Enthroned 1842 m. Bighcogh Bikiji f. Tseten Dhondup – m. Yungdrung Bhuti Birth Place: Mongolia Birth Place: Gathar, Kham 5th Dalai Lama: 12th Dalai Lama: Trinley Gyatso Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso b. 1856 – d. 1875 b. 1617 – d. 1682 Enthroned: 1860 Enthroned: 1638 f. Phuntsok Tsewang – m. Tsering Yudon f. Dudul Rapten – m. Kunga Lhadze Birth Place: Lhoka Birth Place: Lhoka, Central Tibet 13th Dalai Lama: Thupten Gyatso 6th Dalai Lama: Tseyang Gyatso b. 1876 – d. 1933 b. 1683 – d. 1706 Enthroned: 1879 Enthroned: 1697 f. Kunga Rinchen – m. Lobsang Dolma f. Tashi Tenzin – m. Tsewang Lhamo Birth Place: Langdun, Central Tibet Birth Place: Mon Tawang, India 14th Dalai Lama: Tenzin Gyatso 7th Dalai Lama: Kalsang Gyatso b.