Zootaxa,The Phylum Cnidaria: a Review Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity and Community Structure of Pelagic Cnidarians in the Celebes and Sulu Seas, Southeast Asian Tropical Marginal Seas

Deep-Sea Research I 100 (2015) 54–63 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Deep-Sea Research I journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dsri Diversity and community structure of pelagic cnidarians in the Celebes and Sulu Seas, southeast Asian tropical marginal seas Mary M. Grossmann a,n, Jun Nishikawa b, Dhugal J. Lindsay c a Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), Tancha 1919-1, Onna-son, Okinawa 904-0495, Japan b Tokai University, 3-20-1, Orido, Shimizu, Shizuoka 424-8610, Japan c Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Yokosuka 237-0061, Japan article info abstract Article history: The Sulu Sea is a semi-isolated, marginal basin surrounded by high sills that greatly reduce water inflow Received 13 September 2014 at mesopelagic depths. For this reason, the entire water column below 400 m is stable and homogeneous Received in revised form with respect to salinity (ca. 34.00) and temperature (ca. 10 1C). The neighbouring Celebes Sea is more 19 January 2015 open, and highly influenced by Pacific waters at comparable depths. The abundance, diversity, and Accepted 1 February 2015 community structure of pelagic cnidarians was investigated in both seas in February 2000. Cnidarian Available online 19 February 2015 abundance was similar in both sampling locations, but species diversity was lower in the Sulu Sea, Keywords: especially at mesopelagic depths. At the surface, the cnidarian community was similar in both Tropical marginal seas, but, at depth, community structure was dependent first on sampling location Marginal sea and then on depth within each Sea. Cnidarians showed different patterns of dominance at the two Sill sampling locations, with Sulu Sea communities often dominated by species that are rare elsewhere in Pelagic cnidarians fi Community structure the Indo-Paci c. -

High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project

High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project AEA Technology, Environment Contract: W/35/00632/00/00 For: The Department of Trade and Industry New & Renewable Energy Programme Report issued 30 August 2002 (Version with minor corrections 16 September 2002) Keith Hiscock, Harvey Tyler-Walters and Hugh Jones Reference: Hiscock, K., Tyler-Walters, H. & Jones, H. 2002. High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project. Report from the Marine Biological Association to The Department of Trade and Industry New & Renewable Energy Programme. (AEA Technology, Environment Contract: W/35/00632/00/00.) Correspondence: Dr. K. Hiscock, The Laboratory, Citadel Hill, Plymouth, PL1 2PB. [email protected] High level environmental screening study for offshore wind farm developments – marine habitats and species ii High level environmental screening study for offshore wind farm developments – marine habitats and species Title: High Level Environmental Screening Study for Offshore Wind Farm Developments – Marine Habitats and Species Project. Contract Report: W/35/00632/00/00. Client: Department of Trade and Industry (New & Renewable Energy Programme) Contract management: AEA Technology, Environment. Date of contract issue: 22/07/2002 Level of report issue: Final Confidentiality: Distribution at discretion of DTI before Consultation report published then no restriction. Distribution: Two copies and electronic file to DTI (Mr S. Payne, Offshore Renewables Planning). One copy to MBA library. Prepared by: Dr. K. Hiscock, Dr. H. Tyler-Walters & Hugh Jones Authorization: Project Director: Dr. Keith Hiscock Date: Signature: MBA Director: Prof. S. Hawkins Date: Signature: This report can be referred to as follows: Hiscock, K., Tyler-Walters, H. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

BIO 221 Invertebrate Zoology I Spring 2010

BIO 221 Invertebrate Zoology I Spring 2010 Stephen M. Shuster Northern Arizona University http://www4.nau.edu/isopod Lecture 10 From Collins et al. 2006 From Collins et al. 2006 1 Cnidarian Classes Hydrozoa Scyphozoa Medusozoa Cubozoa Stauromedusae Anthozoa Class Hydrozoa 1.Includes over 2,700 species, many freshwater. 2. Generally thought to be most ancestral, but recent DNA evidence suggests this may not be so. Class Hydrozoa Trachyline Hydrozoa seem most ancestral – within the Hydrozoa. 1. seem to have mainly medusoid life stage 2. character (1): assumption of metagenesis 2 Class Hydrozoa Trachyline Hydrozoa seem most ancestral. 1. seem to have mainly medusoid life stage 2. character (1): assumption of metagenesis Class Hydrozoa Other autapomorphies (see lab manual): i. 4 rayed symmetry. ii. ectodermal gonads iii. medusae with velum. iv. no gastric septa v. external skeleton if present. vi. no stomadaeum vii. freshwater or marine habitats. Class Hydrozoa - 7 Orders 1. Order Trachylina - reduced polyps, probably polyphyletic . Voragonema pedunculata, collected by submersible at about 2700' deep in the Bahamas. 3 Class Hydrozoa - 7 Orders 2. Order Hydroida - the "seaweeds.“ a. Suborder Anthomedusae - also Athecata, Aplanulata, Capitata. b. Suborder Leptomedusae - also Thecata Class Hydrozoa - 7 Orders 3. Order Miliporina - fire corals. 4. Order Stylasterina - similar to fire corals; hold medusae. 4 Class Hydrozoa - 7 Orders 5. Order Siphonophora - floating colonies of polyps and medusae. Class Hydrozoa - 7 Orders 6. Order Chondrophora - floating colonies of polyps Class Hydrozoa - 7 Orders 7. Order Actinulida (Aplanulata)- solitary polyps, no medusae, no planulae 5 Order Trachylina Trachymedusae includes Lirope a. resemble the medusae of Gonionemus, 1. -

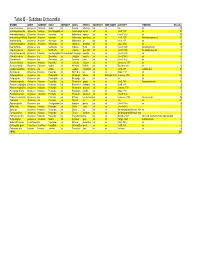

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia BINOMEN ORDER SUBORDER FAMILY SUBFAMILY GENUS SPECIES SUBSPECIES COMN_NAMES AUTHORITY SYNONYMS #Records Acanella arbuscula Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Acanella arbuscula n/a n/a n/a n/a 59 Acanthogorgia armata Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae n/a Acanthogorgia armata n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 95 Anthomastus agassizii Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 35 Anthomastus grandiflorus Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus grandiflorus n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 Anthomastus purpureus 37 Anthomastus sp. Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus sp. n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 1 Anthothela grandiflora Alcyonacea Scleraxonia Anthothelidae n/a Anthothela grandiflora n/a n/a (Sars, 1856) n/a 24 Capnella florida Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella florida n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya florida 44 Capnella glomerata Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella glomerata n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya glomerata 4 Chrysogorgia agassizii Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae Chrysogorgiidae Chrysogorgia agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1883) n/a 2 Clavularia modesta Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia modesta n/a n/a (Verrill, 1987) n/a 6 Clavularia rudis Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia rudis n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 1 Gersemia fruticosa Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Gersemia fruticosa n/a n/a Marenzeller, 1877 n/a 3 Keratoisis flexibilis Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Keratoisis flexibilis n/a n/a Pourtales, 1868 n/a 1 Lepidisis caryophyllia Alcyonacea n/a Isididae n/a Lepidisis caryophyllia n/a n/a Verrill, 1883 Lepidisis vitrea 13 Muriceides sp. -

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS of the 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project

DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project March 2018 DEEP SEA LEBANON RESULTS OF THE 2016 EXPEDITION EXPLORING SUBMARINE CANYONS Towards Deep-Sea Conservation in Lebanon Project Citation: Aguilar, R., García, S., Perry, A.L., Alvarez, H., Blanco, J., Bitar, G. 2018. 2016 Deep-sea Lebanon Expedition: Exploring Submarine Canyons. Oceana, Madrid. 94 p. DOI: 10.31230/osf.io/34cb9 Based on an official request from Lebanon’s Ministry of Environment back in 2013, Oceana has planned and carried out an expedition to survey Lebanese deep-sea canyons and escarpments. Cover: Cerianthus membranaceus © OCEANA All photos are © OCEANA Index 06 Introduction 11 Methods 16 Results 44 Areas 12 Rov surveys 16 Habitat types 44 Tarablus/Batroun 14 Infaunal surveys 16 Coralligenous habitat 44 Jounieh 14 Oceanographic and rhodolith/maërl 45 St. George beds measurements 46 Beirut 19 Sandy bottoms 15 Data analyses 46 Sayniq 15 Collaborations 20 Sandy-muddy bottoms 20 Rocky bottoms 22 Canyon heads 22 Bathyal muds 24 Species 27 Fishes 29 Crustaceans 30 Echinoderms 31 Cnidarians 36 Sponges 38 Molluscs 40 Bryozoans 40 Brachiopods 42 Tunicates 42 Annelids 42 Foraminifera 42 Algae | Deep sea Lebanon OCEANA 47 Human 50 Discussion and 68 Annex 1 85 Annex 2 impacts conclusions 68 Table A1. List of 85 Methodology for 47 Marine litter 51 Main expedition species identified assesing relative 49 Fisheries findings 84 Table A2. List conservation interest of 49 Other observations 52 Key community of threatened types and their species identified survey areas ecological importanc 84 Figure A1. -

The Genetic Identity of Dinoflagellate Symbionts in Caribbean Octocorals

Coral Reefs (2004) 23: 465-472 DOI 10.1007/S00338-004-0408-8 REPORT Tamar L. Goulet • Mary Alice CofFroth The genetic identity of dinoflagellate symbionts in Caribbean octocorals Received: 2 September 2002 / Accepted: 20 December 2003 / Published online: 29 July 2004 © Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract Many cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea Introduction anemones) maintain a symbiosis with dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae). Zooxanthellae are grouped into The cornerstone of the coral reef ecosystem is the sym- clades, with studies focusing on scleractinian corals. biosis between cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea We characterized zooxanthellae in 35 species of Caribbean octocorals. Most Caribbean octocoral spe- anemones) and unicellular dinoñagellates commonly called zooxanthellae. Studies of zooxanthella symbioses cies (88.6%) hosted clade B zooxanthellae, 8.6% have previously been hampered by the difficulty of hosted clade C, and one species (2.9%) hosted clades B and C. Erythropodium caribaeorum harbored clade identifying the algae. Past techniques relied on culturing and/or identifying zooxanthellae based on their free- C and a unique RFLP pattern, which, when se- swimming form (Trench 1997), antigenic features quenced, fell within clade C. Five octocoral species (Kinzie and Chee 1982), and cell architecture (Blank displayed no zooxanthella cladal variation with depth. 1987), among others. These techniques were time-con- Nine of the ten octocoral species sampled throughout suming, required a great deal of expertise, and resulted the Caribbean exhibited no regional zooxanthella cla- in the differentiation of only a small number of zoo- dal differences. The exception, Briareum asbestinum, xanthella species. Molecular techniques amplifying had some colonies from the Dry Tortugas exhibiting zooxanthella DNA encoding for the small and large the E. -

The Histology of Nanomia Bijuga (Hydrozoa: Siphonophora) SAMUEL H

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Histology of Nanomia bijuga (Hydrozoa: Siphonophora) SAMUEL H. CHURCH*, STEFAN SIEBERT, PATHIKRIT BHATTACHARYYA, AND CASEY W. DUNN Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island ABSTRACT The siphonophore Nanomia bijuga is a pelagic hydrozoan (Cnidaria) with complex morphological organization. Each siphonophore is made up of many asexually produced, genetically identical zooids that are functionally specialized and morphologically distinct. These zooids predominantly arise by budding in two growth zones, and are arranged in precise patterns. This study describes the cellular anatomy of several zooid types, the stem, and the gas-filled float, called the pneumatophore. The distribution of cellular morphologies across zooid types enhances our understanding of zooid function. The unique absorptive cells in the palpon, for example, indicate specialized intracellular digestive processing in this zooid type. Though cnidarians are usually thought of as mono-epithelial, we characterize at least two cellular populations in this species which are not connected to a basement membrane. This work provides a greater understanding of epithelial diversity within the cnidarians, and will be a foundation for future studies on N. bijuga, including functional assays and gene expression analyses. J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.) 324B:435– 449, 2015. © 2015 The Authors. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and J. Exp. Zool. Developmental Evolution Published by Wiley Periodicals, Inc. (Mol. Dev. Evol.) 324B:435–449, How to cite this article: Church SH, Siebert S, Bhattacharyya P, Dunn CW. 2015. The histology of 2015 Nanomia bijuga (Hydrozoa: Siphonophora). J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.) 324B:435–449. Siphonophores are pelagic hydrozoans (Cnidaria) with a highly and defense (Dunn and Wagner, 2006; Totton, '65). -

166, December 2016

PSAMMONALIA The Newsletter of the International Association of Meiobenthologists Number 166, December 2016 Composed and Printed at: Lab. Of Biodiversity Dept. Of Life Science, College of Natural Sciences, Hanyang University, 222 Wangsimni–ro, Seongdong-gu, Seoul, 04763, Korea. Remembering the good times. Season’s Greetings, and Happy New Year! (2017) DONT FORGET TO RENEW YOUR MEMBERSHIP IN IAM! THE APPLICATION CAN BE FOUND AT: http://www.meiofauna.org/appform.html This newsletter is mailed electronically. Paper copies will be sent only upon request This Newsletter is not part of the scientific literature for taxonomic purposes 1 The International Association of Meiobenthologists Executive Committee Vadim Mokievsky P.P. Shirshov Institute of Oceanology, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chairperson 36 Nakhimovskiy Prospect, 117218 Moscow, Russia [[email protected]] Wonchoel Lee Lab. of Biodiversity, (#505), Department of Life Science, Past Chairperson College of Natural Sciences, Hanyang University. [[email protected]] Ann Vanreusel Ghent University, Biology Department, Marine Biology Section, Gent, Treasurer B-9000, Belgium [[email protected]] Jyotsna Sharma Department of Biology, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Asistant Treasurer TX 78249-0661, USA [[email protected]] Hanan Mitwally Faculty of Science, Oceanography, University of Alexandria, (Term expires 2019) Moharram Bay, 21151, Egypt. [[email protected]] Gustavo Fonseca Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Instituto do Mar, Av. AlmZ Saldanha (Term expires 2019) da Gama 89, 11030-400 Santos, Brazil. [[email protected]] Daniel Leduc National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, (Term expires 2022) Private Bag 14-901, Wellington, New Zealand [[email protected]] Nabil Majdi Bielefeld University, Animal Ecology, Konsequenz 45, 33615, Bielefeld, (Term expires 2022) Germany [[email protected]] Ex-Officio Executive Committee (Past Chairpersons) 1966-67 Robert Higgins (Founding Editor) 1987-89 John Fleeger 1968-69 W. -

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES an Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals

OREGON ESTUARINE INVERTEBRATES An Illustrated Guide to the Common and Important Invertebrate Animals By Paul Rudy, Jr. Lynn Hay Rudy Oregon Institute of Marine Biology University of Oregon Charleston, Oregon 97420 Contract No. 79-111 Project Officer Jay F. Watson U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 500 N.E. Multnomah Street Portland, Oregon 97232 Performed for National Coastal Ecosystems Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 Table of Contents Introduction CNIDARIA Hydrozoa Aequorea aequorea ................................................................ 6 Obelia longissima .................................................................. 8 Polyorchis penicillatus 10 Tubularia crocea ................................................................. 12 Anthozoa Anthopleura artemisia ................................. 14 Anthopleura elegantissima .................................................. 16 Haliplanella luciae .................................................................. 18 Nematostella vectensis ......................................................... 20 Metridium senile .................................................................... 22 NEMERTEA Amphiporus imparispinosus ................................................ 24 Carinoma mutabilis ................................................................ 26 Cerebratulus californiensis .................................................. 28 Lineus ruber ......................................................................... -

New Species of Stylasterid (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa: Anthoathecata: Stylasteridae) from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Author(S): Stephen D

New Species of Stylasterid (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa: Anthoathecata: Stylasteridae) from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Author(s): Stephen D. Cairns Source: Pacific Science, 71(1):77-81. Published By: University of Hawai'i Press DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2984/71.1.7 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2984/71.1.7 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. New Species of Stylasterid (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa: Anthoathecata: Stylasteridae) from the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands1 Stephen D. Cairns 2 Abstract: A new species of Crypthelia, C. kelleyi, is described from a seamount in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, making it the fifth species of stylasterid known from the Hawaiian Islands. Collected at 2,116 m, it is the fourth-deepest stylasterid species known. Once thought to be absent from Hawai- materials and methods ian waters (Boschma 1959), four stylasterid species have been reported from this archi- The specimen was collected on the Okeanos pelago, primarily on seamounts and off small Explorer expedition to the Northwestern islands in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Hawaiian Islands, which took place in August at depths of 293 – 583 m (Cairns 2005). -

A Case Study with the Monospecific Genus Aegina

MARINE BIOLOGY RESEARCH, 2017 https://doi.org/10.1080/17451000.2016.1268261 ORIGINAL ARTICLE The perils of online biogeographic databases: a case study with the ‘monospecific’ genus Aegina (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa, Narcomedusae) Dhugal John Lindsaya,b, Mary Matilda Grossmannc, Bastian Bentlaged,e, Allen Gilbert Collinsd, Ryo Minemizuf, Russell Ross Hopcroftg, Hiroshi Miyakeb, Mitsuko Hidaka-Umetsua,b and Jun Nishikawah aEnvironmental Impact Assessment Research Group, Research and Development Center for Submarine Resources, Japan Agency for Marine- Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), Yokosuka, Japan; bLaboratory of Aquatic Ecology, School of Marine Bioscience, Kitasato University, Sagamihara, Japan; cMarine Biophysics Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), Onna, Japan; dDepartment of Invertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA; eMarine Laboratory, University of Guam, Mangilao, USA; fRyo Minemizu Photo Office, Shimizu, Japan; gInstitute of Marine Science, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska, USA; hDepartment of Marine Biology, Tokai University, Shizuoka, Japan ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Online biogeographic databases are increasingly being used as data sources for scientific papers Received 23 May 2016 and reports, for example, to characterize global patterns and predictors of marine biodiversity and Accepted 28 November 2016 to identify areas of ecological significance in the open oceans and deep seas. However, the utility RESPONSIBLE EDITOR of such databases is entirely dependent on the quality of the data they contain. We present a case Stefania Puce study that evaluated online biogeographic information available for a hydrozoan narcomedusan jellyfish, Aegina citrea. This medusa is considered one of the easiest to identify because it is one of KEYWORDS very few species with only four large tentacles protruding from midway up the exumbrella and it Biogeography databases; is the only recognized species in its genus.