The Canary Island Texans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encountering Nicaragua

Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Spring 2011 ii Encountering Nicaragua United States Marines Occupying Nicaragua, 1927-1933 Christian Laupsa MA Thesis in History Department of Archeology, Conservation, and History University of Oslo Spring 2011 iii iv Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................... v Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... viii 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Topic .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Research Questions ............................................................................................................................. 3 Delimitations ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The United States Marine Corps: a very brief history ......................................................................... 4 Historiography .................................................................................................................................... -

The Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase In 1803, the United States bought the Louisiana Territory from France, which was in dire straits following their revolution. On the Lewis and Clark site, there is this map of the Louisiana Purchase. As you can see, there was a great deal more of what is now the United States that was not settled. Look at Spanish Florida, New Spain, Oregon Country and British North America. The North West had been the habitat of fur traders, mostly from the British Isles, for many years. Meanwhile, in the South, there was the desire to expel the Spanish from Florida. As American expansionism moved the boundaries further west and south, the British pushed back. Greatness of the Port of New Orleans dates back to the Revolution when the Ohio River Valley was settled, and the settlers had no other way to market their produce then down the river to New Orleans – then a Spanish Port. First they came on rafts then flatboats, and, finally keelboats which could be poled back up the river. (Rafts and flatboats were broken up and the timber sold.) In the early years of this river traffic, tough American boatmen had many a argument with Spanish troops of New Orleans. Here we see Governor Milo halting once such argument. Miro hoped to persuade Tennessee and Kentucky to secede from the United States and join Spanish Louisiana. Instead, the valleyfolks brought such pressure on President Thomas Jefferson that the Louisiana Purchase resulted. An indication of the volume of this early trade between the Americans and the Spaniards at New Orleans is the American dollar. -

DEL ESTADO Adminiración Y Venta De Ejemlapres: Precio Del Ejemiilar: 0'25 Ptas

OFICIAl DEL ESTADO Adminiración y venta de ejemlapres: Precio del ejemiilar: 0'25 ptas. Puebla, 23 = BURGOS = Teléfono 1238 Atrasado: 0'50 ptas. IÑOIII.—NÚM. 593: MARTES, 7 JUNIO 1938.—II AÑO TRIUNFAL PÁGINA 7737J SUMARIO ! Escuela Normal del Magisterio Destinos Primario de Pontevedrv.—^Página 7740. Orden asignando los destinos que in- MINISTERIO DE ASUNTOS dica a los Jefes y Oficiales de In- EXTERIORES fantería D. Enrique Pata Gil y MINISTERIO DE QRDEN otros.—Página 7744. fWlo nombrando primer Secretarlo PUBLICO ^ Otra id. a los de Caballería D. José \ m k Embajada de España en ta Iñigo Bravo y otros. — Página l Santa Sede a D. Antonio de ía Orden disponiendo la separación del 7744. Cierna letüí'fa.—Página 7738, Cuerpo y su baja en el Escalafón ira ¡i Secretario de primera clase de los Guardias de Seguridad y Otra id. id. a D. Pedro Alcorta Ur- en k Embajada de España en Lis- Asalto Manuel González Canseco y quijo y otros.—Páginas 7744 y i boa a D. Alvaro Seminario y Mar- otros.—Página 7740. 7745. .tinez,—^Página 7738. Otra id. la id. del id. y su id. en el Otra id. a los de Artillería D. Casi- id. de los Guardias Antonio Castro miro Roda Diana y otros.-—^Pági- na 7745. |J«INISTTNIO DEL INTERIOR Fernández y otro.—Página 7740 ;creío autorizando al Ministerio del Otra id. la id. del id. y su id, en el Otra id. al Comandante id. D. Luis ¡ ínicrior para organizar, por medio id. del Caho de Seguridad José Martínez dt Veíasco y un Tenien- i él Servicio Nacional de Turismo. -

Alaska Beyond Magazine

The Past is Present Standing atop a sandstone hill in Cabrillo National Monument on the Point Loma Peninsula, west of downtown San Diego, I breathe in salty ocean air. I watch frothy waves roaring onto shore, and look down at tide pool areas harboring creatures such as tan-and- white owl limpets, green sea anemones and pink nudi- branchs. Perhaps these same species were viewed by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542 when, as an explorer for Spain, he came ashore on the peninsula, making him the first person from a European ocean expedition to step onto what became the state of California. Cabrillo’s landing set the stage for additional Span- ish exploration in the 16th and 17th centuries, followed in the 18th century by Spanish settlement. When I gaze inland from Cabrillo National Monument, I can see a vast range of traditional Native Kumeyaay lands, in- cluding the hilly area above the San Diego River where, in 1769, an expedition from New Spain (Mexico), led by Franciscan priest Junípero Serra and military officer Gaspar de Portolá, founded a fort and mission. Their establishment of the settlement 250 years ago has been called the moment that modern San Diego was born. It also is believed to represent the first permanent European settlement in the part of North America that is now California. As San Diego commemorates the 250th anniversary of the Spanish settlement, this is an opportune time 122 ALASKA BEYOND APRIL 2019 THE 250TH ANNIVERSARY OF EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT IN SAN DIEGO IS A GREAT TIME TO EXPLORE SITES THAT HELP TELL THE STORY OF THE AREA’S DEVELOPMENT by MATTHEW J. -

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1

Islenos and Malaguenos of Louisiana Part 1 Louisiana Historical Background 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 1761 – 1763 •Spain sides with France in the now expanded Seven Years War •The Treaty of Fontainebleau was a secret agreement of 1762 in which France ceded Louisiana (New France) to Spain. •Spain acquires Louisiana Territory from France 1763 •No troops or officials for several years •The colonists in western Louisiana did not accept the transition, and expelled the first Spanish governor in the Rebellion of 1768. Alejandro O'Reilly suppressed the rebellion and formally raised the Spanish flag in 1769. Antonio de Ulloa Alejandro O'Reilly 1763 – 1770 1763 – 1770 •France’s secret treaty contained provisions to acquire the western Louisiana from Spain in the future. •Spain didn’t really have much interest since there wasn’t any precious metal compared to the rest of the South America and Louisiana was a financial burden to the French for so long. •British obtains all of Florida, including areas north of Lake Pontchartrain, Lake Maurepas and Bayou Manchac. •British built star-shaped sixgun fort, built in 1764, to guard the northern side of Bayou Manchac. •Bayou Manchac was an alternate route to Baton Rouge from the Gulf bypassing French controlled New Orleans. •After Britain acquired eastern Louisiana, by 1770, Spain became weary of the British encroaching upon it’s new territory west of the Mississippi. •Spain needed a way to populate it’s new territory and defend it. •Since Spain was allied with France, and because of the Treaty of Allegiance in 1778, Spain found itself allied with the Americans during their independence. -

Rebellion in Spanish Louisiana During the Ulloa, O

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The poisonous wine from Catalonia: rebellion in Spanish Louisiana during the Ulloa, O'Reilly, and Carondelet administrations Timothy Paul Achee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Achee, Timothy Paul, "The poisonous wine from Catalonia: rebellion in Spanish Louisiana during the Ulloa, O'Reilly, and Carondelet administrations" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 399. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POISONOUS WINE FROM CATALONIA: REBELLION IN SPANISH LOUISIANA DURING THE ULLOA, O’REILLY, AND CARONDELET ADMINISTRATIONS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of History By Timothy Paul Achee, Jr. B.A., Louisiana State University, 2006 B.A. (art history), Louisiana State University, 2006 MLIS, Louisiana State University, 2008 May, 2010 For my father- I wish you were here ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis could not have been written without the support and patience of several people. I would like to take a moment to acknowledge some of them. Dr. Paul Hoffman provided invaluable guidance, encouragement and advice. -

COURSE LEGEND L M T T G a N a a a a N H M a W Dr Ct H W a V 274 N R O E U Tol V I V O a P a a a D Ac E H If E Y I V V Ca E D D R E Ur St G Beadnell Way Armo a R F E

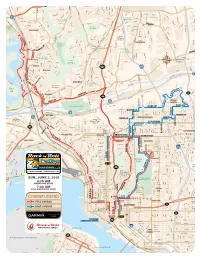

C a r d y a e Ca n n W n S o o in g n t r D i to D n S r n L c t o i u D e n c S n ate K n o r e g R a G i e l ow d l c g s A e C e id r v e w S v l e Co R e e f n mplex Dr d v a e a v l h B e l l ld t s A h o C J Triana S B a a A e t A e S J y d nt a s i a e t m v e gu e L r S h a s e e e R Ave b e t Lightwave d A A v L t z v a e M v D l A sa Ruffin Ct M j e n o r t SUN., JUNE 2, 2013 B r n e d n o Mt L e u a a M n r P b r D m s l a p l D re e a A y V i r r h r la tt r i C a t n Printwood Way i M e y r e d D D S C t r M v n a w I n C a d o C k Vickers St e 6:15 AM a o l l e Berwick Dr O r g c n t w m a e h i K i n u ir L i d r e i l a Engineer Rd J opi Pl d Cl a n H W r b c g a t i Olive Spectrum Center MARATHON STy ART m y e e Blvd r r e Ariane Dr a y o u o D u D l S A n L St Cardin Buckingham Dr s e a D h a y v s r a Grove R Soledad Rd P e n e R d r t P Mt Harris Dr d Opportunity Rd t W a Dr Castleton Dr t K r d V o e R b S i F a l a c 7:00 AM e l m Park e m e l w a Mt Gaywas Dr l P o a f l h a e D S l C o e o n HALF-MARATHON START t o t P r o r n u R n D p i i Te ta r ch Way o A s P B r Dagget St e alb B d v A MT oa t D o e v Mt Frissell Dr Arm rs 163 e u TIERRASANTA BLVD R e e s D h v v r n A A Etna r ser t t a our Av S y r B A AVE LBO C e i r e A r lla Dr r n o M b B i a J Q e e r Park C C L e h C o u S H a o te G M r Orleck St lga a t i C t r a t H n l t g B a p i S t E A S o COURSE LEGEND l M t t g a n a a a a n H a w M Dr Ct h w A v 274 n r o e u Tol v i v o a P A A a D ac e h if e y ica v v e D D r e ur St g Beadnell Way Armo -

Grinding Stone Reuse 1983

The Effects of Grinding Stone Reuse on the Archaeological Record in the Eastern Great Basin Author(s): STEVEN R. SIMMS Source: Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, Vol. 5, No. 1/2 (Summer and Winter 1983), pp. 98-102 Published by: Malki Museum, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825137 Accessed: 30-11-2015 18:41 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Malki Museum, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.123.24.42 on Mon, 30 Nov 2015 18:41:26 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Vol. 5, Nos. 1 and 2, pp. 98-102 (1983). The Effects of Grinding Stone on Reuse the Archaeological Record in the Eastern Great Basin STEVEN R. SIMMS are aware thatmany hunter-gatherer societies where the transpor ARCHAEOLOGISTSfactors change archaeological sites after tation of material culture is a limiting factor. they have been initially deposited. One kind Reuse can include the use of grinding stones of post-depositional phenomena that could from nearby, older sites or the caching of change the material record is the scavenging previously used grinding stones. -

Colonial Spanish Terms Compilation

COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS file:///C|/...20Grant%202013/Articles%20&%20Publications/Spanish%20Colonial%20Glossary/COLONIAL%20SPANISH%20TERMS.htm[5/15/2013 6:54:54 PM] COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES Second edition, 1998 Compiled and edited by: Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Navarro Wold Copyright, 1998 Published by: SHHAR PRESS, 1998 (Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research) P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 1-714-894-8161 Cover: Census Bookcover was provided by Ophelia Marquez . In 1791, and again in 1792, a census was ordered throughout the viceroyalty by Viceroy Conde de Revillagigedo. The actual returns came in during 1791 - 1794. PREFACE This pamphlet has been compiled in response to the need for a handy, lightweight dictionary of Colonial terms to use while reading documents. This is a supplement to the first edition with additional words and phrases included. Refer to pages 57 and 58 for the most commonly used phrases in baptismal, marriage, burial and testament documents. Acknowledgement Ophelia and Lillian want to record their gratitude to Nadine M. Vasquez for her encouraging suggestions and for sharing her expertise with us. Muy EstimadoS PrimoS, In your hands you hold the results of an exhaustive search and compilation of historical terms of Hispanic researchers. Sensing the need, Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Wold scanned hundreds of books and glossaries looking for the most correct interpretation of words, titles, and phrases which they encountered in their researching activities. Many times words had several meanings. -

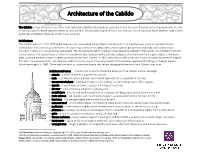

Architecture of the Cabildo

Architecture of the Cabildo The Cabildo in New Orleans is one of the most historically significant buildings in Louisiana. It was the seat of Spanish colonial government, the site of the Louisiana Purchase transfer ceremony, and home of the Louisiana Supreme Court. It is now part of the Louisiana State Museum. Learn more about the architectural features of this iconic building! Architecture The Cabildo was built 1794-1799 under Spanish rule. It was designed by Gilberto Guillemard in the classical style, which is modelled on the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome. This style was common for eighteenth-century Spanish government buildings and has been used throughout history to convey power and wealth. The wrought-iron balcony railings were created by Marcelino Hernandez, an immigrant from the Canary Islands. The Spanish coat of arms in the pediment was replaced with a patriotic sculpture of an American bald eagle in 1821, a few years after Louisiana became a state, sculpted by Italian artist Pietro Cardelli. In 1847, a third floor with a mansard roof and cupola replaced the original flat roof. This popular French roof style was added in part to match the planned scale of the Pontalba apartment buildings on Jackson Square, which were begun in 1849. These features form an impressive façade that reflect changing influences in New Orleans over time. Architectural terms1 – Use this list of terms to label the drawing of the Cabildo on the next page. • arcade – a series of arches supported by columns • arch – a curved structural element spanning -

Maize and Stone a Functional Analysis of the Manos and Metates of Santa Rita Corozal, Belize

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 Maize And Stone A Functional Analysis Of The Manos And Metates Of Santa Rita Corozal, Belize Lisa Glynns Duffy University of Central Florida Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Duffy, Lisa Glynns, "Maize And Stone A Functional Analysis Of The Manos And Metates Of Santa Rita Corozal, Belize" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1920. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1920 MAIZE AND STONE: A FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE MANOS AND METATES OF SANTA RITA COROZAL, BELIZE by LISA GLYNNS DUFFY B.A. University of South Florida, 1988 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2011 ABSTRACT The manos and metates of Santa Rita Corozal, Belize are analyzed to compare traditional maize-grinding types to the overall assemblage. A reciprocal, back-and-forth grinding motion is the most efficient way to process large amounts of maize. However, rotary movements are also associated with some ground stone implements. The number of flat and trough metates and two handed manos are compared to the rotary-motion basin and concave type metates and one-handed manos to determine predominance and distribution. -

Excavations at the Green Lizard Site, Pp. 69-77

Excavations at the Green Liza_rd Site . Edgar K. Huber and William D. Lipe Introduction than Sand Canyon Pueblo, or was abandoned before the end of occupation at the larger site, does comparison of he Green Lizard site (5MT3901) is a small, Pueblo III artifacts and ecofacts from the two sites provide evidence T habitation site located in the middle reaches of Sand that may help us understand the shift from a dispersed to Canyon, approximately 1 km down canyon from Sand an aggregated settlement pattern and/or the eventual aban Canyon Pueblo (Figure 1.3). In the summers of 1987 and donment of the Sand Canyon locality? 1988, intensive excavation was carried out in the western In planning for the Green Lizard excavations, we de half of the site. A kiva, an adjacent masonry· roomblock, cided to excavate a full kiva suite (kiva and associated and the floors of several jacal structures were excavated; surface rooms) to obtain a data set fully comparable to those the midden lying to the south of these features was sampled being produced by the intensive excavations of kiva suites with test pits (Figure 6~ 1). at Sand Canyon Pueblo (Bradley, this volume; see also The Green Lizard site Was first recorded by Craw Adams 1985a; Bradley 1986, 1987, 1988a, 1990; Kleidon Canyon Center researchers in 1984 (Adams 1985a). The and Bradley 1989). layout of the site is essentially two adjacent Prudden units (Prudden 1903, 1914, 1918). It consists of two kivas, Environmental Setting approximately 20 more or less contiguous, masonry-walled surface rooms, and an extensive and reJatively deep midden The Green Lizard site is located within Sand Canyon on a deposit located to the south of the structures (Figure 6.1).