Mapping Metro, 1955-1968: Urban, Suburban, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Council Agenda

CITY COUNCIL AGENDA COUNCIL MEETINGS WILL BE ONLINE Due to the COVID-19 precautions, the Council Meetings will be held online and is planned to be cablecast on Verizon 21, Comcast 71 and 996 and streamed to www.greenbeltmd.gov/municipaltv. Resident participation: Join By Phone: (301) 715-8592 Webinar ID: 842 3915 3080 Passcode: 736144 In advance, the hearing impaired is advised to use MD RELAY at 711 to submit your questions/comments or contact the City Clerk at (301) 474-8000 or email [email protected]. Monday, October 12, 2020 8:00 PM I. ORGANIZATION 1. Call to Order 2. Roll Call 3. Meditation and Pledge of Allegiance to the Flag 4. Consent Agenda - Approval of Staff Recommendations (Items on the Consent Agenda [marked by *] will be approved as recommended by staff, subject to removal from the Consent Agenda by Council.) 5. Approval of Agenda and Additions II. COMMUNICATIONS 1 6. Presentations 6a. Co-op Month Proclamation Suggested Action: Every October is a chance to celebrate cooperatives, uniquely-local organizations. The theme for this year’s National Co-Op Month is “Co-Ops: By the Community, For the Community”. Members from more than 40,000 cooperatives nationwide will celebrate the advantages of cooperative membership and recognize the benefits and values cooperatives bring to their members and communities. Representatives from Greenbelt’s seven cooperatives have been invited to attend tonight’s meeting to receive a proclamation announcing the City’s support and recognition of cooperative businesses and organizations during this month. version 2 CoopMonth 19 proc.pdf 6b. Maryland Economic Development Week Suggested Action: October 19th – 23rd is Maryland’s Economic Development Week. -

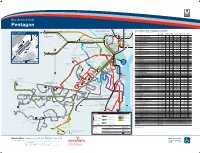

Metrobus Routes

Bus Service from Pentagon - Dupont Shaw Sunset Hills Rd POTOMAC RIVER Circle Howard U Wiehle Ave BUS SERVICE AND BOARDING LOCATIONS 599 267 WASHINGTON 599 The table shows approximate minutes between buses; check schedules for full details Farragut Mt Vernon BUS BOARDING MAP Wiehle- Foggy Bottom- Farragut North McPherson Union Reston East GWU West Square Square Station BOARD AT MONDAY TO FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Spring Hill ROUTE DESTINATION BUS BAY AM RUSH MIDDAY PM RUSH EVENING DAY EVENING DAY EVENING 110 Metro Gallery Judiciary Greensboro LINCOLNIA-NORTH FAIRLINGTON LINE The Pentagon 7Y H St 16E Center Place Square RESTON 66 7A Lincolnia via Quantrell Ave U5 40-60 40 -- 15-55 60 30-60 45 45 J J e e 698 f f f f e Tysons Corner 599 7F Lincolnia via N Hampton Dr, Chambliss St U5 60 40 -- 60 60 -- -- -- e r r s 18th St s Washington Blvd 698 16C o o n 14th St 12th St E St n Rosslyn 7Y Farragut Square U9 8-24 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 42 m D U13 D Penn. Ave a 66 a McLean 22A Ballston-MU Virginia Square-GMU Clarendon Court House v Wilson v i 7A 7Y Southern Towers U5 -- -- 10-20 -- -- -- -- -- i s Blvd U12 s 22C H H Federal Archives w 7th St w U11 y Triangle PARK CENTER-PENTAGON LINE y Highland St 599 U10 L11 East Falls Church Wilson Blvd 698 Constitution Ave 7C Park Center via Walter Reed U5 -- -- 20-35 -- -- -- -- -- U8 St Randolph 42 Washington Blvd t 16E 16C L10 S Glebe Theodore Roosevelt U7 U9 7P Park Center U5 20-30 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- s Rd Memorial Bridge d The Mall L9 a Federal U6 E Center SW LINCOLNIA-PENTAGON LINE L8 S Smithsonian Independence -

Bus Service from Pentagon

Bus Service from Pentagon - Dupont Shaw Sunset Hills Rd POTOMAC RIVER Circle Howard U schematic map Wiehle Ave BUS SERVICE AND BOARDING LOCATIONS LEGEND not to scale 267 WASHINGTON 599 The table shows approximate minutes between buses; check schedules for full details Farragut Mt Vernon Rail Lines Metrobus Routes 599 Wiehle- Foggy Bottom- Farragut North McPherson Union Square MONDAY TO FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Reston East GWU West Square NY 7Y Station BOARD AT Spring Hill Ave 16A Metrobus Major Route K St ROUTE DESTINATION BUS BAY AM PEAK MIDDAY PM PEAK EVENING DAY EVENING DAY EVENING 10th St 13Y Metrorail Frequent, seven-day service on the core route. On branches, service levels vary. Metro Gallery Judiciary LINCOLNIA-NORTH FAIRLINGTON LINE Station and Line Greensboro 66 Center Place Square 9A Metrobus Local Route RESTON 7A Lincolnia via Quantrell Ave U5 30-50 40 -- 15-40 60 30-60 40 60 Less frequent service, with some evening North St Capitol Metrorail 599 7F Lincolnia via N Hampton Dr, Chambliss St U5 60 40 -- 60 60 -- -- -- and weekend service available. Tysons Corner 7Y Under Construction Washington Blvd 18th St 14th St 7Y New York Ave & 9th St NW U9 7-25 -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 18P Metrobus Commuter Route 42 Rosslyn E St Peak-hour service linking residential areas McLean East Falls Church 22A Ballston-MU Virginia Square-GMU Clarendon Court House 16X 7A 7Y Southern Towers U5 -- -- 5-15 -- -- -- -- -- to rail stations and employment centers. 22C St 23rd Federal LINCOLNIA-PARK CENTER LINE Commuter 16X MetroExtra Route Triangle Archives Rail Station Limited stops for a faster ride. -

10B-FY2020-Budget-Adoption-FINALIZED.Pdf

Report by Finance and Capital Committee (B) 03-28-2019 Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Board Action/Information Summary MEAD Number: Resolution: Action Information 202068 Yes No TITLE: Adopt FY2020 Operating Budget and FY2020-2025 CIP PRESENTATION SUMMARY: Staff will review feedback received from the public and equity analysis on the FY2020 Proposed Budget and request approval of the Public Outreach and Input Report, FY2020 Operating Budget and FY2020-2025 Capital Improvement Program (CIP). PURPOSE: The purpose of this item is to seek Board acceptance and approval of the Public Outreach and Input Report and Title VI equity analysis, and the FY2020 Operating Budget and FY2020-2025 CIP. DESCRIPTION: Budget Priorities: Keeping Metro Safe, Reliable and Affordable The budget is built upon the General Manager/CEO's Keeping Metro Safe, Reliable and Affordable (KMSRA) strategic plan. Metro is making major progress to achieve the goals of this plan by ramping up to average capital investment of $1.5 billion annually, establishing a dedicated capital trust fund exclusive to capital investment, and limiting jurisdictional annual capital funding growth to three percent. Metro continues to encourage the U.S. Congress to reauthorize the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (PRIIA) beyond FY2020, which provides $150 million in annual federal funds matched by $150 million from the District of Columbia, State of Maryland, and Commonwealth of Virginia. In order to establish a sustainable operating model, Metro is limiting jurisdictional operating subsidy growth to three percent and deploying innovative competitive contracting. The items on the KMSRA agenda that remain to be completed include restructuring retirement benefits and creating a Rainy Day Fund. -

Gmf-Icsp-Wsw-2012

Agenda ICSP/GMF Meeting 9 am - 12pm October 9, 2011 Newseum, Knight Conference Center 555 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, 6th Street Entrance, The Freedom Forum Entrance, Washington, DC 20001 Co Chairs: Mary Saunders NIST, ICSP and Mary McKiel, EPA, GMF ICSP Closed Session – Federal Government Only 9:05-10:15 ICSP Closed Door Meeting – see ICSP meeting agenda for call in information ICSP/GMF Joint Session – Open to All Teleconference Call In: 1-866-469-3239 or 1-650-429-3300 Host access code (Scott): 25558273 Attendee access code: 25515125 10:30 Welcome- Co-Chairs: Mary Saunders NIST, ICSP and Mary McKiel, EPA, GMF 10:35 Remarks – Joe Bhatia, ANSI 10:40 Self introductions – All 10:45 Incorporation by Reference issues before PHMSA – Tim Klein, DOT 10:55 Discussion of Standards Incorporated by Reference Database – Fran Schrotter, ANSI 11:15 Discussion of NAESB ‘Green Button’ smart meter standard success story- Dave Wollman, NIST 11:35 ISO General Assembly Update – Mary McKiel, EPA 11:45 Current legislative activities of potential interest to the standardization community – Scott Cooper, ANSI 11:50-noon Other Business, Next Meeting Adjourn Directions to the Newseum Newseum 555 Pennsylvania Ave, NW 6th Street Entrance Washington, DC 20001 Metro Accessible Archives/Navy Memorial-Penn Quarter Station • • Take the Green or Yellow Line to the Archives/Navy Memorial-Penn Quarter Metro Station. Exit the station, turn left and walk toward Pennsylvania Avenue. Turn left onto Pennsylvania Avenue, walk toward the Capitol and cross Seventh Street. Walk one block to the Newseum, located at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and Sixth Street. -

Elegant Report

Pennsylvania State Transportation Advisory Committee PENNSYLVANIA STATEWIDE PASSENGER RAIL NEEDS ASSESSMENT TECHNICAL REPORT TRANSPORTATION ADVISORY COMMITTEE DECEMBER 2001 Pennsylvania State Transportation Advisory Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements...................................................................................................................................................4 1.0 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................5 1.1 Study Background........................................................................................................................................5 1.2 Study Purpose...............................................................................................................................................5 1.3 Corridors Identified .....................................................................................................................................6 2.0 STUDY METHODOLOGY ...........................................................................................................7 3.0 BACKGROUND RESEARCH ON CANDIDATE CORRIDORS .................................................14 3.1 Existing Intercity Rail Service...................................................................................................................14 3.1.1 Keystone Corridor ................................................................................................................................14 -

Cotton Annex Redevelopment

Comprehensive Transportation Review Cotton Annex Redevelopment Washington, DC February 8, 2021 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia CASE NO.20-34 EXHIBIT NO.9A Prepared by: 1140 Connecticut Ave NW 3914 Centreville Road 15125 Washington Street 225 Reinekers Lane Suite 600 Suite 330 Suite 212 Suite 750 Washington, DC 20036 Chantilly, VA 20171 Haymarket, VA 20169 Alexandria, VA 22314 T 202.296.8625 T 703.787.9595 T 571.248.0992 T 202.296.8625 www.goroveslade.com This document, together with the concepts and designs presented herein, as an instrument of services, is intended for the specific purpose and client for which it was prepared. Reuse of and improper reliance on this document without written authorization by Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc., shall be without liability to Gorove/Slade Associates, Inc. Cotton Annex Redevelopment – Comprehensive Transportation Review (CTR) i February 8, 2021 CONTENTS Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Purpose of Study .................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Project Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Proposed Judiciary Square Historic District

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE HISTORIC PRESERVATION REVIEW BOARD APPLICATION FOR HISTORIC LANDMARK OR HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGNATION New Designation _X_ Amendment of a previous designation __ Please summarize any amendment(s) Property name Judiciary Square Historic District If any part of the interior is being nominated, it must be specifically identified and described in the narrative statements. Address Roughly bounded by Constitution and Pennsylvania Avenues, N.W. and C Street, N.W. to the south, 6th Street to the west, G Street to the north, and 3rd and 4th Streets N.W to the east. See Boundary Description section for details. Square and lot number(s) Various Affected Advisory Neighborhood Commission 2C Date of construction 1791-1968 Date of major alteration(s) Various Architect(s) Pierre Charles L’Enfant, George Hadield, Montgomery C. Meigs, Elliott Woods, Nathan C. Wyeth, Gilbert S. Underwood, Louis Justement Architectural style(s) Various Original use Various Property owner Various Legal address of property owner Various NAME OF APPLICANT(S) DC Preservation League If the applicant is an organization, it must submit evidence that among its purposes is the promotion of historic preservation in the District of Columbia. A copy of its charter, articles of incorporation, or by-laws, setting forth such purpose, will satisfy this requirement. Address/Telephone of applicant(s) 1221 Connecticut Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 Name and title of authorized representative Rebecca Miller, Executive Director Signature of representative _______ _____ Date ____10/25/2018______ Name and telephone of author of application DC Preservation League, 202.783.5144 Office of Planning, 801 North Capitol Street, NE, Suite 3000, Washington, D.C. -

Falls Church Mclean Washington Alexandria

Canal Rd NW Wisconsin Ave NW 924 926 Leesburg Pike Capital LANGLEY Beltway Dolley Madison Blvd George Washington Pkwy 721 15K 495 15L GEORGETOWN Dranesville Rd BEVERLY RD 15K Lewinsville Rd N Glebe Rd MCLEAN 53B Military Rd George Washington Pkwy 724 53 554 Old Glebe POTOMAC RIVER See Central DC inset 558 Rd on reverse side Spring Hill Rd Williamsburg Blvd Reston Pkwy M ST NW Lake Newport Rd Farm Farm Credit Dr Lewinsville Rd 38B Leesburg Pike Lorcom Ln 62 Lorcom Ln Fairfax County Pkwy Center Harbor Rd Credit DOLLEY MADISON BLVD RB4 Admin OLD DOMINION DR 15L RB4 556 Jones Branch Dr 5A 15L non-stop 5A to Rosslyn HERNDON Wiehle Ave 574 424 494 495 480 23A Walnut Branch Rd 432 Tysons 3Y 21st St Baron Cameron Ave 23T 924 480 424 432 Westpark 423 599 WASHINGTON Bennington RB4 556 552 Spout Run Pkwy Woods Rd Baron Cameron 558 599 494 495 423 Transit Station Westpark Dr WHITTIER AVE Yorktown 5A non-stop to/from Park & Ride 558 574 724 Herndon Monroe 926 RB5 RB5 Blvd LEE HWY Spout Run Pkwy Dr Run Park Sully Rd 574 724 61 Foggy Bottom-GWU Park Ave 574 52 LEE HWY 55 Park & Ride LEE HWY Loudoun County RB5 Baron Cameron Ave 401 423 McLean CHAIN BRIDGE RD Stevenage Rd 5A KEY BRIDGE Transit offers Rd Village Ring Rd Tysons Blvd 62 53 574 267 402 International 424 721 Tyco Rd N GLEBE RD commuter service Kmart Dr Utah St Quincy St 55 574 494 Little Falls 62 Scott St 15K from Leesburg, Herndon Pkwy 937 23A 2T Galleria Dr Rd 61 Veitch St Veitch Lake Fairfax Dr Key 552 495 Sycamore St Patrick 15L Ashburn and other ANDERSON RD 23T 3Y 15L Monroe St Grace -

Reagan National

Monday, October 11th Honor Guard Teams / Motors / Support Staff Arrive Tuesday, October 12th Early Arrival Day (Reagan National Airport) for Survivors, 9 AM to 6 PM Colorado Survivor / Peace Officer Reception, 5 PM to 8 PM * * Wednesday, October 13th Official Arrival Day (Reagan National Airport) for Survivors, 9 AM to 6 PM C.O.P.S. 3rd Annual Blue Honor Gala, 6:30 PM Thursday, October 14th C.O.P.S. Blue Family Brunch at Hilton Alexandria Mark Center ***Colorado Peace Officer Group Photo 7th St NW & Indiana Ave NW, 5:15 PM*** NLEOMF Candlelight Vigil on the National Mall, 6 PM Friday, October 15th C.O.P.S. Survivors’ Conference & Kids Programs C.O.P.S. Picnic on the Patio Steve Young Honor Guard / Pipe Band Competition CANCELLED 27th Annual Emerald Society Memorial March, 5 PM Saturday, October 16th National Peace Officers’ Memorial Service (West Front Lawn US Capitol) 12 PM Stand Watch for the Fallen, 2 PM to Midnight at Memorial Sunday, October 17th 30th Anniversary Commemoration at Memorial, 9 AM to 10:30 AM Produced by Danny Veith - Colorado Fallen Hero Foundation - 720.373.6512 - [email protected] Page 1 of 18 Never before has this annual guide been distributed just 8-weeks before Police Week. This guide was delayed to insure Police Week events were not cancelled (as occurred in May of 2019), postponed (as occurred last May), all while monitoring District of Columbia health orders (for example, an order by the Mayor’s Office on July 29, 2021 to resume indoor mask use). Because of the pandemic, this is the first time National Police Week will occur outside the week encompassing May 15th. -

National Gallery

West Building East Building Main Floor 1 – 13 13th- to 16th-Century Italian 35 – 35A, 15th- to 16th-Century 53 – 56 18th- and Early 19th-Century Tower 2 Modern and Paintings and Sculptures 38 – 41A Netherlandish and German French Paintings and Sculptures Contemporary Art Paintings and Sculptures 17 – 28 16th-Century Italian, French, and 57 – 59, 61 British Paintings and Sculptures Roof Special Exhibitions Terrace Spanish Paintings, Sculptures, 42 – 51 17th-Century Dutch and Flemish 60 – 60B, American Paintings and Sculptures Roof Terrace and Decorative Arts Paintings 62 – 71 Tower 3 Tower 2 Tower 1 Public Space 29 – 34, 17th- to 18th-Century Italian, 52 18th- and 19th-Century Spanish 80 – 93 19th-Century French Paintings 36 – 37 Spanish, and French Paintings and French Paintings Closed to the Public 72 – 79 Special Exhibitions Roof Terrace Tower 3 Tower 1 Tower Level 19 18 17 20 21 24 12 23 13 25 22 Sculpture Garden 26 27 11 28 10 19 9 18 6 Tower 2 17 5 3 Lobby A 20 8 2 31 24 West 21 7 23 Garden 12 4 29 13 80 32 25 Court22 Lobby B 1 79 30 11 91 Sculpture Garden 26 27 10 81 78 33 28 45 9 92 90 87 82 37 46 6 88 86 75 Tower 2 38 5 93 76 43 48 3 83 77 34 Lobby A 44 8 51 50C 2 89 31 36 West 47 7 85 74 Tower 1 39 Garden 49 4 Rotunda 84 73 Tower 3 35 29 42 50B 80 32 35A Court Lobby B 50 1 79 30 40 50A 91 78 41 52 92 90 87 Lobby C East81 82 33 41A 45 Information Founders 56 75 72 37 46 Room 88 86 Garden 76 38 48 Room 53 93 57 77 34 43 89 58 83Court Lobby D Terrace Café 36 44 47 51 50C 54 74 Tower 1 39 55 85 73 Tower 3 Upper Level 35 42 49 50B -

Columbia Pike Transit Service Analysis

COLUMBIA PIKE AM PEAK S Arlington TDP .G S S . G S eo C TRAFFIC S e . o . S C o r Level of Service (LOS) u D . o r g Di g u S r i e S t e r nw . n . t h M G h w M G ! A (< 10s delay) o o l i as l e i u a u d e d b se d s s on b d Major Arterial with 25,000 daily vehicles between the County line and e i o e Rd e e i ! B (10-15s delay) Rd R n D e «¬ D 27 S R d «¬27 r ! t S . d t. r . S ! . Washington Boulevard ! . C (15-25s delay) ! !! !! !!! ! ! . ! ! ! ! J !! S o ! ! S y S . c !!W !! !!! ! ! S ! ! J . ! !! e !! o . Je ! ! ! a D (25-35s delay) F . S r y o l t S f t c f ur M . e S D e . er . Fo r J d S Overall traffic operations do not show high levels of delay or congestion ! E (35-50s delay) e s Re on S i e t f l e . f ur e e er R d R u t M D s n ! . F (> 50s delay) er o i r during peak travel periods l D . t e R l 395 395 n r ¦¨§ ¦¨§ . a S W u . t n . S Dr Intersections with the greatest delay for vehicles and buses are: . PM PEAK S Arlington TDP .G S S . G S eo C S e .