Evaluating the Early Impact of Integrated Children's Services Round 1 Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portsmouth City Council Market Position Statement

` Portsmouth City Council Market Position Statement December 2015 www.portsmouth.gov.uk 1 Portsmouth Market Position Statement Contents Executive summary .............................................................................................................................. 4 1. Our vision ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Background ................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 National context ................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Local context ................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Portsmouth adult social care budget ................................................................................................ 8 2.4 Portsmouth demography ................................................................................................................. 9 2.5 Portsmouth City Council policies and strategies ............................................................................ 10 3. Emerging areas of work ............................................................................................................... 11 3.1 Better Care Fund .......................................................................................................................... -

Portsmouth Report October 2019

Portsmouth Report October 2019 Max Thorne, Narup Chana, Thomas Domballe, Kat Stenson, Laura Harris, Bryony Hutchinson and Vikkie Ware MRP GROUP 11-15 High1 Street, Marlow, SL7 1AU Contents Executive Summary 3 Portsmouth Profile 3 Developments 4 Economic Overview 6 Transport 7 Leisure Overview 8 Current Local Hospitality Market 9 Annual Occupancy, ADR and Room Yield Figures 10 The Team 11 2 Executive Summary Portsmouth has long been known for its maritime heritage and association to the Royal Navy. Investment is being put into the city’s internet speed, to make it one of 42 Gigabit cities in the UK. As well as this, Portsmouth City Council are working collaboratively to improve and maintain a healthy air quality, in order to make it a healthier and cleaner city. Portsmouth Profile Portsmouth is a port city in South Hampshire, and home to the majority of the UK naval fleet. Due to its location it has been an established maritime centre for many years with a heritage in shipbuilding. This has evolved over time along with new innovations, attracting new sectors to support the maritime and defence industries. As a consequence of it being a centre for employment, the population is approximately 215k with a population density exceeding London (Portsmouth City Council, 2019). This is bolstered by the University of Portsmouth who have over 24k students (Portsmouth City Council, 2019). With such a large number of students, companies in Portsmouth have a talented pool of graduates in the pipeline with the opportunity for industrial placements. Source: Invest in Portsmouth 3 Economic Overview In 2018 it was predicted that Portsmouth would be in the top ten cities for the fastest economic growth and is currently ranked in the top 20 cities for GVA. -

Regeneration, Culture and Environment Overview & Scrutiny Committee

REGENERATION, CULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT OVERVIEW & SCRUTINY COMMITTEE 15 AUGUST 2019 ATTENDANCE OF THE PORTFOLIO HOLDER FOR FRONT LINE SERVICES Report from: Portfolio Holder for Front Line Service, Councillor Filmer Summary This report sets out progress made within the areas covered by the Portfolio Holder for Front Line Services which fall within the remit of this Committee. 1 BACKGROUND 1.1 The areas within the terms of reference of this Overview and Scrutiny Committee covered by the Portfolio Holder for Front Line Services are: Highways Street Lighting Parking Public Transport Traffic Management Transport Strategy Travel Safety Waste Collection/Recycling/Waste Disposal and Street Cleaning 1.2 Achievements for 2018/19 are detailed by service area below. 2 HIGHWAYS AND STREET LIGHTING 2.1.1 Highway Infrastructure Contract Performance 2.1.1 The Highways Infrastructure Contract (HIC) commenced 1 August 2017 and is a five year contract with options to extend subject to performance for a further five years. The HIC covers both Highway and Street Lighting Maintenance and also includes provision for Highway Construction Projects, Structures and Professional Services and is provided by Volker Highways. 2.1.2 Contract Performance 2.1.2.1 Delivered to programme and budget the planned resurfacing programme for carriageway and footways. The carriageway programme for 2018- 2019 was composed of 9 schemes totalling 5,120 linear metres and the footway programme was composed of 7 schemes totalling 2,670 linear metres. Schemes are selected on condition survey data and prioritised according to the available budget being principally funding through the annual Local Transport Plan allocation for Highway Maintenance from the Department of Transport. -

Choosing a Nursery/ School/College

SENDIASS Training for Parents & Carers of children with Special Educational Needs (0-25) Welcome Choosing a nursery/ school/ college for your child with SEN ( Special Educational Needs) Your Trainers: Hannah Pinchin and Hayley Legg HOUSE KEEPING • Microphones on mute please • Feel free to add comments and questions to the chat box and we will email you a summary sheet with the answers on after the talk • PowerPoint will be shared after the training – sit back and relax! SENDIASS (Special Educational Needs and Disability Information Advice and Support Service) Who are we? SEND Information Advice Support A service for those Providing factual Providing impartial Providing living or working information found in advice on what confidential with ages 0-25yrs SEND Law and steps to take in the individualised with Special practices as well as areas of Education, support to empower Educational Needs local knowledge and Health and Social those who seek our and Disabilities signposting Care assistance TYPES OF EDUCATION MAINTAINED INDEPENDENT Educational institutions Educational institutions controlled and funded independent of local (maintained) by local authorities / secretary of authorities state MAINSTREAM SPECIALIST RESOURCE BASE A mainstream school is a A special school is a school Resource bases provide school which is not a which is “specially targeted specialist support special school and is either organised to make special but are not separate a maintained school or an educational provision for schools or institutions. Academy (section 83 CAFA pupils with SEN” (section They are units within a 2014). 337 of the Education Act mainstream school. 1996). How to make a short list List your ideal school (involve the child/YP if possible) 1. -

City Council Meeting Agenda Request Please Put This Under My Name

CITY COUNCIL MEETING MUNICIPAL COMPLEX, EILEEN DONDERO FOLEY COUNCIL CHAMBERS, PORTSMOUTH, NH DATE: MONDAY, AUGUST 2, 2021 TIME: 6:30PM Members of the public also have the option to join the meeting over Zoom, a unique meeting ID and password will be provided once you register. To register, click on the link below or copy and paste this into your web browser: https://us06web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_fDmfDEg1RheL9Asv-5jNZA 6:30PM – ANTICIPATED NON-PUBLIC SESSIONS: 1. PARAEDUCATORS ASSOCIATION TENTATIVE AGREEMENT – COLLECTIVE BARGAINING – RSA 91-A:3, II (a) 2. FOOD SERVICE TENTATIVE AGREEMENT – COLLECTIVE BARGAINING – RSA 91-A:3, II (a) AGENDA I. WORK SESSION – THERE IS NO WORK SESSION THIS EVENING II. PUBLIC DIALOGUE SESSION [when applicable – every other regularly scheduled meeting] – N/A III. CALL TO ORDER [7:00 p.m. or thereafter] IV. ROLL CALL V. INVOCATION VI. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE VII. ACCEPTANCE OF MINUTES – MAY 4, 2021 & JULY 12, 2021 (Sample motion – move to accept and approve the minutes of the May 4, 2021 and July 12, 2021 City Council meetings) VIII. RECOGNITIONS AND VOLUNTEER COMMITTEE REPORTS IX. PUBLIC COMMENT SESSION – (Via Zoom) X. PUBLIC DIALOGUE SUMMARY [when applicable] – N/A XI. PUBLIC HEARINGS AND VOTE ON ORDINANCE AND/OR RESOLUTIONS Public Hearings of Ordinance and Resolutions with Adoption: A. ORDINANCE AMENDING CHAPTER 1, ARTICLE IV – COMMISSIONS AND AUTHORITIES, SECTION 1.414 AUDIT COMMITTEE (Continued from the July 12, 2021 City Council meeting) PRESENTATION CITY COUNCIL QUESTIONS PUBLIC HEARING SPEAKERS ADDITIONAL COUNCILOR QUESTIONS AND DELIBERATIONS (Sample motion – move to continue the public hearing and the second reading at the August 23, 2021 City Council meeting) B. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Cabinet Member for Traffic

Public Document Pack NOTICE OF MEETING CABINET MEMBER FOR TRAFFIC & TRANSPORTATION THURSDAY, 2 APRIL 2020 AT 2.30 PM THE EXECUTIVE MEETING ROOM - THIRD FLOOR, THE GUILDHALL Telephone enquiries to Anna Martyn - Tel 023 9283 4870 Email: [email protected] If any member of the public wishing to attend the meeting has access requirements, please notify the contact named above. CABINET MEMBER FOR TRAFFIC & TRANSPORTATION Councillor Lynne Stagg Group Spokespersons Councillor Graham Heaney Councillor Simon Bosher (NB This agenda should be retained for future reference with the minutes of this meeting). Please note that the agenda, minutes and non-exempt reports are available to view online on the Portsmouth City Council website: www.portsmouth.gov.uk Deputations by members of the public may be made on any item where a decision is going to be taken. The request should be made in writing to the contact officer (above) by 12 noon of the working day before the meeting, and must include the purpose of the deputation (for example, for or against the recommendations). Email requests are accepted. A G E N D A 1 Apologies 2 Declarations of Members' Interests 3 LTP Implementation Plan 2020-2021 (Pages 5 - 24) Purpose The purpose of this report is to seek approval for the Local Transport Plan 3 (LTP 3) Implementation Plan 2020/21. An allocation of £835,000 was agreed for the 2020/21 LTP3 Implementation Plan by Full Council on 11 February 2020 as part of the council's 2020/21 Capital Programme. This report details the proposed programme of schemes to be carried out. -

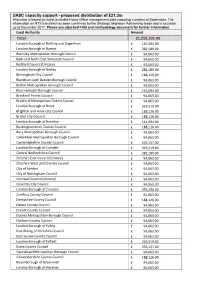

UASC Capacity Support - Proposed Distribution of £21.3M Allocation Is Based on Latest Available Home Office Management Data Capturing Numbers at September

UASC capacity support - proposed distribution of £21.3m Allocation is based on latest available Home Office management data capturing numbers at September. The information on NTS transfers has been confirmed by the Strategic Migration Partnership leads and is accurate up to December 2017. Please see attached FAQ and methodology document for further information. Local Authority Amount Total 21,258,203.00 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham £ 141,094.00 London Borough of Barnet £ 282,189.00 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bath and North East Somerset Council £ 94,063.00 Bedford Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Bexley £ 282,189.00 Birmingham City Council £ 188,126.00 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bournemouth Borough Council £ 141,094.00 Bracknell Forest Council £ 94,063.00 Bradford Metropolitan District Council £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Brent £ 329,219.00 Brighton and Hove City Council £ 188,126.00 Bristol City Council £ 188,126.00 London Borough of Bromley £ 141,094.00 Buckinghamshire County Council £ 188,126.00 Bury Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Cambridgeshire County Council £ 235,157.00 London Borough of Camden £ 329,219.00 Central Bedfordshire Council £ 282,189.00 Cheshire East Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Cheshire West and Chester Council £ 94,063.00 City of London £ 94,063.00 City of Nottingham Council £ 94,063.00 Cornwall Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Coventry City -

Tender for the Provision of Independent Fostering Agency Services

TENDER FOR THE PROVISION OF INDEPENDENT FOSTERING AGENCY SERVICES SOUTHAMPTON CITY COUNCIL (“The Council”) invites expressions of interest from suitably experienced firms/organisations for the provision of Independent Fostering Agency services. Southampton City Council are procuring these services for themselves and also for and on behalf of Bracknell Forest Council, Hampshire County Council, Oxfordshire County Council, Portsmouth City Council, Reading Borough Council, Slough Borough Council, Surrey County Council, West Berkshire Council, Windsor and Maidenhead Council and Wokingham Borough Council. The services will be provided through an Approved Provider List, Framework contract and Block contracts. The Approved Provider List will consist of all those providers that meet the council’s pre-determined criteria and accept the council’s contract conditions. Providers will be listed against a Lot or any combination of Lots from those listed below. The Framework Arrangement will contain multiple providers, divided into Lots. Placements through the Framework Arrangement will be made through a call-off process as set out in the framework agreement. Block contracts may also contain multiple providers, divided into Lots. Providers who wish to tender for the Framework and/or Block contracts will only be selected from those that have met the criteria for placement on the Approved Provider List and additional requirements detailed in the Instructions to Applicants. Providers will enter into an agreement for placement onto the Approved Provider List. Providers who are selected for inclusion on the Framework contract will enter into an agreement with the lead council (Southampton City Council), those Providers who are selected to provide services under a Block arrangement will enter into a services contract with those Councils (referred to above) which wish to have block arrangements. -

Appendix D STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL

Appendix D West Berkshire Council Senior Management Review STRICTLY CONFIDENTIAL Prepared for: Nick Carter Chief Executive West Berkshire Council Market Street Newbury RG14 5LD Prepared by: Jennifer McNeill Chartered Fellow CIPD; MA; BEd The Guildhall, High Street Regional Director Winchester, Hampshire, SO23 9GH South East Employers Telephone: 01962 840664 1 e-mail: [email protected] Website: www.seemp.co.uk 29 October 2018 (revised) 2 1. Context and purpose of review 1.1 West Berkshire Council (WBC) is aware that, given the higher age profile of senior managers (many are approaching 60 years of age), a number may retire soon (likely within 2-5 years). Therefore, as part of its workforce and succession planning process, the council seeks to commence early discussions about the current structure and the potential for realignment to meet future service demands and challenges, including scarcer resources and increasing competition in certain areas. 1.2 Workforce planning provides the means to review and redefine the senior manager structure to meet emerging demands and challenges in the medium to longer term. Early consideration can be given to the future shape and structure of the senior management team to meet changing service demands prior to vacancies starting to appear. 1.3 The development of a ‘blue-print’ to take the structure forward will inform decision- making for either a planned process of revising the structure, or to manage vacancies individually as they start to arise. 1.4 The council needs to be able to respond to any skills shortage areas or particular recruitment or retention difficulties. Is the council positioned to attract high level, or difficult to recruit to, skills to fill senior level vacancies when they arise in the short and medium term? 1.5 A planned approach will minimise disruption to service provision in those areas if the situation arises. -

Southampton and Portsmouth City Deal

Southampton and Portsmouth City Deal Executive Summary The Southampton and Portsmouth City Deal will maximise the economic strengths of these two coastal cities and the wider Solent area, by supporting further growth in the area‟s maritime, marine and advanced manufacturing sectors. Across Southampton, Portsmouth and the Solent, the marine and maritime sector already accounts for over 20% of gross value added and provides 40,000 jobs locally. Over the next 12 years this sector is expected to grow by 5%, driven in part by key assets such as the Port of Southampton, Portsmouth Naval Base; and the Solent Marine Cluster – which includes Lloyds Register and the Southampton Marine and Maritime Institute. Advanced manufacturing is also an area of strength, growing during the recent recession and creating almost 5,000 new jobs. The flagship proposal for this City Deal will support further growth in these sectors by unlocking two high- profile sites within Southampton and Portsmouth – one of which involves Ministry of Defence owned land. These sites, once developed, will provide: new employment space; new housing; and lever in significant amounts of new private sector investment into the economy. To complement this, the City Deal will also implement programmes to: align skills provision to employer needs; tackle long term unemployment and youth unemployment; and enable small and medium enterprises to grow through the provision of effective business support. Over its lifetime the Solent Local Enterprise Partnership predict the City Deal will deliver: Over 4,700 permanent new jobs particularly focussed in marine, maritime and advanced manufacturing sectors. Over 13,000 construction jobs. -

The Portsmouth Plan

The Portsmouth Plan Portsmouth's Core Strategy www.portsmouth.gov.uk 1 i A spatial plan for Portsmouth The Portsmouth Plan (Portsmouth’s Core Strategy) Adopted 24 January 2012 John Slater BA (Hons), DMS, MRTPI Head of Planning Services Portsmouth City Council Guildhall Square Portsmouth PO1 2AU ii iii Contents INTRODUCTION Introduction & overview ........................................................................................................ 2 A profile of Portsmouth - context & challenges .................................................................... 6 THE STRATEGY Vision & objectives ............................................................................................................. 12 A Spatial Strategy for Portsmouth ...................................................................................... 19 CORE POLICIES Tipner................................................................................................................................. 28 Port Solent and Horsea Island ........................................................................................... 37 Portsmouth city centre ....................................................................................................... 46 Lakeside Business Park..................................................................................................... 56 Somerstown and North Southsea ...................................................................................... 59 Fratton Park & the south side of Rodney Road ................................................................. -

List of Councils in England by Type

List of councils in England by type There are a total of 343 councils in England: • Metropolitan districts (36) • London boroughs (32) plus the City of London • Unitary authorities (55) plus the Isles of Scilly • County councils (26) • District councils (192) Metropolitan districts (36) 1. Barnsley Borough Council 19. Rochdale Borough Council 2. Birmingham City Council 20. Rotherham Borough Council 3. Bolton Borough Council 21. South Tyneside Borough Council 4. Bradford City Council 22. Salford City Council 5. Bury Borough Council 23. Sandwell Borough Council 6. Calderdale Borough Council 24. Sefton Borough Council 7. Coventry City Council 25. Sheffield City Council 8. Doncaster Borough Council 26. Solihull Borough Council 9. Dudley Borough Council 27. St Helens Borough Council 10. Gateshead Borough Council 28. Stockport Borough Council 11. Kirklees Borough Council 29. Sunderland City Council 12. Knowsley Borough Council 30. Tameside Borough Council 13. Leeds City Council 31. Trafford Borough Council 14. Liverpool City Council 32. Wakefield City Council 15. Manchester City Council 33. Walsall Borough Council 16. North Tyneside Borough Council 34. Wigan Borough Council 17. Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 35. Wirral Borough Council 18. Oldham Borough Council 36. Wolverhampton City Council London boroughs (32) 1. Barking and Dagenham 17. Hounslow 2. Barnet 18. Islington 3. Bexley 19. Kensington and Chelsea 4. Brent 20. Kingston upon Thames 5. Bromley 21. Lambeth 6. Camden 22. Lewisham 7. Croyd on 23. Merton 8. Ealing 24. Newham 9. Enfield 25. Redbridge 10. Greenwich 26. Richmond upon Thames 11. Hackney 27. Southwark 12. Hammersmith and Fulham 28. Sutton 13. Haringey 29. Tower Hamlets 14.