Print This Article [ PDF ]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerald Cycling Trails

CYCLING GUIDE Austria Italia Slovenia W M W O W .C . A BI RI Emerald KE-ALPEAD Cycling Trails GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE CYCLING GUIDE 3 Content Emerald Cycling Trails Circular cycling route Only few cycling destinations provide I. 1 Tolmin–Nova Gorica 4 such a diverse landscape on such a small area. Combined with the turbulent history I. 2 Gorizia–Cividale del Friuli 6 and hospitality of the local population, I. 3 Cividale del Friuli–Tolmin 8 this destination provides ideal conditions for wonderful cycling holidays. Travelling by bicycle gives you a chance to experi- Connecting tours ence different landscapes every day since II. 1 Kolovrat 10 you may start your tour in the very heart II. 2 Dobrovo–Castelmonte 11 of the Julian Alps and end it by the Adriatic Sea. Alpine region with steep mountains, deep valleys and wonderful emerald rivers like the emerald II. 3 Around Kanin 12 beauty Soča (Isonzo), mountain ridges and western slopes which slowly II. 4 Breginjski kot 14 descend into the lowland of the Natisone (Nadiža) Valleys on one side, II. 5 Čepovan valley & Trnovo forest 15 and the numerous plateaus with splendid views or vineyards of Brda, Collio and the Colli Orientali del Friuli region on the other. Cycling tours Familiarization tours are routed across the Slovenian and Italian territory and allow cyclists to III. 1 Tribil Superiore in Natisone valleys 16 try and compare typical Slovenian and Italian dishes and wines in the same day, or to visit wonderful historical cities like Cividale del Friuli which III. 2 Bovec 17 was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list. -

From the Alps to the Adriatic

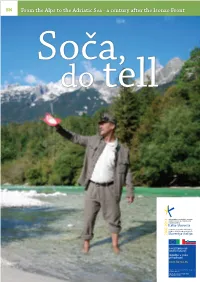

EN From the Alps to the Adriatic Sea - a century after the Isonzo Front Soča, do tell “Alone alone alone I have to be in eternity self and self in eternity discover my lumnious feathers into afar space release and peace from beyond land in self grip.” Srečko Kosovel Dear travellers Have you ever embraced the Alps and the Adriatic with by the Walk of Peace from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea that a single view? Have you ever strolled along the emerald runs across green and diverse landscape – past picturesque Soča River from its lively source in Triglav National Park towns, out-of-the-way villages and open fireplaces where to its indolent mouth in the nature reserve in the Bay of good stories abound. Trieste? Experience the bonds that link Italy and Slove- nia on the Walk of Peace. Spend a weekend with a knowledgeable guide, by yourself or in a group and see the sites by car, on foot or by bicycle. This is where the Great War cut fiercely into serenity a century Tourism experience providers have come together in the T- ago. Upon the centenary of the Isonzo Front, we remember lab cross-border network and together created new ideas for the hundreds of thousands of men and boys in the trenches your short break, all of which can be found in the brochure and on ramparts that they built with their own hands. Did entitled Soča, Do Tell. you know that their courageous wives who worked in the rear sometimes packed clothing in the large grenades instead of Welcome to the Walk of Peace! Feel the boundless experi- explosives as a way of resistance? ences and freedom, spread your wings among the vistas of the mountains and the sea, let yourself be pampered by the Today, the historic heritage of European importance is linked hospitality of the locals. -

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10

United Nations ECE/MP.WAT/2015/10 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 13 November 2015 English only Economic Commission for Europe Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes Seventh session Budapest, 17–19 November 2015 Item 4(i) of the provisional agenda Draft assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin Assessment of the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus in the Isonzo/Soča River Basin* Prepared by the secretariat with the Royal Institute of Technology Summary At its sixth session (Rome, 28–30 November 2012), the Meeting of the Parties to the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes requested the Task Force on the Water-Food-Energy-Ecosystems Nexus, in cooperation with the Working Group on Integrated Water Resources Management, to prepare a thematic assessment focusing on the water-food-energy-ecosystems nexus for the seventh session of the Meeting of the Parties (see ECE/MP.WAT/37, para. 38 (i)). The present document contains the scoping-level nexus assessment of the Isonzo/Soča River Basin with a focus on the downstream part of the basin. The document is the result of an assessment process carried out according to the methodology described in publication ECE/MP.WAT/46, developed on the basis of a desk study of relevant documentation, an assessment workshop (Gorizia, Italy; 26-27 May 2015), as well as inputs from local experts and officials of Italy. Updates in the process were reported at the meetings of the Task Force. -

Thomas RAINER, Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER, Gerd RANTITSCH, Uroš HERLEC & Marko VRABEC

Austrian Journal of Earth Sciences Volume 102/2 Vienna 2009 Organic maturity trends across the Variscan discordance in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone (Slovenia, Austria, Italy): Variscan versus Alpidic thermal overprint_________ Thomas RAINER1)3)*), Reinhard F. SACHSENHOFER1), Gerd RANTITSCH1), Uroš HERLEC2) & Marko VRABEC2) 1) KEYWORDS Mining University Leoben, Department for Applied Geosciences and Geophysics, 8700 Leoben, Austria; 2) University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, Department of Geology, Vitrinite reflectance Variscan Discordance 2) Aškerčeva 12, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia; Northern Dinarides 3) Present Address: OMV Exploration & Production GmbH, Trabrennstrasse 6-8, 1020 Wien, Austria; Southern Alps Carboniferous *) Corresponding author, [email protected] Eastern Alps Abstract In the Southern Alps and the northern Dinarides the main Variscan deformation event occurred during Late Carboniferous (Bashki- rian to Moscovian) time. It is represented locally by an angular unconformitiy, the “Variscan discordance”, separating the pre-Variscan basement from the post-Variscan (Moscovian to Cenozoic) sedimentary cover. The main aim of the present contribution is to inves- tigate whether a Variscan thermal overprint can be detected and distinguished from an Alpine thermal overprint due to Permo-Meso- zoic basin subsidence in the Alpine-Dinaric Transition Zone in Slovenia. Vitrinite reflectance (VR) is used as a temperature sensitive parameter to determine the thermal overprint of pre- and post-Variscan sedimentary successions in the eastern part of the Southern Alps (Carnic Alps, South Karawanken Range, Paški Kozjak, Konjiška Gora) and in the northern Dinarides (Sava Folds, Trnovo Nappe). Neither in the eastern part of the Southern Alps, nor in the northern Dinarides a break in coalification can be recognized across the “Variscan discordance”. -

HIKING in SLOVENIA Green

HIKING IN SLOVENIA Green. Active. Healthy. www.slovenia.info #ifeelsLOVEnia www.hiking-biking-slovenia.com |1 THE LOVE OF WALKING AT YOUR FINGERTIPS The green heart of Europe is home to active peop- le. Slovenia is a story of love, a love of being active in nature, which is almost second nature to Slovenians. In every large town or village, you can enjoy a view of green hills or Alpine peaks, and almost every Slove- nian loves to put on their hiking boots and yell out a hurrah in the embrace of the mountains. Thenew guidebook will show you the most beauti- ful hiking trails around Slovenia and tips on how to prepare for hiking, what to experience and taste, where to spend the night, and how to treat yourself after a long day of hiking. Save the dates of the biggest hiking celebrations in Slovenia – the Slovenia Hiking Festivals. Indeed, Slovenians walk always and everywhere. We are proud to celebrate 120 years of the Alpine Associati- on of Slovenia, the biggest volunteer organisation in Slovenia, responsible for maintaining mountain trails. Themountaineering culture and excitement about the beauty of Slovenia’s nature connects all generations, all Slovenian tourist farms and wine cellars. Experience this joy and connection between people in motion. This is the beginning of themighty Alpine mountain chain, where the mysterious Dinaric Alps reach their heights, and where karst caves dominate the subterranean world. There arerolling, wine-pro- ducing hills wherever you look, the Pannonian Plain spreads out like a carpet, and one can always sense the aroma of the salty Adriatic Sea. -

HISTORY of the 87Th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY

HISTORY of the 87th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY George F. Earle Captain, 87th Mountain Infantry 1945 HISTORY of the 87th MOUNTAIN INFANTRY in ITALY 3 JANUARY 1945 — 14 AUGUST 1945 Digitized and edited by Barbara Imbrie, 2004 CONTENTS PREFACE: THE 87TH REGIMENT FROM DECEMBER 1941 TO JANUARY 1945....................i - iii INTRODUCTION TO ITALY .....................................................................................................................1 (4 Jan — 16 Feb) BELVEDERE OFFENSIVE.........................................................................................................................10 (16 Feb — 28 Feb) MARCH OFFENSIVE AND CONSOLIDATION ..................................................................................24 (3 Mar — 31 Mar) SPRING OFFENSIVE TO PO VALLEY...................................................................................................43 (1 Apr — 20 Apr) Preparation: 1 Apr—13 Apr 43 First day: 14 April 48 Second day: 15 April 61 Third day: 16 April 75 Fourth day: 17 April 86 Fifth day: 18 April 96 Sixth day: 19 April 99 Seventh day: 20 April 113 PO VALLEY TO LAKE GARDA ............................................................................................................120 (21 Apr — 2 May) Eighth day: 21 April 120 Ninth day: 22 April 130 Tenth day: 23 April 132 Eleventh and Twelfth days: 24-25 April 149 Thirteenth day: 26 April 150 Fourteenth day: 27 April 152 Fifteenth day: 28 April 155 Sixteenth day: 29 April 157 End of the Campaign: 30 April-2 May 161 OCCUPATION DUTY AND -

Nuovo Regolamento Di Polizia Urbana

UNION TERITORIÂL INTERCOMUNÂL DAL NADISON - NEDIŠKA MEDOBČINSKA TERITORIALNA UNIJA REGOLAMENTO DI POLIZIA URBANA NORME PER LA CIVILE CONVIVENZA BUTTRIO CIVIDALE DRENCHIA GRIMACCO MANZANO DEL FRIULI MOIMACCO PREMARIACCO PREPOTTO PULFERO REMANZACCO SAN GIOVANNI SAN LEONARDO SAN PIETRO SAVOGNA STREGNA AL NATISONE AL NATISONE 1 UNION TERITORIÂL INTERCOMUNÂL DAL NADISON - NEDIŠKA MEDOBČINSKA TERITORIALNA UNIJA INDICE TITOLO I DISPOSIZIONI GENERALI Art. 1 Finalità, oggetto e ambito di applicazione p. 5 Art. 2 Procedure per l'accertamento delle violazioni e per l'applicazione p. 6 delle Sanzioni amministrative Art. 3 Sospensione delle autorizzazioni, dei nulla osta e delle p. 6 autorizzazioni in deroga previste dalle norme del Regolamento per lo svolgimento di determinate attività Art. 4 Accertamento delle violazioni p. 7 TITOLO II NORME DI COMPORTAMENTO CAPO I SICUREZZA URBANA, PUBBLICA INCOLUMITÀ E FRUIZIONE DEGLI SPAZI PUBBLICI – ORDINE DI ALLONTANAMENTO Art. 5 Incolumità pubblica e Sicurezza Urbana - Definizioni p. 7 Art. 6 Zone urbane di particolare rilevanza dove operano l’ordine di p. 8 allontanamento e la limitazione degli orari di somministrazione e vendita degli alcolici Art. 7 Fruibilità di spazi ed aree pubbliche – divieto di occupazione del p. 8 suolo aperto all’uso pubblico Art. 8 Divieto di stazionamento lesivo del diritto di circolazione p. 9 Art. 9 Limitazione degli orari per la vendita e per la somministrazione di p. 9 alcolici Art. 10 Procedure per l’adozione dell’ordine di allontanamento p. 10 Art. 11 Norme comportamentali per la partecipazione a manifestazioni p. 11 dinamiche Art. 12 Provvedimenti a tutela della vivibilità urbana e di contrasto al p. 11 degrado e all’abuso di sostanze alcoliche CAPO II DECORO E ATTI VIETATI SULLE AREE PUBBLICHE Art. -

Crayfish of the Upper Soca and Upper Sava Rivers, Slovenia

Bull. Fr. Pêche Piscic. (1997)347:721-729 — 721 — CRAYFISH OF THE UPPER SOCA AND UPPER SAVA RIVERS, SLOVENIA. Y. MACHINO 13 rue Montorge, 38000 Grenoble, France. Reçu le 04 juillet 1997 Received 04 July, 1997 Accepté le 29 août 1997 Accepted 29 August, 1997 ABSTRACT Crayfish biogeography of northwestern Slovenia was studied in the Upper Soca River (Mediterranean drainage) and the Sava Dolinka River (Danubian drainage). The Mediterranean drainage has white-clawed crayfish (Austropotamobius pallipes) and the Danubian drainage has stone crayfish (A. torrentium). Morphological data of these A. pallipes suggest that the Slovenian white-clawed crayfish belong to the Austropotamobius pallipes italicus complex. The biogeographic and morphological data support the present general knowledge that in Slovenia the white-clawed crayfish belongs to a Po-Adriatic fauna and the stone crayfish to a Danubian fauna. A third species, the noble crayfish (Astacus astacus), was found in Danubian waters, but its biogeographic meaning may not be significant because the species is present in, and has been introduced into, waters of both the Mediterranean and Danubian drainages. The noble crayfish from a Slovenian lake, Blejsko jezero, has certain morphological characteristics that require additional investigations before its taxonomic position can be clarified. The stone crayfish of the Sava Dolinka now survives in only a few sites, relics of a former wider distribution destroyed by human activities. On the other hand, the white-clawed crayfish of the Soca is still distributed widely. But it is timely to consider their protection because the Soca region is now under major tourist development pressure. Key-words : Austropotamobius pallipes, Austropotamobius torrentium, Astacus astacus, biogeography, taxonomy, protection, Slovenia. -

Javni Prevozi V Biosfernem Območju

TRIGLAV NATIONAL PARK 1 TRIGLAVSKI NARODNI PARK TRIGLAV NATIONAL PARK 1.7.—31.8. JAVNI PREVOZ V BIOSFERNEM OBMOCJU JULIJSKE ALPE · POLETJE | PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN BIOSPHERE RESERVE JULIAN ALPS SUMMER letnik 11, št. 12 Year 11, № 12 · 2021 TRIGLAVSKI NARODNI PARK PRAZNUJE • ZA OBISKOVALCE TRIGLAV NATIONAL PARK IS CELEBRATING • FOR NATIONAL PARK NARODNEGA PARKA • NAJ VAS NARAVA ZAPELJE - BOHINJ • VISITORS • MOVED BY NATURE - BOHINJ • THE SOCA VALLEY - WE DOLINA SOCE - PUSTIM SE ZAPELJATI • ZEMLJEVID • AVTOBUSNI TAKE YOU THERE • MAP • BUS TRIPS IN THE SURROUNDINGS OF BLED IZLETI V OKOLICI BLEDA • ODKRIJMO JULIJSKE ALPE • KARTICA • DISCOVERING THE JULIAN ALPS • JULIAN ALPS CARD AND SUSTAINABLE JULIJSKE ALPE IN TRAJNOSTNA MOBILNOST MOBILITY United Nations Man and Educational, Scientific and the Biosphere Cultural Organization Programme ODGOVORNI TURIZEM JE ZDAJ PRILOŽNOST NAŠIH RESPONSIBLE TOURISM IS NOW THE OPPORTUNITY OF OUR GENERACIJ. GENERATION. Postanite del vizije pri ustvarjanju zelene prihodnosti ter uporabite brezplačne in ugodne Become a part of the vision of creating green future and use our free transport means that are možnosti okolju prijaznih oblik prevoza. Zato vam priporočamo, da pustite svoje vozilo na enem friendly to the environment. Park your vehicle in one of the car parks in the Julian Alps Biosphere izmed parkirišč v Biosfernem območju Julijske Alpe in svoj izlet nadaljujete peš, s kolesom ali z Reserve and continue your trip on foot, by bike or with public transport. javnim prevozom. Številne označene planinske in Many designated mountaineering Poleg rednih avtobusnih linij, In addition to regular bus routes pohodniške poti vam ponujajo paths and hiking trails will provide ki Biosferno območje Julijskih connecting the Julian Alps Biosphere nepozabna doživetja, skrita tistim, ki you with a multitude of experience, Alp povezujejo z večjimi mesti Reserve with large towns and cities PEŠ BUS se vozijo po cestah. -

Jochum Et Al. 2015B Zospeum.Pdf

A peer-reviewed open-access journal Subterranean Biology 16: 123–165Taxonomic (2015) re-assessment of Zospeum isselianum 123 doi: 10.3897/subtbiol.16.5758 RESEARCH ARTICLE Subterranean Published by http://subtbiol.pensoft.net The International Society Biology for Subterranean Biology Groping through the black box of variability: An integrative taxonomic and nomenclatural re-evaluation of Zospeum isselianum Pollonera, 1887 and allied species using new imaging technology (Nano-CT, SEM), conchological, histological and molecular data (Ellobioidea, Carychiidae) Adrienne Jochum1, Rajko Slapnik2,10, Annette Klussmann-Kolb3, Barna Páll-Gergely4, Marian Kampschulte5, Gunhild Martels6, Marko Vrabec7, Claudia Nesselhauf8, Alexander M. Weigand9,10,11 1 Naturhistorisches Museum der Burgergemeinde Bern, Bernastr. 15, CH-3005 Bern, Switzerland 2 Institute of Ecology and Evolution, University of Bern, Baltzerstrasse 6, CH-3012 Bern, Switzerland. 2Drnovškova pot 2, Mekinje, 1240 Kamnik, Slovenia 3 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander König, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany 4 Department of Biology, Shinshu University, Matsumoto 390-8621, Japan 5 Uni- versitätsklinikum Giessen und Marburg GmbH-Standort Giessen, Center for Radiology, Dept. of Radiology, Klinik-Str. 33, 35385 Giessen, Germany 6 Department of Experimental Radiology, Justus-Liebig University Giessen, Biomedical Research Center Seltersberg (BFS), Schubertstrasse 81, 35392 Giessen, Germany 7 De- partment of Geology, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Engineering, Aškerčeva 12, University -

The Slovene Language in Education in Italy

The Slovene language in education in Italy European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by SLOVENE The Slovene language in education in Italy | 3rd Edition | c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province of Fryslân. © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning, 2020 ISSN: 1570 – 1239 3rd edition The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. This Regional dossier was edited by Norina Bogatec, SLORI - Slovenski raziskovalni inštitut (Slovene research institute). Maria Bidovec, Norina Bogatec, Matejka Grgič, Miran Košuta, Maja Mezgec, Tomaž Simčič and Pavel Slamič updated the previous dossier in 2004. Unless otherwise stated academic data refer to the 2017/2018 school year. Contact information of the authors of Regional dossiers can be found in the Mercator Database of Experts (www.mercator-research.eu). Anna Fardau Schukking has been responsible for the publication of this Mercator Regional dossier. Contents Contents Glossary 2 Foreword 3 Glossary -

Stories from the Land Along the Soča Guided Tours Along the Walk of Peace in the Upper Soča Region and to Slavia Veneta

Stories from the land along the Soča guided tours along the Walk of Peace in the Upper Soča Region and to Slavia Veneta Experiencing the transborder nature of the Kolovrat range panorama ¶ The Kolovrat outdoor history classroom; the story of Erwin Rommel; the story of Ernest Hemingway; the panoramic view; flora and fauna; lunch at the typical Slavia Veneta inn ....................................................... The First World War Outdoor Museum Kolovrat Within the framework of its third line of de- fence the Italian army built a whole system of defence- and gun positions and observation posts on the Kolovrat range. Part of the posi- tions on the slope of the hill Na gradu (1115 m) were restored and arranged as an outdoor museum. Opening from the ridge of the Kolovrat range is an exceptional view over the onetime battlefield of the Isonzo Front from Mt. Kanin, over the Krn range to Mt. Sveta Gora; in the opposite direction, the view reaches over the Friuli-Venezia Giulia all to the Adriatic sea. All the time a visitor has a ....................................................... feeling that he/she stands on a privileged van- The story of Ernest Hemingway tage point, at the contact of two completely The worldwide famous American author different worlds, which, however, are strong- chose the Isonzo Front for the place of events ly interdependent and bound to interact. The in his historical novel “A Farewell to Arms”. state border, which for centuries ran along The novel comprises many autobiographical these ridges and shaped the destiny of local elements. Which of them are genuine and population, did not only separate the people which are not? Did the author ever visit the from either side but also connected them due former scene of the Isonzo Front in person or to their common culture, mere survival and didn’t he? How did this literary work con- the proverbial disobedience to remote cen- tribute to better recognisability of the Soča tres of political and economic power.