Traditional Building Forms & Techniques, Ijebu-Ode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA

International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April, May, June 2011 Volume: 2 Issue: 2 Article: 4 ISSN 1309-6249 UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) POLICY IMPLEMENTATION IN FACILITIES PROVISION: Ogun State as a Case Study Prof. Dr. Kayode AJAYI Dr. Muyiwa ADEYEMI Faculty of Education Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, NIGERIA ABSTRACT The Universal Basic Education Programme (UBE) which encompasses primary and junior secondary education for all children (covering the first nine years of schooling), nomadic education and literacy and non-formal education in Nigeria have adopted the “collaborative/partnership approach”. In Ogun State, the UBE Act was passed into law in 2005 after that of the Federal government in 2004, hence, the demonstration of the intention to make the UBE free, compulsory and universal. The aspects of the policy which is capital intensive require the government to provide adequately for basic education in the area of organization, funding, staff development, facilities, among others. With the commencement of the scheme in 1999/2000 until-date, Ogun State, especially in the area of facility provision, has joined in the collaborative effort with the Federal government through counter-part funding to provide some facilities to schools in the State, especially at the Primary level. These facilities include textbooks (in core subjects’ areas- Mathematics, English, Social Studies and Primary Science), blocks of classrooms, furniture, laboratories/library, teachers, etc. This study attempts to assess the level of articulation by the Ogun State Government of its UBE policy within the general framework of the scheme in providing facilities to schools at the primary level. -

Analysis of Heavy Metals in Vegetables Sold in Ijebu-Igbo, Ijebu North Local Government, Ogun State, Nigeria

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 11, November-2015 130 ISSN 2229-5518 Analysis of Heavy Metals in Vegetables Sold in Ijebu-Igbo, Ijebu North Local Government, Ogun State, Nigeria *ABIMBOLA ‘WUNMI. A1, AKINDELE SHERIFAT. T2, JOKOTAGBA OLORUNTOBI. A2, AGBOLADE OLUFEMI .M1, AND SAM-WOBO SAMMY.O3 1Plant science and Applied Zoology Department, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State. 2Science Laboratory Technology Department, Abraham Adesanya Polytechnic, Ijebu-Igbo, Ogun State. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria Abstract - A preliminary market study was conducted to assess the level of certain heavy metal in selected vegetable sold in Obada market and Atikori market, harvested from three farm-lands located in Ayesan, Dagbolu and Osunbodepo in Ijebu North Local Area Government. The vegetables were bitter-leaf (Vernonia amygdalina), fluted pumpkin (Talfaria occidentalis), water-leaf (Talinum triangulare), and jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius). The samples were analysed for heavy metals (Cr, Mn, Ni, Co, Cu, Cd, Zn, Pb, and Fe) using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS, Perkin Elmer model 2130), in accordance with AOAC. The result obtained showed, Jute Mallow had highest value of Zinc with 111.23 and lowest value of Co with 3.50; fluted Pumpkin had highest value of Mn with 45.50 and lowest value in CO with 1.75; Water Leaf had Zn with highest value 186.75 and Cd has the lowest; Bitter Leaf had Zn with 90.50 and Cd with 1.50. Keywords - Farm, Heavy Metals, Site, spectrophotometer, Vegetables —————————— —————————— INTRODUCTION vegetables contamination with heavy metals Heavy metal contamination of vegetables cannot derives from factors such as the application of be under-estimated as these foodstuffs are fertilizers, sewage sludge or irrigation with important componentsIJSER of human diet. -

Ijebu-Ode Ile-Ife Truck Road South- West Nigeria

Ijebu-Ode Ile-Ife Truck Road South- West Nigeria. Client: Federal Ministry of Works Lagos- Nigeria. Location: Osun- Ogun State - Nigeria. Date: 1977 The Nigerian Federal Ministry of Works commissioned Allott (Nigeria) Limited to undertake the location, survey and detailed design of a new trunk road to link the towns of Ijebu Ode Ile-Ife and Sekona which lie to the north of Lagos and south east of Ibadan. The route over which this road was to pass was through thick tropical rain forest and sparsely populated. Access was difficult and the existing dirt roads were impassable in the rainy season. A suitable was located from a study of aerial photography and a ground reconnaissance which was followed by a traverse survey. The detailed design of the road’s alignment was carried out using the latest computer-aided techniques, further to the results of the topographical survey. Other field work Included a hydrological survey and a borehole survey. On completion of the design, the centre line of the new road was staked out by the field team. The proposed road had a two lane carriageway with bituminous surfacing, a crushed stone base and a laterite sub- base. The total length was 140km and there were a total of 13 bridges. The two major structures were the 150m long 6-span bridge over the River Oshun and the 75m long 3-span bridge over the River Shasha. These have in-situ reinforced concrete voided decks supported on reinforced concrete piers. The location of sources of suitable road Construction materials was an important part of the design. -

Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard

The case of Ibadan, Nigeria by Laurent Fourchard Contact: Source: CIA factbook Laurent Fourchard Institut Francais de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA), University of Ibadan Po Box 21540, Oyo State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION: THE CITY A. URBAN CONTEXT 1. Overview of Nigeria: Economic and Social Trends in the 20th Century During the colonial period (end of the 19th century – agricultural sectors. The contribution of agriculture to 1960), the Nigerian economy depended mainly on agri- the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from 60 percent cultural exports and on proceeds from the mining indus- in the 1960s to 31 percent by the early 1980s. try. Small-holder peasant farmers were responsible for Agricultural production declined because of inexpen- the production of cocoa, coffee, rubber and timber in the sive imports and heavy demand for construction labour Western Region, palm produce in the Eastern Region encouraged the migration of farm workers to towns and and cotton, groundnut, hides and skins in the Northern cities. Region. The major minerals were tin and columbite from From being a major agricultural net exporter in the the central plateau and from the Eastern Highlands. In 1960s and largely self-sufficient in food, Nigeria the decade after independence, Nigeria pursued a became a net importer of agricultural commodities. deliberate policy of import-substitution industrialisation, When oil revenues fell in 1982, the economy was left which led to the establishment of many light industries, with an unsustainable import and capital-intensive such as food processing, textiles and fabrication of production structure; and the national budget was dras- metal and plastic wares. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu -

Nigeria: Badoo Cult, Including Areas of Operation and Activities; State Response to the Group; Treatment of Badoo Members Or Alleged Members (2016-December 2019)

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of... https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?... Nigeria: Badoo cult, including areas of operation and activities; state response to the group; treatment of Badoo members or alleged members (2016-December 2019) 1. Overview Nigerian media sources have reported on the following: "'Badoo Boys'" (The Sun 27 Aug. 2019); "Badoo cult" (Vanguard with NAN 2 Jan. 2018; This Day 22 Jan. 2019); "Badoo gang" (Business Day 9 July 2017); "Badoo" (Vanguard with NAN 2 Jan. 2018). A July 2017 article in the Nigerian newspaper Business Day describes Badoo as "[a] band of rapists and ritual murderers that has been wreaking havoc on residents of Ikorodu area" of Lagos state (Business Day 9 July 2017). The article adds that [t]he Badoo gang’s reign of terror has reportedly spread throughout Lasunwon, Odogunyan, Ogijo, Ibeshe Tutun, Eruwen, Olopomeji and other communities in Ikorodu. Their underlying motivation seems to be ritualistic in nature. The gang members are reported to wipe their victims’ private part[s] with a white handkerchief after each rape for onward delivery to their alleged sponsors; slain victims have also been said to have had their heads smashed with a grinding stone and their blood and brain soaked with white handkerchiefs for ritual purposes. Latest reports quoted an arrested member of the gang to have told the police that each blood-soaked handkerchief is sold for N500,000 [Nigerian Naira, NGN] [approximately C$2,000]. (Business Day 9 July 2017) A 2 January 2018 report in the Nigerian newspaper Vanguard provided the following context: It all started after a suspect, described by some residents of Ikorodu area as a "serial rapist and ritual killer," was arrested at Ibeshe. -

Wellington Park Historic Tracks and Huts Network Comparative Analysis

THE HISTORIC TRACK & HUT NETWORK OF THE HOBART FACE OF MOUNT WELLINGTON Interim Report Comparative Analysis & Significance Assessment Anne McConnell MAY 2012 For the Wellington Park Management Trust, Hobart. Anne D. McConnell Consultant - Cultural Heritage Management, Archaeology & Quaternary Geoscience; GPO Box 234, Hobart, Tasmania, 7001. Background to Report This report presents the comparative analysis and significance assessment findings for the historic track and hut network on the Hobart-face of Mount Wellington as part of the Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project. This report is provided as the deliverable for the second milestone for the project. The Wellington Park Historic Track & Hut Network Assessment Project is a project of the Wellington Park Management Trust. The project is funded by a grant from the Tasmanian government Urban Renewal and Heritage Fund (URHF). The project is being undertaken on a consultancy basis by the author, Anne McConnell. The data contained in this assessment will be integrated into the final project report in approximately the same format as presented here. Image above: Holiday Rambles in Tasmania – Ascending Mt Wellington, 1885. [Source – State Library of Victoria] Cover Image: Mount Wellington Map, 1937, VW Hodgman [Source – State Library of Tasmania] i CONTENTS page no 1 BACKGROUND - THE EVOLUTION OF 1 THE TRACK & HUT NETWORK 1.1 The Evolution of the Track Network 1 2.2 The Evolution of the Huts 18 2 A CONTEXT FOR THE TRACK & HUT 29 NETWORK – A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS 2.1 -

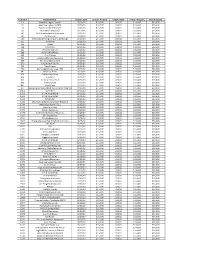

2021-02-09 Final Disbursement Spreadsheet

License # Establishment Check 1 Date Check 1 Amount Check 2 Date Check 2 Amount Total Awarded 51 American Legion Post #1 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 59 American Legion Post #28 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 74 Pancho's Villa Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 83 Asia GarDens/BranDy's 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 107 Bella Vista Pizzaria & Restaurant 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 140 The Blue Fox 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 200 Matanuska Brewing ComPany, Anchorage 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 217 Williwaw 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 225 Koots 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 258 Club Paris 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 321 Chili's Bar anD Grill 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 398 Buffalo WilD Wings 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 434 Fiori D'Italia 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 629 La Cabana Mexican Restaurant 11/05/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 635 Serrano's Mexican Grill 11/12/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 670 Long Branch Saloon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 733 Twin Dragon 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 750 Anchorage Moose LoDge 1534 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 761 MulDoon Pizza 11/19/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 814 The BraDley House 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 826 Tequila 61 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 842 The New Peanut Farm 10/29/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 888 Pizza OlymPia 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 891 Pizza Plaza 12/11/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 Anchorage977 Brewing ComPany (NeeD sPecial email if aPPlieD for Tier11/05/20 A) $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1064 Sorrento's 10/23/20 $15,000 1/20/21 $15,000 $30,000 1203 V.F.W. -

Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture

Anno 1778 m # # PHILLIPS ACADEMY # # # OLIVER-WENDELL- HOLMES # # # LIBRARY # # # # Lulie Anderson Fuess Fund The discovery and recording of the “vernacular” architec¬ ture of the Americas was a unique adventure. There were no guide books. Sibyl Moholy-Nagy’s search involved some 15,000 miles of travel between the St. Lawrence River and the Antilles by every conceivable means of transportation. Here in this handsome volume, illustrated with 105 photo¬ graphs and 21 drawings, are some of the amazing examples of architecture—from 1600 on—to be found in the Americas. Everybody concerned with today’s problems of shelter will be fascinated by the masterly solutions of these natural archi¬ tects who settled away from the big cities in search of a us architecture is a fascinating happier, freer, more humane existence. various appeal: Pictorially excit- ly brings native architecture alive is many provocative insights into mericas, their culture, the living and tradition. It explores, for the )f unknown builders in North and litectural heritage. Never before the beautiful buildings—homes, nills and other structures—erected architects by their need for shelter 3 settlers brought a knowledge of irt of their former cultures and their new surroundings that they ures both serviceable and highly art. The genius revealed in the ptation of Old World solutions to sibyl moholy-nagy was born and educated in Dresden, Ger¬ choice of local materials; in com- many. In 1931 she married the noted painter, photographer ationships might well be the envy and stage designer Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. After living in Hol¬ land and England, they settled in Chicago where Moholy- Nagy founded the Institute of Design for which Mrs. -

2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 4(8), 2197-2204

ISSN: 2320-5407 Int. J. Adv. Res. 4(8), 2197-2204 Journal Homepage: - www.journalijar.com Article DOI: Article DOI: 10.21474/IJAR01/1707 DOI URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/1707 RESEARCH ARTICLE IMPACT OF TEXTILE FRILLS ON THE EQUESTRIAN THRILLS AT OJUDE OBA FESTIVAL. Margaret Olugbemisola Areo (Ph.D). Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P.M.B 4000, Ogbomoso, Oyo State. Nigeria. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Manuscript Info Abstract ……………………. ……………………………………………………………… Manuscript History Equestrian figures are an integral part of Ojude – Oba festival which is celebrated annually in Ijebu – Ode, Southwestern Nigeria, in Received: 12 July 2016 commemoration of the introduction of Islam into the town. The horses Final Accepted: 19 August 2016 which are colourfully decorated with textile materials to the level of Published: September 2016 art lend excitement to the festival, as the riders display their Key words:- equestrian prowess in a parade to the delight of onlookers at the Textiles, Equestrian display, Ojude – festival. While many are enthralled by the kaleidoscope of colours and Oba. the entertaining display, the impact of textiles in bringing this to the fore is downplayed, and lost to the onlookers and as a result has up to now not been given a scholastic study. This study, a descriptive appraisal of Ojude - Oba festival, through personal participatory observation, consultation of few available literature materials, oral interviews and pictorial imagery, brings to the fore the role of textiles in the colourful display of equestrian figures at Ojude – Oba. Copy Right, IJAR, 2016,. All rights reserved. …………………………………………………………………………………………………….... Introduction:- Ojude – Oba festival is celebrated annually in Ijebu – Ode in Southwestern Nigeria two days after the muslim Eid el - Kabir. -

COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd

2558 Schillinger Rd. • 219-7761 COFFEE, SMOOTHIES, LUNCH & BEERS. CHUCK’S FISH ($$) 966 Government St.• 408-9001 LAID-BACK EATERY & FISH MARKET 3249 Dauphin St. • 479-2000 5460 Old Shell Rd. • 344-4575 SEAFOOD AND SUSHI BAMBOO 1477 Battleship Pkwy. • 621-8366 FOY SUPERFOODS ($) 551 Dauphin St.• 219-7051 STEAKHOUSE & SUSHI BAR ($$) RIVER SHACK ($-$$) 119 Dauphin St.• 307-8997 SERDA’S COFFEEHOUSE ($) TRADITIONAL JAPANESE WITH HIBACHI GRILLS SEAFOOD, BURGERS & STEAKS COFFEE, LUNCHES, LIVE MUSIC & GELATO CORNER 251 ($-$$) 650 Cody Rd. S • 300-8383 6120 Marina Dr. • Dog River • 443-7318 GULF COAST EXPLOREUM CAFE ($) 3 Royal St. S. • 415-3000 HIGH QUALITY FOOD & DRINKS BANGKOK THAI ($-$$) THE GRAND MARINER ($-$$) HOMEMADE SOUPS & SANDWICHES 1539 US-98 • Daphne • 517-3963 251 Government St • 432-8000 DELICIOUS, TRADITIONAL THAI CUISINE 65 Government St. • 208-6815 28600 US 98 • Daphne • 626-5286 LOCAL SEAFOOD & PRODUCE DAUPHIN’S ($$-$$$) 6036 Rock Point Rd. • 443-7540 $10/PERSON • $$ 10-25/PERSON • $$$ OVER 25/PERSON SHELL FOOD MART ($) 3821 Airport Blvd. • 344-9995 HOOTERS ($) Co. Rd. 49 & U.S. 98• Magnolia Springs HIGH QUALITY FOOD WITH A VIEW 3869 Airport Blvd. • 345-9544 107 St. Francis St/RSA Building • 444-0200 BANZAI JAPANESE THE HARBOR ROOM ($-$$) COMPLETELY COMFORTABLE 5470 Inn Rd. • 661-9117 SIMPLY SWEET ($) RESTAURANT ($$) UNIQUE SEAFOOD 28975 US 98 • Daphne • 625-3910 CUPCAKE BOUTIQUE DUMBWAITER ($$-$$$) TRADITIONAL SUSHI & LUNCH. 64 S. Water St. • 438-4000 9 Du Rhu Dr. Suite 201 ALL SPORTS BAR & GRILL ($) 6207 Cottage Hill Rd. Suite B • 665-3003 312 Schillinger Rd./Ambassador Plaza• 633-9077 3408 Pleasant Valley Rd. • 345-9338 JAMAICAN VIBE ($) 167 Dauphin St. -

Beaches & Holiday Homes Dog-Friendly Directory

South Devon LOVES DOGS A pet-friendly holiday guide from Coast & Country Cottages Alfie Bear visits Salcombe TipsHoliday from advice local from vets, experts bloggers and The National Farmers’ Union The best forBeaches you and your & four-leggedholiday homes friend Dog-friendlyOver 100 eateries, attractionsdirectory and useful contacts SOUTH DEVON LOVES DOGS Welcome I’m Alfie, an English Springer Spaniel… Water obsessed and beach mad! I am always on the road with my human, sniffing out the very best in all things dog-friendly. Being a famous blogger allows me and my best friend Emma to travel around the country, going to prestigious events such as Crufts and staying in luxury properties like Poll Cottage in the heart of Salcombe. Together, Emma and I find our favourite dog-friendly locations, that our followers love to read about. Emma Bearman is a freelance Personally, I love Devon; it is the perfect place for a doggy photographer based in the holiday. With so many beaches to explore, I know I will Warwickshire countryside. have the best adventures. We always have to take a trip to Emma’s photographs of her beloved canine pal ‘Alfie Bear’, East Portlemouth, with miles of sandy beach and endless quickly turned into a full-time swimming. I love stopping at our favourite pub, The Victoria job and fully functioning online Inn, for a bite to eat on the way home. blog with thousands of fans visiting www.alfiebear.com. Alfie Bear Star of dog blog alfiebear.com We know how lucky we are to live and work in this Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty