Isjs - Transactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON the CHRONOLOGY of the TATTVÓRTHA SÚTRA and SOME EARLY COMMENTARIES* (Published In: Wiener Zeitschrift Für Die Kunde Südasiens 29 (1985), Pp

THE CHRONOLOGY OF THE TATTVÓRTHA SÚTRA 1 JOHANNES BRONKHORST ON THE CHRONOLOGY OF THE TATTVÓRTHA SÚTRA AND SOME EARLY COMMENTARIES* (published in: Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens 29 (1985), pp. 155-184) I. Siddhasena Gaˆi’s È¥kå 1. Of the commentaries to be studied this is by far the most recent one. It comments on the Tattvårtha SËtra and the Tattvårthådhigama Bhå∑ya, and therefore postdates both. More helpful information for determining its date consists in the mention of Dharmak¥rti and his Pramåˆavinißcaya in the commentary on TS 5.31 (I, p. 397). Dharmak¥rti lived in the seventh century at the latest (about 600-660 A.D. according to Frauwallner 1961: 137f.; Lindtner 1980 argues for ca. 530-600). Siddhasena Gaˆi lived after this. He appears to be referred to under the name ‘Gandhahastin’ in Í¥lå∫ka’s commentary on the Ócårå∫ga SËtra (p. 1 and 55 [82]), because ‘Gandhahastin’ is used as a name of Siddhasena Gaˆi in several works (Sukhlal 1974: Intr. p. 55 f.). Í¥lå∫ka wrote in the middle of the 9th century or soon after that (Kapadia 1941: 197). Siddhasena Gaˆi wrote before this. A further specification of Siddhasena Gaˆi’s date is possible, as follows. The Tattvårthådhigama Bhå∑ya on sËtra 9.22 explains the word pråyaßcitta ‘atonement’ and makes in that connection the following observation (II, p. 254): cit¥ sañjñånavißuddhyo˙ dhåtu˙ | tasya cittam iti bhavati ni∑†håntam auˆådikaµ ca | “The root is ‘citÁ in [the senses] “ideation” and “purification”’. Citta is its [derivative], ending in the suffix of the past participle (viz., -ta) and belonging to the words derived with an Uˆådi suffix”. -

Distinguishing the Two Siddhasenas

Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, Vol. 48, No. 1, December 1999 Distinguishing the Two Siddhasenas FUJINAGA Sin Sometimes different philosophers in the same traditiion share the same name. For example, Dr. E. Frauwallner points out that there are two Buddhist philosophers who bear the name Vasubandu." Both of these philosophers are believed to have written important works that are attributed to that name. A similar situation can sometimes be found in the Jaina tradition, and sometimes the situation arises even when the philosophers are in different traditions. For exam- ple, there are two Indian philosophers who are called Haribhadra, one in the Jain tradition, and one in the Buddhist tradition. This paper will argue that one philosopher named Siddhasena, the author of the famous Jaina work, the Sammatitarka, should be distinguished from another philosopher with the same name, the author of the Nvavavatara, a work which occupies an equally important position in Jaina philosophy- 2) One reason to argue that the authors of these works are two different persons is that the works are written in two different languages : the Sammatitarka in Prakrit ; the Nvavavatara in Sanskrit. In the Jaina tradition, it is extremely unusual for the same author to write philosophical works in different languages, the usual languages being either Prakrit or Sanskrit, but not both. Of course, the possibility of one author using two languages cannot be completely eliminated. For example, the Jaina philosopher Haribhadra uses both Prakrit and Sanskrit. But even Haribhadra limits himself to one language when writing a philosophical .work : his philosophical works are all written in Sanskrit, and he uses Prakrit for all of his non-philosophical works. -

Bhakti Movement

TELLINGS AND TEXTS Tellings and Texts Music, Literature and Performance in North India Edited by Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Orsini, Francesca and Butler Schofield, Katherine (eds.), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#copyright All external links were active on 22/09/2015 and archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: https://archive.org/web/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http:// www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-102-1 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-103-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-104-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-105-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9978-1-78374-106-9 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0062 King’s College London has generously contributed to the publication of this volume. -

Guidences of Jainism the Navakar Mantra

GUIDENCES OF JAINISM By Bhadrabahu Vijay Translated by: Shri K. Ramappa, M.A., B.Ed. First Edition Published by: Shri Vishwa Kalyan Prakashan Trust Near Kamboi Nagar Mrhsana 384002 Gujarat THE NAVAKAR MANTRA The hymn of invocation Namo Arihantanam I bow in veneration to Arihantas (the destroyers of our inner enemies viz., Karmas). Namo Siddhanam I bow in veneration to Siddhas. (The souls that are perfect through the destruction of the Karmas.) Namo Ayariyanam I bow in veneration to Acharyas (The Head Sadhus of the four- fold Jain Sangh). Namo Uvajjhayanam I bow in veneration to Upadhyayas (The learned Sadhus who illustrate the Scriptures). Namo loye savva sahunam I bow in veneration to all Sadhus in the world. (Those who are pursuing the path of Moksha or salvation.) Eso pancha namukkaro Savva pävappanäsano Mangalänam cha savvesim Padhamam havai mangalam This five-fold salutation destroys all sins and is the most auspicious one amongst all auspicious things. This is the greatest hymn of invocation in Jainism. Every follower of Jainism repeats this hymn with devotion. This is the most efficacious hymn. Create PDF with PDF4U. If you wish to remove this line, please click here to purchase the full version WHAT IS THE JAIN DHARMA OR JAINISM? Before we understand the meaning of the Jain dharma, it is absolutely necessary that we should have a thorough knowledge of the word, dharma or religion because for thousands of years, innumerable wrong notions about dharma hace been nourished and held by people. Dharma or religion is neither a cult nor a creed; nor it is a reserved ystem of any community. -

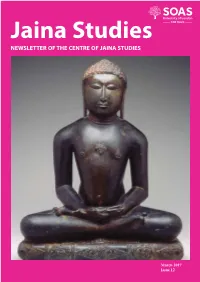

Newsletter of the Centre of Jaina Studies

Jaina Studies NEWSLETTER OF THE CENTRE OF JAINA STUDIES March 2017 Issue 12 CoJS Newsletter • March 2017 • Issue 12 Centre of Jaina Studies Members SOAS MEMBERS Honorary President Professor Christine Chojnacki Muni Mahendra Kumar Ratnakumar Shah Professor J. Clifford Wright (University of Lyon) (Jain Vishva Bharati Institute, India) (Pune) Chair/Director of the Centre Dr Anne Clavel Dr James Laidlaw Dr Kanubhai Sheth Dr Peter Flügel (Aix en Province) (University of Cambridge) (LD Institute, Ahmedabad) Dr Crispin Branfoot Professor John E. Cort Dr Basile Leclère Dr Kalpana Sheth Department of the History of Art (Denison University) (University of Lyon) (Ahmedabad) and Archaeology Dr Eva De Clercq Dr Jeffery Long Dr Kamala Canda Sogani Professor Rachel Dwyer (University of Ghent) (Elizabethtown College) (Apapramśa Sāhitya Academy, Jaipur) South Asia Department Dr Robert J. Del Bontà Dr Andrea Luithle-Hardenberg Dr Jayandra Soni Dr Sean Gaffney (Independent Scholar) (University of Tübingen) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Saryu V. Doshi Professor Adelheid Mette Dr Luitgard Soni Dr Erica Hunter (Mumbai) (University of Munich) (University of Marburg) Department of the Study of Religions Professor Christoph Emmrich Gerd Mevissen Dr Herman Tieken Dr James Mallinson (University of Toronto) (Berliner Indologische Studien) (Institut Kern, Universiteit Leiden) South Asia Department Dr Anna Aurelia Esposito Professor Anne E. Monius Professor Maruti Nandan P. Tiwari Professor Werner Menski (University of Würzburg) (Harvard Divinity School) (Banaras Hindu University) School of Law Dr Sherry Fohr Dr Andrew More Dr Himal Trikha Professor Francesca Orsini (Converse College) (University of Toronto) (Austrian Academy of Sciences) South Asia Department Janet Leigh Foster Catherine Morice-Singh Dr Tomoyuki Uno Dr Ulrich Pagel (SOAS Alumna) (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, Paris) (Chikushi Jogakuen University) Department of the Study of Religions Dr Lynn Foulston Professor Hampa P. -

The Sixteen Bhavanas in Jainism the Picture Shows King Shrenik And

JAINA’s Quaterly Publication The Sixteen Bhavanas in Jainism The Picture shows King Shrenik and Anathi Muni depicting Asharan Bhavana JAIN DIGEST 2 A Publication of the Federation of Jain Associations in North America (JAINA) email: [email protected] JAINA is an umbrella organization of local Jain Associations in U.S.A. and Canada. The purpose of the organization is to preserve, practice, and promote Jain Dharma and Jain Way of life. JAINA Headquarters email: [email protected], Website: www.jaina.org JAINA Executive Committee JAIN DIGEST Editorial Team 310-721-5947 President Gunvant Shah email: [email protected] [email protected] Jain Digest Committee Chairman First VP: Mahesh Wadher Mahesh Wadher [email protected] Editors Secretary: Haresh Shah Dilip Parekh [email protected] Sanjay Bhandari Reena Shah Treasurer: Atul Shah Giriraj Jain [email protected] Art and Design VP Northeast: Jayshree Shah Jayana Shah [email protected] Rishita Dagli VP Mideast: Hita Shah [email protected] Advertisements Mahesh Wadher VP Southeast: Purvin Vakharwala [email protected] Advisors Dilip V Shah VP Midwest: Rahul Dedhia Ramesh Khandhar rahul.dedhia@gmail,com VP Southwest: Dr. Pradeep Shah [email protected] On the Cover: VP West: Koklia Doshi Bhagwan Mahavir gave us 16 Bhavanas for contemplation to [email protected] help us with our spiritual progress. The bhavanas covered in this issue are shown in orange colored circles. Bhavanas VP Canada: Kamal Jain shown in green colored circles will be covered in the next [email protected] issue. The picture shows King Shrenik and Anathi Muni depicting Asharan Bhavana. -

Prakrit, Sanskrit, and the Language Order of Premodern India

Language of the Snakes Prakrit, Sanskrit, and the Language Order of Premodern India Andrew Ollett Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 ©2015 Andrew Ollett All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Language of the Snakes Andrew Ollett Language of the Snakes is a biography of Prakrit, one of premodern India’s most important and most neglected literary languages. Prakrit was the language of a literary tradition that flourished om roughly the 1st to the 12th century . During this period, it served as a counterpart to Sanskrit, the preeminent language of literature and learning in India. Together, Sanskrit and Prakrit were the foundation for an enduring “language order” that governed the way that people thought of and used language. Language of the Snakes traces the history of this language order through the historical articulations of Prakrit, which are set out here for the first time: its invention and cultivation among the royal courts of central India around the 1st century , its representation in classical Sanskrit and Prakrit texts, the ways it is made into an object of systematic knowledge, and ultimately its displacement om the language practices of literature. Prakrit is shown to have played a critical role in the establishment of the cultural-political formation now called the “Sanskrit cosmopolis,” as shown through a genealogy of its two key practices, courtly literature (kāvya-) and royal eulogy (praśasti-). It played a similarly critical role in the emergence of vernacular textuality, as it provided a model for language practices that diverged om Sanskrit but nevertheless possessed an identity and regularity of their own. -

Siddhasena Mahâmati and Akalaóka Bhaþþa: a Revolution in Jaina Epistemology

To be published in: Companion to Classical Indian Philosophy. Edited by Matthew Kapstein, Cambridge University Press, [in press] Siddhasena Mahâmati and Akalaóka Bhaþþa: A revolution in Jaina epistemology Piotr Balcerowicz 1. Introduction Two Jaina contemporaries, a Œvetâmbara philosopher Siddhasena Mahâmati (circa 710/720– 770/780) and his younger contemporary Digambara thinker Akalaóka Bhaþþa (c. 720–780)1, are regarded by their respective sects as the fathers of Jaina logic. Even though the claims might be slightly exaggerated, both of them indeed revolutionised Jaina epistemology, by radically transforming basic epistemological concepts, which had been based on Canonical tradition. The former is credited with composing the succinct Nyâyâvatâra (Introduction to Logic; hereafter NA), and is generally confused with a pre-Diónâga thinker Siddhasena Divâkara (c. 450–500), the author of the Saômati-tarka-prakaraòa (A Treatise on Correct Reasoning).2 Despite his importance, we know basically nothing about Siddhasena Mahâmati, not even his correct full name. His seminal work belonging to the category of works in 32 verses (dvâtriôœikâ) was commented by a few authors. Siddharši-gaòin completed his commentary Nyâyâvatâra-vivåtti on 21 May 906, and Devabhadra-sûri supplied his gloss Nyâyâvatâra- þippana in the second half of the twelfth century. Œânti-sûri composed his versed commentary Nyâyâvatâra-vârttika-våtti in eleventh century. Akalaóka Bhaþþa was one of most prolific writers among the Digambaras, and his oeuvre ranges from commentaries, -

The Jain–Mimaçsa Debate on Omniscience

4 THE JAIN–MIMAM. SA DEBATE ON OMNISCIENCE Olle Qvarnström Introduction A central theme of research within the history of religious philosophy has been the debate concerning reason and revelation, which had its roots in the Greco-Roman tradition on the one side, and the Judeo-Christian tradition on the other. Initiated in the second and third century of the common era by authors such as Celsos, Porphyrius and Emperor Julian,1 it came to dominate medieval scholasticism and was brought to the fore after the Renaissance as a result of the development of natural science and biblical criticism, among other things. Today, the debate has re-emerged, and grown in momentum as well as complexity, largely due to Islamic and Christian fundamentalism.2 The result, as one might expect, has been the production of a plethora of scholarly studies that have looked at the question of reason vs. revelation from numerous angles of vision.3 To date, however, judging from the content of these studies, the scholarly community has not adequately attended the fact that, in certain respects, a similar debate took place in India. This debate originated from a religious conflict that arose between the followers of the Vedic tradition, on the one hand, and those of various non-Vedic traditions, on the other. As with the debate in the West, the Indic controversy thus had a double heritage and stemmed from an irreconcilable antagonism between those who held that man was doomed to ignorance and thus fully dependent upon revelatory scripture and those who held that man was not only predetermined for knowledge, but capable of acquiring it through his own natural faculties. -

Living Systems in Jainism: a Scientific Study

Living Systems in Jainism: A Scientific Study Narayan Lal Kachhara Kundakunda Jñānapīṭha, Indore i Living Systems in Jainism: A Scientific Study Author : Narayan Lal Kachhara, 55, Ravindra Nagar, Udaipur - 313003 [email protected] © Author ISBN: : 81-86933–62-X First Edition : 2018 Price : Rs. 350/- $ 10.00/- Publisher : Kundakunda Jñānapīṭha 584, M.G. Road, Tukoganj Indore – 452 001, India 0731 – 2545421, 2545744 [email protected] Financial support : Manohardevi Punamchand Kachhara Charitable Trust, Udaipur Printed at : Payorite Print Media Pvt. Ltd. Udaipur ii Dedicated to My son Raju Whose departure proved a turning point in my life That changed the course from Professionalism to spiritualism iii Publisher’s Note Sacred books written or compiled by Jain Acharyas are the rich source of knowledge. These texts and the commentaries written by later Acharyas are now being studied by monks and scholars in various contexts. These sources provide us guidelines and directions for meaningful living, searching the purpose of life and knowing the nature and its interactions with the living beings. The religious texts are studied from the following points of views: 1. Spiritual. The texts were primarily composed for giving the human beings the knowledge for making spiritual progress ultimately leading to the state of permanent bliss. 2. History. The texts provide historical information about the ancient period. 3. Culture and art. The texts contain information on culture and art of those times. 4. Science. The texts contain a treasure of knowledge about the realities of nature and its interaction with the life of living beings. This branch of knowledge earlier studied as philosophy is now known as science. -

Page 1 Samantabhadra, Siddhasena, and Akalanka FUJINAGA SIN

Samantabhadra, Samantabhadra, Siddhasena, and Akalarika FunNAGA SIN MIYAKONOJO NATIONAL COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY 0. 0. The two main branches of Jainism, the Di- 1. Akalanka, Digambara philosopher in the g創 nb 紅 as and Svetambaras of Jainism ,訂e gen- eighth century, has written many independent erally erally believed to have no discrepancies in the philosophical works such as Siddhiviniscaya 組 d philosophical philosophical issues. In fact, they have only N ヲ匂 avinisc αya. Among 血em, Prama!la- slightly slightly changed their doctrine in their long his- sarrzgraha with V,rtti 1 is regarded as his last and tory tory of more than 2500 ye 訂 s. Both schools, for most mature work of his career. As the title example, example, have the highly developed karma the- suggests, it is a compendium of prama!las con- ories ories which are not essentially different from taining about ninety verses in nine chapters. In each each other. Their philosophical views seem to the sixth chapter which discusses the way of have have remained monolithic through the ages. This debate (vada), Akalanka refers to three kinds of observation observation is true also when we study the Jaina hetvabhasas mentioning three Jaina philosophers ideas ideas of logic and epistemology 出 a whole. The by name. It reads: Svetambaras Svetambaras as well as the Digambaras classify 邸泊' dh α[ち ]s泊' dhas 四回ya viruddho devanandi- prama!las prama!las into two sub-divisions: praηak~a and m ちI dvedha samantabhadr 田狗践的, adir parok~a. aca 協加ianillv. 56//2 But when it comes to the details, we come across across different views between the two branches. -

Download Book

Jain Legend Jain Dharma kā Maulika Itihāsa Author Ācāryaśrī Hastī Mala Jī M.S Editors (English Version) Shugan C. Jain P. S. Surana VOLUME 2 ABRIDGED Relating to Omniscient lords and knowers of the prior canons (Part relating to Kevalīs & Pūrvadharas) 1 Editorial Jain Legend is the verbatim English translation of series of four volumes Jain Dharma kā Maulika Itihāsa (abridged) in Hindi edited by Sh. Gajsingh Rathod. The original voluminous Jain Dharma kā Maulika Itihāsa was authored by venerable Ācāryaśrī Hastīmala Jī M.S., the foremost ācārya of Sthanakavasi tradition of Jain congregation. We have been extremely careful in maintaining the content of Jain Dharma kā Maulika Itihāsa (abridged) as it is without any changes / or adding comments by us so as to retain the authentic writings of Ācāryaśrī Hastīmala Jī M.S. Thus the English translation carries his scholarship and research over an extended period of over twenty years. In this English edition, we have tried to keep some of the definitive terms of Jainism as they are and give their English equivalent (as much representative as possible) on the first occurrence and also listed at the end of this note. To appreciate their understanding and pronunciation, we have used diacritical marks for legendary names of persons / texts / places and the definitive Jain terms e.g. aṃga meaning the limb or part and commonly written as anga, etc. We express my thanks to following translators and other support staff members for their contribution to bring out Jain Legend 1. Dr.(Ms.)Uma Maheshwari Translation Volume I 2. Mrs.