Finding Little Albert: a Journey to John B. Watson's Infant Laboratory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psychological Correlates of University Students' Academic Performance: A

Psychological Bulletin © 2012 American Psychological Association 2012, Vol. 138, No. 2, 353–387 0033-2909/12/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0026838 Psychological Correlates of University Students’ Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Michelle Richardson Charles Abraham University College London University of Exeter Rod Bond University of Sussex A review of 13 years of research into antecedents of university students’ grade point average (GPA) scores generated the following: a comprehensive, conceptual map of known correlates of tertiary GPA; assessment of the magnitude of average, weighted correlations with GPA; and tests of multivariate models of GPA correlates within and across research domains. A systematic search of PsycINFO and Web of Knowledge databases between 1997 and 2010 identified 7,167 English-language articles yielding 241 data sets, which reported on 50 conceptually distinct correlates of GPA, including 3 demographic factors and 5 traditional measures of cognitive capacity or prior academic performance. In addition, 42 non-intellective constructs were identified from 5 conceptually overlapping but distinct research do- mains: (a) personality traits, (b) motivational factors, (c) self-regulatory learning strategies, (d) students’ approaches to learning, and (e) psychosocial contextual influences. We retrieved 1,105 independent correlations and analyzed data using hypothesis-driven, random-effects meta-analyses. Significant aver- age, weighted correlations were found for 41 of 50 measures. Univariate analyses revealed that demographic and psychosocial contextual factors generated, at best, small correlations with GPA. Medium-sized correlations were observed for high school GPA, SAT, ACT, and A level scores. Three non-intellective constructs also showed medium-sized correlations with GPA: academic self-efficacy, grade goal, and effort regulation. -

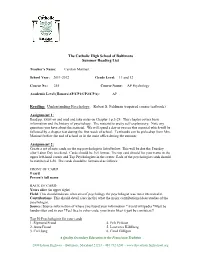

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Reading

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Teacher’s Name: Carolyn Marinari School Year: 2011-2012______________ Grade Level: 11 and 12 Course No.: 255 Course Name: AP Psychology Academic Level (Honors/AP/CP1/CP2/CPA): AP Reading: Understanding Psychology, Robert S. Feldman (required course textbook) Assignment 1: Read pp. xxxiv-iii and read and take notes on Chapter 1 p.3-29. This chapter covers basic information and the history of psychology. The material is pretty self-explanatory. Note any questions you have about the material. We will spend a day or two on this material which will be followed by a chapter test during the first week of school. Textbooks can be picked up from Mrs. Marinari before the end of school or in the main office during the summer. Assignment 2: Create a set of note cards on the top psychologists listed below. This will be due the Tuesday after Labor Day weekend. Cards should be 3x5 format. The top card should list your name in the upper left-hand corner and Top Psychologists in the center. Each of the psychologist cards should be numbered 1-50. The cards should be formatted as follows: FRONT OF CARD # card Person's full name BACK OF CARD Years alive (in upper right) Field: This should indicate what area of psychology the psychologist was most interested in. Contributions: This should detail (succinctly) what the major contributions/ideas/studies of the psychologist. Source: Source information of where you found your information *Avoid wikipedia *Must be handwritten and in pen *Feel free to color-code, your brain likes it-just be consistent!! Top 50 Psychologists for your cards 1. -

![Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James Mckeen Cattell (1928)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6838/early-psychological-laboratories-1-james-mckeen-cattell-1928-936838.webp)

Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James Mckeen Cattell (1928)

Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James McKeen Cattell (1928) Classics in the History of Psychology An internet resource developed by Christopher D. Green York University, Toronto, Ontario ISSN 1492-3173 Early Psychological Laboratories [1] James McKeen Cattell (1928) First published in Science, 67, 543- 548. Posted August 2000 Laboratories for research and teaching in the sciences are of comparatively recent origin. They may be regarded as part of the industrial revolution, for there is a close parallel in causes and effects between the development of the factory system and of scientific laboratories. The industrial revolution began with the exploitation by machinery of coal and iron in England; it may perhaps be dated from the use of the steam engine of Watts in the coal mines of Cornwall about a hundred and fifty years ago. The laboratory had its origin fifty years later in Germany as part of the scientific renaissance following the Napoleonic wars. The University of Berlin was founded by Wilhelm von Humboldt and Frederich William III in 1810. The first laboratory of chemistry was opened by Justus von Liebig at Giessen in 1824. This was followed by similar laboratories at Göttingen under Wöhler in 1836, at Marburg under Bunsen in 1840, and at Leipzig under Erdmann in 1843. The first English laboratory was the College of Chemistry, now part of the Imperial College of Science and Technology of the University of London, which was opened in 1845 by von Hoffmann, brought from Germany by Prince Albert. Benjamin Silliman founded at Yale University the first American laboratory for the teaching of chemistry. -

Illusion and Well-Being: a Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health

Psyehologlcal Bulletin Copyright 1988 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1988, Vol. 103, No. 2, 193-210 0033-2909/88/$00.75 Illusion and Well-Being: A Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health Shelley E. Taylor Jonathon D. Brown University of California, Los Angeles Southern Methodist University Many prominenttheorists have argued that accurate perceptions of the self, the world, and the future are essential for mental health. Yet considerable research evidence suggests that overly positive self- evaluations, exaggerated perceptions of control or mastery, and unrealistic optimism are characteris- tic of normal human thought. Moreover, these illusions appear to promote other criteria of mental health, including the ability to care about others, the ability to be happy or contented, and the ability to engage in productive and creative work. These strategies may succeed, in large part, because both the social world and cognitive-processingmechanisms impose filters on incoming information that distort it in a positive direction; negativeinformation may be isolated and represented in as unthreat- ening a manner as possible. These positive illusions may be especially useful when an individual receives negative feedback or is otherwise threatened and may be especially adaptive under these circumstances. Decades of psychological wisdom have established contact dox: How can positive misperceptions of one's self and the envi- with reality as a hallmark of mental health. In this view, the ronment be adaptive when accurate information processing wcU-adjusted person is thought to engage in accurate reality seems to be essential for learning and successful functioning in testing,whereas the individual whose vision is clouded by illu- the world? Our primary goal is to weave a theoretical context sion is regarded as vulnerable to, ifnot already a victim of, men- for thinking about mental health. -

Psychology and Its History

2 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCING PSYCHOLOGY'S HISTORY • Distinguish between primary and secondary sources of historical information and describe the kinds of primary source information typically found by historians in archives • Explain how the process of doing history can produce some degree of confidence that truth has been attained PSYCHOLOGY AND ITS HISTORY One hundred is a nice round number and a one-hundredth anniversary is ample cause for celebration. In recent years, psychologists with a sense of history have celebrated often. The festivities began back in 1979, with the centennial of the founding of Wilhelm Wundt's laboratory at Leipzig, Germany. In 1992, the American Psychological Associ ation (APA) created a yearlong series of events to commemorate the centennial of its founding in G. Stanley Hall's study at Clark University on July 8, 1892. During the cen tennial year, historical articles appeared in all of the APA's journals and a special issue of American Psychologist focused on history; several books dealing with APA's history were commissioned (e.g., Evans, Sexton, & Cadwallader, 1992); regional conventions had historical themes; and the annual convention in Washington featured events ranging from the usual symposia and invited addresses on history to a fancy dress ball at Union Station featuring period (1892) costumes and a huge APA birthday cake. Interest in psychology's history has not been limited to centennial celebrations, of course. Histories of psychology were written soon after psychology itself appeared on the academic scene (e.g., Baldwin, 1913), and at least two of psychology's most famous books, E. G. -

Organizing Knowledge and Behavior at Yale's Institute of Human Relations Author(S): J

Organizing Knowledge and Behavior at Yale's Institute of Human Relations Author(s): J. G. Morawski Source: Isis, Vol. 77, No. 2 (Jun., 1986), pp. 219-242 Published by: University of Chicago Press on behalf of History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/232650 Accessed: 22-12-2015 00:42 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. History of Science Society and University of Chicago Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.133.6.95 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 00:42:52 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Organizing Knowledge and Behavior at Yale's Institute of Human Relations By J. G. Morawski* IN 1929 JAMES ANGELL, president of Yale, announced plans for a unique teaching and research center for those fields "directly concerned with the problems of man's individual and group conduct. The purpose is to correlate knowledge and coordinate technique in related fields that greater progress may be made in the understanding of human life. The time has certainly come once again to attempt a fruitful synthesis of knowledge." The New York Times described the experiment as dismantling the disciplinary "Great Wall of China" and compared it with the Renaissance transformation of knowledge.1 The Insti- tute of Human Relations (IHR), as the center was named, received over $4.5 million from the Rockefeller Foundation for its first decade of operation. -

Psychologists and Physicians in the Borderlands of Science, 1900-1942

PSYCHOLOGISTS AND PHYSICIANS IN THE BORDERLANDS OF SCIENCE, 1900-1942 By WADE EDWARD PICKREN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1995 For my mother: WILLIE MERLE PICKREN, and in memoriam, BILL PICKREN, You taught me to love and work. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deepest gratitude to the chairman of my dissertation committee, Donald A. Dewsbury. Dr. Dewsbury has, from the beginning of this long project, been a model of encouragement, kindness, and unfailing generosity. He has shared his time, his great breadth of learning, his editorial ability, and his materials with me. My understanding of the history of psychology has been greatly deepened by our conversations. I also wish to acknowledge that Dr. Dewsbury has helped me to understand that data is a plural! Dr. Wilse B. Webb has also stimulated much thought in me about what I was doing and where I was going with my ideas. Although I did not avail myself of his wisdom as oft as I would have liked, his voice and his sharp eye were always with me. I hope that, in the future, time will allow me a greater opportunity to benefit from his great knowledge and experience. Both near at hand and from afar, Dr. Toby Appel has blessed me with the keenness of her insight . Her acceptance and friendly corrections of my halting efforts to write history have been much appreciated. One of my most pleasant memories of this experience is that of sitting at a table at iii Cafe Gardens talking about the history of biology or psychology, while hoping to hear some Van Morrison on the house music system. -

John Watson Is to Introspectionism As James Berlin Is to Expressivism (And Other Analogies You Won't Find on the Sat)

JOHN WATSON IS TO INTROSPECTIONISM AS JAMES BERLIN IS TO EXPRESSIVISM (AND OTHER ANALOGIES YOU WON’T FIND ON THE SAT) Maja Wilson I was in the Yale archives for the first time, reading the correspondence of early behaviorists John B. Watson and Robert M. Yerkes, and I couldn’t stop sneezing. A venerable looking scholar next to me, inspecting ancient manu- scripts with a magnifying glass, moved to the back of the room. Apparently, I was allergic to history. My very present problems had brought me to the archives: as a high school teacher, I had felt oppressed by the system of high stakes standardized testing mandated by No Child Left Behind (NCLB). The stated intent of NCLB was to promote equity, but the effects of testing seemed to be quite the opposite. Despite the modern rhetoric of equity associated with testing, I wondered if the original intent behind the creation of standardized tests foreshadowed the disastrous effects I saw playing out in schools. I knew that the first large scale standardized test in the United States—the Army Alpha Test (AAT)—had been created by eugenicists and used to promote their causes. Robert M. Yerkes, an avowed eugenicist, had helped create and administer the AAT during both World Wars. His assistant, Carl Brigham, pub- lished A Study of American Intelligence in 1923, in which he argued for “selective breeding” to preserve the integrity of the “Nordic race.” The AAT had revealed, according to Brigham, that southern and eastern Europeans had scored lowest on the test. Brigham’s book fueled growing anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States, and was used by Harry Laughlin, appointed by a House committee as an “expert eugenics agent,” to propose and pass the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924, which targeted eastern and southern Europeans. -

Points of View in the Modern History of Psychology

Points of View in the Modern History of Psychology Edited by Claude E. Buxton Department of Psychology Yale University New Haven, Connecticut 1985 ACADEMIC PRESS, INC. (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers) Orlando San Diego New York London Toronto Montreal Sydney Tokyo Passages from the following are reprinted by permission of the publishers: Newell, Α., Duncker on Thinking, in S. Koch & D. Leary (Eds.), A Century of Psychology as Science. Copyright 1985 by McGraw-Hill. Neisser, U., Cognitive Psychology. © 1967 by Prentice-Hall. COPYRIGHT © 1985 BY ACADEMIC PRESS, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPY, RECORDING, OR ANY INFORMATION STORAGE AND RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. ACADEMIC PRESS, INC. Orlando, Florida 32887 United Kingdom Edition published by ACADEMIC PRESS INC. (LONDON) LTD. 24-28 Oval Road, London NW1 7DX LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Main entry under title: Points of view in the modern history of psychology. Includes indexes. 1. Psychology— History. I. Buxton, Claude E. BF81.P57 1985 150\9 85-4010 ISBN 0-12-148510-2 (alk. paper) PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 85 86 87 88 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contributors Numbers in parentheses indicate the pages on which the authors' contributions begin. Mitchell G. Ash (295), Department of History, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 William Bevan (259), John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Chicago, Illinois 60603 Arthur L. Blumenthal (19, 51), Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts at Boston, Boston, Massachusetts 02125 Claude E. -

Building a “Cross-Roads Discipline” at Mcgill University: a History of Early Experimental Psychology in Postwar Canada

BUILDING A “CROSS-ROADS DISCIPLINE” AT MCGILL UNIVERSITY: A HISTORY OF EARLY EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY IN POSTWAR CANADA ERIC OOSENBRUG A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Psychology. Graduate Program in Psychology York University Toronto, Ontario October 2020 © Eric Oosenbrug, 2020 Abstract This dissertation presents an account of the development of psychology at McGill University from the late nineteenth century through to the early 1960s. The department of psychology at McGill represents an alternative to the traditional American-centered narrative of the cognitive revolution and later emergence of the neurosciences. In the years following World War II, a series of psychological experiments established McGill as among the foremost departments of psychology in North America. This thesis is an institutional history that reconstructs the origins, evolution, and dramatic rise of McGill as a major center for psychological research. The experiments conducted in the early 1950s, in the areas of sensory restriction, motivation, and pain psychology, were transformative in their scope and reach. Central to this story is Donald O. Hebb, author of The Organization of Behavior (1949), who arrived at McGill in 1947 to find the charred remains of a department. I argue that the kind of psychology Hebb established at McGill was different from most departments in North America; this is developed through a number of interwoven storylines focused on the understanding of a particular character of McGill psychology - a distinctive “psychological style” - and its broader historical importance for Canadian psychology, for North American psychology, and for psychology across the globe. -

Major Theories & Research Studies in Psychology

Major Theorists & Research Studies in Psychology From Joe Cravens, Dr. Phillips High School Rene Descartes: Dualism (mind and body are separate entities) John Locke: Tabula Rasa Theory (you were born a blank slate) Wilhelm Wundt: Father of modern psychology / introspection to study structuralism / selective attention / voluntarism = we control our attention, which in turn effects other psychological processes (memory, thought, perceptions) William James: America’s first psychologist / first psych textbook / functionalism Ivan Pavlov: Dogs and the salivary response / classical conditioning / Does his name ring a bell? Psychoanalytic / Psychodynamic Sigmund Freud: This is your unconscious not speaking to you / Id, Ego, Superego, stages of psychosexual development; oral, anal, phallic, latent, and genital / libido / transference Alfred Adler: Are you compensating for your inferiority complex? / Birth order / proposed that people are motivated more by feelings of inferiority than sexual instincts / are you ‘compensating’ for something? Anna Freud: Are your Ego Defense mechanisms working? Hermann Rorschach: Inkblots as projective tests Karen Horney: Feminist’s perspective with womb envy Henry Murray: Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) / the need for achievement Carl Gustav Jung: collective unconscious / mandala / archetypes / rational individuals – are people who regulate their actions by the psychological functions of thinking and feeling / irrational individuals are people who base their actions on perceptions, either through the senses (sensation) or through unconscious processes (intuition). Anima = female archetype as expressed in the male personality, animus = male archetype as expressed in the female personality. Introverts vs. extraverts. Erik Erikson: The stages of Psychosocial Development / adolescent identity crisis / lifespan development James Marcia: Identity Status (based on the work of Erikson) Identity Diffusion – the adolescent has not yet experienced a crisis or made any commitments. -

HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY: VOLUME 1, HISTORY of PSYCHOLOGY

HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY: VOLUME 1, HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY Donald K. Freedheim Irving B. Weiner John Wiley & Sons, Inc. HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY VOLUME 1 HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY Donald K. Freedheim Volume Editor Irving B. Weiner Editor-in-Chief John Wiley & Sons, Inc. This book is printed on acid-free paper. ➇ Copyright © 2003 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials.