Psychologists and Physicians in the Borderlands of Science, 1900-1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Introspectionism' and the Mythical Origins of Scientific Psychology

Consciousness and Cognition Consciousness and Cognition 15 (2006) 634–654 www.elsevier.com/locate/concog ‘Introspectionism’ and the mythical origins of scientific psychology Alan Costall Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Hampshire PO1 2DY, UK Received 1 May 2006 Abstract According to the majority of the textbooks, the history of modern, scientific psychology can be tidily encapsulated in the following three stages. Scientific psychology began with a commitment to the study of mind, but based on the method of introspection. Watson rejected introspectionism as both unreliable and effete, and redefined psychology, instead, as the science of behaviour. The cognitive revolution, in turn, replaced the mind as the subject of study, and rejected both behaviourism and a reliance on introspection. This paper argues that all three stages of this history are largely mythical. Introspectionism was never a dominant movement within modern psychology, and the method of introspection never went away. Furthermore, this version of psychology’s history obscures some deep conceptual problems, not least surrounding the modern conception of ‘‘behaviour,’’ that continues to make the scientific study of consciousness seem so weird. Ó 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Introspection; Introspectionism; Behaviourism; Dualism; Watson; Wundt 1. Introduction Probably the most immediate result of the acceptance of the behaviorist’s view will be the elimination of self-observation and of the introspective reports resulting from such a method. (Watson, 1913b, p. 428). The problem of consciousness occupies an analogous position for cognitive psychology as the prob- lem of language behavior does for behaviorism, namely, an unsolved anomaly within the domain of an approach. -

Psychological Bulletin

Vol. 19, No. 8 August, 1922 THE PSYCHOLOGICAL BULLETIN CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY— 1916-1921 By COLEMAN R. GRIFFITH University of Illinois Contributions to the history of psychology since 1915 fall nat- urally into two groups. There are, on the one hand, the systematic and the experimental studies which have made the science six years older. There are, on the other hand, the historical and biographical notes and the large and searching retrospections which relate con- temporary psychology to earlier stages in the development of the science. It is to an enumeration of these contributions that the present paper is devoted. We cannot, of course, comment in detail upon the character of contemporary psychology, for an historian, speaking of his own times is like the Hawaiian surf-rider who seeks to judge the incoming tide from his experiences while riding a single wave; but it is possible to get a certain amount of information about the current trend of a science by considering events of various kinds which reflect or which have, presumably, influenced its general course. These events taken in conjunction with what appear, at the present moment, to be outstanding experimental and systematic studies may give a suggestion of the history of the last few years. In psychology, as well as in many other sciences, the most important event, during the period under survey, was the World War. The science of psychology was, as all know, well on the way toward complete mobilization for military purposes when the war ended. Since many of the consequences of this reorganization have not yet appeared, a detailed account of this aspect of the period must fall to a future historian. -

ICS18 - Study Questions

ICS18 - study questions January 23, 2019 1. What is the broad and what is the narrow notion of cognition? 2. What is representation? Enumenrate examples of representations considerd within different disciplines (cog. psy- chology, neuroscience, AI) and show that they fulfill the definitional requirements 3. Enumerate and characterize briefly key cognitive disciplines 4. Key theses and principles of associationism 5. How to explain a mind: pure vs mixed associationism 6. A mind according to behaviorists 7. Why is behaviorism considered “the scientific psychology”? 8. Why behaviorism (as a theory of mind) was rejected? 9. Find the elements of behaviorism within contemporary cognitive theory of mind (either symbolic or connectionist) 10. Describe Turing Machine as a computational device 11. What is computation? (remember the roll of toilet paper...) 12. The idea of a mind as a “logic machine” (McCulloch, Pitts) 13. What features does a McCulloch-Pitts neuron have? 14. What is the main difference between a McC-P neuron and a perceptron? 15. What is a model? (cf. Kenneth Craik&Minsky) 16. What are the assumptions of phrenology? 17. Localizationist view on a brain (Gall, Spurzheim) 18. Holistic approaches to human brain 19. What does it mean that some part of our body has a “topographic representation” in the brain? 20. The consequences of Broca’s and Wernicke’s discoveries for a cognitive view on a brain 21. What is Brodmann famous for? 22. What did Golgi invent? What consequences had his discovery? 23. Describe Cajal’s discoveries and their influence on neuroscience 24. The key aassumptions of the “neuron doctrine” (Cajal) 25. -

Bibliotheca Sacra

Critical Noles. [Jan. ARTICLE X. CRITICAL NOTES. ROYCE'S "CONCEPTION OF GOD.") THIS work is a report of a discussion held before the Philosophical Union of the University of California in 1895. It coittains the leading address of the symposium by Professor Royce; remarks, critical and con structive, by the other participants in the discussion; and finally a sup plemental essay by Professor Royce in which he develops more thor oughly his central doctrine, and replies to his critics. It is apparent, from Professor Royce's introductory remarks, that the Philosophical Union of the University has beeu studying his work, "The Religious Aspect of Philosophy." .. Were there time, I should be glad indeed if I were able to throw any light 011 that little book. But my time is short. The great problems of philosophy are pressing. It is the death of your philosophizing if you come to believe anything merely be cause you have once maintained it. Let us lay aside, then, both text and tradition, and come face to face with ollr philosophical problem it self" (pp. 5, 6). This seems to breathe a spirit of admirable candor; but if, as we shall find later, the conclusions of Royce's present discussion are utterly irreconcilable with his results in .. The Religious Aspect," it would seem more candid, and also a saving of time, at least for the stu dents of the Philosophical Union, to recognize and deal thoroughly with this fact at the outset. In seeking a philosophical conception of God, Royce begins with the idea of an Omniscient Being. -

Freud: Memory and the Metapsychological Witch

Freud: Memory and the Metapsychological Witch Manuel Batsch Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College London 2015 I, Manuel Batsch confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisors, Juliet Mitchell and Liz Allison for their excellent guidance and generous encouragement during this project. Thanks to their benevolent attention and intelligent advice, I was able to construct and structure my research question. Our supervision meetings were crucial steps in the writing of my thesis and they also remain in my memory as transformative existential moments. I was impressed by the accuracy with which they read and corrected my drafts, a process from which I learnt a great deal. Psychoanalysis and Feminism is an important book in my inner library and often, when I feel threatened by a kind of intellectual inertia, I just have to reread some of its passages to regain a pleasure for thoughts. The seminars and supervisions with Juliet Mitchell have always triggered the same pleasure and inspired in me a form of bravery in thinking. I have been working under the supervision of Liz Allison since my MSc dissertation and throughout these years she has given me the confidence to compose academic work in English. Amongst many other things, I owe to her my introduction to a completely new reading of Derrida. Our Bion reading group was also extremely helpful and had a significant impact on my understanding of metapsychology after Freud. -

Radio-Electronics in Education

RADIO ELECTRONICS Published by Department of Information RADIO CORPORATION OF AMERICA 30 ROCKEFELLER PLAZA, NEW YORK, N. Y. FOREWORD 1 1 is booklet presents briefly the various types of aid which radio, both as a science and as a system of communication, renders to the cause of education. DI Education is as old as civilization itself; radio is one of civili- zation's newest products. It is therefore too early to appraise the ultimate extent or influence of their relationship. Enough has already been accomplished, however, both in the field of broadcasting and in the use of new educational techniques made possible by radio research, to prove that the importance of radio in the educational field is profound and far-reaching. New developments in radio and electronics, such as televi- sion and the electron microscope, are of the utmost significance to the future of education. It may be argued that the future of education is of slight interest when civilization is locked in a life-and-death struggle with forces which seek to destroy it. On the contrary, I believe it is a subject of major importance at this time. For the civilization of free men and women will triumph in this war, and the vital need for wise, courageous leadership will be more insistent in the post-war generation than ever before in historv. The education of both adults and children — and of the many, not the few — will stronglv influence the choice of poli- cies and of leaders capable of establishing and maintaining a better world for all humanity. -

The Hiring of James Mark Baldwin and James Gibson Hume at Toronto in 1889

History of Psychology Copyright 2004 by the Educational Publishing Foundation 2004, Vol. 7, No. 2, 130–153 1093-4510/04/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/1093-4510.7.2.130 THE HIRING OF JAMES MARK BALDWIN AND JAMES GIBSON HUME AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO IN 1889 Christopher D. Green York University In 1889, George Paxton Young, the University of Toronto’s philosophy professor, passed away suddenly while in the midst of a public debate over the merits of hiring Canadians in preference to American and British applicants for faculty positions. As a result, the process of replacing Young turned into a continuation of that argument, becoming quite vociferous and involving the popular press and the Ontario gov- ernment. This article examines the intellectual, political, and personal dynamics at work in the battle over Young’s replacement and its eventual resolution. The outcome would have an impact on both the Canadian intellectual scene and the development of experimental psychology in North America. In 1889 the University of Toronto was looking to hire a new professor of philosophy. The normally straightforward process of making a university appoint- ment, however, rapidly descended into an unseemly public battle involving not just university administrators, but also the highest levels of the Ontario govern- ment, the popular press, and the population of the city at large. The debate was not pitched solely, or even primarily, at the level of intellectual issues, but became intertwined with contentious popular questions of nationalism, religion, and the proper place of science in public education. The impact of the choice ultimately made would reverberate not only through the university and through Canada’s broader educational establishment for decades to come but, because it involved James Mark Baldwin—a man in the process of becoming one of the most prominent figures in the study of the mind—it also rippled through the nascent discipline of experimental psychology, just then gathering steam in the United States of America. -

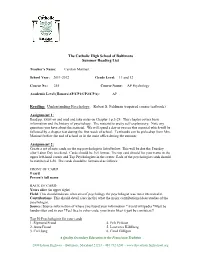

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Reading

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Teacher’s Name: Carolyn Marinari School Year: 2011-2012______________ Grade Level: 11 and 12 Course No.: 255 Course Name: AP Psychology Academic Level (Honors/AP/CP1/CP2/CPA): AP Reading: Understanding Psychology, Robert S. Feldman (required course textbook) Assignment 1: Read pp. xxxiv-iii and read and take notes on Chapter 1 p.3-29. This chapter covers basic information and the history of psychology. The material is pretty self-explanatory. Note any questions you have about the material. We will spend a day or two on this material which will be followed by a chapter test during the first week of school. Textbooks can be picked up from Mrs. Marinari before the end of school or in the main office during the summer. Assignment 2: Create a set of note cards on the top psychologists listed below. This will be due the Tuesday after Labor Day weekend. Cards should be 3x5 format. The top card should list your name in the upper left-hand corner and Top Psychologists in the center. Each of the psychologist cards should be numbered 1-50. The cards should be formatted as follows: FRONT OF CARD # card Person's full name BACK OF CARD Years alive (in upper right) Field: This should indicate what area of psychology the psychologist was most interested in. Contributions: This should detail (succinctly) what the major contributions/ideas/studies of the psychologist. Source: Source information of where you found your information *Avoid wikipedia *Must be handwritten and in pen *Feel free to color-code, your brain likes it-just be consistent!! Top 50 Psychologists for your cards 1. -

Raymond Dodge

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES R A Y M O N D D ODGE 1871—1942 A Biographical Memoir by W A L T E R R . M ILES Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1956 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. RAYMOND DODGE 1871-1942 BY WALTER R. MILES N HIS FRESHMAN YEAR at Williams College, Raymond Dodge kept I a diary. Its early entries reflect a sensitive, meditative boy, rather lonesome and homesick, finding his chief solace in thinking about the sermon which President Carter had preached the first Sunday of the school year. But he showed himself capable of "adaptive adjust- ment," to use a phrase of his mature years, and at the end of a month was able to say, "Everything is fine." His mother had visited him, his first examination in Greek had not turned out as badly as feared, and he had decided to stay at the college and work in the library during the Thanksgiving vacation. Of this vacation period he recorded, "I stayed here all the time, wrote my editorial for the Weekly, worked up my debate, and read 'Wallace on Darwinism' and 'A naturalist's voyage around the world' by Darwin. I wanted to get a deeper in- sight into Darwin's theories and didn't know when I could do it if not during this vacation." Turning this diary over and beginning at the back, one finds the note which he wrote after reading Darwin's "Voyage." It gives the Williams College Library accession number, title, author, and then "p. -

Influência De Jerome Bruner Na Teoria Da Aprendizagem Musical De Edwin Gordon

INFLUÊNCIA DE JEROME BRUNER NA TEORIA DA APRENDIZAGEM MUSICAL DE EDWIN GORDON Ricardo Dourado Freire [email protected] Departamento de Música da Universidade de Brasília Verônica Gomes Archanjo de Oliveira Silva [email protected] Resumo Neste artigo é realizadas uma análise teórica dos Níveis e Subníveis de Competências musicais estabelecidos por Edwin Gordon (1997) a partir dos fundamentos teóricos para elaboração de teorias de aprendizagem propostos por Jerome Bruner (1965). A compreen- são das idéias de Bruner serve para elucidar aspectos estruturais da Teoria da Aprendiza- gem Musical de Gordon e permite o esclarecimento de procedimentos e propostas de Gor- don dentro da perspectiva da psicologia cognitiva. Palavras-chave : Aprendizagem Musical, Jerome Bruner, Edwin Gordon. O pesquisador estadunidense Edwin Gordon desenvolveu nos últimos 50 anos uma extensa obra nas áreas de psicologia da música e educação musical. Sua trajetória acadê- mica passa pelo doutoramento na University of Iowa (1958), atuação como docente na University of Iowa, 1958-1973, na State University of New York at Buffalo (SUNY- Buf- falo), 1973-1979, até sua permanência na Carl Seashore Chair for Research in Music Edu- cation da Temple University entre 1979 e sua aposentadoria em 1997. Durante sua trajetó- ria acadêmica publicou 94 livros, com traduções em português, italiano e lituano, além de ter orientado aproximadamente 40 dissertações de doutorado. Sua carreira como pesquisa- dor nas áreas de psicologia da música e educação musical influenciaram toda uma corrente de pesquisa na linha de música. Nesta abordagem, os processos cognitivo-musicais são observados a partir de uma estrutura seqüencial de desenvolvimento que aplica à área de música a proposta teórica de Jerome Bruner publicada em Toward a Theory of Instruction (1965) Nos primeiros anos de pesquisas na Univeristy of Iowa, Gordon inicia um profundo estudo sobre a aptidão musical e os processos que influenciam o desenvolvimento musical do indivíduo baseado nos trabalhos de Seashore e Drake. -

Genealogy of Hugh Stewart and Descendants

Genealogy of Hugh Stewart and Descendants COMPILED BY FRANCENIA STEWART WHITE ESTHER STEWART HUNT EMMA STEWART LYMAN 1892-1895· 1912 · COLUMBUS, OHIO THE F. J. HEER PRINTING COMPANY 1914 ANCESTRAL PLAQUE. 1Jn .fflemnry nf 1.Eatfler. To whose Devotion and Love of family we are indebted for much of the material, these pages are dedicated as fulfilling her loyal thought and desire of years. F. S. W. E. S. L. "They are not long, the weeping and the laughter, Love and desire and hate, I think they have no portion in us after We pass the Gate ! " -Dawson. ERRATA. 'f!here are several names that were unintentionally omitted in the proper places, but have been numbered in such a way as to indicate their positions in their respective families. EXPLANATION OF ABBREVIATIONS. b - born. m - married. d - died. In tracing the generations we ·have adopted the simple plan of be ginning with Hugh Stewart, the earliest family name of which we have knowledge, calling him Hugh1 (frrst generation). Each child of his is, in turn, following name, 2 (2nd generation) ; each grandchild, 3 (3rd gen eration) ; each great grandchild 4 ( 4th gene,ration) ; each great. great grandchild is 5 ( 5th generation), etc. This is the key that will enable anyone quickly to trace each person without trouble, but be sure to get it fixed in your mind, at the start. ·:,:,~. ~ ELIZABETH RoxnuRGH-S MITH. ( Lady Dalrymple.) Badge-Oak. Slogan or vVar-cry- Creag-an-Sgairbh. (A. rock in April.) _--\rms - Or, a Fesse cheguy. Ar.. and Az .. surmounted of a bend engr., Gu., within a double tressure, flory-counter-flory, of the last. -

History of Psychology

The Psych 101 Series James C. Kaufman, PhD, Series Editor Department of Educational Psychology University of Connecticut David C. Devonis, PhD, received his doctorate in the history of psychology from the University of New Hampshire’s erstwhile pro- gram in that subject in 1989 with a thesis on the history of conscious pleasure in modern American psychology. Since then he has taught vir- tually every course in the psychology curriculum in his academic odys- sey from the University of Redlands in Redlands, California, and the now-closed Teikyo Marycrest University (formerly Marycrest College in Davenport, Iowa) to—for the past 17 years—Graceland University in Lamoni, Iowa, alma mater of Bruce Jenner and, more famously for the history of psychology, of Noble H. Kelly (1901–1997), eminent con- tributor to psychology’s infrastructure through his many years of ser- vice to the American Board of Examiners in Professional Psychology. Dr. Devonis has been a member of Cheiron: The International Society for the History of Behavioral and Social Sciences since 1990, a con- tributor to many of its activities, and its treasurer for the past 10 years. Currently he is on the editorial board of the American Psychological Association journal History of Psychology and is, with Wade Pickren, coeditor and compiler of the online bibliography History of Psychology in the Oxford Bibliographies Online series. History of Psychology 101 David C. Devonis, PhD Copyright © 2014 Springer Publishing Company, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Springer Publishing Company, LLC, or authorization through payment of the appropriate fees to the Copyright Clearance Cen- ter, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, [email protected] or on the Web at www.copyright.com.