An Inklings Bibliography (50)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2

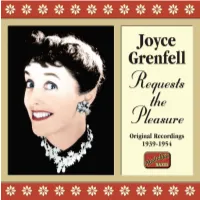

120860bk Joyce:MASTER BOOK 3+3 NEW 6/10/07 2:58 PM Page 2 1. I’m Going To See You Today 2:16 7. Mad About The Boy 5:08 12. The Music’s Message 3:05 16. Folk Song (A Song Of The Weather) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) (Noël Coward) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 1:29 With Richard Addinsell, piano With Mantovani & His Orchestra; Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Michael Flanders-Donald Swann) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9899-5 introduced by Noël Coward 13. Understanding Mother 3:10 With piano Recorded 17 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #4, (Joyce Grenfell) 17. Shirley’s Girl Friend 4:46 Towers of London, 1947–48 2. There Is Nothing New To Tell You 3:29 14. Three Brothers 2:57 (Joyce Grenfell) (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 8. Children Of The Ritz 3:59 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) 18. Hostess; Farewell 3:03 With Richard Addinsell, piano (Noël Coward) Orchestra conducted by William Blezard (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) HMV B 9295, 0EA 9900-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Recorded 3 September 1942 Noël Coward Programme #12, 15. Palais Dancers 3:13 Towers of London, 1947–48 (Joyce Grenfell–Richard Addinsell) Tracks 12–18 from 3. Useful And Acceptable Gifts Orchestra conducted by William Blezard Joyce Grenfell Requests the Pleasure (An Institute Lecture Demonstration) 3:05 9. We Must All Be Very Kind To Auntie Philips BBL 7004; recorded 1954 From The Little Revue Jessie 3:28 (Joyce Grenfell) (Noël Coward) All selections recorded in London • Tracks 5–9 previously unissued commercially HMV B 8930, 0EA 7852-1 With Mantovani & His Orchestra Transfers and Production: David Lennick • Digital Restoration:Alan Bunting Recorded 11 May 1939 (3:04) Noël Coward Programme #13, Original records from the collections of David Lennick and CBC Radio, Toronto 4. -

Croydon Friends Newsletter

CROYDON FRIENDS NEWSLETTER January 2016 Dear Friends, Our newsletter this month gathers together news of Friends sent in on Christmas cards or in letters and emails, which reflect our Meeting as a family community It also reflects our lives within the Quaker world, within our community, our Area Meeting, and our Religious Society as a whole. Gillian Turner “My grace is sufficient for thee”, 2 Corinthians 12:9 At this time of year, we are encouraged to believe that in order to achieve happiness and peace we should draw up a list of New Year’s Resolutions. As if by magic we will become fitter and stronger, more intelligent, give up a creeping sugar addiction, be much nicer and more helpful to Ffriends and family etc. Each year I find the list easier and easier to compile as one “benefit” of the ageing process seems to be a heightened awareness of my shortcomings. When designing advertising campaigns, the toxic bombs of guilt and shame are sometimes used in order to encourage our mostly fruitless attempts at so-called self-improvement. Businesses know that resolutions made at this time of year invariably lead to the need to buy goods and services which purport to help us to achieve our targets. Exercise bikes, subscriptions to improving publications, gym memberships and cosmetics are often marketed as the means to realise our dreams. Of course, thinking about a few, well-chosen, specific and achievable ideas by which to either increase self-esteem and/or help our fellows is no bad thing and can be done at any time of the year, without the purchase of items which will end up in the back of a cupboard or drawer. -

Donald Swann Including Songs by Sydney Carter Sing Round the Year 18 CAROLS SELECTED and COMPOSED by Donald Swann Including Songs by Sydney Carter

Sing round the year 18 CAROLS SELECTED AND COMPOSED BY Donald Swann including songs by Sydney Carter Sing round the year 18 CAROLS SELECTED AND COMPOSED BY Donald Swann including songs by Sydney Carter P 1968 Move Records move.com.au onald Swann will forever be popularly known as the musical half of the comic song writing duo Flanders & Swann; but the quintessential Englishness of that satiric output belies his exoticD roots – Donald’s middle name, Ibrahím, is a clue. Donald was born in Llanelli on 30 Sept 1923 into a family of amateur musicians, both parents refugees from the Russian Revolution. His upbringing was one of Russian folk song and four-hand piano reductions of the Russian and European Romantics. Donald Swann and Michael Flanders had been performing their own songs at cast read-throughs and private parties for some years often, as they would say “at the drop of a hat”; they gradually honed their material as a double-act. Their show, titled AT THE DROP OF A HAT, opened on 31st December 1956 and was an overnight success. A sequel, AT THE DROP OF ANOTHER HAT, opened at Theatre Royal, Haymarket in London October 1963 for a long run before reverting to its previous title for performances in Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong. Over the next few years Donald compiled and performed hundreds of concerts; sometimes solo or often with different performers picked to explore the variety of his output. EXPLORATIONS ONE, with Sydney Carter, concentrated on words and music in a folk idiom. The show was later expanded, with the addition of Jeremy Taylor, into AN EVENING WITH CARTER, TAYLOR & SWANN which took folk music into mainstream theatres. -

Animal Songsbestiaries in English, French, & German

Acknowledgments I have had the pleasure of counting John Moriarty Websites: Animal Songs Bestiaries in English, French, & German among my friends for nearly 40 years and wish to Stephen Swanson, baritone thank him for his help in preparing this recording. www.stephenswansonbaritone.com One of the joys of working for a major research David Gompper, piano institution is having colleagues who are willing http://davidgompper.com/ and able to help when my personal expertise will not suffice. Thanks to Downing Thomas for his Producer: Stephen Swanson translations of the Renard poems in this booklet. Recording Engineer: Bruce Gigax —Stephen Swanson Assistant Engineer: Reed Wheeler Recording Location: Audio Recording Ciardi, John, An Alphabestiary, Philadelphia, Studio, Bentleyville, Ohio J. B. Lippincott, 1966. Recording Dates: August 2-4, 2011 Gompper, David, The Animals, Iowa City, Liner Notes: Marilyn Swanson Edzart Music Publications, 2009. Illustrations © 2012 by Claudia McGehee Ravel, Maurice, Songs, 1896-1914, Funded in part by a grant from edited by Arbie Orenstein, New York, Dover, 1990. the Arts & Humanities Initiative Reger, Max, Sämtliche Werke, Band 33, edited by at The University of Iowa, Fritz Stein, Wiesbaden, Breitkopf & Härtel, 1959. The University of Iowa School of Music, The Songs of Michael Flanders & Donald Swann, and The University of Iowa College of London, Elm Tree Books and St George’s Press, 1977. Liberal Arts and Sciences www.albanyrecords.com TROY1365 albany records u.s. 915 broadway, albany, ny 12207 tel: 518.436.8814 fax: 518.436.0643 albany records u.k. box 137, kendal, cumbria la8 0xd tel: 01539 824008 © 2012 albany records made in the usa ddd waRning: cOpyrighT subsisTs in all Recordings issued undeR This label. -

Flanders and Swann

FLANDERS AND SWANN On the 25th April we were treated to an interesting talk and musical extravaganza from Kevin Varty on the work and music of Michael Flanders and Donald Swann. The talk whilst giving the history of the duo, concentrated on the music and lyrics and demonstrated the different types of songs they were known for by playing some including I’m a Gnu and The Gasman Cometh. It was surprising how topical these songs still are! Flanders and Swann met early in life when they both attended Westminster school. This is where they started their collaboration on a school revue called “Go To It”, Flanders wrote the lyrics whilst Swann wrote the music. When they left school they went their separate ways until they met again after the war in Oxford. By this time Michael had contracted polio and was using a wheelchair. They started to perform their own songs at private parties and to small audiences and were persuaded to open their own revue on New Year’s Eve in 1956 at the New Lindsey, a small theatre in Notting Hill. They called the show ‘At the Drop of a Hat’ - a musical revue that had no scenery, two grey curtains, a piano, a man in a wheelchair and a cast that had hired their suits from Moss Bros. This format was the one they were to continue to use until they stopped performing together in 1967. At the Drop of a Hat was so successful that three weeks later it transferred to the Fortune Theatre in the West End where it ran for 759 performances and was followed by another revue At the Drop of Another Hat. -

Donald Swann

divine art DONALD SWANN - The Isles of Greece Lucinda Broadbridge, soprano Juliet Alderdice, mezzo-soprano Jeffrey Cresswell, tenor 25010 1 Casos Sonnet I Far, far off in a distant southern sea - Donald Swann (with Bill Skeat) [2.45] 25010 2 Samiotissa - Lucinda Broadbridge, Juliet Alderdice, Jeffrey Cresswell [1.31] 3 Miranda - Lucinda Broadbridge [3.04] 4 Pes Mou ti - Jeffrey Cresswell [1.18] Tracks 2 - 20 (DDD) SWANN - The Isles of Greece - The SWANN 5 Casos Sonnet II I ve always feared the night before dawn - Juliet Alderdice [2.08] recorded at the Church 6 The Women of Souli - Lucinda Broadbridge, Juliet Alderdice [2.56] of St. Mary Magdalene, 7 Casiot Journey - Orchestral [3.26] London, 22/23 February 1996 8 The Favours - Lucinda Broadbridge, Jeffrey Cresswell [3.17] Producer: Brian Hunt 9 Casos Sonnet III With only a red night light for my pen - Jeffrey Cresswell [2.33] Engineers: Steven Evans Jonathan Mellor 10 Anatoli - Juliet Alderdice [5.17] Track 1 (ADD - 1991) 11 Nanourisma - Lucinda Broadbridge [3.53] Tracks 21-28 (ADD - 1986) 12 Casos Sonnet IV When shall I land on you, distant island - Lucinda Broadbridge [2.12] recorded by Donald Swann 13 Militsa - Juliet Alderdice, Lucinda Broadbridge, Jeffrey Cresswell [3.57] at Albert House, Battersea 14 Nikotsaras - Jeffrey Cresswell [3.32] Greek Language Coach: 15 Casos Sonnet V Casos, today I m writing you a letter - Juliet Alderdice [1.25] Robyn Sevastos 16 The Shepherdess - Jeffrey Cresswell [3.20] Music published by Thames Publishing 17 Idle Tears - Juliet Alderdice, Jeffrey Cresswell [5.13] Original sound recording 18 Casos Sonnet VI So far you re licking me, Casos, for real - Lucinda Broadbridge [2.36] made for the Donald Swann 19 The Isles of Greece - Juliet Alderdice [4.36] Estate. -

Michael Flanders and Donald Swann at the Drop of a Hat Mp3, Flac, Wma

Michael Flanders And Donald Swann At The Drop Of A Hat mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Non Music / Pop Album: At The Drop Of A Hat Country: US Released: 1957 Style: Comedy, Novelty MP3 version RAR size: 1682 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1982 mb WMA version RAR size: 1117 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 573 Other Formats: AIFF ASF MP1 VOC MP2 XM MP3 Tracklist A1 A Transport Of Delight A2 Song Of Reproduction A3 A Gnu A4 Design For Living A5 Je Suis Le Ténébreux Songs For Our Time A6.a Philological Waltz A6.b Satellite Moon A6.c A Happy Song B1 A Song Of The Weather B2 The Reluctant Cannibal B3 Greensleeves B4 Misalliance B5 Kokoraki - A Greek Song B6 Madeira, M' Dear? B7 Hippopotamus Credits Photography By – Angus McBean Piano – Donald Swann, Michael Flanders Notes Recorded during an actual performance at the Fortune Theatre, London Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Label, Side A): XEX.180 Matrix / Runout (Label, Side B): XEX.181 Matrix / Runout (Stamped Side A): XEX 180-D3 Matrix / Runout (Stamped Side B): XEX 181-D4 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Michael At The Drop Of A PMC 1033 Flanders And Hat (LP, Album, Parlophone PMC 1033 UK 1957 Donald Swann* Mono) Michael At The Drop Of A PMCO 1033 Flanders And Hat (LP, Album, Parlophone PMCO 1033 Australia 1956 Donald Swann* Mono) Michael At The Drop Of A PMC 1033 Flanders And Hat (LP, Album, Parlophone PMC 1033 UK Unknown Donald Swann* Mono, RP) Michael At The Drop Of A South PMCJ 1033 Flanders And Hat (LP, Album, Parlophone PMCJ 1033 1957 Africa Donald Swann* Mono) At The Drop Of A Michael Hat - An After Angel 35797 Flanders And 35797 US Unknown Dinner Farrago Records Donald Swann* (LP, Mono) Related Music albums to At The Drop Of A Hat by Michael Flanders And Donald Swann Joyce Grenfell - Requests The Pleasure The Chappaqua High School Kids - Sweet Leontine / A Happy Song The Crew-Cuts - Gum Drop / Song Of The Fool Michael Flanders And Donald Swann - At The Drop Of Another Hat T. -

Warra Warra DAVID MESHER San José State University

130 JASAL SPECIAL ISSUE 2007: SPECTRES, SCREENS, SHADOWS, MIRRORS The Spectrum of Spectral Colonisation in John Scott’s Warra Warra DAVID MESHER San José State University The cleverness of Laurie Duggan’s study of Australia as a Ghost Nation (2001) has less to do with its thesis than with the variety and insight provided by Duggan’s examples. Subtitled Imagined Space and Australian Visual Culture 1901-1939, Duggan’s text is involved with the artifacts of Australian modernism, pre-war culture, and the rise of technology in a way only suggested in his title. Duggan’s “ghost” is a cultural, not paranormal, phenomenon, in which “‘imagined’ spaces and ‘observed’ spaces may coexist within other ‘regulated’ spaces and an individual may inhabit all of them” (xxii). Australia, for Duggan, is a “‘ghost nation’ . not in the sense that it is the shadow of something that is dead, but in a visual sense of images which ghost each other; not as layers or levels but as a kind of parallax view which must exist in any slice of time, whose images shift about (against) each other within time” (xxiii). Duggan’s “ghost”, which provides a metaphor to deal with the series of culturally distinct realities simultaneously occupying the same space that is contemporary Australia, is therefore distinct from the colonial conception of Australian culture as a spot on the periphery attempting, culturally and in other ways, to duplicate (or “ghost”) the imperial center. Still, when his theories of Australia as a “ghost nation” lead, even indirectly, to a contemporary Australian ghost story such as John Scott’s novel Warra Warra (2003)—which describes the spectral re-colonisation of an Australian town by ghosts of the British passengers and crew of a jetliner blown out of the skies in a terrorist bombing—this seems less a misunderstanding than a further “ghosting” of Duggan’s own thesis. -

The Road Goes Ever On

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 A Swann's Song in Middle-earth: An Exploration of Donald Swann's "The Road Goes Ever On" and the Development of a System of Lyric Diction for Tolkien's Constructed, Elvish Languages Richard Garrett Leonberger Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Leonberger, Richard Garrett, "A Swann's Song in Middle-earth: An Exploration of Donald Swann's "The Road Goes Ever On" and the Development of a System of Lyric Diction for Tolkien's Constructed, Elvish Languages" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4323. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4323 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A SWANN’S SONG IN MIDDLE-EARTH: AN EXPLORATION OF DONALD SWANN’S THE ROAD GOES EVER ON AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF A SYSTEM OF LYRIC DICTION FOR TOLKIEN’S CONSTRUCTED, ELVISH LANGUAGES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Richard G. Leonberger B.M., Stephen F. Austin State University, 2010 M.M., Binghamton University, 2012 November 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many people across the world contributed time, energy, and support to me and to this project. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 2 – 8 March 2013

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 2 – 8 March 2013 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 02 MARCH 2013 Desperate to see an Everton football match, a boy turns to him First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2013. for help... SAT 13:15 John Mortimer - The Antisocial Behaviour of SAT 00:00 Haunted (b01qyswf) Written by Vincent McInerney. Horace Rumpole (b01r1b3c) The Grey Ones, by JB Priestley Read by Richard Tate. Rumpole on Trial A patient fears evil is at work in the shape of a sinister Producer: Michael Earley 4 Extra Debut. The magician of the Old Bailey at his conspiracy. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 1995. implacable best defending our ancient freedoms. Drama stars Will his psychiatrist be able to help? SAT 04:15 The Recall Man (b00kkdkk) Timothy West. JB Priestley's creepy tale dramatised by Patricia Mays. Stepping Out SAT 14:00 The Al Read Show (b0090v01) Patson ...... Tony Britton Dr Joe Aston feels threatened when a rival psychologist is hired From 6/2/1966 Dr Smith ...... Jack May. to investigate baffling attacks on women. Stars Jeremy Swift. The legendary Northern comic pokes fun at fireman and Producer: Derek Hoddinott SAT 05:00 Little Blighty on the Down (b007jxd2) hospitals. Director: Martin Williamson Series 2 Monologues and sketches presenting "life with the lid off". First broadcast on the BBC World Service in July 1983. Episode 4 With Susan Maughan, The Countrymen, and Woolf Phillips and SAT 00:30 James Follett - Earthsearch (b007jp2r) Troubles abound in the village boatyard and surgery - with a his Orchestra. Earthsearch II sleazy press. -

The Road Goes Ever on by Donald Swann and Other Works of Adventure

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU The Caine College of the Arts Music Program All Music Department Programs Archives 5-2-2017 Senior Recital- Benjamin Krutsch: The Road Goes Ever On by Donald Swann and other works of adventure Benjamin Krutsch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Krutsch, Benjamin, "Senior Recital- Benjamin Krutsch: The Road Goes Ever On by Donald Swann and other works of adventure" (2017). All Music Department Programs. 11. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/music_programs/11 This Student Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the The Caine College of the Arts Music Program Archives at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Music Department Programs by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 51Y j#¸ 4,Y o`N y2#P6R 6EÉ jiY1 - The Road Goes Ever On by Donald Swann and other works of adventure Benjamin Krutsch, tenor with Dallas Heaton, piano Tuesday, May 2, 2017 7:00 PM St. John’s Episcopal Church Logan, Utah j#¸ y~B 9r#È 1} 2iR2%È ,T o1E 1} 2`N y4% @ 1`BtÈ 41E ,T xr%5$ iU - @ 7`N2# x`N`V8 r$6R 5^ 2ÈP 5^ -PROGRAM- from Die schöne Müllerin ..................................................... Franz Schubert Das Wandern (1797 – 1828) Wohin? Halt! What’s Next? ............................................................................ Andrew Lippa from Big Fish: A New Broadway Musical (b. 1964) with Brad Summers, baritone L'invitation au voyage ............................................................. Henry Duparc (1848 – 1933) -INTERMISSION- The Road Goes Ever On ........................................................ -

The King's Singers Discography by Album Year

THE KING'S SINGERS DISCOGRAPHY BY ALBUM YEAR ALBUM TITLE TRACK NAME WORDS MUSIC ARRANGER Track KS personnel Other Where/when Producer Engineer Length Artists recorded 1971 BY APPOINTMENT The peanut vendor Sunshine, Gilbert, Simons Gordon Langford Nigel Perrin KS and GLT Shenandoah Trad. Trad. Gordon Langford Alastair Hume KS Enterprise Records Cherry ripe Trad. Trad. Alastair Thompson KS ENTM 501 Summertime George Gershwin Anthony Holt KS Time was Prado Gordon Langford Simon Carrington KS The Gordon Langford trio Scarborough Fair Trad. Paul Simon Brian Kay KS None but the lonely heart Tchaikowsky KS Linstead market Trad. Trad. Gordon Langford KS The oak and the ash Trad. Trad. Gordon Langford KS Wives and lovers Burt Bacharach KS Blow away the morning dew Trad. Trad. Gordon Langford KS The green leaves of summer Tiomkin KS What kind of things Ron Goodwin Ron Goodwin KS and GLT 1972 THE KING'S SINGERS She's leaving home Lennon/McCartney George Martin Nigel Perrin KS AIR Studios, George Martin Jack Clegg The windmills of your mind Michel Legrand Chris Walker Alastair Hume KS London I love you Samantha Jeremy Lubbock Alastair Thompson KS Columbia (EMI) Morning has broken Chris Walker Anthony Holt KS Apres un reve Joseph Horowitz Simon Carrington KS Watch me Ron Goodwin Brian Kay KS The game George Martin KS Building a wall Ron Goodwin KS My colouring book C. Bowers-Broadbent KS Ask yourself why R. Rodney Bennett KS Orange yellow ochre Chris Walker KS A taste of honey C. Bowers-Broadbent KS 1972 CAPTAIN NOAH AND Captain Noah and his floating zoo Michael Flanders Joseph Horowitz Joseph Horowitz Nigel Perrin KS, JH, DR, Kevin Daly Ian Churches HIS FLOATING ZOO Alastair Hume RJ Alastair Thompson Argo (Decca) ZDA 149 Anthony Holt Simon Carrington Joseph Horovitz (piano) Brian Kay Daryl Runswick (d.