NEPAL: Polmcal EVOLUTION in AHINDU MONARCHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Civil Society in Uncivil Places: Soft State and Regime Change in Nepal

48 About this Issue Recent Series Publications: Policy Studies 48 Policy Studies Policy This monograph analyzes the role of civil Policy Studies 47 society in the massive political mobilization Supporting Peace in Aceh: Development and upheavals of 2006 in Nepal that swept Agencies and International Involvement away King Gyanendra’s direct rule and dra- Patrick Barron, World Bank Indonesia matically altered the structure and character Adam Burke, London University of the Nepali state and politics. Although the opposition had become successful due to a Policy Studies 46 strategic alliance between the seven parlia- Peace Accords in Northeast India: mentary parties and the Maoist rebels, civil Journey over Milestones Places in Uncivil Society Civil society was catapulted into prominence dur- Swarna Rajagopalan, Political Analyst, ing the historic protests as a result of nation- Chennai, India al and international activities in opposition to the king’s government. This process offers Policy Studies 45 new insights into the role of civil society in The Karen Revolution in Burma: Civil Society in the developing world. Diverse Voices, Uncertain Ends By focusing on the momentous events of Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung, University of the nineteen-day general strike from April Massachusetts, Lowell 6–24, 2006, that brought down the 400- Uncivil Places: year-old Nepali royal dynasty, the study high- Policy Studies 44 lights the implications of civil society action Economy of the Conflict Region within the larger political arena involving con- in Sri Lanka: From Embargo to Repression ventional actors such as political parties, trade Soft State and Regime Muttukrishna Sarvananthan, Point Pedro unions, armed rebels, and foreign actors. -

All Change at Rasuwa Garhi Sam Cowan [email protected]

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 33 | Number 1 Article 14 Fall 2013 All Change at Rasuwa Garhi Sam Cowan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Cowan, Sam (2013) "All Change at Rasuwa Garhi," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 33: No. 1, Article 14. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol33/iss1/14 This Research Report is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Research Report | All Change at Rasuwa Garhi Sam Cowan From time immemorial, pilgrims, traders, artisans, and Kyirong to aid the transshipment of goods and to carry religious teachers going to Lhasa from Kathmandu had to out major trading on their own account. Jest records that decide between two main routes. One roughly followed as late as 1959 there were forty five Newar households in the line of the present road to Kodari, crossed the border Kyirong and forty in Kuti (Jest 1993). where Friendship Bridge is built and followed a steep trail The two routes were used for the invasion of Tibet in 1788 to Kuti (Tib. Nyalam). Loads were carried by porters up to and 1791 by the forces of the recently formed Gorkha this point but pack animals were used for the rest of the state under the direction of Bahadur Shah, which led to journey. -

A Case Study of Jana Andolan II in Nepal

Occasional Paper: Peace Building Series No.1 FutureGenerations Applied Community Graduate School Change and Conservation PeoPle’s ParticiPation in conflict transformation: a case study of Jana andolan II in nePal Bandita Sijapati Social Science Baha February 2009 Occasional Papers of the Future Generations Graduate School explore community-based approaches to social development, health, nature conservation, peace building, and governance. Faculty, alumni, and partner organizations present their field studies and applied research. www.future.edu People’s Participation in Conflict Transformation: A Case Study of Jana Andolan II in Nepal Rise from every village, rise from every settlement To change the face of this country, rise Those who have a pen in hand, bring your pen and rise Those who can play an instrument, bring your instrument and rise Those who have a tool in hand, bring your tool and rise Those who have nothing at all, bring your voice and rise.1 I. INTRODUCTION In April 2006, there was a country-wide people’s movement in Nepal, popularly known as the Jana Andolan II,2 against King Gyanendra’s direct rule3 following a 12-point understanding reached between the Seven Party Alliance4 and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), which was leading a communist insurgency against the state. The 19-day-long Jana Andolan II5 (People’s Movement II) ended direct rule by Gyanendra, forced him to return power to the reinstated parliament, and created a conducive environment for the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the government and the rebel Maoists in November 2006. The success of Jana Andolan II in thus ending the decade-long conflict that had affected all parts of the country has thus been hailed by many as being exemplary of the ways in which engaged citizenry and communities at the local level can have an impact on the resolution and transformation of violent conflict at the national level. -

Compliment to Surya Thapa Siddhi B Ranjitkar

Compliment To Surya Thapa Siddhi B Ranjitkar One of the personalities of the regressive force Surya Bahadur Thapa ultimately died at 87 on Wednesday, April 15, 2015. He was cremated on April 17, 2015 with the full state honor. The government even shut down its business for the state employees to mourn the demise of one of the corrupt politicians. I want him to have a better and progressive life in another world, and be an honorable and respectable human soul there unlike what he had been in this mundane world. He had been a tool of the regressive force. He contributed to shove democracy in a trashcan and put the country in the reverse gear in 1960. He helped to reverse the political development in 1981 again lengthening the life of the corrupt panchayat system. He had earned the reputation of being one of the most corrupt politicians during the 55 years of his political life. Shame on the government and the politicians that gave so much of honor to and respect for the man that had become part of the force that put the majority of the Nepalese in misery, poverty and destitute, and put Nepal into the shameful status of one of the impoverished countries in the world map. If the corrupt politicians were to get so much of honor and respect even after death why the politicians would need to be sincere and honest to the people. Shame on the Nepalese politicians, such a corrupt politician was lionized. On Friday, April 17, 2015, the government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal honored one of the most dishonest politicians of the Nepalese history on his untimely death. -

Speeches of Heads of the Nepalese Delegation to the Non-Aligned Movement (1961-2009)

Speeches of Heads of the Nepalese Delegation to the Non-Aligned Movement (1961-2009) Institute of Foreign Affairs, IFA Tripureshwor, Kathmandu 2011 NAM Statements Published By Institute of Foriegn Affairs (IFA) Kathmandu, Nepal Phone 977-1-4266954 977-1-4266955 Fax 977-1-4266956 E-mail [email protected] URL www.ifa.org.np ISBN 978-9937-8459-0-8 © Institute of Foriegn Affairs First Published IFA, April 2011 1000 pcs Printed at Heidel Press Pvt. Ltd. Dillibazar, Kathmandu, Nepal. 977-1-4439812, 2002346 Contents The Statements of the Nepalese Heads of State or Government of NAM from 1961-2009 1. His Majesty Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev First NAM Summit-1961, Belgrade ..........................................................1 2. His Majesty Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev Second Summit-1964, Cairo ....................................................................9 3. His Majesty Mahendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev Third Summit-1970, Lusaka ...................................................................17 4. His Majesty Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev Fourth Summit-1973, Algeria ................................................................24 5. His Majesty Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev Fifth Summit-1976, Colombo ................................................................32 6. His Majesty Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev Sixth Summit-1979, Havana ..................................................................39 7. His Majesty Birendra Bir Bikram Shah Dev Seventh Summit-1983, New Delhi .........................................................46 -

Hotline Tel: + 49 .6221 653 0030 Fax: + 49 .6221 830 545 Email: [email protected] Http

FIAN International Secretariat P.O. Box 10 22 43 D-69012 Heidelberg Hotline Tel: + 49 .6221 653 0030 Fax: + 49 .6221 830 545 email: [email protected] http: www.fian.org 0507HNEP 19.04.2005 Nepal: Right to food of Kamaiya families threatened in Tikapur, eastern Kailali Around 848 Kamaiya (bonded labourers) families in Tikapur, eastern Kailali, have captured local airport land on the 17th of July 2004 in order to pressurize the government of Nepal to provide them with proper rehabilitation and land allocation. Kamaiyas belonged to the Kamaiya system of bonded labour from which they were liberated by the government in July 2000. During liberation the Kamaiyas were promised rehabilitation including land for their livelihood. But these promises were never kept and the Kamaiyas have been leading a life of destitution with threat of hunger and malnutrition. International action is needed to urge the government of Nepal to provide rehabilitation and land to the Kamaiyas. It is the state obligation to rehabilitate the freed Kamaiyas and fulfil their right to feed themselves. Please write polite letters to the Minister of Land reforms with a copy to the His Majesty King of Nepal requesting them to undertake effective and systematic rehabilitation of the Kamaiya families. Profile Nepal is surrounded by the great heights of the Himalayas and the People's Republic of China to the North and India to the South. Nepal is primarily an agricultural country. The Kamaiya families belong to the Kamaiya system of bonded labour, which was in practice in some regions of Nepal. When the Kamaiyas were unable to earn a livelihood or did not earn enough as they were either landless or did not have work they would take loans from landlords in order to survive or feed themselves. -

Rashtriya Prajatantra Party – Recruitment of Children

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: NPL31734 Country: Nepal Date: 14 May 2007 Keywords: Nepal – Chitwan – Maoist insurgency – Peace process – Rashtriya Prajatantra Party – Recruitment of children This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Was Bharatput Chitwan an area affected by the Maoist insurgency, particularly in 2003 and 2004? 2. Has the security situation improved since the peace agreement signed between the government and the Maoists in November 2006 and former Maoist rebels were included in the parliament? 3. Please provide some background information about the Rashtriya Prajatantra Party - its policies, platform, structure, activities, key figures - particularly in the Bharatpur/Chitwan district. 4. Please provide information on the recruitment of children. RESPONSE 1. Was Bharatput Chitwan an area affected by the Maoist insurgency, particularly in 2003 and 2004? The available sources indicate that the municipality of Bharatpur and the surrounding district of Chitwan have been affected by the Maoist insurgency. There have reports of violent incidents in Bharatpur itself, which is the main centre of Chitwan district, but it has reportedly not been as affected as some of the outlying villages of Chitwan. A map of Nepal is attached for the Member’s information which has Bharatpur marked (‘Bharatpur, Nepal’ 1999, Microsoft Encarta – Attachment 1). A 2005 Research Response examined the presence of Maoist insurgents in Chitwan, but does not mention Maoists in Bharatpur. -

Chronology of Major Political Events in Contemporary Nepal

Chronology of major political events in contemporary Nepal 1846–1951 1962 Nepal is ruled by hereditary prime ministers from the Rana clan Mahendra introduces the Partyless Panchayat System under with Shah kings as figureheads. Prime Minister Padma Shamsher a new constitution which places the monarch at the apex of power. promulgates the country’s first constitution, the Government of Nepal The CPN separates into pro-Moscow and pro-Beijing factions, Act, in 1948 but it is never implemented. beginning the pattern of splits and mergers that has continued to the present. 1951 1963 An armed movement led by the Nepali Congress (NC) party, founded in India, ends Rana rule and restores the primacy of the Shah The 1854 Muluki Ain (Law of the Land) is replaced by the new monarchy. King Tribhuvan announces the election to a constituent Muluki Ain. The old Muluki Ain had stratified the society into a rigid assembly and introduces the Interim Government of Nepal Act 1951. caste hierarchy and regulated all social interactions. The most notable feature was in punishment – the lower one’s position in the hierarchy 1951–59 the higher the punishment for the same crime. Governments form and fall as political parties tussle among 1972 themselves and with an increasingly assertive palace. Tribhuvan’s son, Mahendra, ascends to the throne in 1955 and begins Following Mahendra’s death, Birendra becomes king. consolidating power. 1974 1959 A faction of the CPN announces the formation The first parliamentary election is held under the new Constitution of CPN–Fourth Congress. of the Kingdom of Nepal, drafted by the palace. -

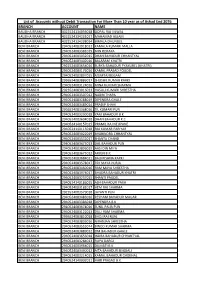

Branch Account Name

List of Accounts without Debit Transaction For More Than 10 year as of Ashad End 2076 BRANCH ACCOUNT NAME BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134056018 GOPAL RAJ SILWAL BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134231017 MAHAMAD ASLAM BAUDHA BRANCH 4322524134298014 BIMALA DHUNGEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083918012 KAMALA KUMARI MALLA BENI BRANCH 2940524083381019 MIN ROKAYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083932015 DHAN BAHADUR CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083402016 BALARAM KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2922524083654016 SURYA BAHADUR PYAKUREL (KHATRI) BENI BRANCH 2940524083176016 KAMAL PRASAD POUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524083897015 MUMTAJ BEGAM BENI BRANCH 2936524083886017 SHUSHIL KUMAR KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083124016 MINA KUMARI SHARMA BENI BRANCH 2923524083016013 HASULI KUMARI SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083507012 NABIN THAPA BENI BRANCH 2940524083288019 DIPENDRA GHALE BENI BRANCH 2940524083489014 PRADIP SHAHI BENI BRANCH 2936524083368016 TIL KUMARI PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083230018 YAM BAHADUR B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083604018 DHAN BAHADUR K.C BENI BRANCH 2940524140157015 PRAMIL RAJ NEUPANE BENI BRANCH 2940524140115018 RAJ KUMAR PARIYAR BENI BRANCH 2940524083022019 BHABINDRA CHHANTYAL BENI BRANCH 2940524083532017 SHANTA CHAND BENI BRANCH 2940524083475013 DAL BAHADUR PUN BENI BRANCH 2940524083896019 AASI DIN MIYA BENI BRANCH 2940524083675012 ARJUN B.K. BENI BRANCH 2940524083684011 BALKRISHNA KARKI BENI BRANCH 2940524083578017 TEK MAYA PURJA BENI BRANCH 2940524083460016 RAM MAYA SHRESTHA BENI BRANCH 2940524083974017 BHADRA BAHADUR KHATRI BENI BRANCH 2940524083237015 SHANTI PAUDEL BENI BRANCH 2940524140186015 -

The Abolition of Monarchy and Constitution Making in Nepal

THE KING VERSUS THE PEOPLE(BHANDARI) Article THE KING VERSUS THE PEOPLE: THE ABOLITION OF MONARCHY AND CONSTITUTION MAKING IN NEPAL Surendra BHANDARI Abstract The abolition of the institution of monarchy on May 28, 2008 marks a turning point in the political and constitutional history of Nepal. This saga of constitutional development exemplifies the systemic conflict between people’s’ aspirations for democracy and kings’ ambitions for unlimited power. With the abolition of the monarchy, the process of making a new constitution for the Republic of Nepal has started under the auspices of the Constituent Assembly of Nepal. This paper primarily examines the reasons or causes behind the abolition of monarchy in Nepal. It analyzes the three main reasons for the abolition of monarchy. First, it argues that frequent slights and attacks to constitutionalism by the Nepalese kings had brought the institution of the monarchy to its end. The continuous failures of the early democratic government and the Supreme Court of Nepal in bringing the monarchy within the constitutional framework emphatically weakened the fledgling democracy, but these failures eventually became fatal to the monarchical institution itself. Second, it analyzes the indirect but crucial role of India in the abolition of monarchy. Third, it explains the ten-year-long Maoist insurgency and how the people’s movement culminated with its final blow to the monarchy. Furthermore, this paper also analyzes why the peace and constitution writing process has yet to take concrete shape or make significant process, despite the abolition of the monarchy. Finally, it concludes by recapitulating the main arguments of the paper. -

Zeittafel Zur Nepalischen Geschichte Vor 60.000.000 Jahren Beginn Der Auffaltung Des Himalaya Vor 400-300.000 Jahren Entstehung Der Großen Himalayaseen (U

Zeittafel zur nepalischen Geschichte vor 60.000.000 Jahren Beginn der Auffaltung des Himalaya vor 400-300.000 Jahren Entstehung der großen Himalayaseen (u. a. im Kathmandutal) ca. 1500-1000 v.u.Z. Zuwanderung der ersten tibeto-mongolischen Völker (Kiranti) seit 1000 v.u.Z.. Zuwanderung der Khas-Bevölkerung ins westliche Nepal 7. Jh. v. -1. Jh. n.u.Z. legendenumwobene Kiranti-Zeit im Kathmandutal 544 v.u.Z. Geburt Buddhas in Lumbini, im nepalischen Tarai 250 v.u.Z. der buddhistische Kaiser Ashoka aus Indien besucht Lumbini 1. Jh. v.u.Z. erste Tamang-Gruppen siedeln im nördlichen Bagmati-Gebiet 1. Jh. erste Tamu (Gurung) siedeln im Gebiet des heutigen Mustang und Manang 464-505 vom Licchavi-Herrscher Manadeva I aus dem Kathmandutal sind erstmals Inschriften erhalten ca. 500 die Tamu (Gurung) siedeln südlich des Annapurna 7. Jh. Teile Nepals unter dem Einfluß des mächtigen großtibetischen Reiches; weitere Zuwanderung tibeto-mongolischer Völkerschaften 879 Ende der Licchavi-Herrschaft im Kathmandutal; Beginn der Newar-Zeitrechnung (Nepal Sambat ) 11.-12. Jh. erneute Zuwanderungswelle tibeto-mongolischer Völker 12.-14. Jh. Blütezeit des Khas-Reiches von Westnepal 1200 Beginn der Malla-Herrschaft im Kathmandutal ab 13. Jh. hohe Hindukasten aus Nordindien, insbesondere Rajasthan, fliehen nach Khasan, d. i. das westnepalische Hügelland ( pahar ) 1349 kurze Muslim-Invasion bis ins Kathmandutal 1382-1395 Jayasthiti Malla Herrscher im Kathmandutal; dortige Kodifizierung des Hindurechts 14.-15. Jh. die hohen Hindukasten dehnen ihre Macht in Westnepal aus; Beginn der Hinduisierung und Chetriierung der Magar- und Khas-Eliten 1428-1482 Yaksha Malla Herrscher im Kathmandutal; Blütezeit der Malla-Dynastie; danach Reichsteilung ca. -

1990 Nepal R01769

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 8 Tab Number: 24 Document Title: 1991 Nepalese Elections: A Pre- Election Survey November 1990 Document Date: 1990 Document Country: Nepal lFES ID: R01769 • International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1620 I STREET. NW "SUITE 611 "WASHINGTON. D.c. 20006 "1202) 828·8507 • • • • • Team Members Mr. Lewis R. Macfarlane Professor Rei Shiratori • Dr. Richard Smolka Report Drafted by Lewis R. Macfarlane This report was mcuJe possible by a grant • from the U.S. Agency for International Development Any person or organization is welcome to quote information from this report if it is attributed to IFES. • • BOARD OF Patricia Hutar James M. Cannon Randal C. Teague FAX: 1202) 452{)804 DIRECTORS Secretary Counsel Charles T. Manatt F. Clihon White Robert C. Walker • Chairman Treasurer Richard M. Scammon • • Table of Contents Mission Statement ............................ .............. i • Executive Summary .. .................. ii Glossary of Terms ............... .. iv Historical Backgrmlnd ........................................... 1 History to 1972 ............................................ 1 • Modifications in the Panchayat System ...................... 3 Forces for Change. ........ 4 Transformation: Feburary-April 1990.... .................. 5 The Ouest for a New Constitution. .. 7 The Conduct of Elections in Nepal' Framework and PrQce~lres .... 10 Constitution: Basic Provisions. .................. 10 • The Parliament. .. ................. 10 Electoral Constituency and Delimitation Issues ...........