Spectres of Modernism: Authorship, Reception and Intention in Witter Bynner and Arthur Davison Ficke's Spectra Hoax

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Howard Willard Cook, Our Poets of Today

MODERN AMERICAN WRITERS OUR POETS OF TODAY Our Poets of Today BY HOWARD WILLARD COOK NEW YORK MOFFAT, YARD & COMPANY 1919 COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY MOFFAT, YARP & COMPANY C77I I count myself in nothing else so happy as in a soul remembering my good friends: JULIA ELLSWORTH FORD WITTER BYNNER KAHLIL GIBRAN PERCY MACKAYE 4405 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To our American poets, to the publishers and editors of the various periodicals and books from whose pages the quotations in this work are taken, I wish to give my sincere thanks for their interest and co-operation in making this book possible. To the following publishers I am obliged for the privilege of using selections which appear, under their copyright, and from which I have quoted in full or in part: The Macmillan Company: The Chinese Nightingale, The Congo and Other Poems and General Booth Enters Heaven by Vachel Lindsay, Love Songs by Sara Teasdale, The Road to Cas- taly by Alice Brown, The New Poetry and Anthology by Harriet Monroe and Alice Corbin Henderson, Songs and Satires, Spoon River Anthology and Toward the Gulf by Edgar Lee Masters, The Man Against the Sky and Merlin by Edwin Arlington Rob- inson, Poems by Percy MacKaye and Tendencies in Modern American Poetry by Am> Lowell. Messrs. Henry Holt and Company: Chicago Poems by Carl Sandburg, These Times by Louis Untermeyer, A Boy's Will, North of Boston and Mountain Interval by Robert Frost, The Old Road to Paradise by Margaret Widdener, My Ireland by Francis Carlin, and Outcasts in Beulah Land by Roy Helton. Messrs. -

&.H Urt F!"Nettv'" 5T Y

f{OTT0 tsEDUPLICATTD 0B USID b/II'HOUTPERi"iIsSi0i\ Iii SiAii:il r.lF .rlii i;fA THE CI]RE LIBRARY OF FFIANCISH. FLAHERTY ttl shaLl speak to you of riobert Flahertyt:; method, because this method and the way it came to be i-s, I bel-ieve, the impa:-bant legacy he left use becauge for rne it was ttle greatest experience of my life with hj-m." -nd Frances Hubbard Flaherty Ln THE IIDYSSIYOFAFili'"l -MAKTR f!"nettv'" 5t y -&.h_urt Be'ua Phi Mu Chapbook Urbana, Ilfinois, 196A. tis n r Al_L artrr sei6 Robert F-'t_aherty, a kind of exp.loring. io discover and ' reveal is tl-re way every altist sef,s abcut his businc:ss,r Th': explorersr the iiscoverers, are the tran;i"crmers of the bror.'l-d. They are the scientist ciscovering new fec";, the pnit::sllther d:r-sc'ove-''ing:n nerv fac; new idea' Abc-rveal-i, they are the artist, the poet, tfre seer, Lrno oui of the crucible cf nelv fact and new idea bring new.l-ife, nera'power, new motiver anci a cleep refresi.ment. They disc;ver for us the new imsge.tl t'I-t was as an exp-lorer that Robert FJ-3herty came into fil-ms...tl It is as an explorer that Frances Fiahertv has searched to srticulate the j-n essence of histrmetho,l ,irthe rneanings his struggles, the fuLfiL.l-ment in his trway of seeing.tt Seeki.ng to share the richness of tisttitnportant legacyrI she has mineci worlds of words and ci:_stilled multiple nieanings into one worci: Inon-precOnaep I ttThe word I ha,ye chosen i.s ti.on, an eXp-lorelt s wo.rd. -

Frieda Lawrence

Frieda Lawrence: An Inventory of Her Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator Lawrence, Frieda, 1879-1956 Title Frieda Lawrence Collection Dates: 1870-1969 Extent 9 boxes (3.75 linear feet), 1 galley folder, 4 oversize folders Abstract: This collection includes diaries, essays, and drafts of Not I, But the Wind, and Frieda Lawrence, the Memoirs and Correspondence, as well as correspondence. Much of the correspondence is of a personal nature, but some has to do with copyrights and royalties from husband D.H. Lawrence's works. RLIN Record # TXRC98-A6 Languages English, and German. Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1957-1990 (R2792, R4244, R4806, R4933, R6625, R7016, R6625, R6627, G8503, G5045) Processed by Chelsea Jones, 1998 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Lawrence, Frieda, 1879-1956 Biographical Sketch Born Emma Maria Frieda Johanna Baroness (Freiin) von Richthofen, Frieda Lawrence (1879-1956) was the second of three daughters born to Prussian Baron Friedrich von Richthofen and Anna Marquier von Richthofen. The family lived in a rural suburb of Metz, an area recently conquered in the Franco-Prussian War and subjected to a regime of forced Germanization. Frieda attended a local Roman Catholic convent school but found few friends among the French population. Her social world was composed of her sisters, with whom she alternately competed for parental attention and allied herself with in order to manipulate their parents, the family servants in whose care the girls were generally left, and Prussian soldiers whom she met while playing in the trenches left over from the war. -

The Poets 77 the Artists 84 Foreword

Poetry . in Crystal Interpretations in crystal of thirty-one new poems by contemporary American poets POETRY IN CRYSTAL BY STEUBEN GLASS FIRST EDITION ©Steuben Glass, A Division of Corning Glass Works, 1963 Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 63-12592 Printed by The Spiral Press, New York, with plates by The Meriden Gravure Company. Contents FOREWORD by Cecil Hemley 7 THE NATURE OF THE C OLLECTIO N by John Monteith Gates 9 Harvest Morning CONRAD A IK EN 12 This Season SARA VAN ALSTYNE ALLEN 14 The Maker W. 1-1 . AU DEN 16 The Dragon Fly LO U I SE BOGAN 18 A Maze WITTER BYNNER 20 To Build a Fire MELV ILL E CANE 22 Strong as Death GUSTAV DAVID SON 24· Horn of Flowers T H 0 M A S H 0 R N S B Y F E R R I L 26 Threnos JEAN GARR I GUE 28 Off Capri HORACE GREGORY so Stories DO NA LD H ALL S2 Orpheus CEC IL HEMLEY S4 Voyage to the Island ROB ERT HILLYER 36 The Certainty JOH N HOLMES S8 Birds and Fishes R OB I NSON JEFFER S 40 The Breathing DENISE LEVERTOV 42 To a Giraffe MARIANNE MOORE 44 The Aim LOUISE TOWNSEND NICHOLL 46 Pacific Beach KENNETH REXROTH 48 The Victorians THEODORE ROETHKE 50 Aria DELMORE SCHWARTZ 52 Tornado Warning KARL SHAPIRO 54 Partial Eclipse W. D. SNODGRASS 56 Who Hath Seen the Wind? A. M. SULLIVAN 58 Trip HOLLIS SUMMERS 60 Models of the Universe MAY SWENSON 62 Standstill JOSEPH TUSIANI 64 April Burial MARK VAN DOREN 66 Telos JOHN HALL WHEELOCK 68 Leaving RICHARD WILBUR 70 Bird Song WILL I AM CARL 0 S WILL I AMS 72 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES The Poets 77 The Artists 84 Foreword CECIL HEMLEY President, 'The Poetry Society of America, 19 61-19 6 2 Rojects such as Poetry in Crystal have great significance; not only do they promote collaboration between the arts, but they help to restore the artist to the culture to which he belongs. -

LIBRARY of CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 Poetry Nation

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 poetry nation INSIDE Rosa Parks and the Struggle for Justice A Powerful Poem of Racial Violence PLUS Walt Whitman’s Words American Women Poets How to Read a Poem WWW.LOC.GOV In This Issue MARCH/APRIL 2015 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE FEATURES Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 4 No. 2: March/April 2015 Mission of the Library of Congress The Power of a Poem 8 Billie Holiday’s powerful ballad about racial violence, “Strange Fruit,” The mission of the Library is to support the was written by a poet whose works are preserved at the Library. Congress in fulfilling its constitutional duties and to further the progress of knowledge and creativity for the benefit of the American people. National Poets 10 For nearly 80 years the Library has called on prominent poets to help Library of Congress Magazine is issued promote poetry. bimonthly by the Office of Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and Beyond the Bus 16 The Rosa Parks Collection at the Library sheds new light on the research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in remarkable life of the renowned civil rights activist. 6 the United States. Research institutions and Walt Whitman educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. LCM is also available on the web at www.loc.gov/lcm. -

April 1917 543 Cass Street, Chicago

VOL. X NO. I APRIL 1917 My People Carl Sandburg 1 Loam—The Year—Chicago Poet—Street Window— Adelaide Crapsey—Repetitions—Throw Roses—Fire- logs — Baby Face — Moon — Alix — Gargoyle — Prairie Waters—Moon-set—Wireless—Tall Grass—Bringers The Reawakening—Two Epitaphs . Walter de la Mare 12 Prussians Don't Believe in Dreams—To a French Aviator Fallen in Battle . Morris Gilbert 14 Out of Mexico . Grace Hazard Conkling 18 Velardeña Sunset—Santa Maria del Rio—The Museum —Gulf View—Spring Day—Patio Scene The Fugitive—The Crowning Gift . Gladys Cromwell 21 Easter Evening .... James Church Alvord 23 A Woman—The Stranger—To an Old Couple Scudder Middleton 24 Praise—To— William Saphier 26 Toadstools Alfred Kreymborg 27 Love Was Dead—Lanes—Again—Courtship—Sir Hob bledehoy—1914—Dirge Editorial Comment 32 The City and the Tower—Verner von Heidenstam Reviews . 38 Our Contemporaries—Correspondence—Notes . SO Copyright 1917 by Harriet Monroe. All rights reserved 543 CASS STREET, CHICAGO $1.50 PER YEAR SINGLE NUMBERS, 15 CENTS Published monthly by Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1025 Fine Arts Building, Chicago. Entered as second-class matter at Postoffice, Chicago. , VOL. X No. I APRIL 1917 MY PEOPLE MY people are gray, pigeon gray, dawn gray, storm gray. I call them beautiful, and I wonder where they are going. LOAM In the loam we sleep, In the cool moist loam, To the lull of years that pass And the break of stars, From the loam, then, The soft warm loam, We rise: To shape of rose leaf, Of face and shoulder. [1] POETRY: A Magazine of Verse We stand, then, To a whiff of life, Lifted to the silver of the sun Over and out of the loam A day. -

Indianism and the Modernist Literary Field

ABORIGINAL ISSUES: INDIANISM AND THE MODERNIST LITERARY FIELD By Elizabeth S. Barnett Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in English August, 2013 Nashville, TN Approved: Professor Vera Kutzinski Professor Mark Wollaeger Professor Allison Schachter Professor Ellen Levy For Monte and Bea ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have been very fortunate in my teachers. Vera Kutzinski’s class was the first moment in graduate school that I felt I belonged. And she has, in the years since, only strengthened my commitment to this profession through her kindness and intellectual example. Thank you for five years of cakes, good talks, and poetry. One of my fondest hopes is that I have in some way internalized Mark Wollaeger’s editorial voice. He has shown me how to make my writing sharper and more relevant. Allison Schachter has inspired with her range and candor. My awe of Ellen Levy quickly segued into affection. I admire her way of looking, through which poetry and most everything seems more interesting than it did before. My deep thanks to Vanderbilt University and to the Department of English. I’ve received a wonderful education and the financial support to focus on it. Much of this is due to the hard work the Directors of Graduate Studies, Kathryn Schwarz and Dana Nelson, and the Department Chairs, Jay Clayton and Mark Schoenfield. I am also grateful to Professor Schoenfield for the opportunity to work with and learn from him on projects relating to Romantic print culture and to Professor Nelson for her guidance as my research interests veered into Native Studies. -

The Sculptor's Funeral

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications -- Department of English English, Department of 2016 Buried in Plain Sight: Unearthing Willa Cather’s Allusion to Thomas William Parsons’s “The Sculptor’s Funeral” Melissa J. Homestead University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Modern Literature Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Homestead, Melissa J., "Buried in Plain Sight: Unearthing Willa Cather’s Allusion to Thomas William Parsons’s “The cS ulptor’s Funeral”" (2016). Faculty Publications -- Department of English. 182. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishfacpubs/182 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications -- Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Studies in American Fiction 43:2 (2016), pp. 207–229. doi 10.1353/saf.2016.0010 Copyright © 2016 by Johns Hopkins University Press. Used by permission. digitalcommons.unl.edu Buried in Plain Sight: Unearthing Willa Cather’s Allusion to Thomas William Parsons’s “The Sculptor’s Funeral” Melissa J. Homestead University of Nebraska-Lincoln n January 1905, Willa Cather’s story “The Sculptor’s Funeral” appeared in McClure’s Magazine and shortly thereafter in her first book of fiction,The Troll Garden, a collec- Ition of stories about art and artists. In the story, the body of sculptor Harvey Mer- rick arrives in his hometown of Sand City, Kansas, on a train from Boston, accompa- nied by his friend and former student, Henry Steavens. -

Debs and the Poets

GIFT or eg CJU^A^ cfl II. DEBS AND THE POETS DEBS AND THE POETS ^ Edited by RUTH LE PRADE . With an Introduction by UPTON SINCLAIR PDBLI8HBD BY UPTON SINCLAIR PASADENA. CAL. Copyright, 1920 BY RUTH U PRAD 9653 (To E. V. D.) BY WITTER BYNNER Nine six five three, Numbers heard in heaven, Numbers whispered breathlessly, Mystical as seven. Numbers lifted among stars To acclaim and hail Another heart behind the bars. Another God in jail, Tragic in their symmetry, Crucified and risen, Nine six five three, From Atlanta Prison. ^48716 INTRODUCTION United States has an old man in prison THEin the Federal Penitentiary of Atlanta. The government regards this old man as a common felon, and treats him as such; shaves his head, puts a prison suit upon him, feeds him upon prison food, and locks him in a steel-barred cell fourteen consecutive hours out of each twenty-four. But it appears that there are a great many people in the United States and other countries who do not regard this old man as a common felon; on the contrary, they regard him as a hero, a martyr, even a saint. It appears that the list of these people includes some of the greatest writers and the greatest minds of Europe and America. These persons have been moved to indignation by the treatment of the old man and they have expressed their indig- nation. Ruth Le Prade has had the idea of col- lecting their utterances. Here are poems by twenty-four poets, and letters from a score or two of other writers. -

17 April 28 V2.Indd

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Volume 17, No. 17 A Weekly Newspaper for the Library Staff April 28, 2006 Police Recognized for CFC Support Report Assesses Future of Catalogs In a Digital World he Library recently issued a report that challenges assumptions about Tthe traditional library catalog and proposes new directions for the research library catalog in the digital era. Commissioned by the Library and prepared by Associate University Librar- ian Karen Calhoun of Cornell University, the report assesses the impact of the Internet on the traditional online public- access catalog and concludes that library patrons want easy-to-use catalogs that are accessible on the Web. The report, “The Changing Nature of Gail Fineberg the Catalog and Its Integration with Other Library Police, with a force of more than 109, received the top award for 100 percent par- Discovery Tools,” grew out of the Library ticipation in the 2005 Combined Federal Campaign (CFC). Presenting the CFC Presi- of Congress Bicentennial Conference on dent’s Award on behalf of the Librarian and the Library, Deputy Librarian Donald L. Scott said, “We do appreciate what you do. Not only do you keep us safe, but you care.” In Bibliographic Control for the New Mil- particular, he noted the leadership of Offi cer G. L. Murdock, who rallied police support for lennium, held in November 2000. The the CFC. Pictured here are, from left, Ken Lopez, director for the Offi ce of Security and conference also led to new curricula Emergency Preparedness; Sgt. A. E. Butler; Capt. Michael J. Murphy; Offi cer Murdock; for schools of library science, continu- Scott; and Robert Handloff, manager of the 2005 campaign. -

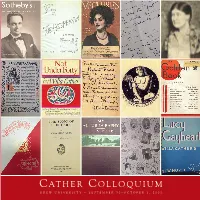

Cather Program

C ATHER C OLLOQUIUMC ATHER DREW UNIVERSITYC OLLOQUIUM • SEPTEMBER 30–OCTOBER 1, 2005 C ATHER C OLLOQUIUM DREW UNIVERSITY • SEPTEMBER 30–OCTOBER 1, 2005 Sponsored by T HE C ASPERSEN S CHOOL OF G RADUATE S TUDIES T HE U NIVERSITY L IBRARY F RIENDS OF THE U NIVERSITY L IBRARY The Colloquium is part of the year-long celebration of the 50th anniversary of The Caspersen School TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 P ROGRAM 6 C ONCERT P ROGRAM 9 T HE C ATHER C OLLECTIONS 16 S PECIAL E XHIBIT A CCESS TO THE C ATHER C OLLECTIONS 1 7 T RIBUTE TO THE C ASPERSENS 18 S PECIAL T HANKS WILLA CATHER P ROGRAM CATHER COLLOQUIUM DREW UNIVERSITY Friday, September 30 (S.W. Bowne) 12:15-1:15 p.m. Buffet Lunch (Great Hall) 8:15-9:00 a.m. Continental Breakfast (Great Hall) 1:15-2:30 p.m. Plenary Session (Great Hall) 9:00-9:15 a.m. Jessica Rabin: “‘Honey, Do We Really Need Five Welcome and Introductions Copies of This?’: April Twilights Revisited,” James Pain, Dean, Caspersen School of Graduate Studies Anne Arundel Community College. Andrew D. Scrimgeour, Director, University Library Steve Shively: “Cather and the Menuhins: Who Merrill Skaggs, Baldwin Professor of Humanities Mentored Whom?”, Northwest Missouri State Robert Weisbuch, President, Drew University University. 9:15-10:45 a.m. 2:45-4:00 p.m. Plenary Session (Great Hall) Breakout Sessions (Mead Hall) John Murphy: “‘Cécile,’ A Rejected Fragment of Shadows: Founders Room: Bob Thacker, Chair Where Would It Go and What Would It Add?”, Mary Chinery: “Witter Bynner in the Cather Professor Emeritus, Brigham Young University. -

William Rose Benét Collection, 1845-1959 MSS. COLL. NO. 053 1.5 Linear Feet

William Rose Benét Collection, 1845-1959 MSS. COLL. NO. 053 1.5 linear feet Biographical Note William Rose Benét was born on February 2, 1886 in Fort Hamilton, N.Y. and died May 4, 1950. He was educated at Albany Academy and Yale University, Benét was a poet, editor, critic, anthologist, translator, and children's author. He wrote, edited, or collaborated on 36 books and was best known for his column "The Phoenix Nest" in the Saturday Review of Literature (1924-1950). Scope & Content The collection consists of galley proofs for books of poetry by various authors (Frances Frost, Howard Griffin, Alfred Noyes, Edith Sitwell and Stephen Spender). Also included are a large number of book jackets from various authors books of poetry, inventory list of books that were in the Benét library, and correspondence between St. Lawrence University, Yale University Library, Gramercy Book Shop (NYC) and Marjorie Flack Benét Box 1 BOOK JACKETS--from the Benet collection (Bold = ODY has book – Call no. of book follows the title) Crusade: A Collection of Forty Poems Captain John Waller Testament of Love: A Sonnet Sequence Audrey Wurdemann [PS 3545 .U7 T4 1938] [2 copies] Poetry Awards 1940 Editor Robert Thomas Moore Ziba James Pipes Ghosts [PS 3545 .H16 G45 1937] Edith Wharton Epics Myths & Legends of India [BL 2003 .T5 1956] Paul Thomas Poems From the Desert Members of the Eighth Army The Peterborough Anthology [PS 614 .G65] [2 copies] Gorman, [Jean Wright] Fear No More: A Book of Poems for the Present Time by Living English Poets Stamboul Train, An Entertainment