Swami Vivekananda 1863–1902

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of the Ramakrishna Mission and Human

TOWARDS SERVING THE MANKIND: THE ROLE OF THE RAMAKRISHNA MISSION AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT IN INDIA Karabi Mitra Bijoy Krishna Girls’ College Howrah, West Bengal, India sanjay_karabi @yahoo.com / [email protected] Abstract In Indian tradition religious development of a person is complete when he experiences the world within himself. The realization of the existence of the omnipresent Brahman --- the Great Spirit is the goal of the spiritual venture. Gradually traditional Hinduism developed negative elements born out of age-old superstitious practices. During the nineteenth century changes occurred in the socio-cultural sphere of colonial India. Challenges from Christianity and Brahmoism led the orthodox Hindus becoming defensive of their practices. Towards the end of the century the nationalist forces identified with traditional Hinduism. Sri Ramakrishna, a Bengali temple-priest propagated a new interpretation of the Hindu scriptures. Without formal education he could interpret the essence of the scriptures with an unprecedented simplicity. With a deep insight into the rapidly changing social scenario he realized the necessity of a humanist religious practice. He preached the message to serve the people as the representative of God. In an age of religious debates he practiced all the religions and attained at the same Truth. Swami Vivekananda, his closest disciple carried the message to the Western world. In the Conference of World religions held at Chicago (1893) he won the heart of the audience by a simple speech which reflected his deep belief in the humanist message of the Upanishads. Later on he was successful to establish the Ramakrishna Mission at Belur, West Bengal. -

Sri Ramakrishna & His Disciples in Orissa

Preface Pilgrimage places like Varanasi, Prayag, Haridwar and Vrindavan have always got prominent place in any pilgrimage of the devotees and its importance is well known. Many mythological stories are associated to these places. Though Orissa had many temples, historical places and natural scenic beauty spot, but it did not get so much prominence. This may be due to the lack of connectivity. Buddhism and Jainism flourished there followed by Shaivaism and Vainavism. After reading the lives of Sri Chaitanya, Sri Ramakrishna, Holy Mother and direct disciples we come to know the importance and spiritual significance of these places. Holy Mother and many disciples of Sri Ramakrishna had great time in Orissa. Many are blessed here by the vision of Lord Jagannath or the Master. The lives of these great souls had shown us a way to visit these places with spiritual consciousness and devotion. Unless we read the life of Sri Chaitanya we will not understand the life of Sri Ramakrishna properly. Similarly unless we study the chapter in the lives of these great souls in Orissa we will not be able to understand and appreciate the significance of these places. If we go on pilgrimage to Orissa with same spirit and devotion as shown by these great souls, we are sure to be benefited spiritually. This collection will put the light on the Orissa chapter in the lives of these great souls and will inspire the devotees to read more about their lives in details. This will also help the devotees to go to pilgrimage in Orissa and strengthen their devotion. -

Thevedanta Kesari February 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari February 2020 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story Sri Ramakrishna : A Divine Incarnation page 11 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 February of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Mylapore Rangoli competition To preserve and promote cultural heritage, the Mylapore Festival conducts the Kolam contest every year on the streets adjoining Kapaleswarar Temple near Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai. Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Tamil Nadu. Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 2 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2020 ory St er ov C 11 Sri Ramakrishna: A Divine Incarnation Swami Tapasyananda 46 20 Women Saints of FEATURES Vivekananda Varkari Tradition Rock Memorial Atmarpanastuti Arpana Ghosh 8 9 Yugavani 10 Editorial Sri Ramakrishna and the A Curious Boy 18 Reminiscences Pilgrimage Mindset 27 Vivekananda Way Gitanjali Murari Swami Chidekananda 36 Special Report 51 Pariprasna Po 53 The Order on the March ck et T a le 41 25 s Sri Ramakrishna Vijayam – Poorva: Magic, Miracles Touching 100 Years and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath t or ep R l ia c e 34 31 p S Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

Proposed Date of Transfer to IEPF

Folio Number First Name Last Name Address PINCode Amount Proposed of Securities Due(in Date of Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) A000745 ARCHANA DOSI C/O M K DOSI,ASSTT. GENERAL MANAGER,KUTESHWAR LIMESTONE MINE PO,GAIRTALAI BARHI KATN 5.00 16-AUG-2021 A002266 ANNAMMA ABRAHAM KARIMPIL HOUSE PANGADA PO,PAMPADY KOTTAYAM DT,KERALA STATE, 25.00 16-AUG-2021 A002410 ARVINDKUMAR AGARWAL C/O VINOD PUSTAK MANDIR,BAG MUZAFFAR KHAN,AGRA-2, 5.00 16-AUG-2021 A002592 ANIL KUMAR C/O DIAMOND AND DIAMOND,TAILORS & DRAPPERS SHOP NO 5,LAL RATTAN MARKET NAKODAR ROAD,JALANDHAR PUNJAB-1 35.00 16-AUG-2021 A006562 ANIRUDDH PAREKH FRANKLIN GREENS APTS,26 L 1 JFK BLDV,SOMERSET,N.J 08873 USA 50.00 16-AUG-2021 A006781 ASHOK PODDAR C/O KHETSIDAS RAMJIDAS,178 M G ROAD,CALCUTTA - 7, 3.00 16-AUG-2021 A007370 ALABHAI DHOKIA C/O RAMABEN ALABHAI DEDHIA,MITRAKUT SOCIETY PRATIK"",NR GRUH VIHAR SOC NR PTC,GROUND JUNAGADH 10.00 16-AUG-2021 B000036 B NAGARAJAPPA # 763/B 2ND CROSS,M B SHANKARAPPA LAYOUT,,TIPTUR 15.00 16-AUG-2021 B001040 BRIJESH KHARE HNO-A-85,AVAS VIKAS COLONY,NANDAPURA JHANSI,U P 5.00 16-AUG-2021 C000020 C RAVEENDRAN DR. C S RAVEENDRAN,RAJAM NURSING HOME,36-38 PALAYAMKOTTAI ROAD,TUTICORIN 5.00 16-AUG-2021 C000403 CHARU TRIVEDI C/59 GUNATIT NAGAR,JUNAGADH,GUJARAT, 8.00 16-AUG-2021 D006542 DEVIBEN JEBHAI C/O D G RANDERIA,10 ANAND NAGAR SOCIETY,MORABHAGOL RANDER,SURAT 5 60.00 16-AUG-2021 D006716 DILIP SHAH A-21 ANITA SOCIETY,PALDI,AHMEDABAD, 8.00 16-AUG-2021 D007001 DILIP MISHRA QR NO M-27,CHHEND COLONY,ROURKELA,ORISSA 200.00 16-AUG-2021 D007108 DEVASI VADHER LIMDA CHOWK,CHORVAD,, 3.00 16-AUG-2021 F000129 FRANKLIN OLIVEIRA 2 SANDERSON DRIVE,GUELPH,ONTARIO NIH 6T8,CANADA 50.00 16-AUG-2021 G000075 GANESH KAYASTHA POST BAG 36 NAVJIVAN,POST OFFICE B/H GUJARAT,VIDYAPITH ASHRAM ROAD,AHMEDABAD 8.00 16-AUG-2021 G000699 GOVIND NEMA 9/2 MANORAMAGANJ (MULCHHAL,COMPLEX) 401 'DEVASHISH APT,IN FRONT OF DIG BUNGLOW,INDORE M.P. -

Journal of Research & Innovations in Education (JRIE)

ISSN: 2349-2244 Journal of Research & Innovations in Education (JRIE) Volume 2, Issue 2 & 3, December 2015 & June 2016 1 Educational Status of Muslim Women in Malabar Region of Kerala - Dr. V.K. Jibin & Dr. C. Naseema 2 Emotional Intelligence Inventory: Construction and Standardisation - Professor (Dr.) N.A. Nadeem & Associate Prof. Seema Naz 3 Study of Adjustment of Various Socio-Metric Categories of Adolescent Students - Nighat Basu, Shagufta Rehman & Gawher Ahmad 4 Changing Paradigms of Higher Education: An Innovative Approach - Dr. Nazir Ahmad Gilkar 5 Comparative Study of Cognitive Functioning of Aged Women 60+ of Jammu and Srinagar - Prof. Neeru Sharma & Farhat Masoodi 6 A Study on Practice Teaching Programme in Teacher Education Institutions of Osmania University - Dr. Kadem Srinivas & Prof. R. G. Kothari 7 The Role of Constructivism in Inter/Multi-Disciplinary Studies - Dr. Efthikar Ahamed B 8 Mathematical Aptitude and Mathematical Problem-solving Performance: Three-wave Panel Analysis - Dr. Tarun Kumar Tyagi School of Education Central University of Kashmir Srinagar (J&K), India-190015 Chief Patron Prof. Mehraj-ud-Din Vice-Chancellor Central University of Kashmir Founder, Publisher & Editor-in-chief Prof. N. A. Nadeem Dean & Head School of Education, Journal of Research & Central University of Kashmir Innovations in (CUK) Srinagar-190015 Education Editors Prof. Nighat Basu Professor & Coordinator, Tr. Edu. School of Education, Central University of Kashmir Dr. Mohd Sayid Bhat Assistant Professor School of Education, Central University of Kashmir Dr. Ismail Thamarasseri Assistant Professor, School of Education, Central University of Kashmir Printed and Published at: Dilpreet Publishing House. Srinagar, J&K, India JRIE (c) 2015 Vol.02, No.02 & 03; Editorial Policy: The views expressed by the December, 2015 & June 2016 authors are their own and the editorial team is ISSSN: 2349-2244 not responsible in any way. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

REACH “For One’S Own Liberation and for the Newsletter of Vedanta Centres of Australia Welfare of the World.”

Motto: Atmano mokshartham jagad hitaya cha, REACH “For one’s own liberation and for the Newsletter of Vedanta Centres of Australia welfare of the world.” 85 Bland Street Ashfield, New South Wales 2131 Australia Website: www.vedantasydney.org; e-mail: [email protected];Phone: (02) 9705 9050; Fax: (02) 9705 9051 Sayings and Teachings Simplicity pays “One should not reason too much; it is enough if one loves the Lotus Feet of the Mother. Too much reasoning throws the mind into confusion. You get clear water if you drink from the surface of a pool. Put your hand deeper and stir the water and it becomes muddy. Therefore pray to God for devotion.” --- Sri Ramakrishna. The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna; Ramakrishna Math, Chennai, India, page186. Epitome of Motherhood “My son, you know the Master Temple of the Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi at the Ramakrishna Math, Belur Math The headquarters of the Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission, looked upon everyone as the Divine Howrah (West Bengal), India. Mother. This time he has left me behind to develop the ideal of CALENDAR OF FORTHCOMING EVENTS Motherhood on earth.” Function Centre Date --- Sri Sarada Devi. Brisbane Tuesday, 1st January 2008 The Message of Holy Mother; Birth Anniversary of Advaita Ashrama, Kolkata, Page 1. Holy Mother Melbourne Tuesday, 1st January 2008 Demand divinity Perth Sunday 30th December 2007 “There must be no fear. No begging, Sydney Sunday 30th December 2007 but demanding—demanding the Highest. The true devotees of the Birth Anniversary of Brisbane Saturday, 2nd February 2008 Mother are as hard, as adamant and Swami Vivekananda Melbourne Saturday, 26th January 2008 as fearless as lions. -

Halasuru Math Book List

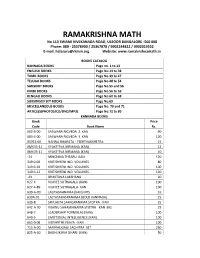

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

—No Bleed Here— Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness 23

Swami Vivekananda and Asian Consciousness Niraj Kumar wami Vivekananda should be credited of transformation into a great power. On the with inspiring intellectuals to work for other hand, Asia emerged as the land of Bud Sand promote Asian integration. He dir dha. Edwin Arnold, who was then the principal ectly and indirectly influenced most of the early of Deccan College, Pune, wrote a biographical proponents of panAsianism. Okakura, Tagore, work on Buddha in verse titled Light of Asia in Sri Aurobindo, and Benoy Sarkar owe much to 1879. Buddha stirred Western imagination. The Swamiji for their panAsian views. book attracted Western intellectuals towards Swamiji’s marvellous and enthralling speech Buddhism. German philosophers like Arthur at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche saw Bud on 11 September 1893 and his subsequent popu dhism as the world religion. larity in the West and India moulded him into a Swamiji also fulfilled the expectations of spokesman for Asiatic civilization. Transcendentalists across the West. He did not Huston Smith, the renowned author of The limit himself merely to Hinduism; he spoke World’s Religions, which sold over two million about Buddhism at length during his Chicago copies, views Swamiji as the representative of the addresses. He devoted a complete speech to East. He states: ‘Buddhism, the Fulfilment of Hinduism’ on 26 Spiritually speaking, Vivekananda’s words and September 1893 and stated: ‘I repeat, Shakya presence at the 1893 World Parliament of Re Muni came not to destroy, but he was the fulfil ligions brought Asia to the West decisively. -

Spiritual Conversations with Swami Shankarananda Swami Tejasananda English Translation by Swami Satyapriyananda (Continued from the Previous Issue)

2 THE ROAD TO WISDOM Swami Vivekananda on Significance of Symbols—III n the heart of all these ritualisms, there Istands one idea prominent above all the rest—the worship of a name. Those of you who have studied the older forms of Christianity, those of you who have studied the other religions of the world, perhaps have marked that there is this idea with them all, the worship of a name. A name is said to be very sacred. In the Bible we read that the holy name of God was considered sacred beyond compare, holy consciously or unconsciously, man found beyond everything. It was the holiest of all the glory of names. names, and it was thought that this very Again, we find that in many different Word was God. This is quite true. What is religions, holy personages have been this universe but name and form? Can you worshipped. They worship Krishna, they think without words? Word and thought worship Buddha, they worship Jesus, and so are inseparable. Try if anyone of you can forth. Then, there is the worship of saints; separate them. Whenever you think, you hundreds of them have been worshipped all are doing so through word forms. The one over the world, and why not? The vibration brings the other; thought brings the word, of light is everywhere. The owl sees it in the and the word brings the thought. Thus the dark. That shows it is there, though man whole universe is, as it were, the external cannot see it. To man, that vibration is only symbol of God, and behind that stands visible in the lamp, in the sun, in the moon, His grand name. -

Remembering Swami Vivekananda and His Clarion Call to the Nation

Remembering Swami Vivekananda and his Clarion Call to the Nation (Presented by ‘Swami Vivekananda 150th Birth Anniversary Celebration Committee’, IISc) ABSTRACT “I Have a Truth to Teach, I, the Child of God” : Mr. Bishwabandhu Chattaraj This talk highlights the truth Swami Vivekananda wanted to teach the entire human race. To trace the source of this truth, one has to go deep into the trainings he received from his Master Sri Ramakrishna on the real import of Advaita Vedanta with practical examples. Although Shankaracharya propounded his concept – “Brahman is the only truth, the world is unreal” long back, the theory of Advaita Vedanta was confined to only scholastic exercise among a few scholars. Vivekananda took a vow that he would make the teachings of Vedanta comprehensible to all the common house-holders. To translate his mission into practice he set out to travel length and breadth across the country on foot. He met people from all walks of life and realized their ignorance, misery and squalor. He was burning with a fierce desire to demolish this evil. Ultimately he reached Kanyakumari and swam across the sea to the last piece of land of our motherland, where he sat for continuous meditation and visualized the injunctions he received from his Master. He set forth his immediate tasks as organizing all his brother disciples to come under one roof top with the motto of service ‘for one's own salvation and for the welfare of the world’ and undertaking the enormous task of educating the Indian masses. For arranging the finance for this enormous task, he decided to proceed to America to join the Parliament of religion, which he had declined to do earlier when Maharajas of different estates had approached him. -

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda Swami Vivekananda (Bengali: [ʃami bibekanɔndo] ( listen); 12 January 1863 – 4 Swami Vivekananda July 1902), born Narendranath Datta (Bengali: [nɔrendronatʰ dɔto]), was an Indian Hindu monk, a chief disciple of the 19th-century Indian mystic Ramakrishna.[4][5] He was a key figure in the introduction of the Indian philosophies of Vedanta and Yoga to the Western world[6][7] and is credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing Hinduism to the status of a major world religion during the late 19th century.[8] He was a major force in the revival of Hinduism in India, and contributed to the concept of nationalism in colonial India.[9] Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission.[7] He is perhaps best known for his speech which began, "Sisters and brothers of America ...,"[10] in which he introduced Hinduism at the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago in 1893. Born into an aristocratic Bengali Kayastha family of Calcutta, Vivekananda was inclined towards spirituality. He was influenced by his guru, Ramakrishna, from whom he learnt that all living beings were an embodiment of the divine self; therefore, service to God could be rendered by service to mankind. After Vivekananda in Chicago, September Ramakrishna's death, Vivekananda toured the Indian subcontinent extensively and 1893. On the left, Vivekananda wrote: acquired first-hand knowledge of the conditions prevailing in British India. He "one infinite pure and holy – beyond later travelled to the United States, representing India at the 1893 Parliament of the thought beyond qualities I bow down World's Religions. Vivekananda conducted hundreds of public and private lectures to thee".[1] and classes, disseminating tenets of Hindu philosophy in the United States, Personal England and Europe.