Realizing the Witch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benjamin Christensen Ckery" (Lon Chaney), „Hawk’S Nest" (Milton Silis), „The Haunted House" {C Hest Er Conk- 28

„The Devil’s Circus" (Norma Shearer), „Mo- Benjamin Christensen ckery" (Lon Chaney), „Hawk’s Nest" (Milton Silis), „The Haunted House" {C hest er Conk- 28. 9. 1879 - 1. 4. 1959 lin), „House of Horror" (Thelma Todd) og „Seven Footprints to Satan" (også Thelma Todd) — Benjamin Christensen selv satte dem ikke højt, men der skal nok være sære og in Benjamin Christensen, der døde den 1. april teressante effekter i flere af dem, og forhåbent 79 år gammel, var ikke glemt. Det Danske lig er de ikke sporløst forsvundet. Filmmuseum har for ikke så længe siden vist Efter „Seven Footprints to Satan" fulgte en hans debutfilm „Det hemmelighedsfulde X“ tiårig pause, så kom instruktøren igen i Dan (1913) og den af Dreyer iscenesatte „Michael“ mark, hvor han iscenesatte „Skilsmissens (1924), i hvilken Benjamin Christensen spiller Børn", „Barnet", „Gaa med mig hjem" og hovedrollen, og i „Kosmorama 7“ bragtes et „Damen med de lyse Handsker", bedst var de index over hans film. to første, værst den sidste, der satte et noget Den indgående analyse af Benjamin Chri pinligt punktum for Benjamin Christensens stensens værker, som endnu ikke er skrevet, hå instruktørkarriére. ber vi senere at kunne bringe i „Kosmorama“. Benjamin Christensens evner burde have Den afdøde instruktør fortjener den, han var ført ham ind i en endnu mere imposant kar en pioner, og han skabte en stor film, den be riere, men filmproducenterne er mildest talt rømte „Heksen“. ikke altid ideelle mæcener. Imidlertid var - Hans væsentligste pionerindsats i hine år, da og er - Christensen en af de få internationalt ingen med sikkerhed kunne sige, om filmen berømte danske filminstruktører, og i hvert ville udvikle sig til en kunstart, var den op fald „Heksen" er af varig værdi. -

Discovering the Dürer Cipher Hidden Secrets in Plain Sight Discovering the Dürer Cipher Hidden Secrets in Plain Sight

DISCOVERING THE DÜRER CIPHER HIDDEN SECRETS IN PLAIN SIGHT DISCOVERING THE DÜRER CIPHER HIDDEN SECRETS IN PLAIN SIGHT OCTOBER 8 –NOVEMBER 23 2012 Director Notes Discovering the Dürer Cipher explores the prints were made and seeks to strip away passions that ignite artists, collectors, and palimpsest titles in order to help us see scholars to pursue the hidden secrets of one clearly the images before us. of the great heroes of the Northern Renais- It is with great pleasure that the Rebecca sance, Albrecht Dürer. This exhibition Randall Bryan Art Gallery invites you to comprises more than forty prints gathered enjoy this catalog and exhibition of the together by collector Elizabeth Maxwell- brilliance of Albrecht Dürer. Our sincerest Garner. Inspired by her love of the artist, appreciation and thanks extend to Elizabeth she amassed this outstanding collection to Maxwell-Garner, whose passion and insights aid her research into why the artist produced have brought this collection together. his astonishingly unusual iconography and for whom these prints were made. Jim Arendt Her research has led her to a series of Director, Rebecca Randall Bryan Art Gallery startling conclusions not found in previous scholarly interpretations of Dürer prints. Of special note are her investigations into the interrelatedness of Dürer’s prints and his possible use of steganography, a form of concealed writing executed in such a manner that only the author and intended recipients are aware of its existence. Garner’s assertions draw attention to the inconsistency found in centuries of symbolic interpretation and reinterpretation of this popular artists work. Through detailed analysis of the city life of 15th and 16th century Nuremburg, Garner explores the social and economic climate in which these Foreward by Stephanie R. -

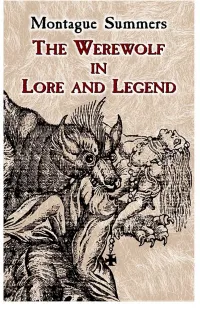

The Werewolf in Lore and Legend Plate I

Montague Summers The Werewolf IN Lore and Legend Plate I THE WARLOCKERS’ METAMORPHOSIS By Goya THE WEREWOLF In Lore and Legend Montague Summers Intrabunt lupi rapaces in uos, non parcentes gregi. Actus Apostolorum, XX, 29. DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. Mineola New York Bibliographical Note The Werewolf in Lore and Legend, first published in 2003, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1933 by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd., London, under the title The Werewolf. Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Summers, Montague, 1880-1948. [Werewolf] The werewolf in lore and legend / Montague Summers, p. cm. Originally published: The werewolf. London : K. Paul, Trench, Trubner, 1933. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-486-43090-1 (pbk.) 1. Werewolves. I. Title. GR830.W4S8 2003 398'.45—dc22 2003063519 Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc., 3 1 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501 CONTENTS I. The Werewolf: Lycanthropy II. The Werewolf: His Science and Practice III. The Werewolf in Greece and Italy, Spain and Portugal IV. The Werewolf in England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland V. The Werewolf in France VI. The Werewolf in the North, in Russia and Germany A Note on the Werewolf in Literature Bibliography Witch Ointments. By Dr. H. J. Norman Index LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS I. The Warlocks’ Metamorphosis. By Goya. Formerly in the Collection of the Duke d’Osuna II. A Werewolf Attacks a Man. From Die Emeis of Johann Geiler von Kaisersberg III. The Transvection of Witches. From Ulrich Molitor’s De Lamiis IV. The Wild Beast of the Gevaudan. -

Cinema Scandinavia Issue 2 May 2014 Compressed

CINEMA SCANDINAVIA issue 2 may 2014 Haxan Vampyr The Seventh Seal Carl Dreyer ....and more CINEMA SCANDINAVIA PB CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 1 COVER ART http://jastyoot.deviantart.com/ IN THIS ISSUE Editorial News Haxan and Vampyr Death in the Seventh Seal The Dream of Allan Grey Carl Dreyer Blad af Satans Bog Across the Pond Ordet Released this Month Festivals in May More Information Call for Papers CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 THE PARSONS WIDOW CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 3 Terje Vigen The Outlaw and his Wife WELCOME Welcome to the second issue of Cinema Scandinavia. This issue looks at the early Scandinavian cinema. Let me provide a brief overview of early Nordic film. Film came to the region in the late 1890s, and movies began to appear in the early 1900s. Danish cinema pioneer Peter Elfelt was the first Dane to make a film, and in the years 1896 through to 1912 he made over 200 films documenting Danish life. His first film was titled Kørsel med Grønlandske Hunde (Travelling with Greenlandic Dogs). During the silent era, Denmark and Sweden were the two biggest Nordic countries on the cinema stage. In Sweden, the greatest directors of the silent era were Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. Sjöström’s films often made poetic use of the Nordic landscape and played great part in developing powerful studies of character and emotion. Great artistic merit was also found in early Danish cinema. The period around the 1910’s was known as the ‘Golden Age’ of cinema in Denmark, and understandably so. With the increasing length of films there was a growing artistic awareness, which can be seen in Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910). -

Download As Pdf

Journal of Historical Fic�ons 3:1 2020 Editorial: ‘Historical Fic�ons’ When the World Changes Julie�e Harrisson John Fowles’s ‘Manchester baby’: forms of radicalism in A Maggot Julie Depriester Troubling Portrayals: Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1922), Documentary Form, and the Ques�on of Histor(iography) Erica Tortolani Editors: Natasha Alden – Alison Baker – Jacobus Bracker – Benjamin Dodds – Dorothea Flothow – Catherine Padmore – Yasemin Sahin – Julie�e Harrisson The Journal of Historical Fic�ons 3:1 2020 Editor: Dr Julie�e Harrisson, Newman University, UK Faculty of Arts, Society and Professional Studies Newman University Genners Lane Bartley Green, Birmingham B32 3NT United Kingdom Co-Editors: Dr Natasha Alden, Aberystwyth University; Alison Baker, University of East London; Jacobus Bracker, University of Hamburg; Dr Benjamin Dodds, Florida State University; Dr Dorothea Flothow, University of Salzburg; Dr Catherine Padmore, La Trobe University; Dr Yasemin Sahin, Karaman University. Advisory Board: Dr Jerome de Groot, University of Manchester Nicola Griffith Dr Gregory Hampton, Howard University Professor Farah Mendlesohn Professor Fiona Price, University of Chichester Professor Mar�na Seifert, University of Hamburg Professor Diana Wallace, University of South Wales ISSN 2514-2089 The journal is online available in Open Access at historicalfic�onsjournal.org © Crea�ve Commons License: A�ribu�on-NonCommercial-NoDeriva�ves 4.0 Interna�onal (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Birmingham 2020 Contents Editorial: ‘Historical Fictions’ When the World Changes -

An Examination of the Zugarramurdi Witch-Hunts and Three Debating Inquisitors, 1609 - 1614

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2011 Discovering El Cuaderno: An Examination of the Zugarramurdi Witch-Hunts and Three Debating Inquisitors, 1609 - 1614 Meredith Lindsay Howard College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Howard, Meredith Lindsay, "Discovering El Cuaderno: An Examination of the Zugarramurdi Witch-Hunts and Three Debating Inquisitors, 1609 - 1614" (2011). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 417. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/417 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Discovering El Cuaderno: An Examination of the Zugarramurdi Witch-Hunts and Three Debating Inquisitors, 1609-1614 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Lyon G. Tyler Department of History from The College of William & Mary By Meredith Lindsay Howard Accepted for_________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________ Professor LuAnn Homza, Director _________________________________ Professor Nicholas Popper _________________________________ Professor Erin Minear Williamsburg, VA April 25, 0211 Table of Contents -

Benjamin Christensen's Häxan

Troubling Portrayals: Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1922), Documentary Form, and the Question of Histor(iography) Erica Tortolani, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Abstract: This essay discusses the 1922 Benjamin Christensen film, Häxan (or, Witchcraft through the Ages), and ways in which it complicates genre, narrative, and historical representation. Combining historical facts backed by real artefacts from the era with narrative reenactments inserted throughout, Häxan blurs the lines between reality and fiction, history and storytelling, which, at first glance, de-legitimizes its positioning as a documentary film, and thereby undermines its historical representations. To the contrary, Häxan should instead be placed in a different category of nonfiction, one that is not bound by the limitations of documentary filmmaking as we have come to know it, in that it provides a rich, multifaceted account of the medieval era that must not be ignored. Offering a view of history that accounts for social, cultural, religious, and medical perspectives, the film is in fact a representation of the past that challenges dominant notions of witchcraft in the Middle Ages and beyond, and can thus be regarded as an important contribution to the historiography of the period. Moreover, the film makes important (and rather troubling) claims regarding the oppression of women during this era, which is introduced towards the end of my analysis. Keywords: Silent film, Benjamin Christensen, witchcraft, documentary, history, psychoanalysis In a 2016 interview with the movie review website SlashFilm, director Robert Eggers discussed some major influences for his horror film of that year, The Witch, citing cinematic classics including Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1972) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). -

'Der Er Jo Altid En Middel- Maadighed Ved Haanden, Når Geniets Stol

FILMEN I 100 ÅR ‘Der er jo altid en Middel- maadighed ved Haanden, når Geniets Stol bliver tom’ ...skriver Benjamin Christensen i sin novellesamling af Maren Pust 1Hollywood Skæbner’. Den danske instruktør prøvede ikke at være bitter over den medfart, han fik i filmbyen, var bidt af en gal ‘Spectator’ (såle men det var svært, især fordi han faktisk havde fortjent des underskrev han sig) og derfor bi bedre. Det Danske Filmmuseum viser i det første pro drog i pressen med polemiske ind gram i det nye dr en sene med 11 af hans film. læg om filmkunstens beskaffenhed. Han roterer sikkert i sin urne, nu da jeg sidder og citerer ham for den rfvinv er er sagt mere end nok om giver sig udslag i film af Eleanor h o ld n in g til amerikansk film, han 1 ^ / Nordisk og Laus film, men Glyn typen. Maa vi bede om virke skiftede nemlig mening sidenhen. jeg synes, at der er grund til at nævne lige talenter, instruerede af dygtige Men det er egentlig lidt interessant, Benjamin Christensens store indsats og litterært bevandrede instruktører, at han fremhævede Benjamin Chri (...) Film er gøgl og ikke kunst saa- i film, hvis indhold og handling er stensen som den person, der mulig længe, man ikke kommer bort fra taget ud af livet, og som følgelig er gjorde, at filmen kunne udvikle sig den amerikanske spekulation i den troværdige.” - Sådan skrev min beds til en kunstart fremfor blot at være daarlige smag, hvilken spekulation tefar i 1926, da han som stud.mag. ‘amerikansk spekulation i daarlig 38 smag’, for året før var Christensen han i øvrigt havde den blandede for Opera og champagne draget over til Guds eget land for nøjelse at stifte bekendtskab med Benjamin Christensen ville oprinde der at fortsætte sin karriere. -

Kosmorama 7 Det Danske Filmmuseums Tidsskrift 4

KOSMORAMA 7 DET DANSKE FILMMUSEUMS TIDSSKRIFT 4. APRIL 1955 Fra det spanske afsnit af ,,Blade af Satans bog” : Hallander Hellemann som Don Gomez. DANSK FILM I 50 ÅR Dette specialnummer af „Kosmorama" er helliget den danske films historie. 10 film skribenter — Marguerite Engberg, Erik S. Saxtorpk, Jørgen Stegelmann, Ib Monty, Werner Pedersen, Theodor Christensen, I. C. Lauritzen, Bjørn Rasmussen, Bent Petersen og Erik Ul~ richsen — behandler hver en 5-årig periode i tiden 1905—55. Inddelingen er foretaget af praktiske grunde og „dækker" ikke helt filmhistorisk, og naturligvis er der ikke op nået absolut „egalitet", da så mange forskellige ytrer sig, men vi håber dog, at denne danske filmhistorie en miniature kan være af værdi som oversigt. selskaber at dukke op. Søren Nielsens Blafrende dekorationer sensationsfilm (Biorama-film) nåede dog aldrig op på højde med Ole Olsens, det 1905-10 af Marguerite Engberg gjorde derimod de film, som det århusi anske udlejningsselskab Fotorama i 1909 begyndte at optage. Fotorama speciali I 1905 åbnede Ole Olsen sin biograf serede sig fra begyndelsen i historiske i Vimmelskaftet 47, efter at Constantin film. Den første film var „Den lille Philips en året i forvejen havde åbnet Hornblæser44, og senere fulgte f. eks. en „Kosmorama44, Danmarks første biograf. Holger Danske-film. Da konkurrencen I 1906 grundlagde Olsen Nordisk Films omkring 1911 blev Ole Olsen for nær Kompagni, Danmarks første filmselskab. gående, købte han blot de bedste in Peter Elfelt, hoffotografen, havde ganske struktører og skuespillere over til sig. vist allerede fra 1896 optaget reportage film af både kongehusets og borgerska På Nordisk arbejdede man videre med bets dagligliv og indspillet den første de samme genrer. -

Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings

Cheney_Hardcover_color:NealArthur.qxd 11/11/2013 12:45 PM Page 1 Cheney PETER LANG This book focuses on Sir Edward Burne-Jones’ mythical paint- ings from 1868 to 1886. His artistic training and traveling experiences, his love for the Greek-sculptress, Maria Zambaco, and his aesthetic sensibility provided the background for these mythical paintings. This book analyzes two main con- Edward Burne-Jones’ Edward Burne-Jones' Mythical Paintings Burne-Jones' Mythical Edward cepts: Burne-Jones’ assimilation of Neoplatonic ideal beauty as depicted in his solo and narrative paintings, and Burne-Jones’ fusion of the classical and emblematic traditions in his imagery. Mythical Paintings THE PYGMALION OF THE PRE-RAPHAELITE PAINTERS Liana De Girolami Cheney is presently Investigadora de Historia de Arte, SIELAE, Universidad de Coruña, Spain, retired Professor of Art History, Chairperson of the Depart- ment of Cultural Studies at UMASS Lowell. Dr. Cheney received her B.S./B.A. in psychology and philosophy from the University of Miami, Florida, her M.A. in history of art and aesthetics from the University of Miami, Florida, and her Ph.D. in Italian Renaissance and Baroque from Boston University, Massachusetts. Dr. Cheney is a Pre- Raphaelite, Renaissance and Mannerism scholar, author, and coauthor of numer- ous articles and books, including: Botticelli’s Neo-Platonism Images; Neoplatonism and the Arts; Neoplatonic Aesthetics: Music, Literature, and the Visual Arts; The Paint- ings of the Casa Vasari; Readings in Italian Mannerism; The Homes of Giorgio Vasari (English and Italian); Self-Portraits by Women Painters; Essays on Women Artists: “The Most Excellent”; Symbolism in the Arts; Pre-Raphaelitism and Medievalism in the Arts; Giorgio Vasari’s Teachers: Sacred and Profane Art; Giuseppe Arcimboldo: The Magic Paintings (English, French and German); Giorgio Vasari: pennello, pluma e ardore; Giorgio Vasari’s Prefaces: Art and Theory; Giorgio Vasari’s Artistic and Emblematic Manifestations; and Giorgio Vasari in Context. -

Viewer to Understand Witches and Eve As Natural Women

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Nature of the Natural Woman Ann Marie Adrian Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE & DANCE THE NATURE OF THE NATURAL WOMAN By ANN MARIE ADRIAN A Thesis submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Ann Marie Adrian defended this thesis on Monday, March 26th, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Stephanie Leitch Professor Directing Thesis Jack Freiberg Committee Member Lauren Weingarden Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to extend my utmost gratitude to my thesis advisor Dr. Stephanie Leitch. Her vast knowledge of art history and brilliant insight provided me with a strong foundation on which to begin this project. Her guidance, encouragement, and enthusiasm were invaluable in helping me through the research, writing and revising, and made this project most enjoyable. I would also like to thank my committee members Dr. Jack Freiberg and Dr. Lauren Weingarden, for helping me get off on the right foot and their advice in the final stages. Additionally, I extend my gratitude to the staff members of the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Pierpont Morgan Library and Museum, and the New York Public Library for their patience and cooperation with retrieving numerous prints, drawings and books for my research and graciously answering all of my questions. -

Witchcraft Through the Ages

Witchcraft through the Ages Thursday, October 31, 2013 ~ Grand Illusion Cinema, Seattle ~ Presented by The Sprocket Society Originally released by Svensk Filmindustri as Häxan (Sweden) and Heksen (Denmark), both translate as The Witch. Premiered on September 18, 1922 in Stockholm, Sweden; and November 7, 1922 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Retitled in 1926 as La sorcellerie à travers les âges (“Witchcraft through the Ages”) for its French premiere. Re-released in 1941 with a musical soundtrack by Emil Rosen, and a sound introduction by Benjamin Christensen. Written and Directed by Benjamin Christensen 1968 English sound version: Director of Photography: Johan Ankerstjerne Produced by Antony Balch Art Director: Richard Louw Narrated by William S. Burroughs Edited by Edla Hansen Musical score composed by Daniel Humair Original score by Jacob Gade Recorded at Studios Europasoner (Paris) Produced by Charles Magnusson 1968 score performed by Jean-Luc Ponty (violin), Michel Portal (flute), Bernard Lubat (piano organ), Guy Pedersen (double bass), and Daniel Humair (percussion). Danish-born Benjamin Christensen (1879-1959) had largely responsible for the groundbreaking quality of originally planned this to be the first in a trilogy about Swedish film, nurturing the likes of Victor Sjöström. superstition throughout history, but the intense Christensen persuaded him to buy and equip an entire controversy Häxan caused upon its release meant that studio for the production. After extensive preparation Helgeninde (The Woman Saint) and Ånder (Spirits) and casting, filming began at last – in utmost secrecy – would never be made. A review of the Danish premiere in late winter 1921, continuing well into the following called it “unvarnished perversity” and demanded October.