Benjamin Christensen's Häxan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benjamin Christensen Ckery" (Lon Chaney), „Hawk’S Nest" (Milton Silis), „The Haunted House" {C Hest Er Conk- 28

„The Devil’s Circus" (Norma Shearer), „Mo- Benjamin Christensen ckery" (Lon Chaney), „Hawk’s Nest" (Milton Silis), „The Haunted House" {C hest er Conk- 28. 9. 1879 - 1. 4. 1959 lin), „House of Horror" (Thelma Todd) og „Seven Footprints to Satan" (også Thelma Todd) — Benjamin Christensen selv satte dem ikke højt, men der skal nok være sære og in Benjamin Christensen, der døde den 1. april teressante effekter i flere af dem, og forhåbent 79 år gammel, var ikke glemt. Det Danske lig er de ikke sporløst forsvundet. Filmmuseum har for ikke så længe siden vist Efter „Seven Footprints to Satan" fulgte en hans debutfilm „Det hemmelighedsfulde X“ tiårig pause, så kom instruktøren igen i Dan (1913) og den af Dreyer iscenesatte „Michael“ mark, hvor han iscenesatte „Skilsmissens (1924), i hvilken Benjamin Christensen spiller Børn", „Barnet", „Gaa med mig hjem" og hovedrollen, og i „Kosmorama 7“ bragtes et „Damen med de lyse Handsker", bedst var de index over hans film. to første, værst den sidste, der satte et noget Den indgående analyse af Benjamin Chri pinligt punktum for Benjamin Christensens stensens værker, som endnu ikke er skrevet, hå instruktørkarriére. ber vi senere at kunne bringe i „Kosmorama“. Benjamin Christensens evner burde have Den afdøde instruktør fortjener den, han var ført ham ind i en endnu mere imposant kar en pioner, og han skabte en stor film, den be riere, men filmproducenterne er mildest talt rømte „Heksen“. ikke altid ideelle mæcener. Imidlertid var - Hans væsentligste pionerindsats i hine år, da og er - Christensen en af de få internationalt ingen med sikkerhed kunne sige, om filmen berømte danske filminstruktører, og i hvert ville udvikle sig til en kunstart, var den op fald „Heksen" er af varig værdi. -

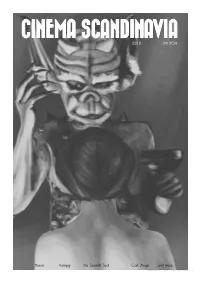

Cinema Scandinavia Issue 2 May 2014 Compressed

CINEMA SCANDINAVIA issue 2 may 2014 Haxan Vampyr The Seventh Seal Carl Dreyer ....and more CINEMA SCANDINAVIA PB CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 1 COVER ART http://jastyoot.deviantart.com/ IN THIS ISSUE Editorial News Haxan and Vampyr Death in the Seventh Seal The Dream of Allan Grey Carl Dreyer Blad af Satans Bog Across the Pond Ordet Released this Month Festivals in May More Information Call for Papers CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 THE PARSONS WIDOW CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 3 Terje Vigen The Outlaw and his Wife WELCOME Welcome to the second issue of Cinema Scandinavia. This issue looks at the early Scandinavian cinema. Let me provide a brief overview of early Nordic film. Film came to the region in the late 1890s, and movies began to appear in the early 1900s. Danish cinema pioneer Peter Elfelt was the first Dane to make a film, and in the years 1896 through to 1912 he made over 200 films documenting Danish life. His first film was titled Kørsel med Grønlandske Hunde (Travelling with Greenlandic Dogs). During the silent era, Denmark and Sweden were the two biggest Nordic countries on the cinema stage. In Sweden, the greatest directors of the silent era were Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. Sjöström’s films often made poetic use of the Nordic landscape and played great part in developing powerful studies of character and emotion. Great artistic merit was also found in early Danish cinema. The period around the 1910’s was known as the ‘Golden Age’ of cinema in Denmark, and understandably so. With the increasing length of films there was a growing artistic awareness, which can be seen in Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910). -

Download As Pdf

Journal of Historical Fic�ons 3:1 2020 Editorial: ‘Historical Fic�ons’ When the World Changes Julie�e Harrisson John Fowles’s ‘Manchester baby’: forms of radicalism in A Maggot Julie Depriester Troubling Portrayals: Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1922), Documentary Form, and the Ques�on of Histor(iography) Erica Tortolani Editors: Natasha Alden – Alison Baker – Jacobus Bracker – Benjamin Dodds – Dorothea Flothow – Catherine Padmore – Yasemin Sahin – Julie�e Harrisson The Journal of Historical Fic�ons 3:1 2020 Editor: Dr Julie�e Harrisson, Newman University, UK Faculty of Arts, Society and Professional Studies Newman University Genners Lane Bartley Green, Birmingham B32 3NT United Kingdom Co-Editors: Dr Natasha Alden, Aberystwyth University; Alison Baker, University of East London; Jacobus Bracker, University of Hamburg; Dr Benjamin Dodds, Florida State University; Dr Dorothea Flothow, University of Salzburg; Dr Catherine Padmore, La Trobe University; Dr Yasemin Sahin, Karaman University. Advisory Board: Dr Jerome de Groot, University of Manchester Nicola Griffith Dr Gregory Hampton, Howard University Professor Farah Mendlesohn Professor Fiona Price, University of Chichester Professor Mar�na Seifert, University of Hamburg Professor Diana Wallace, University of South Wales ISSN 2514-2089 The journal is online available in Open Access at historicalfic�onsjournal.org © Crea�ve Commons License: A�ribu�on-NonCommercial-NoDeriva�ves 4.0 Interna�onal (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Birmingham 2020 Contents Editorial: ‘Historical Fictions’ When the World Changes -

'Der Er Jo Altid En Middel- Maadighed Ved Haanden, Når Geniets Stol

FILMEN I 100 ÅR ‘Der er jo altid en Middel- maadighed ved Haanden, når Geniets Stol bliver tom’ ...skriver Benjamin Christensen i sin novellesamling af Maren Pust 1Hollywood Skæbner’. Den danske instruktør prøvede ikke at være bitter over den medfart, han fik i filmbyen, var bidt af en gal ‘Spectator’ (såle men det var svært, især fordi han faktisk havde fortjent des underskrev han sig) og derfor bi bedre. Det Danske Filmmuseum viser i det første pro drog i pressen med polemiske ind gram i det nye dr en sene med 11 af hans film. læg om filmkunstens beskaffenhed. Han roterer sikkert i sin urne, nu da jeg sidder og citerer ham for den rfvinv er er sagt mere end nok om giver sig udslag i film af Eleanor h o ld n in g til amerikansk film, han 1 ^ / Nordisk og Laus film, men Glyn typen. Maa vi bede om virke skiftede nemlig mening sidenhen. jeg synes, at der er grund til at nævne lige talenter, instruerede af dygtige Men det er egentlig lidt interessant, Benjamin Christensens store indsats og litterært bevandrede instruktører, at han fremhævede Benjamin Chri (...) Film er gøgl og ikke kunst saa- i film, hvis indhold og handling er stensen som den person, der mulig længe, man ikke kommer bort fra taget ud af livet, og som følgelig er gjorde, at filmen kunne udvikle sig den amerikanske spekulation i den troværdige.” - Sådan skrev min beds til en kunstart fremfor blot at være daarlige smag, hvilken spekulation tefar i 1926, da han som stud.mag. ‘amerikansk spekulation i daarlig 38 smag’, for året før var Christensen han i øvrigt havde den blandede for Opera og champagne draget over til Guds eget land for nøjelse at stifte bekendtskab med Benjamin Christensen ville oprinde der at fortsætte sin karriere. -

Kosmorama 7 Det Danske Filmmuseums Tidsskrift 4

KOSMORAMA 7 DET DANSKE FILMMUSEUMS TIDSSKRIFT 4. APRIL 1955 Fra det spanske afsnit af ,,Blade af Satans bog” : Hallander Hellemann som Don Gomez. DANSK FILM I 50 ÅR Dette specialnummer af „Kosmorama" er helliget den danske films historie. 10 film skribenter — Marguerite Engberg, Erik S. Saxtorpk, Jørgen Stegelmann, Ib Monty, Werner Pedersen, Theodor Christensen, I. C. Lauritzen, Bjørn Rasmussen, Bent Petersen og Erik Ul~ richsen — behandler hver en 5-årig periode i tiden 1905—55. Inddelingen er foretaget af praktiske grunde og „dækker" ikke helt filmhistorisk, og naturligvis er der ikke op nået absolut „egalitet", da så mange forskellige ytrer sig, men vi håber dog, at denne danske filmhistorie en miniature kan være af værdi som oversigt. selskaber at dukke op. Søren Nielsens Blafrende dekorationer sensationsfilm (Biorama-film) nåede dog aldrig op på højde med Ole Olsens, det 1905-10 af Marguerite Engberg gjorde derimod de film, som det århusi anske udlejningsselskab Fotorama i 1909 begyndte at optage. Fotorama speciali I 1905 åbnede Ole Olsen sin biograf serede sig fra begyndelsen i historiske i Vimmelskaftet 47, efter at Constantin film. Den første film var „Den lille Philips en året i forvejen havde åbnet Hornblæser44, og senere fulgte f. eks. en „Kosmorama44, Danmarks første biograf. Holger Danske-film. Da konkurrencen I 1906 grundlagde Olsen Nordisk Films omkring 1911 blev Ole Olsen for nær Kompagni, Danmarks første filmselskab. gående, købte han blot de bedste in Peter Elfelt, hoffotografen, havde ganske struktører og skuespillere over til sig. vist allerede fra 1896 optaget reportage film af både kongehusets og borgerska På Nordisk arbejdede man videre med bets dagligliv og indspillet den første de samme genrer. -

Realizing the Witch

Richard Baxstrom & Todd Meyers Realizing the Witch Science, Cinema, and the Mastery of the Invisible Richard Baxstrom & Todd Meyers Realizing the Witch Science, Cinema, and the Mastery of the Invisible Realizing the Witch StefanosS Geroulanos and Todd Meyers, series editors Realizing the Witch Science, Cinema, and the Mastery of the Invisible Richard Baxstrom and Todd Meyers Fordham University Press New York 2016 Frontispiece: Svensk Filmindustri poster for Häxan (1922) Copyright © 2016 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means— electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other— except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persis- tence or accuracy of URLs for external or third- party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Visit us online at www .fordhampress . com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Baxstrom, Richard. Realizing the witch : science, cinema, and the mastery of the invisible / Richard Baxstrom, Todd Meyers. pages cm. — (Forms of living) Includes bibliographical references and index. Includes lmography. ISBN 978-0-8232-6824-5 (hardback) — ISBN 978-0-8232-6825-2 (paper) 1. Häxan (Motion picture) 2. Witchcraft—Europe— History. 3. Witches—Europe. 4. Christensen, Benjamin, 1879–1959. -

Witchcraft Through the Ages

Witchcraft through the Ages Thursday, October 31, 2013 ~ Grand Illusion Cinema, Seattle ~ Presented by The Sprocket Society Originally released by Svensk Filmindustri as Häxan (Sweden) and Heksen (Denmark), both translate as The Witch. Premiered on September 18, 1922 in Stockholm, Sweden; and November 7, 1922 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Retitled in 1926 as La sorcellerie à travers les âges (“Witchcraft through the Ages”) for its French premiere. Re-released in 1941 with a musical soundtrack by Emil Rosen, and a sound introduction by Benjamin Christensen. Written and Directed by Benjamin Christensen 1968 English sound version: Director of Photography: Johan Ankerstjerne Produced by Antony Balch Art Director: Richard Louw Narrated by William S. Burroughs Edited by Edla Hansen Musical score composed by Daniel Humair Original score by Jacob Gade Recorded at Studios Europasoner (Paris) Produced by Charles Magnusson 1968 score performed by Jean-Luc Ponty (violin), Michel Portal (flute), Bernard Lubat (piano organ), Guy Pedersen (double bass), and Daniel Humair (percussion). Danish-born Benjamin Christensen (1879-1959) had largely responsible for the groundbreaking quality of originally planned this to be the first in a trilogy about Swedish film, nurturing the likes of Victor Sjöström. superstition throughout history, but the intense Christensen persuaded him to buy and equip an entire controversy Häxan caused upon its release meant that studio for the production. After extensive preparation Helgeninde (The Woman Saint) and Ånder (Spirits) and casting, filming began at last – in utmost secrecy – would never be made. A review of the Danish premiere in late winter 1921, continuing well into the following called it “unvarnished perversity” and demanded October. -

Otto Lington-Disko-Text-2

Efter sit udenlandsophold siden Danmarks Tournéens afslutning - begynder Otto Lington den 1. september 1931 at spille hos Pagh i Frederiksbergsgade. Derefter fra november hos Ritz. Den 20. december 1931 medvirker hans Café Ritz orkester i Politikens 24. Julekoncert i Odd Fel- low Palæet. Fr. Schnedler-Petersen dirigerer Københavns Filharmoniske Orkester og der er mange gode medvirkende: Johannes Meyer, Hans Hartvig Seedorff Pedersen, Osvald Helmuth, Opera- sanger Einar Larson, Statsoperaen, Stockholm, Johannes Poulsen, Valdemar Møller og Elith Pio alle tre fra Det kgl. Teater med en scene fra Kaj Munks ”Cant”, Carl Alstrup med en scene fra Soldat Svejk, Liva og Arne Weel, Co-Optimisterne og endelig en Lander ballet – danset af Harald Lander og Ulla Poulsen m.fl. - med musikken komponeret og dirigeret af Emil Reesen. Otto Ling- tons Jazz-Band fra Ritz spillede: a) Symfonisk Arrangement (af Wilfred Kjær) af Operetten ”Victoria og hendes Husar” b) Orkestret akkompagnerer Fru Solveig og Hr. Hans W. Petersen til en Sang- og Danseduet af ”Pepina” I pausen spillede The Amateur Dances Jazz-Band dirigeret af Hr. Børge Rosenwald. Otto Lingtons ”Jazz-Band fra Ritz” formentlig fra åbningen i november 1931 fra venstre: Vilfred Kjær, piano - Otto Lington, dirigent og violin – Albert Rasmussen, trommer - Eigil Scheuer, saxofon – Knud Bentzen, saxofon - Poul Christiansen, saxofon - Olof Carlson, trompet – Holger Nathansohn, saxofon Måske har hr. kapelmester Schnedler-Petersen og hans unge kollega Otto Lington, fået sig en snak om jazz eller ej i pausen? 57 I Danmark havde man eksperimenteret med lyd til filmen helt fra 1923 hvor de to pionerer og op- findere Axel Petersen og Arnold Poulsen viste flere små film med lyd. -

Nordic Film Cultures and Cinemas of Elsewhere S

AND ARNE LUNDE STENPORT WESTERSTAHL ANNA EDITED BY Traditions in World Cinema General Editors: Linda Badley and R. Barton Palmer Founding Editor: Steven Jay Schneider This series introduces diverse and fascinating movements in world cinema. Each volume concentrates on a set of films from a different national, regional or, in some cases, cross-cultural cinema which constitute a particular tradition. NORDIC FILM CULTURES AND CINEMAS OF ELSEWHERE EDITED BY ANNA WESTERSTAHL STENPORT AND ARNE LUNDE ‘Jamie Steele skillfully combines an impressively researched industrial study with attentive close AND CINEMAS OF ELSEWHERE readings of selected works by the best-known francophone Belgian directors. The book fills a major NORDIC FILM CULTURES gap in scholarship on francophone Belgian cinema and insightfully contributes to a growing body of NORDIC FILM CULTURES work on regional and transnational French-language cinematic productions.’ AND CINEMAS OF ELSEWHERE Michael Gott, University of Cincinnati Considers transnational, national and regional concepts within contemporary EDITED BY ANNA WESTERSTAHL STENPORT AND ARNE LUNDE francophone Belgian cinema Francophone Belgian Cinema provides an original critical analysis of filmmaking in an oft-neglected ‘national’ and regional cinema. The book draws key distinctions between the local, regional, national and transnational conceptual approaches in both representational and industrial terms. Alongside the Dardenne brothers, this book considers four promising Francophone Belgian filmmakers who have received limited critical attention in academic publications on contemporary European cinema: Joachim Lafosse, Olivier Masset-Depasse, Lucas Belvaux and Bouli Lanners. Exploring these filmmakers’ themes of post-industrialism, paternalism, the fractured nuclear family and spatial dynamics, as well as their work in the more commercial road movie and polar genres, Jamie Steele analyses their stylistic continuities and filiation. -

Peter Von Baghin Elokuvakirjasto

PETER VON BAGHIN ELOKUVAKIRJASTO Luettelon laati Petteri Paksuniemi 2014 ja sitä on täydentänyt Antti Alanen 2018 2018 2 Sisällys PETER VON BAGHIN ELOKUVAKIRJASTO .................................................................................................................... 1 Antti Alanen: Peter von Baghin ammattikirjasto .................................................................................................... 4 Peter von Bagh: Kirjastoni ̶ Eletyn elämän muuan varjo ....................................................................................... 6 ELOKUVANTEKIJÄT HENKILÖITTÄIN ........................................................................................................................ 9 OHJAAJA-ANTOLOGIAT ....................................................................................................................................... 116 NÄYTTELIJÄT / FILMITÄHDET, NÄYTTELEMINEN................................................................................................. 118 KUVA JA ÄÄNI ..................................................................................................................................................... 121 KÄSIKIRJOITTAMINEN, KÄSIKIRJOITTAJAT, KIRJALLISUUS & ELOKUVA ............................................................... 122 LAVASTUS, ARKKITEHTUURI, MUOTISUUNNITTELU ........................................................................................... 123 ELOKUVAN HISTORIA YLEISESTI ......................................................................................................................... -

Scoring Häxan

University of Amsterdam Faculty of Humanities MA Heritage Studies: Preservation & Presentation of the Moving Image (RE)SCORING HÄXAN Supervisor: Annet Dekker Second Reader: Eef Masson Thesis of: Fabrizio D’Alessio E-mail: [email protected] Student Number: 11311487 Amsterdam, 4 February 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 CHAPTER 1: SILENT FILM WITH MUSIC, A TRADITION OF NOVELTY 6 1.1 A theoretical gap between film and music 7 Looking for the added value 7 Cinema as event 9 1.2 (Re)scoring silent films, a new-old practice 11 Historically-accurate versions 12 Novel versions 13 CHAPTER 2: (RE)SCORING HÄXAN 15 2.1 Häxan, what is it? 15 A tormented reception 16 2.2 The phantom ‘first night’ of the Witch 19 Authentic conjectures 19 Back in time through DVD’s multiplicity 21 Surrounded by sounds in a Home Theatre 22 2.3 How does the Devil talk? 24 Into the gap 24 The voice of the Devil 25 Cult as event 27 2.4 A kiss of life for the Witch 30 Hypermediated performances 31 Songs for synchresis 32 Electronic sounds for contemporary audiences 33 CONCLUSION 34 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 2 INTRODUCTION The practice of adding music to a silent film is as long as cinema. Up until the standardization that came with the introduction of sound, music for the silent film was “an independent, ever-changing accompaniment” (Marks 6). From theater to theater, many different musicians worked on the same single silent picture, the form and style of accompaniment would vary from country to country, even theatre to theatre, and evolve and change over time.