Scoring Häxan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidade Estadual De Ponta-Grossa Pró-Reitoria De Pesquisa E Pós-Graduação Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Linguagem, Identidade E Subjetividade

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE PONTA-GROSSA PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LINGUAGEM, IDENTIDADE E SUBJETIVIDADE ANDERSON COSTA UMA REVOLUÇÃO PELO ACASO OU O CUT-UP NO CINEMA UNDERGROUND DOS ANOS 60 PONTA-GROSSA – PARANÁ 2013 ANDERSON COSTA UMA REVOLUÇÃO PELO ACASO OU O CUT-UP NO CINEMA UNDERGROUND DOS ANOS 60 Dissertação apresentada para a obtenção do título de Mestre na Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa. Área de Linguagem, Identidade e Subjetividade. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Antonio João Teixeira PONTA-GROSSA – PARANÁ 2013 Ficha Catalográfica Elaborada pelo Setor de Tratamento da Informação BICEN/UEPG Costa, Anderson C843 Uma revolução pelo acaso ou o cut-up no cinema underground dos anos 60/ Anderson Costa. Ponta Grossa, 2013. 123f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Linguagem, Identidade e Subjetividade - Área de Concentração: Linguagem, Identidade e Subjetividade), Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Antonio João Teixeira. 1.Burroughs. 2.Cut-Up Films. 3.Beatniks. 4.Cinema. I.Teixeira, Antonio João. II. Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa. Mestrado em Linguagem, Identidade e Subjetividade. III. T. CDD: 410 ANDERSON COSTA UMA REVOLUÇÃO PELO ACASO OU O CUT-UP NO CINEMA UNDERGROUND DOS ANOS 60 Dissertação apresentada para obtenção do título de Mestre na Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa, Área de Linguagem, Identidade e Subjetividade. Ponta Grossa, 02 de julho de 2013. Professor Dr. Antonio João Teixeira Doutor em Letras (Inglês e Literatura Correspondente) Universidade Estadual de Ponta-Grossa Professor Dr. José Soares Gatti Júnior Doutor em Cinema Studies Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná Professora Dra. Silvana Oliveira Doutora em Teoria e História Literária Universidade Estadual de Ponta Grossa AGRADECIMENTOS Quero agradecer, especialmente, a meu orientador, professor Doutor Antonio João Teixeira, pelas valiosas contribuições e pela imensa paciência que teve com este orientando relapso. -

Towers Open Fire (1963). Foto: Antony Balch Films

Towers Open Fire (1963). Foto: Antony Balch Films. 56 Storm studiet – panoreringer i det grå rum Antony Balch, William S. Burroughs, cut-up og flm Balthazar Lars Movin I sin klumme i New York-magasinet Te Art Newspaper opremsede kunstkritikeren Adrian Dannatt i oktober 2001 en række eksempler på, hvordan Manhattans kunstverden var blevet påvirket af terroran- grebet mod World Trade Center måneden forinden. Hårdest ramt var naturligvis de kunstnere, som havde atelier i selve Twin Towers. Og dernæst var der dem, som boede eller arbejdede i Tribeca-området eller endnu længere sydpå – samt de mange gallerier og andre typer kunstin- stitutioner, som havde adresse i samme område. Alle blev de påvirket i et eller andet omfang. Udstillinger og projekter blev afyst eller udsat. Kunstnere og institutioner måtte fytte, midlertidigt eller permanent. Det kan godt være, at der fandtes vildfarne sjæle, som senere ville lufte muligheden af, at begivenhederne den 11. september 2001 i et vist perspektiv kunne betragtes som et apokalyptisk kunstværk med en hidtil uset efekt. Men i dagene og ugerne efter 9/11 kunne ingen være i tvivl om, at der først og fremmest var tale om en yderst virkelig hændelse med, om ikke apokalyptiske, så dog ganske seriøse konse- kvenser. Der var kort sagt ikke meget at grine ad, da Dannatt forsøgte at danne sig et overblik over, hvad den nye verdensorden ville betyde 57 for hans stofområde. Og som for at slutte sine refeksioner i et mindre dystert leje rundede han af med en lille kuriøs anekdote, der skulle de- monstrere, at kunstnerne ikke var ene om at lide under eftervirkninger- ne af angrebet. -

San Francisco Cinematheque Program Notes

titled "The situationists and ne\ politics and art" appeared i iniste#ll (October 1967). Hebe, ve have stuck principally to subv^ m of forms, categories inherited f ; prini San Francisco Cinematheque entury that 1990 Program Notes nt the^ don by means which proceed wi It is not however a matter of i 'hich we have made battle on the passing of philosophy, the realize I of politics; it is a matter of takin, : of our journal, in areas where i le then outlines a new offensive a San Francisco Cinematheque 1990 Program Notes Editor: Kurt Easterwood Productimi and Layout: Laura Poitras Production Assistants: Mai-Lin Cheng Emily Cronbach Jennifer Durrani Written and Researctied by: Bruce Cooper Emily Cronbach Kurt Easterwood Susanne Fairfax Matt Fein Crosby McCIoy Eric S. Theise Don Walker material © Copyright 1991 by the San Francisco Cinematheque, a project of the Foundation for Art in Cinema. No may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. All individual essays © to the individual authors. San Francisco Cinematheque Foundation for Art in Cinema 480 Potrero Avenue San Francisco, CA 94110 (415)558-8129 San Francisco Cinematheque, 1990-91: Staff: Steve Anker, Artistic Director David Gerstein, Executive Director Laura Poitras. Program Coordinator Board of Directors: Eric S. Theise, President Sally Allen Lynn Kirby (through January 1991) Janis Crystal Lipzin (through May 1990) Lynne Sachs Scott Stark (through May 1991) Scott Taylor Susan Vigil Contents Introduction v 1990 Program Notes 1 Film and Video Maker Index 1 13 Title Index 117 Introduction The San Francisco Cinematheque provides program notes at our screenings as a regular feature of our exhibition activities. -

William S. Burroughs: Pictographic Coordinates

William S. Burroughs: Pictographic Coordinates ANTONIO JOSÉ BONOME GARCÍA Universidade da Coruña (Spain) Abstract La apropiación y reorganización de contenidos audiovisuales preexistentes es un hecho cotidiano en las actuales tecnologías de la información. El objetivo de esta comunicación es trazar dichas estrategias en los métodos de producción del escritor William S. Burroughs, que durante los años 60 produce seis mil páginas de escritura experimental mediante el método cut-up. Burroughs cuestiona el concepto de autor cuando se apropia de textos de otros escritores y los recorta, reordena, y combina con su propia escritura en un nuevo contexto, reintroduciendo una aleatoriedad estancada hasta entonces en automatismos y cadáveres exquisitos. Con Burroughs, la palabra pasa a ser un material tangible y táctil, mientras que el texto deviene algo contingente y múltiple. Burroughs produce diferentes versiones de sus textos integrándolos en un archivo multimedia, al que recurre para alterar radicalmente posteriores reediciones de sus obras. En la intertextualidad del archivo y sus subproductos descubrimos frecuentes reflexiones sobre la construcción de unos textos que son accesibles desde cualquier punto de entrada. Hay tres factores cruciales en las tácticas interdisciplinares de Burroughs: los procesos de percepción, cognición y recepción. Burroughs extiende su sistema nervioso a través de mecanismos de grabación y reproducción para expresar la simultaneidad de estímulos que asedian al sujeto cotidianamente. También se apropia de imágenes y textos que reordena en retículas y columnas triples, legibles en cualquier dirección y sentido. La parataxis es una táctica recurrente en su particular sistema semiótico, que compromete al lector como productor de sentido. Los cuadernos y collages resultantes erosionan el límite entre literatura y artes plásticas. -

Beat Generation November 2016

Saturday 26.11.2016 – Sunday 30.04.2017 C Press Release Beat Generation November 2016 ZKM_Lichthof 8+9 Beat Generation Exhibition __ Duration of exhibition Sat, Nov. 26, 2016 - The exhibition will open on Friday, November 25, 2016 at 7 p.m.. The Sun, Apr. 30, 2017 press conference will be held on Thursday, November 24, 2016 at 11 a.m.. Venue __ ZKM_Atrium 8+9 The ZKM | Karlsruhe will be the second stage of the Beat Generation exhibition after the Centre Pompidou in Paris. In the Press contact Dominika Szope last few years, the ZKM has dedicated a number of major Head of Press & Public Relations Tel.: +49(0)721 / 8100 – 1220 exhibitions to the leading figures of the Beat Generation, such as William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg. In this new Regina Hock Press & Public Relations exhibition, an overview of the literary and artistic movement, Tel.: +49 (0)721 / 8100 – 1821 which was created at the end of the 1940s, will now be E-mail: [email protected] provided for the first time. If “beatniks” were viewed back then www.zkm.de/presse as subversive rebels, they are now perceived as actors in one of ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe th the most important cultural directions of the 20 century. Lorenzstraße 19 76135 Karlsruhe The Beat Generation was a literary and artistic movement that arose at the end of the Forties in the USA after the Second World War and in the early days of the Cold War. It scandalized the puritanical America of the ZKM sponsors McCarthy era, heralding the cultural and sexual revolution of the Sixties and the lifestyle of the younger generation. -

Benjamin Christensen Ckery" (Lon Chaney), „Hawk’S Nest" (Milton Silis), „The Haunted House" {C Hest Er Conk- 28

„The Devil’s Circus" (Norma Shearer), „Mo- Benjamin Christensen ckery" (Lon Chaney), „Hawk’s Nest" (Milton Silis), „The Haunted House" {C hest er Conk- 28. 9. 1879 - 1. 4. 1959 lin), „House of Horror" (Thelma Todd) og „Seven Footprints to Satan" (også Thelma Todd) — Benjamin Christensen selv satte dem ikke højt, men der skal nok være sære og in Benjamin Christensen, der døde den 1. april teressante effekter i flere af dem, og forhåbent 79 år gammel, var ikke glemt. Det Danske lig er de ikke sporløst forsvundet. Filmmuseum har for ikke så længe siden vist Efter „Seven Footprints to Satan" fulgte en hans debutfilm „Det hemmelighedsfulde X“ tiårig pause, så kom instruktøren igen i Dan (1913) og den af Dreyer iscenesatte „Michael“ mark, hvor han iscenesatte „Skilsmissens (1924), i hvilken Benjamin Christensen spiller Børn", „Barnet", „Gaa med mig hjem" og hovedrollen, og i „Kosmorama 7“ bragtes et „Damen med de lyse Handsker", bedst var de index over hans film. to første, værst den sidste, der satte et noget Den indgående analyse af Benjamin Chri pinligt punktum for Benjamin Christensens stensens værker, som endnu ikke er skrevet, hå instruktørkarriére. ber vi senere at kunne bringe i „Kosmorama“. Benjamin Christensens evner burde have Den afdøde instruktør fortjener den, han var ført ham ind i en endnu mere imposant kar en pioner, og han skabte en stor film, den be riere, men filmproducenterne er mildest talt rømte „Heksen“. ikke altid ideelle mæcener. Imidlertid var - Hans væsentligste pionerindsats i hine år, da og er - Christensen en af de få internationalt ingen med sikkerhed kunne sige, om filmen berømte danske filminstruktører, og i hvert ville udvikle sig til en kunstart, var den op fald „Heksen" er af varig værdi. -

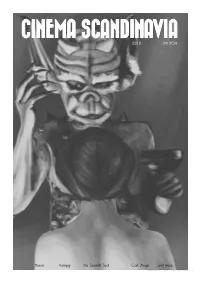

Cinema Scandinavia Issue 2 May 2014 Compressed

CINEMA SCANDINAVIA issue 2 may 2014 Haxan Vampyr The Seventh Seal Carl Dreyer ....and more CINEMA SCANDINAVIA PB CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 1 COVER ART http://jastyoot.deviantart.com/ IN THIS ISSUE Editorial News Haxan and Vampyr Death in the Seventh Seal The Dream of Allan Grey Carl Dreyer Blad af Satans Bog Across the Pond Ordet Released this Month Festivals in May More Information Call for Papers CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 THE PARSONS WIDOW CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 2 CINEMA SCANDINAVIA 3 Terje Vigen The Outlaw and his Wife WELCOME Welcome to the second issue of Cinema Scandinavia. This issue looks at the early Scandinavian cinema. Let me provide a brief overview of early Nordic film. Film came to the region in the late 1890s, and movies began to appear in the early 1900s. Danish cinema pioneer Peter Elfelt was the first Dane to make a film, and in the years 1896 through to 1912 he made over 200 films documenting Danish life. His first film was titled Kørsel med Grønlandske Hunde (Travelling with Greenlandic Dogs). During the silent era, Denmark and Sweden were the two biggest Nordic countries on the cinema stage. In Sweden, the greatest directors of the silent era were Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. Sjöström’s films often made poetic use of the Nordic landscape and played great part in developing powerful studies of character and emotion. Great artistic merit was also found in early Danish cinema. The period around the 1910’s was known as the ‘Golden Age’ of cinema in Denmark, and understandably so. With the increasing length of films there was a growing artistic awareness, which can be seen in Afgrunden (The Abyss, 1910). -

Download As Pdf

Journal of Historical Fic�ons 3:1 2020 Editorial: ‘Historical Fic�ons’ When the World Changes Julie�e Harrisson John Fowles’s ‘Manchester baby’: forms of radicalism in A Maggot Julie Depriester Troubling Portrayals: Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1922), Documentary Form, and the Ques�on of Histor(iography) Erica Tortolani Editors: Natasha Alden – Alison Baker – Jacobus Bracker – Benjamin Dodds – Dorothea Flothow – Catherine Padmore – Yasemin Sahin – Julie�e Harrisson The Journal of Historical Fic�ons 3:1 2020 Editor: Dr Julie�e Harrisson, Newman University, UK Faculty of Arts, Society and Professional Studies Newman University Genners Lane Bartley Green, Birmingham B32 3NT United Kingdom Co-Editors: Dr Natasha Alden, Aberystwyth University; Alison Baker, University of East London; Jacobus Bracker, University of Hamburg; Dr Benjamin Dodds, Florida State University; Dr Dorothea Flothow, University of Salzburg; Dr Catherine Padmore, La Trobe University; Dr Yasemin Sahin, Karaman University. Advisory Board: Dr Jerome de Groot, University of Manchester Nicola Griffith Dr Gregory Hampton, Howard University Professor Farah Mendlesohn Professor Fiona Price, University of Chichester Professor Mar�na Seifert, University of Hamburg Professor Diana Wallace, University of South Wales ISSN 2514-2089 The journal is online available in Open Access at historicalfic�onsjournal.org © Crea�ve Commons License: A�ribu�on-NonCommercial-NoDeriva�ves 4.0 Interna�onal (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) Birmingham 2020 Contents Editorial: ‘Historical Fictions’ When the World Changes -

Expanded Media March 2012

March 24 – August 12, 2012 Press Information the name is BURROUGHS – Expanded Media March 2012 Such works as “Naked Lunch” or “The Soft Machine” are what made the name is BURROUGHS – William S. Burroughs (1914-1997) world famous as an author. Far less Expanded Media known, by contrast, is that Burroughs, as a cross-media artist, also produced a comprehensive, varied body of work that no less Location experiments with audio tape, film and photography as it does with ZKM | Museum of Contemporary Art painting and collages. The comprehensive exhibition “the name is BURROUGHS – expanded media” presents the author’s artistic Press Discussion output in Germany for the first time; it examines the multiple Thurs, March 22, 2012, 11 a.m. at the ZKM | Museum affiliations between literary and experimental image production, of Contemporary Art further augmenting the image by way of the representation of Opening “collaborations” Burroughs produced in association with other Fri, March 23, 2012, artists. The exhibition gains additional appeal thanks to a series of 7 p.m. in the ZKM_Foyer works by contemporary international artists who each make Duration unambiguous reference to Burrough’s writings and his method of March 24 – August 12, 2012 “expanded media”, and thus, from a present-day perspective, sound out the individual pictorial potential. Press Contact Dominika Szope Head of Department Press and The exhibition’s goal is to make tangible, in review and for the first time Public Relations Tel: 0721 / 8100 – 1220 within Europe on such a scale, the visionary volatility of William S. Burroughs’ literary output while at the same time showing the impact of his Denise Rothdiener ideas and philosophy on a wider network of authors, musicians, Department Press Tel: 0721 / 8100 – 1821 composers, painters, photographers, video artists and filmmakers. -

Benjamin Christensen's Häxan

Troubling Portrayals: Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1922), Documentary Form, and the Question of Histor(iography) Erica Tortolani, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Abstract: This essay discusses the 1922 Benjamin Christensen film, Häxan (or, Witchcraft through the Ages), and ways in which it complicates genre, narrative, and historical representation. Combining historical facts backed by real artefacts from the era with narrative reenactments inserted throughout, Häxan blurs the lines between reality and fiction, history and storytelling, which, at first glance, de-legitimizes its positioning as a documentary film, and thereby undermines its historical representations. To the contrary, Häxan should instead be placed in a different category of nonfiction, one that is not bound by the limitations of documentary filmmaking as we have come to know it, in that it provides a rich, multifaceted account of the medieval era that must not be ignored. Offering a view of history that accounts for social, cultural, religious, and medical perspectives, the film is in fact a representation of the past that challenges dominant notions of witchcraft in the Middle Ages and beyond, and can thus be regarded as an important contribution to the historiography of the period. Moreover, the film makes important (and rather troubling) claims regarding the oppression of women during this era, which is introduced towards the end of my analysis. Keywords: Silent film, Benjamin Christensen, witchcraft, documentary, history, psychoanalysis In a 2016 interview with the movie review website SlashFilm, director Robert Eggers discussed some major influences for his horror film of that year, The Witch, citing cinematic classics including Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers (1972) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980). -

'Der Er Jo Altid En Middel- Maadighed Ved Haanden, Når Geniets Stol

FILMEN I 100 ÅR ‘Der er jo altid en Middel- maadighed ved Haanden, når Geniets Stol bliver tom’ ...skriver Benjamin Christensen i sin novellesamling af Maren Pust 1Hollywood Skæbner’. Den danske instruktør prøvede ikke at være bitter over den medfart, han fik i filmbyen, var bidt af en gal ‘Spectator’ (såle men det var svært, især fordi han faktisk havde fortjent des underskrev han sig) og derfor bi bedre. Det Danske Filmmuseum viser i det første pro drog i pressen med polemiske ind gram i det nye dr en sene med 11 af hans film. læg om filmkunstens beskaffenhed. Han roterer sikkert i sin urne, nu da jeg sidder og citerer ham for den rfvinv er er sagt mere end nok om giver sig udslag i film af Eleanor h o ld n in g til amerikansk film, han 1 ^ / Nordisk og Laus film, men Glyn typen. Maa vi bede om virke skiftede nemlig mening sidenhen. jeg synes, at der er grund til at nævne lige talenter, instruerede af dygtige Men det er egentlig lidt interessant, Benjamin Christensens store indsats og litterært bevandrede instruktører, at han fremhævede Benjamin Chri (...) Film er gøgl og ikke kunst saa- i film, hvis indhold og handling er stensen som den person, der mulig længe, man ikke kommer bort fra taget ud af livet, og som følgelig er gjorde, at filmen kunne udvikle sig den amerikanske spekulation i den troværdige.” - Sådan skrev min beds til en kunstart fremfor blot at være daarlige smag, hvilken spekulation tefar i 1926, da han som stud.mag. ‘amerikansk spekulation i daarlig 38 smag’, for året før var Christensen han i øvrigt havde den blandede for Opera og champagne draget over til Guds eget land for nøjelse at stifte bekendtskab med Benjamin Christensen ville oprinde der at fortsætte sin karriere. -

Retaking the Universe

Schn-FM.qxd 3/27/04 11:25 AM Page iii Retaking the Universe William S. Burroughs in the Age of Globalization Edited by Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh Schn-FM.qxd 3/27/04 11:25 AM Page iv First published 2004 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA 22883 Quicksilver Drive, Sterling, VA 20166–2012, USA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh 2004 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7453 2082 1 hardback ISBN 0 7453 2081 3 paperback Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Retaking the Universe: William S. Burroughs in the Age of Globalization/ edited by Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-7453-2082-1 (hbk.)—ISBN 0-7453-2081-3 (pbk.) 1. Burroughs, William S., 1914—Criticism and interpretation 2. Homosexuality and literature—United States—History—20th century. 3. Sexual orientation in literature. 4. Beat generation in literature. 5. Narcotic habit in literature. I. Schneiderman, Davis. II. Walsh, Philip, 1965– PS3552.U75Z835 2004 813Ј.54—dc22 2003025963 10987654321 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services, Fortescue, Sidmouth, EX10 9QG, England Typeset from disk by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd, India Printed and bound in the European Union by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne, England Schn-FM.qxd 3/27/04 11:25 AM Page v Contents List of Abbreviations vii Acknowledgments x Foreword xi —Jennie Skerl Introduction: Millions of People Reading the Same Words —Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh 1 Part I Theoretical Depositions 1.