Desert Encounters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life of Saint Paul of the Cross Founder of the Congregation of the Cross and Passion

The Life of Saint Paul of the Cross Founder of the Congregation of the Cross and Passion 1694-1775 Volume 1 – 1694-1741 Father Louis Therese of Jesus Agonizing, C.P. 1873 Fr. Simon Woods, C.P. (Translated from the third French Edition) 1959 (INDEX TO VOLUME ONE ON FINAL PAGES) DEDICATION to HIS EMINENCE FERDINAND CARDINAL DONNET Archbishop of Bordeaux Your Eminence, The Life of Saint Paul of the Cross, which it is my privilege to dedicate to you, may rightfully be called your very own. Without your Eminence the work may not have been completed, and I may never have realized the idea that I had in mind for a very long time. It is then the humble fruit of a tree planted by your own hands in the vineyard confided to your care by the Heavenly Father. It was when your Eminence was in Rome for the Beatification of our holy Founder that you obtained from His Holiness Pope Pius IX the sons of Saint Paul of the Cross for your Archdiocese… And, if this little family was welcome and took its humble beginnings in the fruitful soil of France under your protection and guidance, is it not due to your paternal interest and initiative? Soon, it is true, a learned and zealous clergy imitated your zeal; but in those days of supreme struggle, of unceasing conflict against the rights of the Church, your Eminence realized that it is necessary that zeal be united with learning, especially when the war “against the Lord and his Christ” becomes so universal. -

Some Striking

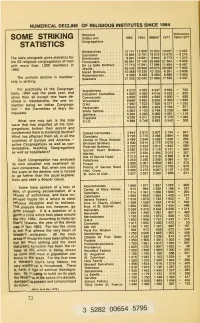

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

A Passionist Friendship: Barnabas Ahern and Thomas Merton

17 A Passionist Friendship: Barnabas Ahern and Thomas Merton By John Collins Passionist Father Barnabas M. Ahern was one of the most significant American Catholic scripture scholars of the mid-twentieth century, during the years leading up to and following the Second Vatican Council. Through correspondence and occasional encounters, Thomas Merton and Father Ahern developed a mutually beneficial relationship in which Ahern provided Merton with valuable advice not only on scripture but on his works in progress and even his personal life, while Merton was enlisted for a time by Ahern to contribute his literary expertise to the project of the new American Catholic translation of the Bible. The extant correspondence between Merton and Ahern is one-sided; only a single letter from Merton to Ahern survives, from January 22, 1953;1 a total of twenty-one letters from Ahern to Merton, from April 10, 1950 through April 8, 1956, are preserved in the archives of the Thomas Merton Center at Bellarmine University.2 During the period when Ahern was teaching seminarians at the Passionist monastery in Louisville, KY, from 1959 through 1962, he also gave lectures on scripture at the Abbey of Gethsemani, where he and Merton would meet on occasion.3 An examination of the Merton/Ahern correspondence and related materials provides significant insights into Merton’s concerns and interests during the period, though much of the information has to be inferred from Ahern’s responses; while the relationship was not an intimate one, and continued to be marked by a certain formality on Ahern’s part throughout the correspondence, it was an important one for Merton during a period of his life marked both by spiritual restlessness and spiritual growth. -

“Beautiful Solitude Yet Within Easy Access of the City”

Volume 14 Issue 2 Spring 2007 The Passionists in Kingsbridge and Riverdale, Bronx, New York Neighborhood and Architecture: Cardinal Spellman Retreat House 1967 to 2007 This issue of the Passionist Heritage Newsletter celebrates Passionist history in the Bronx from 1904 to 1967. The first article revolves around conflicting definitions of Passionist preaching, prayer, and solitude; their buying and selling of choice real estate in the Bronx; and the participation of Passionists in local Riverdale neighborhood planning. The other articles recall the first person memories of Father Columkille Regan, C.P. and Brother Conrad Federspiel, C.P. as Cardinal Spellman Retreat House was being constructed and before it was dedicated in 1967. Combined, their insights offer readers a new historical perspective on the immediate and long-lasting influence of architect Brother Cajetan Baumann, O.F.M. on retreat ministry, maintenance, and budget operations. —Editor “Beautiful Solitude Yet Within Easy More on the Kingsbridge location can be found in the New York Times. On December 11, 1920, it was Access of the City” reported the Passionists purchased about four acres of land for $100,000. This included the “Eames house on By Father Rob Carbonneau C.P. the Claflin estate.” A July 25, 1923, article told how the exempt status of the Passionists and other organizations At first glance, people are quite amazed by the bucolic were being investigated in a city-wide sinking fund and spiritual beauty of the modern Cardinal Spellman project used to insure redemption of debt. On August 7, Retreat House operated by the Passionists at 5801 1924, a caption read: “Passionist Fathers Acquire Large Palisade Avenue in the Bronx, New York. -

CCD Signatories Listed by State

Catholic Climate Declaration Signatories Listed by State 806 as of November 13, 2019 Alabama ........................................................ 2 North Carolina............................................ 22 Alaska ........................................................... 2 Ohio ........................................................... 22 Arizona ......................................................... 2 Oklahoma ................................................... 24 Arkansas ....................................................... 2 Oregon ....................................................... 25 California ...................................................... 2 Pennsylvania............................................... 25 Colorado ....................................................... 4 Puerto Rico................................................. 27 District of Columbia ..................................... 5 Rhode Island .............................................. 27 Florida ..........................................................6 South Carolina ........................................... 27 Georgia .........................................................6 South Dakota ............................................. 27 Illinois .......................................................... 7 Tennessee ................................................... 28 Indiana .........................................................8 Texas .......................................................... 28 Iowa ..............................................................9 -

Remembering with Gratitude

The Passionist Nuns of Saint Joseph Monastery in the Diocese of Owensboro KY Lent 2020 ear Family & Friends, D Greetings and Blessed Lent to each and all of you! It is always our joy to come to you with the latest news at the monastery. This year, we begin celebrations of an awesome convergence of four Passionist an- niversaries beginning with the Tricentennial celebration in November of the inspiration of our Passionist charism — see page 6 for details. It is a time to dig back to the roots of our Congregation and to give thanks for the witness of those who have faithfully lived and passed on the flame of our Passionist life and charism. May we, too, faithfully im- part that flame! Please pray for our new members, and for more vocations who will carry the flame to the next generation. Our Sr. Lucia Marie just renewed her temporary vows; God- willing, 2020 will also see the vow renewals of her two juniorate companions. Sr. Miri- am Esther received the Holy Habit and her new name on our Founder’s feast, October 20, 2019, and two young ladies continue in our aspirancy program. God is at work! Witnessing and surrendering to God’s plan for our community is ever awesome and exciting….and also ever a lesson in trust! On page 7 you will see that we have embarked on a construction/renovation pro- ject and are putting on a new roof! His provi- dence ever watches over us with the help of YOUR spiritual and material support. Please consider helping us financially as we contin- ue to hold you in our daily grateful prayers, here at the Foot of the Cross! Gratefully in Christ our Redeemer, Mother John Mary and the Monastic Community Remembering With Gratitude.. -

Master List of Catholic Groups

Help Pages to Native Catholic Record Guides See User Guide for help on interpreting entries MASTER LIST OF CATHOLIC GROUPS new2003; rev2006-2017 These Catholic Church agencies and affiliated Catholic organizations have had past involvement in evangelization and ministry to Native Americans in the United States. Most, but not all maintain their records in one or more archival repositories. Within the A-Z Index, the Congregatio Pro Gentium Evangelizatione, the United States Catholic Conference, and dioceses and archdioceses are listed under “Catholic Church,” whereas local churches and missions and affiliated organizations are listed independently. The Catholic Church Holy See Three agencies of the Holy See include at least some documentation pertaining to Native Americans in the United States. They are the Archivio Vaticana or Archivum Secretum Vaticanum (Vatican Archives), which is in Vatican City, and the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vatican Library) and the Congregatio Pro Gentium Evangelizatione (Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples), both of which are in Rome. The Congregatio Pro Gentium Evangelizatione was formerly known as the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide or Propaganda Fide. United States Catholic Conference The Committee on Native American Catholics of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops monitors diocesan activities on Native American Catholics. The conference's website includes links to diocesan websites throughout the United States and includes the page Native American Catholics under its Department of Education. 1 Dioceses and Archdioceses The following dioceses and archdioceses hold Catholic records about Native Americans in the United States and are so-noted in entries and the Master Index. The dioceses are identified by contemporary names, which are arranged geographically by state and there under by lineage. -

THE PASSIONIST NUNS BECOME a “CONGREGATION” - Fr

THE PASSIONIST NUNS BECOME A “CONGREGATION” - Fr. Floriano De Fabiis (MAPRAES) 1. On 29 June 2018, the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life erected the “Congregation of the Nuns of the Passion of Jesus Christ”. The Decree of erection bears the signatures of João Braz Cardinal Aviz, Prefect, and Archbishop José Rodríguez Carballo, OFM, Secretary. With this decision of the Church, the monasteries of the Passionist Nuns leave the insulation of the “juridical” category, and enter into full communion as a new Congregation. It "enjoys public juridical personality under universal law".1 The change is extremely important and represents a "historic" step for the Passionist contemplative Institute. The new structure aims to and is committed to building the future of contemplative Passionist life within the context of the history of humanity. It does not change the nature of the contemplative Passionist life; in fact, it is established by the Church "to promote growth and life of the sui iuris Monasteries".2 a) The new juridical reality The Congregation of the Passionist Nuns is "composed of all monasteries sui iuris that profess the Rule and the Constitutions of the Founder, Saint Paul of the Cross," updated and approved by the Holy See on 28 April 1979. With the Decree of erection, the Vatican dicastery also approved the Statutes of the new monastic congregation. Therefore, from the date of the Decree, all autonomous monasteries of the Institute of the Religious of the Passion of Jesus Christ (structures, properties and religious) are part of this monastic Congregation. The basic instruments of the Congregation are the General Chapter, and the President and her Council. -

Consecrated Life April 19, 2018

14 15 THE CATHOLIC LIGHT • LIGHT THE CATHOLIC APRIL 19, 2018 APRIL 19, Images shown above: Mercy Hospital in Scranton, established by Sisters of Mercy. | Pilgrims are blessed at the annual Novena to Saint Ann conducted by the Passionists of Saint Paul of the Cross Province. | Student volunteers assist food distribution by Friends of the Poor, a ministry founded by Sister Adrian Barrett, I.H.M. (far left) | Sister Ellen Fischer, S.C.C. and students at a First Communion Retreat at Saint Jude, Mountain Top. partnered with the Diocese to staff Little Flower Italy responded to the personal invitation by Faith Facts: APRIL 19, 2018 • THE CATHOLIC LIGHT THE CATHOLIC 2018 • APRIL 19, Manor, a nursing home in Wilkes-Barre that Bishop Thomas C. O’Reilly to minister to the received its first residents in 1975. The facility growing number of Italian immigrants within the expanded with Saint Therese Residence, an Diocese of Scranton — specifically in the Greater Q Father Matthew Jankola, a Women and Men Religious Slovak priest of the Diocese, on-campus personal care facility that opened in Pittston area. The Oblate Fathers were assigned to founded the Sisters of Saints Serve Church in Many Capacities 1998. In 2011, the Diocese acquired the former several parishes and quickly associated themselves Cyril and Methodius, approved Consecrated Life Heritage House nursing home in Wilkes-Barre and with the poor and struggling immigrants as they by the Holy See in 1909. renamed it Saint Luke’s Villa. The Carmelite Sisters integrated themselves into the American way Women and men religious from numerous orders Mercy Hospital in Scranton. -

The Passionists of Holy Cross Province 660 Busse Highway, Park Ridge, IL 60068 Tel 847 518 8844 Web Passionist.Org

The Passionists of Holy Cross Province 660 Busse Highway, Park Ridge, IL 60068 tel 847 518 8844 web passionist.org … A Glossary / the Vocabulary / the Culture… October 6, 2019 Edition…a “work in progress”… Integrating Community & Collaboration & Formation & Practicalities … edits, additions welcome…contact [email protected] … … thanks to all who have provided input … … for updated copies, contact [email protected] … The Association of Local Superiors. A Province organization for local community ALS leaders/superiors, meeting as a group at least once each year, providing mutual support and direction in the ministry of local community leadership. A collection of requirements and policies for those pursuing a possible vocation to vowed Passionist life. Last reviewed and approved by Provincial leadership in Admission Policies November 2015, these policies address a variety of physical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual dimensions of an applicant’s life. A person in leadership at a retreat center, parish, or local community who is primarily Administrator responsible for the day-to-day operations of the facility and its people. An appointed team of vowed Passionists who consider the application of a man Admissions Board seeking entrance into vowed Passionist life. A man who is/was involved in any level of initial formation in Passionist vowed life; Alumni e.g. high school, college, novitiate, graduate/theology, professed brotherhood / priesthood. The official, organized “collection” of documents and items of historical significance to Archives Passionist life; Holy Cross Province archives are located at its Park Ridge IL Office, located in a professionally designed and maintained archive room. The labors, the “work” done for the mission of the Church, by lay, religious and priests. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Development And

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Development and Significance of the Religious Habit of Men A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Peter F. Killeen Washington, D.C. 2015 The Development and Significance of the Religious Habit of Men Peter F. Killeen, Ph.D. Director: Raymond Studzinski, Ph.D. In light of the diminished status of the religious habit since Vatican II, this dissertation explores the development and significance of the religious habit of male institutes of the Western Church. Currently (2015), many older religious believe that consecrated life may be lived more faithfully without a religious habit, while a high percentage of younger religious desire to wear a habit as a visual expression of their consecration. This difference of opinion is a cause of tension within many religious institutes. Despite tremendous change in the use of the religious habit since Vatican II, the habit has received minimal scholarly attention, and practically none written in English. This dissertation engages the initial legislative texts of numerous religious institutes in an effort to present the historical development of the habit of male religious of the Western Church. It also gives magisterial directives on the habit that have been issued throughout the history of the Church. The dissertation summarizes theological themes that have traditionally been connected to the religious habit, and it engages theological interpretations that have emerged since Vatican II which have contributed to the diminishment of the religious habit. -

From the Foot of the Cross

FFromrom thethe FFootoot ofof thethe CCrossross The Passionist Nuns of Saint Joseph Monastery in the Diocese of Owensboro KY Summer 2010 TTHEHE PPASSIONISTASSIONIST NNUNSUNS ININ NNORTHORTH AAMERICAMERICA 1910 - 2010 “The Five Flowers of Tarquinia” O n April 27, 1910, five weary and sea sick hours and endure lengthy interrogation in order to be cleared Passionist Nuns began a new chapter in our history as at customs and immigration control. they set foot in the United States of America. It was the vigil of the feast of St. Paul of the Cross, our holy These sufferings, and many others known only to their founder. Their mission was to found the first monastery Divine Spouse, were immediately rewarded by God’s gift of of Passionist Nuns in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. These new vocations. Three American postulants entered in July heroic Nuns (pictured above) would never again visit 1910 and a year later ten more young women came. The the monastery from which they came, the monastery Nuns were able to begin receiving guests in a separate founded by St. Paul of the Cross himself in what is now retreat house by July 1911. Tarquinia, Italy. Sacrificing even their own native land In 1926, the community was able to begin making new was just another part of their total gift of self to the foundations. Over the next century, eight other monasteries Crucified One to whom they belonged. of Passionists Nuns branched forth from the tree of the cross Known as the “Five Flowers of Tarquinia,” these planted by the founding group in Pittsburgh: Scranton, PA, “Spouses of the Crucified” excelled in natural and (now Clarks Summit), Owensboro (now Whitesville) KY, supernatural gifts.