A Passionist Friendship: Barnabas Ahern and Thomas Merton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life of Saint Paul of the Cross Founder of the Congregation of the Cross and Passion

The Life of Saint Paul of the Cross Founder of the Congregation of the Cross and Passion 1694-1775 Volume 1 – 1694-1741 Father Louis Therese of Jesus Agonizing, C.P. 1873 Fr. Simon Woods, C.P. (Translated from the third French Edition) 1959 (INDEX TO VOLUME ONE ON FINAL PAGES) DEDICATION to HIS EMINENCE FERDINAND CARDINAL DONNET Archbishop of Bordeaux Your Eminence, The Life of Saint Paul of the Cross, which it is my privilege to dedicate to you, may rightfully be called your very own. Without your Eminence the work may not have been completed, and I may never have realized the idea that I had in mind for a very long time. It is then the humble fruit of a tree planted by your own hands in the vineyard confided to your care by the Heavenly Father. It was when your Eminence was in Rome for the Beatification of our holy Founder that you obtained from His Holiness Pope Pius IX the sons of Saint Paul of the Cross for your Archdiocese… And, if this little family was welcome and took its humble beginnings in the fruitful soil of France under your protection and guidance, is it not due to your paternal interest and initiative? Soon, it is true, a learned and zealous clergy imitated your zeal; but in those days of supreme struggle, of unceasing conflict against the rights of the Church, your Eminence realized that it is necessary that zeal be united with learning, especially when the war “against the Lord and his Christ” becomes so universal. -

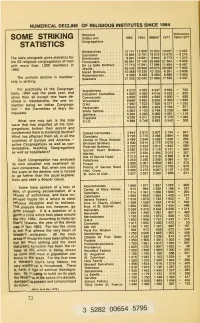

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Desert Encounters

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU Saint John’s Abbey Publications Saint John’s Abbey Summer 2012 Desert Encounters Aaron Raverty OSB College of Saint Benedict/Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/saint_johns_abbey_pubs Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Raverty, Aaron, OSB. “Desert Encounters.” Special issue theme: Meeting the Other. Desert Call, Contemplative Christianity and Vital Culture 12, no. 2 (Summer 2012):18–19. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Saint John’s Abbey Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. aint Benedict had nothing against hermits. As the oft-proclaimed Father of Western Mo- nasticism (480–547 CE), he reserved his highest praise for the cenobites—those monks Swho lived in community under a rule and an abbot. But he began his own ministry as a hermit monk, only later amassing a following of confreres. Listen to what Benedict says in his rule in chapter 1, “The Kinds of Monks”: [T]here are the anchorites or hermits, who have come through the test of living in a monastery for a long time, and have passed beyond the fi rst fervor of monastic life. Thanks to the help and guidance of many, they are now trained to fi ght against the devil. They have built up their strength and go from the battle line in the ranks of their brothers to the single combat of the desert. -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

“Beautiful Solitude Yet Within Easy Access of the City”

Volume 14 Issue 2 Spring 2007 The Passionists in Kingsbridge and Riverdale, Bronx, New York Neighborhood and Architecture: Cardinal Spellman Retreat House 1967 to 2007 This issue of the Passionist Heritage Newsletter celebrates Passionist history in the Bronx from 1904 to 1967. The first article revolves around conflicting definitions of Passionist preaching, prayer, and solitude; their buying and selling of choice real estate in the Bronx; and the participation of Passionists in local Riverdale neighborhood planning. The other articles recall the first person memories of Father Columkille Regan, C.P. and Brother Conrad Federspiel, C.P. as Cardinal Spellman Retreat House was being constructed and before it was dedicated in 1967. Combined, their insights offer readers a new historical perspective on the immediate and long-lasting influence of architect Brother Cajetan Baumann, O.F.M. on retreat ministry, maintenance, and budget operations. —Editor “Beautiful Solitude Yet Within Easy More on the Kingsbridge location can be found in the New York Times. On December 11, 1920, it was Access of the City” reported the Passionists purchased about four acres of land for $100,000. This included the “Eames house on By Father Rob Carbonneau C.P. the Claflin estate.” A July 25, 1923, article told how the exempt status of the Passionists and other organizations At first glance, people are quite amazed by the bucolic were being investigated in a city-wide sinking fund and spiritual beauty of the modern Cardinal Spellman project used to insure redemption of debt. On August 7, Retreat House operated by the Passionists at 5801 1924, a caption read: “Passionist Fathers Acquire Large Palisade Avenue in the Bronx, New York. -

CCD Signatories Listed by State

Catholic Climate Declaration Signatories Listed by State 806 as of November 13, 2019 Alabama ........................................................ 2 North Carolina............................................ 22 Alaska ........................................................... 2 Ohio ........................................................... 22 Arizona ......................................................... 2 Oklahoma ................................................... 24 Arkansas ....................................................... 2 Oregon ....................................................... 25 California ...................................................... 2 Pennsylvania............................................... 25 Colorado ....................................................... 4 Puerto Rico................................................. 27 District of Columbia ..................................... 5 Rhode Island .............................................. 27 Florida ..........................................................6 South Carolina ........................................... 27 Georgia .........................................................6 South Dakota ............................................. 27 Illinois .......................................................... 7 Tennessee ................................................... 28 Indiana .........................................................8 Texas .......................................................... 28 Iowa ..............................................................9 -

Remembering with Gratitude

The Passionist Nuns of Saint Joseph Monastery in the Diocese of Owensboro KY Lent 2020 ear Family & Friends, D Greetings and Blessed Lent to each and all of you! It is always our joy to come to you with the latest news at the monastery. This year, we begin celebrations of an awesome convergence of four Passionist an- niversaries beginning with the Tricentennial celebration in November of the inspiration of our Passionist charism — see page 6 for details. It is a time to dig back to the roots of our Congregation and to give thanks for the witness of those who have faithfully lived and passed on the flame of our Passionist life and charism. May we, too, faithfully im- part that flame! Please pray for our new members, and for more vocations who will carry the flame to the next generation. Our Sr. Lucia Marie just renewed her temporary vows; God- willing, 2020 will also see the vow renewals of her two juniorate companions. Sr. Miri- am Esther received the Holy Habit and her new name on our Founder’s feast, October 20, 2019, and two young ladies continue in our aspirancy program. God is at work! Witnessing and surrendering to God’s plan for our community is ever awesome and exciting….and also ever a lesson in trust! On page 7 you will see that we have embarked on a construction/renovation pro- ject and are putting on a new roof! His provi- dence ever watches over us with the help of YOUR spiritual and material support. Please consider helping us financially as we contin- ue to hold you in our daily grateful prayers, here at the Foot of the Cross! Gratefully in Christ our Redeemer, Mother John Mary and the Monastic Community Remembering With Gratitude.. -

Master List of Catholic Groups

Help Pages to Native Catholic Record Guides See User Guide for help on interpreting entries MASTER LIST OF CATHOLIC GROUPS new2003; rev2006-2017 These Catholic Church agencies and affiliated Catholic organizations have had past involvement in evangelization and ministry to Native Americans in the United States. Most, but not all maintain their records in one or more archival repositories. Within the A-Z Index, the Congregatio Pro Gentium Evangelizatione, the United States Catholic Conference, and dioceses and archdioceses are listed under “Catholic Church,” whereas local churches and missions and affiliated organizations are listed independently. The Catholic Church Holy See Three agencies of the Holy See include at least some documentation pertaining to Native Americans in the United States. They are the Archivio Vaticana or Archivum Secretum Vaticanum (Vatican Archives), which is in Vatican City, and the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (Vatican Library) and the Congregatio Pro Gentium Evangelizatione (Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples), both of which are in Rome. The Congregatio Pro Gentium Evangelizatione was formerly known as the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide or Propaganda Fide. United States Catholic Conference The Committee on Native American Catholics of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops monitors diocesan activities on Native American Catholics. The conference's website includes links to diocesan websites throughout the United States and includes the page Native American Catholics under its Department of Education. 1 Dioceses and Archdioceses The following dioceses and archdioceses hold Catholic records about Native Americans in the United States and are so-noted in entries and the Master Index. The dioceses are identified by contemporary names, which are arranged geographically by state and there under by lineage. -

THE PASSIONIST NUNS BECOME a “CONGREGATION” - Fr

THE PASSIONIST NUNS BECOME A “CONGREGATION” - Fr. Floriano De Fabiis (MAPRAES) 1. On 29 June 2018, the Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life erected the “Congregation of the Nuns of the Passion of Jesus Christ”. The Decree of erection bears the signatures of João Braz Cardinal Aviz, Prefect, and Archbishop José Rodríguez Carballo, OFM, Secretary. With this decision of the Church, the monasteries of the Passionist Nuns leave the insulation of the “juridical” category, and enter into full communion as a new Congregation. It "enjoys public juridical personality under universal law".1 The change is extremely important and represents a "historic" step for the Passionist contemplative Institute. The new structure aims to and is committed to building the future of contemplative Passionist life within the context of the history of humanity. It does not change the nature of the contemplative Passionist life; in fact, it is established by the Church "to promote growth and life of the sui iuris Monasteries".2 a) The new juridical reality The Congregation of the Passionist Nuns is "composed of all monasteries sui iuris that profess the Rule and the Constitutions of the Founder, Saint Paul of the Cross," updated and approved by the Holy See on 28 April 1979. With the Decree of erection, the Vatican dicastery also approved the Statutes of the new monastic congregation. Therefore, from the date of the Decree, all autonomous monasteries of the Institute of the Religious of the Passion of Jesus Christ (structures, properties and religious) are part of this monastic Congregation. The basic instruments of the Congregation are the General Chapter, and the President and her Council. -

Franciscan Convent to Be Dedicated Oct. 27

Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations FRANCISCAN CONVENT TO BE DEDICATED OCT. 27 Archbishop Vehr Declares at Dinner I Contents Copyrighted by the Catholic Press Society, Inc., 1943— Permission to Reprodnce, Except | Following Installation in Santa Fe on /urticles Otherwise Marked, Given After 12 M. Friday Following Issne War Cauiies Changes Founding of Diocoses Proves 14 Rapid Growth of C hurch in U. S. DENVER CATUaiC On Old Oakes Home Speaking at the dinner follow various agencies through which expressed amazement at the diffi To Progress Slowly ing the installation Sept. 23 of Oie the cause of religion— under the cult conditions under which some Most Rev. Edwin V. Byrne as specific guidance of the Hier of the priests live and praised the eighth Archbishop of Santa Fe, archy— is furthered, and the Cath clergy and people of New Mexico Tentative Date Announced by Archbishop Urban Archbishop Urban J, Vehr of Den olic press, which has had an almost in the highest terms for their sac REGISTER ver declared that the establish unbelievable growth. rifices on behalf of religion. The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We ment of six new archdioceses and Archbishop Vehr also paid spe Many Indiana Still Pagans Have Also the International News Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller J. Vehr; Some Improvements Must nine dioceses within a seven-year cial tribute to the Catholic Church Many Indians in the Southwest Services, Photo Features, and Wioe World Photos. period is indicative of the rapid Extension society, the Society for are stUl pagans, revealed Bishop Await Coming of Peace progress made by the Church in the Propag^ation of the Faith, the Espelage, former Chancellor of VOL. -

The Development of Catholic Institutions in Chicago During the Incumbencies of Bishop Quarter and Bishop Van De Velde, 1844-1853

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1935 The Development of Catholic Institutions in Chicago During the Incumbencies of Bishop Quarter and Bishop Van De Velde, 1844-1853 Marie Catherine Tangney Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Tangney, Marie Catherine, "The Development of Catholic Institutions in Chicago During the Incumbencies of Bishop Quarter and Bishop Van De Velde, 1844-1853" (1935). Master's Theses. 391. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/391 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1935 Marie Catherine Tangney THE DEVELOPMENT OF CATHOLIC INSTITUTIONS IN CHICAGO DURING THE INCUMBENCIES OF BISHOP QUARTER AND BISHOP VAN DE VELDE 1844-1855 By MARIE CATHERINE TANGNEY A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University, 1955 PREFACE The Catholic Diocese of Chicago can be proud of its numerous institutions especially those in Chicago and the Seminary at Mundelein, Illinois. But probably few people realize when, where, and b,y whom the nucleus of these institutions was started. When Bishop Quarter arrived in Chicago in 1844, there was one Catholic Church and two Catholic Priests. With this background, he began to build. -

Consecrated Life April 19, 2018

14 15 THE CATHOLIC LIGHT • LIGHT THE CATHOLIC APRIL 19, 2018 APRIL 19, Images shown above: Mercy Hospital in Scranton, established by Sisters of Mercy. | Pilgrims are blessed at the annual Novena to Saint Ann conducted by the Passionists of Saint Paul of the Cross Province. | Student volunteers assist food distribution by Friends of the Poor, a ministry founded by Sister Adrian Barrett, I.H.M. (far left) | Sister Ellen Fischer, S.C.C. and students at a First Communion Retreat at Saint Jude, Mountain Top. partnered with the Diocese to staff Little Flower Italy responded to the personal invitation by Faith Facts: APRIL 19, 2018 • THE CATHOLIC LIGHT THE CATHOLIC 2018 • APRIL 19, Manor, a nursing home in Wilkes-Barre that Bishop Thomas C. O’Reilly to minister to the received its first residents in 1975. The facility growing number of Italian immigrants within the expanded with Saint Therese Residence, an Diocese of Scranton — specifically in the Greater Q Father Matthew Jankola, a Women and Men Religious Slovak priest of the Diocese, on-campus personal care facility that opened in Pittston area. The Oblate Fathers were assigned to founded the Sisters of Saints Serve Church in Many Capacities 1998. In 2011, the Diocese acquired the former several parishes and quickly associated themselves Cyril and Methodius, approved Consecrated Life Heritage House nursing home in Wilkes-Barre and with the poor and struggling immigrants as they by the Holy See in 1909. renamed it Saint Luke’s Villa. The Carmelite Sisters integrated themselves into the American way Women and men religious from numerous orders Mercy Hospital in Scranton.