IPO and Earnings Management on Post

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Security Master Symbol Description a AGILENT TECHNOLOGIES INC AA

*The information contained herein is believed to Security Master be reliable but is neither guaranteed by EQIS Capital Management, Inc. its principles nor any affiliated EQIS companies. This information is Symbol Description intended for the exclusive use of investment Adviser Representative. This list is subject to A AGILENT TECHNOLOGIES INC change. AA ALCOA CORP COM Advisor Services are offered through EQIS AAAAX DEUTSCHE ALTERNATIVE ASSET ALLOCATION FU Capital Management, Inc. an SEC Registered AAAP ADVANCED ACCELERATOR APPLIC SPONSORED AD Investment Adviser. For information purposes AAASX DEUTSCHE ALTERNATIVE ASSET ALLOCATION F only, not for public distribution. AABPX AMERICAN BEACON BALANCED INVESTOR AAC AAC HLDGS INC COM AACFX AIM CHINA A AADAX AIM GROWTH ALLOCATION CLASS A AADEX AMERICAN BEACON LARGE CAP VALUE INSTL AADR ADVISORSHARES WCM/BNY MLNFCSD GR ADR ETF AAGIY AIA GROUP LTD SPONS ADR AAGPX AMERICAN BEACON LARGE CAP VALUE INVESTOR AAIFX CROW POINT ALTERNATIVE INCOME FUND AAIPX AMERICAN BEACON INTERNATIONAL EQUITY INV AAL AMERICAN AIRLS GROUP INC COM AAMC ALTISOURCE ASSET MGMT CORP COM AAME ATLANTIC AMERN CORP AAN AARONS, INC. CL A AAOI APPLIED OPTOELECTRONICS INC COM AAON AAON INC PAR $0.004 AAP ADVANCED AUTO PARTS INC AAPC ATLANTIC ALLIANCE PARTNER CORP SHS AAPL APPLE INC COM AAT AMERICAN ASSETS TR INC COM AAU ALMADEN MINERALS LTD AAV ADVANTAGE OIL & GAS LTD AAWW ATLAS AIR WORLDWIDE HLDGS INC COM NEW AAXJ ISHARES MSCI ALL COUNTRY ASIA EX JAPAN I AB ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN HOLDING LP UNIT LTD PA ABAC AOXIN TIANLI GROUP INC NEW -

Maximum Internet Security: a Hackers Guide - Networking - Intrusion Detection

- Maximum Internet Security: A Hackers Guide - Networking - Intrusion Detection Exact Phrase All Words Search Tips Maximum Internet Security: A Hackers Guide Author: Publishing Sams Web Price: $49.99 US Publisher: Sams Featured Author ISBN: 1575212684 Benoît Marchal Publication Date: 6/25/97 Pages: 928 Benoît Marchal Table of Contents runs Pineapplesoft, a Save to MyInformIT consulting company that specializes in Internet applications — Now more than ever, it is imperative that users be able to protect their system particularly e-commerce, from hackers trashing their Web sites or stealing information. Written by a XML, and Java. In 1997, reformed hacker, this comprehensive resource identifies security holes in Ben co-founded the common computer and network systems, allowing system administrators to XML/EDI Group, a think discover faults inherent within their network- and work toward a solution to tank that promotes the use those problems. of XML in e-commerce applications. Table of Contents I Setting the Stage 1 -Why Did I Write This Book? 2 -How This Book Will Help You Featured Book 3 -Hackers and Crackers Sams Teach 4 -Just Who Can Be Hacked, Anyway? Yourself Shell II Understanding the Terrain Programming in 5 -Is Security a Futile Endeavor? 24 Hours 6 -A Brief Primer on TCP/IP 7 -Birth of a Network: The Internet Take control of your 8 -Internet Warfare systems by harnessing the power of the shell. III Tools 9 -Scanners 10 -Password Crackers 11 -Trojans 12 -Sniffers 13 -Techniques to Hide One's Identity 14 -Destructive Devices IV Platforms -

List of Marginable OTC Stocks

List of Marginable OTC Stocks @ENTERTAINMENT, INC. ABACAN RESOURCE CORPORATION ACE CASH EXPRESS, INC. $.01 par common No par common $.01 par common 1ST BANCORP (Indiana) ABACUS DIRECT CORPORATION ACE*COMM CORPORATION $1.00 par common $.001 par common $.01 par common 1ST BERGEN BANCORP ABAXIS, INC. ACETO CORPORATION No par common No par common $.01 par common 1ST SOURCE CORPORATION ABC BANCORP (Georgia) ACMAT CORPORATION $1.00 par common $1.00 par common Class A, no par common Fixed rate cumulative trust preferred securities of 1st Source Capital ABC DISPENSING TECHNOLOGIES, INC. ACORN PRODUCTS, INC. Floating rate cumulative trust preferred $.01 par common $.001 par common securities of 1st Source ABC RAIL PRODUCTS CORPORATION ACRES GAMING INCORPORATED 3-D GEOPHYSICAL, INC. $.01 par common $.01 par common $.01 par common ABER RESOURCES LTD. ACRODYNE COMMUNICATIONS, INC. 3-D SYSTEMS CORPORATION No par common $.01 par common $.001 par common ABIGAIL ADAMS NATIONAL BANCORP, INC. †ACSYS, INC. 3COM CORPORATION $.01 par common No par common No par common ABINGTON BANCORP, INC. (Massachusetts) ACT MANUFACTURING, INC. 3D LABS INC. LIMITED $.10 par common $.01 par common $.01 par common ABIOMED, INC. ACT NETWORKS, INC. 3DFX INTERACTIVE, INC. $.01 par common $.01 par common No par common ABLE TELCOM HOLDING CORPORATION ACT TELECONFERENCING, INC. 3DO COMPANY, THE $.001 par common No par common $.01 par common ABR INFORMATION SERVICES INC. ACTEL CORPORATION 3DX TECHNOLOGIES, INC. $.01 par common $.001 par common $.01 par common ABRAMS INDUSTRIES, INC. ACTION PERFORMANCE COMPANIES, INC. 4 KIDS ENTERTAINMENT, INC. $1.00 par common $.01 par common $.01 par common 4FRONT TECHNOLOGIES, INC. -

Tfs Capital Investment Trust

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-CSRS Certified semi-annual shareholder report of registered management investment companies filed on Form N-CSR Filing Date: 2012-07-02 | Period of Report: 2012-04-30 SEC Accession No. 0001398344-12-002141 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER TFS CAPITAL INVESTMENT TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 225 PICTORIA DRIVE, SUITE 1800 BAYBERRY COURT CIK:1283381| IRS No.: 200838619 | State of Incorp.:OH | Fiscal Year End: 1030 450 SUITE 103 Type: N-CSRS | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-21531 | Film No.: 12940753 CINCINNATI OH 45246 RICHMOND VA 23226 513-587-3400 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document OMB APPROVAL OMB Number: 3235-0570 Expires: January 31, 2014 Estimated average burden hours per response: 20.6 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-CSR CERTIFIED SHAREHOLDER REPORT OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANIES Investment Company Act file number 811-21531 TFS Capital Investment Trust (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1800 Bayberry Court, Suite 103 Richmond, Virginia 23226 Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Wade R. Bridge, Esq. Ultimus Fund Solutions, LLC 225 Pictoria Drive, Suite 450 Cincinnati, Ohio 45246 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (804) 484-1401 Date of fiscal year end: October 31, 2012 Date of reporting period: April 30, 2012 Form N-CSR is to be used by management investment companies to file reports with the Commission not later than 10 days after the transmission to stockholders of any report that is required to be transmitted to stockholders under Rule 30e-1 under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (17 CFR 270.30e-1). -

Chicago Board Options Exchange Annual Report 2001

01 Chicago Board Options Exchange Annual Report 2001 cv2 CBOE ‘01 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 CBOE is the largest and 01010101010101010most successful options 01010101010101010marketplace in the world. 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010 01010101010101010ifc1 CBOE ‘01 ONE HAS OPPORTUNITIES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange provides customers with a wide selection of products to achieve their unique investment goals. ONE HAS RESPONSIBILITIES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange is responsible for representing the interests of its members and customers. Whether testifying before Congress, commenting on proposed legislation or working with the Securities and Exchange Commission on finalizing regulations, the CBOE weighs in on behalf of options users everywhere. As an advocate for informed investing, CBOE offers a wide array of educational vehicles, all targeted at educating investors about the use of options as an effective risk management tool. ONE HAS RESOURCES The NUMBER ONE Options Exchange offers a wide variety of resources beginning with a large community of traders who are the most experienced, highly-skilled, well-capitalized liquidity providers in the options arena. In addition, CBOE has a unique, sophisticated hybrid trading floor that facilitates efficient trading. 01 CBOE ‘01 2 CBOE ‘01 “ TO BE THE LEADING MARKETPLACE FOR FINANCIAL DERIVATIVE PRODUCTS, WITH FAIR AND EFFICIENT MARKETS CHARACTERIZED BY DEPTH, LIQUIDITY AND BEST EXECUTION OF PARTICIPANT ORDERS.” CBOE MISSION LETTER FROM THE OFFICE OF THE CHAIRMAN Unprecedented challenges and a need for strategic agility characterized a positive but demanding year in the overall options marketplace. The Chicago Board Options Exchange ® (CBOE®) enjoyed a record-breaking fiscal year, with a 2.2% growth in contracts traded when compared to Fiscal Year 2000, also a record-breaker. -

2015 Valuation Handbook – Guide to Cost of Capital and Data Published Therein in Connection with Their Internal Business Operations

Market Results Through #DBDLADQ 2014 201 Valuation Handbook Guide to Cost of Capital Industry Risk Premia Company List Cover image: Duff & Phelps Cover design: Tim Harms Copyright © 2015 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748- 6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. The forgoing does not preclude End-users from using the 2015 Valuation Handbook – Guide to Cost of Capital and data published therein in connection with their internal business operations. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 and KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As of Date : 12/31/2013 Accounting Status : REVISED

Asset Detail Acct Base Currency Code : USD ALL KR2 AND KR3 - KR2GALLKRS00 As Of Date : 12/31/2013 Accounting Status : REVISED . Mellon Security ID Security Description Shares/Par Base Market Value Grand Total 36,179,254,463.894 15,610,214,163.19 ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS 15,450,499.520 15,450,499.52 MKP OPPORTUNITY OFFSHORE LTD 15,450,499.520 15,450,499.52 CASH & CASH EQUIVALENTS 877,174,023.720 877,959,915.42 BANC OF AM CORP REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 20,000,000.000 20,000,000.00 BANK OF AMERICA (BOA) 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 52,000.000 52,000.00 BARC CCP COLLATERAL VAR RT 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 28,000.000 28,000.00 BARCLAYS CASH COLLATERAL VAR RT 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 543,000.000 543,000.00 BARCLAYS CP REPO REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 12,000,000.000 12,000,000.00 BARCLAYS CP REPO REPO 0.040% 01/17/2014 DD 12/18/13 9,200,000.000 9,200,000.00 BNY MELLON CASH RESERVE 0.010% 12/31/2049 DD 06/26/97 1,184,749.080 1,184,749.08 CANTOR REPO A REPO 0.170% 01/02/2014 DD 12/19/13 67,000,000.000 67,000,000.00 CASH COLLATERAL HELD AT CITIGROUP 387,000.000 387,000.00 CASH HELD AS COLLATERAL AT DEUTSCHE 169,000.000 169,000.00 CITIGROUP CAT 2MM REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 8,300,000.000 8,300,000.00 CME CCP COLL HELD AT GSC 100,000.000 100,000.00 CREDIT SUISSE REPO 0.010% 01/02/2014 DD 12/31/13 16,300,000.000 16,300,000.00 CSFB CCP COLLATERAL 0.010% 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 1,553,000.000 1,553,000.00 DEUTSCHE BANK VAR RT 01/01/2049 DD 07/01/08 668,000.000 668,000.00 DEUTSCHE BK TD 0.180% 01/02/2014 DD 12/18/13 270,000,000.000 270,000,000.00 -

6709BWOL Webstock

RIDING THE WEB-STOCK ROLLER COASTER Reprinted from the August 12, 2004 issue of BusinessWeek Online. Copyright © 2004 by The McGraw-Hill Companies. This reprint implies no endorsement, either tacit or expressed, of any company, product, service or investment opportunity. RIDING THE WEB-STOCK ROLLER COASTER Our BW Web 20 Index tracks a selection of favorite Net stocks, and this column will help interpret the ups and downs he past month has been rotten Just last week, Forrester Research christening the BW Web 20 Index Tfor Internet investors. Stocks raised its e-commerce forecast, pre- – is intended to help aggressive have been hammered since second- dicting U.S. online sales of $227 bil- investors accept the risk inherent in quarter earnings showed Web out- lion in 2007, up from earlier projec- the Web, but balance it by focusing fits growing pretty much as they had tions of $204 billion. Forrester on “real” companies with solid prod- promised – a change from their habit expects e-commerce in the U.S. to ucts, services, and profits. Every of slightly besting quarterly projec- grow 14% annually through 2010 – month, this column will do more than tions. The carnage has been just as three to four times faster than the track how stocks in our index trade – severe in the Real World Internet economy. Meanwhile, growth in it also will help investors figure out Index, a group of Web stocks we Europe is predicted to average 33% which rallies are sustainable and spot picked in 2002 to help ordinary annually through 2009. the bubblicious behavior that earned investors play the Internet without Net investing a bad rap. -

List of Section 13F Securities

List of Section 13F Securities First Quarter FY 2016 Copyright (c) 2016 American Bankers Association. CUSIP Numbers and descriptions are used with permission by Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau, a division of The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. No redistribution without permission from Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau. Standard & Poors CUSIP Service Bureau does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the CUSIP Numbers and standard descriptions included herein and neither the American Bankers Association nor Standard & Poor's CUSIP Service Bureau shall be responsible for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of the use of such information. U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission OFFICIAL LIST OF SECTION 13(f) SECURITIES USER INFORMATION SHEET General This list of “Section 13(f) securities” as defined by Rule 13f-1(c) [17 CFR 240.13f-1(c)] is made available to the public pursuant to Section13 (f) (3) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 [15 USC 78m(f) (3)]. It is made available for use in the preparation of reports filed with the Securities and Exhange Commission pursuant to Rule 13f-1 [17 CFR 240.13f-1] under Section 13(f) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. An updated list is published on a quarterly basis. This list is current as of March 15, 2016, and may be relied on by institutional investment managers filing Form 13F reports for the calendar quarter ending March 31, 2016. Institutional investment managers should report holdings--number of shares and fair market value--as of the last day of the calendar quarter as required by [ Section 13(f)(1) and Rule 13f-1] thereunder. -

Software Industry Financial Report Contents

The Software Industry Financial Report SOFTWARE INDUSTRY FINANCIAL REPORT CONTENTS About Software Equity Group Leaders in Software M&A 4 Extensive Global Reach 5 Software Industry Macroeconomics Global GDP 8 U.S. GDP and Unemployment 9 Global IT Spending 10 E-Commerce and Digital Advertising Spend 11 SEG Indices vs. Benchmark Indices 12 Public Software Financial and Valuation Performance The SEG Software Index 14 The SEG Software Index: Financial Performance 15-17 The SEG Software Index: Market Multiples 18-19 The SEG Software Index by Product Category 20 The SEG Software Index by Product Category: Financial Performance 21 The SEG Software Index by Product Category: Market Multiples 22 Public SaaS Company Financial and Valuation Performance The SEG SaaS Index 24 The SEG SaaS Index Detail 25 The SEG SaaS Index: Financial Performance 26-28 The SEG SaaS Index: Market Multiples 29-30 The SEG SaaS Index by Product Category 31 The SEG SaaS Index by Product Category: Financial Performance 32 The SEG SaaS Index by Product Category: Market Multiples 33 Public Internet Company Financial and Valuation Performance The SEG Internet Index 35 The SEG Internet Index: Financial Performance 36-38 The SEG Internet Index: Market Multiples 39-40 The SEG Internet Index by Product Category 41 The SEG Internet Index by Product Category: Financial Performance 42 The SEG Internet Index by Product Category: Market Multiples 43 1 Q3 2013 Software Industry Financial Report Copyright © 2013 by Software Equity Group, LLC All Rights Reserved SOFTWARE INDUSTRY FINANCIAL -

Technology Fast 500

2001 Deloitte & Touche Technology Fast 500 www.fast500.com Leading the Way It’s been a tough year for the technology sector, and the com- Industry segments represented were relatively stable from panies on this year’s Deloitte & Touche Technology Fast 500 last year, with software companies again leading the way are not immune to the effects of the tech correction and the with 221 companies or 44 percent of the list. Notably, given slowing of the U.S. economy. Indeed, some Fast 500 compa- the malaise in the field, communications companies jumped nies have seen their businesses slow significantly in 2001 and from nine percent to 13 percent of the list.While Internet are struggling after five years of dramatic growth (the 2001 companies are prominent at the top of the list, as a group, Fast 500 measures five-year growth through fiscal 2000). they slid from 17 percent to 15 percent. With that said, this year’s Technology Fast 500 companies, as Geographical Shifts a group, found a way to grow even faster than their prede- After a one-year hiatus, the West resumed its position at the cessors.The 2001 Technology Fast 500 averaged a five-year head of the technology class, accounting for 32 percent of percentage revenue growth rate of 6,184 percent, compared the Fast 500, up from 27 percent. California was, by far, the to 3,956 percent for last year’s list.The top five companies biggest contributor to the list with 132 companies, including grew an average of 93,496 percent, compared to 59,367 percent two of the top three companies, calling the Golden State for last year’s top five. -

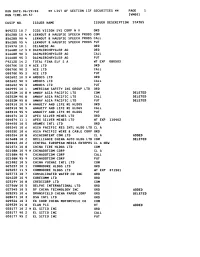

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11