Antisemitic Rumours and Violence in Corfu at the End of 19Th Century By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Corfu : the Tranformation of the Physiognomy of a Capital City to a Provisional One Through Testimonies from Literature Athanassios BALERMPAS

reviewed paper City of Corfu : The Tranformation of the Physiognomy of a Capital City To A Provisional One Through Testimonies From Literature Athanassios BALERMPAS National Technical University of Athens, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Athens, Greece, Email: [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION The historical line of a city has a significant impact in the formation of its physical and emotional physiognomy which the city projects. It plays a major part in the creation of the speech (logos) and myth (mythos) that determines each significant urban formation. Let us not forget that the speech and the myth establish the ideological foundations of a city. However, the historical context does not only influence the above two elements of its physiognomy; it also plays a central part in the formation of its society, and the architectural space is a significant factor in determining society formation, according to the theories of Rossi, Hiller and Hanson1 ; in turn both society and architecture are defined significantly by the historical and, consequently, social events. In addition, we should not forget that the inheritance of the historical events in a city determines the social, political and economic system that governs the city. His system, according to Joseph and Julia Stefanou2 , is the main factor for the physiognomy of the city, since it influences its form, style, size and development. Nobody can argue that one of Vienna’s most celebrated characteristics was the period in history when the city was the capital of the empire of the Hapsburgs. Similarly, all the other historical events that happened in the same space have also left their traces in the image of the city. -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 15, 2018 Family and Labour in Corfu Manufacturing, 1920–1944 Kopanas Dimitrios University of Ioannina https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.20447 Copyright © 2019 Dimitrios Kopanas To cite this article: Kopanas, D. (2019). Family and Labour in Corfu Manufacturing, 1920–1944. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 15, 133-162. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.20447 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 24/12/2020 04:49:42 | FAMILY AND LABOUR IN CORFU MANUFACTURING, 1920–1944 Dimitrios Kopanas Abstract: This article concentrates on the relation between labour and family in the secondary sector of production of Corfu. It argues that family was crucial in forming the main characteristics of the labour force. The familial division of labour according to gender and age is examined not only as a decisive determinant in the categorisation of work positions as skilled and unskilled but also as a factor that defined the temporality or permanence of labour. It also focuses on the role of local and family networks and their effect on the labour market. These questions, thoroughly discussed by labour historians, will be applied to the case of Corfu, in an effort to complete the Greek paradigm. Over the last 30 years, research has repeatedly questioned the significance of the sole male breadwinner family and started focusing on a workforce that had been neglected, namely female and juvenile family members. Their participation in raising family income, once downplayed, has become a key subject in understanding labour relations since the emergence of capitalism.1 Social and economic history have systematically discussed the role of the family not only as a primary provider of capital and labour to commercial firms and industries but also as an institution whose members are subordinate to the social relations within it. -

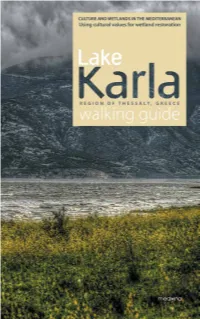

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research -

Historical Cycles of the Economy of Modern Greece from 1821 to the Present

GreeSE Papers Hellenic Observatory Discussion Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe Paper No. 158 Historical Cycles of the Economy of Modern Greece from 1821 to the Present George Alogoskoufis April 2021 Historical Cycles of the Economy of Modern Greece from 1821 to the Present George Alogoskoufis GreeSE Paper No. 158 Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe All views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Hellenic Observatory or the LSE © George Alogoskoufis Contents I. The Major Historical Cycles of Modern Greece II. Nation Building, the ‘Great Idea’ and Economic Instability and Stagnation, 1821- 1898 II.1 The Re-awakening of the Greek National Conscience and the War of Independence II.2 Kapodistrias and the Creation of the Greek State II.3 State Building under the Regency and the Monarchy II.4 The Economy under the Monarchy and the 1843 ‘Default’ II.5 The Constitution of 1844, the ‘Great Idea’ and the End of Absolute Monarchy II.6 Changing of the Guard, Political Reforms and Territorial Gains II.7 Fiscal and Monetary Instability, External Borrowing and the 1893 ‘Default’ II.8 Transformations and Fluctuations in a Stagnant Economy III. Wars, Internal Conflicts and National Expansion and Consolidation, 1899-1949 III.1 From Economic Stabilisation to the Balkan Triumphs III.2 The ‘National Schism’, the Asia Minor Disaster and the End of the ‘Great Idea’ III.3 Political Instability, Economic Stabilisation, ‘Default’ of 1932 and Rapid Recovery III.4 From the Disaster of the Occupation to the Catastrophic Civil War III.5 Growth and Recessions from the 19th Century to World War II IV. -

The Question of Northern Epirus at the Peace Conference

Publication No, 1. THE QUESTION OF NORTHERN EPIRUS AT THE PEACE CONFERENCE BY NICHOLAS J. CASSAVETES Honorary Secretary of the Pan-Epirotie Union of America BMTKB BY CAEEOLL N. BROWN, PH.D. *v PUBLISHED FOR THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA ? WâTBB STREET, BOSTOH, MASS. BY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMERICAN BRANCH 85 WEST 32ND S1REET, NEW YÛHK 1919 THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA GENERAL COUNCIL Honorary President George Christ Zographos ( Ex-president of the Autonomous State of Epirus and formes Minister of Foreign Affairs of Greece) Honorary Secretary Nicholas J. Cassavetes President Vassilios K. Meliones Vice-President Sophocles Hadjiyannis Treasurer George Geromtakis General Secretary Michael 0. Mihailidis Assistant Secretary Evangelos Despotes CENTRAL OFFICE, ? Water Street, Room 4Î0, BOSTON, MASS. THE QUESTION OF NORTHERN EPIRUS AT THE PEACE CONFERENCE BY NICHOLAS J. CASSAVETES Honorary Secretary of the Pan-Bpirotic Union of America EDITED BY CARROLL N. BROWN, PH.D. PUBLISHED FOR THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA 7 WATER STREET, BOSTON, MASS. BY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMERICAN BRANCH 85 WEST 82ND STREET, NEW YORK 1919 COPYIUQHT 1919 BY THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PKKSS AMERICAN BRANCH PREFACE Though the question of Northern Epirus is not pre eminent among the numerous questions which have arisen since the political waters of Europe were set into violent motion by the War, its importance can be measured neither by the numbers of the people involved, nor by the serious ness of the dangers that may arise from the disagreement of the two or three nations concerned in the dispute. Northern Epirus is the smallest of the disputed territories in Europe, and its population is not more than 300,000. -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 11, 2014 Index Hatzopoulos Marios https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 Copyright © 2014 To cite this article: Hatzopoulos, M. (2014). Index. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 11, I-XCII. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX, VOLUMES I-X Compiled by / Compilé par Marios Hatzopoulos http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX Aachen (Congress of) X/161 Académie des Inscriptions et Belles- Abadan IX/215-216 Lettres, Paris II/67, 71, 109; III/178; Abbott (family) VI/130, 132, 138-139, V/79; VI/54, 65, 71, 107; IX/174-176 141, 143, 146-147, 149 Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Abbott, Annetta VI/130, 142, 144-145, Belles-Lettres de Toulouse VI/54 147-150 Academy of France I/224; V/69, 79 Abbott, Bartolomew Edward VI/129- Acciajuoli (family) IX/29 132, 136-138, 140-157 Acciajuoli, Lapa IX/29 Abbott, Canella-Maria VI/130, 145, 147- Acciarello VII/271 150 Achaia I/266; X/306 Abbott, Caroline Sarah VI/149-150 Achilles I/64 Abbott, George Frederic (the elder) VI/130 Acropolis II/70; III/69; VIII/87 Abbott, George Frederic (the younger) Acton, John VII/110 VI/130, 136, 138-139, 141-150, 155 Adam (biblical person) IX/26 Abbott, George VI/130 Adams, -

Storia Militare Moderna

NUOVA RIVISTA INTERDISCIPLINARE DELLA SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI STORIA MILITARE Fascicolo 3. Giugno 2020 Storia militare moderna Società Italiana di Storia Militare Direttore scientifico Virgilio Ilari Vicedirettore scientifico Giovanni Brizzi Direttore responsabile Gregory Claude Alegi Redazione Viviana Castelli Consiglio Scientifico. Presidente: Massimo De Leonardis. Membri stranieri: Christopher Bassford, Floribert Baudet, Stathis Birthacas, Jeremy Martin Black, Loretana de Libero, Magdalena de Pazzis Pi Corrales, Gregory Hanlon, John Hattendorf, Yann Le Bohec, Aleksei Nikolaevič Lobin, Prof. Armando Marques Guedes, Prof. Dennis Showalter (†). Membri italiani: Livio Antonielli, Antonello Folco Biagini, Aldino Bondesan, Franco Cardini, Piero Cimbolli Spagnesi, Piero del Negro, Giuseppe De Vergottini, Carlo Galli, Roberta Ivaldi, Nicola Labanca, Luigi Loreto, Gian Enrico Rusconi, Carla Sodini, Donato Tamblé, Comitato consultivo sulle scienze militari e gli studi di strategia, intelligence e geopolitica: Lucio Caracciolo, Flavio Carbone, Basilio Di Martino, Antulio Joseph Echevarria II, Carlo Jean, Gianfranco Linzi, Edward N. Luttwak, Matteo Paesano, Ferdinando Sanfelice di Monteforte. Consulenti di aree scientifiche interdisciplinari: Donato Tamblé (Archival Sciences), Piero Cimbolli Spagnesi (Architecture and Engineering), Immacolata Eramo (Philology of Military Treatises), Simonetta Conti (Historical Geo-Cartography), Lucio Caracciolo (Geopolitics), Jeremy Martin Black (Global Military History), Elisabetta Fiocchi Malaspina (History of International -

Modern Greek

UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD FACULTY OF MEDIEVAL AND MODERN LANGUAGES Handbook for the Final Honour School in Modern Greek 2016-17 For students who start their FHS course in October 2016 and expect to be taking the FHS examination in Trinity Term 2019 FINAL HONOUR SCHOOL DESCRIPTION OF LANGUAGE PAPERS Paper I: Translation into Greek and Essay This paper consists of a prose translation from English into Greek of approximately 250 words and an essay in Greek of about 500-700 words. Classes for this paper will help you to actively use more complex syntactical structures, acquire a richer vocabulary, enhance your command of the written language, and enable you to write clearly and coherently on sophisticated topics. Paper IIA and IIB: Translation from Greek This paper consists of a translation from Greek into English of two texts of about 250 words each. Classes for this paper will help you expand your vocabulary and deepen your understanding of complex syntactical structures in Greek, as well as improve your translation techniques. Paper III: Translation from Katharaevousa ORAL EXAMINATION The Oral Examination consists of a Listening and an Oral Exercise. 1) For the Listening Comprehension, candidates listen twice to a spoken text of approximately 5 minutes in length. After the first reading, candidates are given questions in English relating to the material which must be answered also in English. 2) The Oral exam consists of two parts: a) Discourse in Greek Candidates are given an number of topics from which they must choose one to prepare a short presentation (5 minutes). Preparation time 15 minutes. -

Final Copy 2018 11 06 Zarok

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Zarokostas, Evangelos Title: From observatory to dominion geopolitics, colonial knowledge and the origins of the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands, 1797-1822 General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. From observatory to dominion: geopolitics, colonial knowledge and the origins of the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands, 1797-1822 Evangelos (Aggelis) Zarokostas A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of PhD, Historical Studies in the Faculty of the Arts, School of Humanities, June 2018 word count: 73,927 1 Abstract The thesis explores official information-gathering and colonial rule during the transition which led to the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands, between 1797 and 1822. -

Theotokis, Georgios (2010) the Campaigns of the Norman Dukes of Southern Italy Against Byzantium, in the Years Between 1071 and 1108 AD

Theotokis, Georgios (2010) The campaigns of the Norman dukes of southern Italy against Byzantium, in the years between 1071 and 1108 AD. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1884/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the Author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The topic of my thesis is “The campaigns of the Norman dukes of southern Italy to Byzantium, in the years between 1071 and 1108 A.D.” As the title suggests, I am examining all the main campaigns conducted by the Normans against Byzantine provinces, in the period from the fall of Bari, the Byzantine capital of Apulia and the seat of the Byzantine governor (catepano) of Italy in 1071, to the Treaty of Devol that marked the end of Bohemond of Taranto’s Illyrian campaign in 1108. My thesis, however, aims to focus specifically on the military aspects of these confrontations, an area which for this period has been surprisingly neglected in the existing secondary literature. My intention is to give answers to a series of questions, of which -

The Ionian Islands in the Napoleonic Empire: the Period of Donzelot 1808-1814, by Thomas Zacharis 1 More Furniture 10 Spain Triumphant: the Texas Campaign of 1813 14

THE NAPOLEONIC HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER December Supplement 2013 The Ionian Islands in the Napoleonic Empire: the Period of Donzelot 1808-1814, by Thomas Zacharis 1 More Furniture 10 Spain Triumphant: The Texas Campaign of 1813 14 A Supplement? We looked forward to publishing this article by our friend, Thomas Zacharis, in Thessaloniki, but we thought it might be too long for anewsletter. The newsletters are limited by the file size. Too large a file can be awkward to send. But it gave us an excuse for a supplement, and that gives us an opportunity to add a few items for which there wasn't room in the November-December Newsletter. There’s not much in the way of pictures of Donzelot. This one was done by André Dutertre, one of the savants who joined Napoleon for the Egyptian Antidote for the winter blues? campaign, and drew 184 portraits of the soldiers and scientists he met. February 1st. Fortunately, one of them was Donzelot. The NHS will have a special THE IONIAN ISLANDS IN THE NAPOLEONIC one day conference in Louis- ville, KY. We’ll all go see EMPIRE: THE PERIOD OF DONZELOT (1808-1814) the Eye of Napoleon exhibi- by Thomas Zacharis tion, and much more. Keep The first Chief of Staff of the right 7 January 1764 and died at the castle checking napoleonichistori- wing of the Army of the Rhine, of Ville-Évrard (Neuilly sur Marne, calsociety.com for updates. Comte François-Xavier Donzelot Seine-St.-Denis) on 11th June 1843. was born in Mamirolle (Doubs) on He managed first to bring himself December 2013 Supplement Page 1 THE NAPOLEONIC HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER to the attention of General Moreau, bridgehead at Vouthroto (Boudino). -

John C Apodi St Ria S and the Greek Historians: a Selective Bibliographical Review

JOHN C APODI ST RIA S AND THE GREEK HISTORIANS: A SELECTIVE BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REVIEW Count John Capodistrias remains one of the most controversial political figures of the first three decades of the lj)th century. His career began in his native country, the Ionian Islands, in 1800, as A member of the Government under the Russians. In 1807, when the Islands were ceded to the French, Capodistrias remained loyal to RussiA and left for St Petersburg. His loyalty to the Czar Alexander I resulted in his rise to A position of great prominence in the Russian service. Capodistrias saw in Alexander the saviour of Europe whose liberalizing policy would maintain A balance between the extremes of revolution and absolutism. This is the reason why Capodistrias was devoted to the Czar and the Russian service; and this is also the reason why his attitu de towards the revolutionary idea of independence for the Greeks was reserved. He was convinced that they were not yet ready for the freedom they desired ; and that only the beneficial influence of education would eventually lead to A peaceful regeneration of their nation. Events, however, were to disprove this confortable theory. They ignored his advice and finally revolted in 1821. He disapproved of the Greek resort to violence; yet he was not prepared to remain inactive. He strived to make Russian policy serve Greek ends. The re sult was that he very soon lost the trust of Alexander I. His personal ambition was not strong enough to make him deny his patriotism and remain in the Russian service.