The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verification of Vulnerable Zones Identified Under the Nitrate Directive \ and Sensitive Areas Identified Under the Urban Waste W

CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 THE URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT DIRECTIVE (91/271/EEC) 1 1.2 THE NITRATES DIRECTIVE (91/676/EEC) 3 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 4 2 THE OFFICIAL GREEK DESIGNATION PROCESS 9 2.1 OVERVIEW OF THE CURRENT SITUATION IN GREECE 9 2.2 OFFICIAL DESIGNATION OF SENSITIVE AREAS 10 2.3 OFFICIAL DESIGNATION OF VULNERABLE ZONES 14 1 INTRODUCTION This report is a review of the areas designated as Sensitive Areas in conformity with the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive 91/271/EEC and Vulnerable Zones in conformity with the Nitrates Directive 91/676/EEC in Greece. The review also includes suggestions for further areas that should be designated within the scope of these two Directives. Although the two Directives have different objectives, the areas designated as sensitive or vulnerable are reviewed simultaneously because of the similarities in the designation process. The investigations will focus upon: • Checking that those waters that should be identified according to either Directive have been; • in the case of the Nitrates Directive, assessing whether vulnerable zones have been designated correctly and comprehensively. The identification of vulnerable zones and sensitive areas in relation to the Nitrates Directive and Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive is carried out according to both common and specific criteria, as these are specified in the two Directives. 1.1 THE URBAN WASTEWATER TREATMENT DIRECTIVE (91/271/EEC) The Directive concerns the collection, treatment and discharge of urban wastewater as well as biodegradable wastewater from certain industrial sectors. The designation of sensitive areas is required by the Directive since, depending on the sensitivity of the receptor, treatment of a different level is necessary prior to discharge. -

City of Corfu : the Tranformation of the Physiognomy of a Capital City to a Provisional One Through Testimonies from Literature Athanassios BALERMPAS

reviewed paper City of Corfu : The Tranformation of the Physiognomy of a Capital City To A Provisional One Through Testimonies From Literature Athanassios BALERMPAS National Technical University of Athens, Department of Architecture and Civil Engineering, Athens, Greece, Email: [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION The historical line of a city has a significant impact in the formation of its physical and emotional physiognomy which the city projects. It plays a major part in the creation of the speech (logos) and myth (mythos) that determines each significant urban formation. Let us not forget that the speech and the myth establish the ideological foundations of a city. However, the historical context does not only influence the above two elements of its physiognomy; it also plays a central part in the formation of its society, and the architectural space is a significant factor in determining society formation, according to the theories of Rossi, Hiller and Hanson1 ; in turn both society and architecture are defined significantly by the historical and, consequently, social events. In addition, we should not forget that the inheritance of the historical events in a city determines the social, political and economic system that governs the city. His system, according to Joseph and Julia Stefanou2 , is the main factor for the physiognomy of the city, since it influences its form, style, size and development. Nobody can argue that one of Vienna’s most celebrated characteristics was the period in history when the city was the capital of the empire of the Hapsburgs. Similarly, all the other historical events that happened in the same space have also left their traces in the image of the city. -

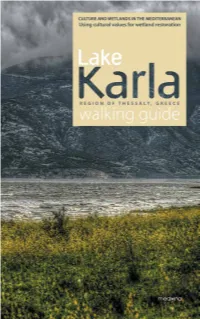

ENG-Karla-Web-Extra-Low.Pdf

231 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration 2 CULTURE AND WETLANDS IN THE MEDITERRANEAN Using cultural values for wetland restoration Lake Karla walking guide Mediterranean Institute for Nature and Anthropos Med-INA, Athens 2014 3 Edited by Stefanos Dodouras, Irini Lyratzaki and Thymio Papayannis Contributors: Charalampos Alexandrou, Chairman of Kerasia Cultural Association Maria Chamoglou, Ichthyologist, Managing Authority of the Eco-Development Area of Karla-Mavrovouni-Kefalovryso-Velestino Antonia Chasioti, Chairwoman of the Local Council of Kerasia Stefanos Dodouras, Sustainability Consultant PhD, Med-INA Andromachi Economou, Senior Researcher, Hellenic Folklore Research Centre, Academy of Athens Vana Georgala, Architect-Planner, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Ifigeneia Kagkalou, Dr of Biology, Polytechnic School, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace Vasilis Kanakoudis, Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Thessaly Thanos Kastritis, Conservation Manager, Hellenic Ornithological Society Irini Lyratzaki, Anthropologist, Med-INA Maria Magaliou-Pallikari, Forester, Municipality of Rigas Feraios Sofia Margoni, Geomorphologist PhD, School of Engineering, University of Thessaly Antikleia Moudrea-Agrafioti, Archaeologist, Department of History, Archaeology and Social Anthropology, University of Thessaly Triantafyllos Papaioannou, Chairman of the Local Council of Kanalia Aikaterini Polymerou-Kamilaki, Director of the Hellenic Folklore Research -

View Printable Flyer

J OIN FR . ROBERT H UGHES ON A P ILGRIMAGE TO GREECE IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF ST. PAUL WITH GREEK ISLES CRUISE OCTOBER 22 - NOMEVER 1, 2021 FROM EWARK HILADELPHIA Fr. Robert Hughes $4,259 N & P *PER PERSON BASED ON DOUBLE OCCUPANCY www.pilgrimages.com/frhughes/greece Book by July 31st and get $150 pp discount! Use code: restart. Santorini Delphi Meteora SAMPLE DAILY ITINERARY Day 1, Friday, October 22: Depart for Greece Day 8, Friday, October 29 : Athens - Start 3-day Cruise (Celestyal Cruises) to Syros Make your way to your local airport, where you will board your overnight flight(s). island Onboard, meals will be served to you. Following breakfast, proceed to the Piraeus port, where you will board your 3-day cruise. Your first stop will be the Island of Syros. Syros is the administrative capital of Day 2, Saturday, October 23: Arrive in Thessaloniki the Cyclades and is one of the smallest islands within the group. With its Upon landing at Makedonia Thessaloniki Airport, make your way to the baggage resplendent pastel-hued villas cascading down the Ermoupoli hill, this island is rich claim area and collect your luggage. Proceed to the arrival hall, where you will be in history and culture and provides visitors with a slice of Greek perfection without greeted by your tour guide and/-or driver. Board the bus to transfer to your hotel. the crowds. The island of Syros hosts a vast Catholic community, which reaches Enjoy some time to relax after check-in. After a delicious meal, overnight in almost half of the island's population. -

Greece: Cyclades Saronic 7-Night: Ios to Athens Ios Prior to Boarding the Boat in Ios a Visit to Santorini Is Highly Recommended As It’S the Jewel of the Cyclades

Greece: Cyclades Saronic 7-night: Ios to Athens Ios Prior to boarding the boat in Ios a visit to Santorini is highly recommended as it’s the jewel of the Cyclades. Santorini transport and accommodations are not included in the price of any boat trip and can easily be pre-arranged with Poseidon Charters. Day 1: Saturday1 Day 2: Sunday1 Arrive at Ios harbour for boarding at 17:00hrs. IOS: This is the day scheduled to tour Ios island. Rent cars or quad bikes The first two-nights are a sleepover in Ios. to explore the many wonders of the island including Homer's tomb, where the famous writer of the Greek Odyssey and the Iliad was Unpack and participate in a welcome and safety entombed following a shipwreck. briefing. Later head up to the luxury of Liostasis 5-star hotel and spa. Swim in the pool, enjoy a re-arranged Drive along the coast to popular Milopotas beach for some watersports massage or simply have cocktails and dinner watching a fantastic sunset over Ios harbor. After dinner or remote Maganari beach for a picnic lunch and swim. These are two of explore the hilltop Chora town with its many shops the finest beaches in the Aegean. and bars. Head back to the yacht for lunch then take some time to explore the early 2500BC archeological site at Skarkos - awarded the European Dinner: Liostasis’ exquisite menu Union’s prize for Cultural Heritage and Conservation in 2008. In the is prepared by a Michelin star chef afternoon, check out Pathos Café Bar’s 200ft infinity pool. -

Historical Cycles of the Economy of Modern Greece from 1821 to the Present

GreeSE Papers Hellenic Observatory Discussion Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe Paper No. 158 Historical Cycles of the Economy of Modern Greece from 1821 to the Present George Alogoskoufis April 2021 Historical Cycles of the Economy of Modern Greece from 1821 to the Present George Alogoskoufis GreeSE Paper No. 158 Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe All views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Hellenic Observatory or the LSE © George Alogoskoufis Contents I. The Major Historical Cycles of Modern Greece II. Nation Building, the ‘Great Idea’ and Economic Instability and Stagnation, 1821- 1898 II.1 The Re-awakening of the Greek National Conscience and the War of Independence II.2 Kapodistrias and the Creation of the Greek State II.3 State Building under the Regency and the Monarchy II.4 The Economy under the Monarchy and the 1843 ‘Default’ II.5 The Constitution of 1844, the ‘Great Idea’ and the End of Absolute Monarchy II.6 Changing of the Guard, Political Reforms and Territorial Gains II.7 Fiscal and Monetary Instability, External Borrowing and the 1893 ‘Default’ II.8 Transformations and Fluctuations in a Stagnant Economy III. Wars, Internal Conflicts and National Expansion and Consolidation, 1899-1949 III.1 From Economic Stabilisation to the Balkan Triumphs III.2 The ‘National Schism’, the Asia Minor Disaster and the End of the ‘Great Idea’ III.3 Political Instability, Economic Stabilisation, ‘Default’ of 1932 and Rapid Recovery III.4 From the Disaster of the Occupation to the Catastrophic Civil War III.5 Growth and Recessions from the 19th Century to World War II IV. -

Greek Isles Cruise

Greek Isles Cruise JULY 24–AUGUST 4 // 2019 ATHENS ROUNDTRIP Join the Purdue President’s Council for a ten-night cruise sailing the azure waters of the Aegean Sea to explore the ancient wonders of the Greek Isles aboard Windstar Cruises’ 310-guest sailing yacht the Wind Surf. Hail Purdue! Guest Lecturer Keith Dickson, PhD SANTORINI Professor of Classics at Purdue University WIND SURF MYKONOS THE PARTHENON CELSUS LIBRARY AT EPHESUS NAFPLIO // MYKONOS // ERMOUPOLI // KUSADASI // PATMOS // RHODES // CRETE // SANTORINI // MONEMVASIA ALL-INCLUSIVE PRESIDENT’S COUNCIL PACKAGE FEATURES » One night at the Athens Intercontinental Hotel with breakfast, » Purdue President’s Council Welcome Reception airport transfers, and evening at leisure to explore the Plaka district » Open-seating dining in a choice of four dining venues featuring » Choice of exclusive President’s Council Athens Tour with orientation specialty dining under the stars and 24-hour room service drive, Parthenon on the Acropolis, and New Acropolis Museum » All non-alcoholic drinks with an option to purchase an » Ten-night cruise aboard Windstar Cruises’ newly renovated, all-inclusive beverage package 310-guest flagship sailing yacht Wind Surf » Prepaid gratuities for ship housekeeping, bar, and dining staff » $100-per-person onboard credit (spa, shop, internet, laundry) » Watersports platform with complimentary snorkeling » Windstar Signature private moonlit dinner and orchestra concert equipment, kayaks, paddleboards, water trampoline, and more at the Celsus Library, an ancient -

The Question of Northern Epirus at the Peace Conference

Publication No, 1. THE QUESTION OF NORTHERN EPIRUS AT THE PEACE CONFERENCE BY NICHOLAS J. CASSAVETES Honorary Secretary of the Pan-Epirotie Union of America BMTKB BY CAEEOLL N. BROWN, PH.D. *v PUBLISHED FOR THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA ? WâTBB STREET, BOSTOH, MASS. BY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMERICAN BRANCH 85 WEST 32ND S1REET, NEW YÛHK 1919 THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA GENERAL COUNCIL Honorary President George Christ Zographos ( Ex-president of the Autonomous State of Epirus and formes Minister of Foreign Affairs of Greece) Honorary Secretary Nicholas J. Cassavetes President Vassilios K. Meliones Vice-President Sophocles Hadjiyannis Treasurer George Geromtakis General Secretary Michael 0. Mihailidis Assistant Secretary Evangelos Despotes CENTRAL OFFICE, ? Water Street, Room 4Î0, BOSTON, MASS. THE QUESTION OF NORTHERN EPIRUS AT THE PEACE CONFERENCE BY NICHOLAS J. CASSAVETES Honorary Secretary of the Pan-Bpirotic Union of America EDITED BY CARROLL N. BROWN, PH.D. PUBLISHED FOR THE PAN-EPIROTIC UNION OF AMERICA 7 WATER STREET, BOSTON, MASS. BY OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMERICAN BRANCH 85 WEST 82ND STREET, NEW YORK 1919 COPYIUQHT 1919 BY THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PKKSS AMERICAN BRANCH PREFACE Though the question of Northern Epirus is not pre eminent among the numerous questions which have arisen since the political waters of Europe were set into violent motion by the War, its importance can be measured neither by the numbers of the people involved, nor by the serious ness of the dangers that may arise from the disagreement of the two or three nations concerned in the dispute. Northern Epirus is the smallest of the disputed territories in Europe, and its population is not more than 300,000. -

20-0744 Top Ten Itinerary Flyers No Pricing Customizable.Indd

ANCIENT WONDERS OF GREECE & EPHESUS ATHENS TO ATHENS | 10 days SEE MORE with our Delphi & Meteora: Grecian Antiquities Cruise Tour for an extended stay in Greece. ENJOY A CRUISE WORTHY OF GREEK GODS as you visit the land of myth and legend on your own white chariot. Feast your eyes on Santorini’s Aegean Sea raven-black cliffs draped in Cyclades-blue and white homes. Inhale the scent of GREECE TURKEY heather and pines on the sacred island of Patmos, where the book of Revelation Mykonos was penned. Walk on cobblestones worn smooth by peasants and knights in the Ermoupoli Kusadasi living medieval cities of Rhodes and Monemvasia. Stray off the beaten path Piraeus (Athens) to Ermoupoli where the strains of rebetiko (Greek blues) flow from open-air Nafplio Patmos tavernas, and to Agios Nikolaus, to swim in the lagoon where the goddess Athena was said to bathe. Blur the lines between dreams and reality as you dine in the Santorini Rhodes shadow of Ephesus at a complimentary Destination Discovery Event. Each day Monemvasia Agios Nikolaos adds a new page as you write your own legend. Mediterranean Sea POPULAR HIGHLIGHTS ITINERARY • Tour the Parthenon and the Acropolis in Athens, which are must-sees Day 1 Piraeus (Athens), Greece • Take advantage of late nights in Crete and Rhodes for an even better sense of the local flavor Day 2 Nafplio, Greece • Watch the thatched-roof working windmills, shop the chic boutiques and cafés, and relax Day 3 Mykonos, Greece on the beach on Mykonos Day 4 Ermoupoli, Greece Day 5 Kusadasi, Turkey • See forever memorable -

Visa & Residence Permit Guide for Students

Ministry of Interior & Administrative Reconstruction Ministry of Foreign Affairs Directorate General for Citizenship & C GEN. DIRECTORATE FOR EUROPEAN AFFAIRS Immigration Policy C4 Directorate Justice, Home Affairs & Directorate for Immigration Policy Schengen Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.ypes.gr www.mfa.gr Visa & Residence Permit guide for students 1 Index 1. EU/EEA Nationals 2. Non EU/EEA Nationals 2.a Mobility of Non EU/EEA Students - Moving between EU countries during my short-term visit – less than three months - Moving between EU countries during my long-term stay – more than three months 2.b Short courses in Greek Universities, not exceeding three months. 2.c Admission for studies in Greek Universities or for participation in exchange programs, under bilateral agreements or in projects funded by the European Union i.e “ERASMUS + (placement)” program for long-term stay (more than three months). - Studies in Greek universities (undergraduate, master and doctoral level - Participation in exchange programs, under interstate agreements, in cooperation projects funded by the European Union including «ERASMUS+ placement program» 3. Refusal of a National Visa (type D)/Rights of the applicant. 4. Right to appeal against the decision of the Consular Authority 5. Annex I - Application form for National Visa (sample) Annex II - Application form for Residence Permit Annex III - Refusal Form Annex IV - Photo specifications for a national visa application Annex V - Aliens and Immigration Departments Contacts 2 1. Students EU/EEA Nationals You will not require a visa for studies to enter Greece if you possess a valid passport from an EU Member State, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway or Switzerland. -

The Historical Review/La Revue Historique

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by National Documentation Centre - EKT journals The Historical Review/La Revue Historique Vol. 11, 2014 Index Hatzopoulos Marios https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 Copyright © 2014 To cite this article: Hatzopoulos, M. (2014). Index. The Historical Review/La Revue Historique, 11, I-XCII. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/hr.339 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX, VOLUMES I-X Compiled by / Compilé par Marios Hatzopoulos http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 21/02/2020 08:44:40 | INDEX Aachen (Congress of) X/161 Académie des Inscriptions et Belles- Abadan IX/215-216 Lettres, Paris II/67, 71, 109; III/178; Abbott (family) VI/130, 132, 138-139, V/79; VI/54, 65, 71, 107; IX/174-176 141, 143, 146-147, 149 Académie des Sciences, Inscriptions et Abbott, Annetta VI/130, 142, 144-145, Belles-Lettres de Toulouse VI/54 147-150 Academy of France I/224; V/69, 79 Abbott, Bartolomew Edward VI/129- Acciajuoli (family) IX/29 132, 136-138, 140-157 Acciajuoli, Lapa IX/29 Abbott, Canella-Maria VI/130, 145, 147- Acciarello VII/271 150 Achaia I/266; X/306 Abbott, Caroline Sarah VI/149-150 Achilles I/64 Abbott, George Frederic (the elder) VI/130 Acropolis II/70; III/69; VIII/87 Abbott, George Frederic (the younger) Acton, John VII/110 VI/130, 136, 138-139, 141-150, 155 Adam (biblical person) IX/26 Abbott, George VI/130 Adams, -

Greece, Port Facility Number

GREECE Approved port facilities in Greece IMPORTANT: The information provided in the GISIS Maritime Security module is continuously updated and you should refer to the latest information provided by IMO Member States which can be found on: https://gisis.imo.org/Public/ISPS/PortFacilities.aspx Port Name 1 Port Name 2 Facility Name Facility Description Longitude Latitude Number AchladiAggersund AchladiAggersund AGROINVESTAggersund - Aggersund S.A., ACHLADI- Kalkvaerk GRACL-0001DKASH-0001 UNLOADING/LOADINGBulk carrier 0224905E0091760E 385303N565990N FTHIOTIS-GREECE GRAINS,OIL SEED AND PRODUCT DERIVED OF Agia Marina Agia Marina HELLENIC MINING ENTERPRISES GRAGM-0001 BEAUXITE MINING 0223405E 355305N S.A. Alexandroupolis AEGEAN OIL GR932-0003 STORAGE AND DISTRIBUTION 0255475E 405034N OF PETROLEUM PRODUCTS Alexandroupolis XATZILUCAS COMPANY GR932-0005 STORAGE AND DISTRIBUTION 0255524E 404952N OF ETHANOL Alexandroúpolis Alexandroupolis COMMERCIAL PORT GRAXD-0001 Commercial port 0255405E 405004N ALEXANDROUPOLIS Aliverio Aliverio PPC ALIVERI SES PORT GRLVR-0001 PEER FOR DISCHARGING OF HFO 0240291E 382350N TO ALIVERI STEAM ELECTRIC STATION Amfilochía Amfilochia AMFILOCHIA GRAMF-0001 COMMERCIAL PORT 0211003E 385106N Antikyra Antikyra DIA.VI.PE.THI.V. S.A. GRATK-0004 COMMERCIAL PORT/ 0225701E 381319N PRODUCTION IRON PIPES Antikyra Antikyra SAINT NIKOLAOS VOIOTIAS - GRATK-0001 ALOUMINION PRODUCTION AND 0224108E 382157N ALOUMINION S.A TRADE Apollonía Apollonia KAMARES SIFNOU GRSIF-0001 PASSENGER PORT 0244020E 365940N Argostólion Argostolion ARGOSTOLI-KEFALLONIA GRARM-0001 MAINLY PASSENGER PORT- 0212950E 381110N TRANSPORTATION OF SMALL QUANTITIES OF CARGO AND PETROL Aspropirgos Aspropirgos HELLENIC FUELS S.A GRASS-0001 LOADING/DISCHARGE OF 0233537E 380120N ASPROPYRGOS REFINED PETROLEUM PRODUCTS(GASOLINE, GAS OIL, AVIATION FUELS) Aspropirgos Aspropirgos HELLENIC PETROLEUM- GRASS-0002 LOADING AND UNLOADING OF 0233541E 380147N ASPROPYRGOS ALL PETROLEUM PRODUCTS Aspropirgos Aspropirgos MELCO PETROLEUM S.A.