Recreational Fishing in Commonwealth Waters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bushwalk Australia

Bushwalk Australia Staying Home Volume 40, April 2020 2 | BWA April 2020 Bushwalk Australia Magazine An electronic magazine for http://bushwalk. com Volume 40, April 2020 We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of this vast land which we explore. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present, and thank them for their stewardship of this great south land. Watching nature from my couch Matt McClelland Editor Matt McClelland [email protected] Design manager Eva Gomišček [email protected] Sub-editor Stephen Lake [email protected] Please send any articles, suggestions or advertising enquires to Eva. BWA Advisory Panel North-north-west Mark Fowler Brian Eglinton We would love you to be part of the magazine, here is how to contribute - Writer's Guide. The copy deadline for the June 2020 edition is 30 April 2020. Warning Like all outdoor pursuits, the activities described in this publication may be dangerous. Undertaking them may result in loss, serious injury or death. The information in this publication is without any warranty on accuracy or completeness. There may be significant omissions and errors. People who are interested in walking in the areas concerned should make their own enquiries, More than one way and not rely fully on the information in this publication. 6 The publisher, editor, authors or any other to climb Mount Giles entity or person will not be held responsible for any loss, injury, claim or liability of any kind resulting from people using information in this publication. Please consider joining a walking club or undertaking formal training in other ways to Look at the Sun ensure you are well prepared for any activities you are planning. -

Nowhere Else on Earth

Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values Environment Tasmania is a not-for-profit conservation council dedicated to the protection, conservation and rehabilitation of Tasmania’s natural environment. Australia’s youngest conservation council, Environment Tasmania was established in 2006 and is a peak body representing over 20 Tasmanian environment groups. Prepared for Environment Tasmania by Dr Karen Parsons of Aquenal Pty Ltd. Report citation: Parsons, K. E. (2011) Nowhere Else on Earth: Tasmania’s Marine Natural Values. Report for Environment Tasmania. Aquenal, Tasmania. ISBN: 978-0-646-56647-4 Graphic Design: onetonnegraphic www.onetonnegraphic.com.au Online: Visit the Environment Tasmania website at: www.et.org.au or Ocean Planet online at www.oceanplanet.org.au Partners: With thanks to the The Wilderness Society Inc for their financial support through the WildCountry Small Grants Program, and to NRM North and NRM South. Front Cover: Gorgonian fan with diver (Photograph: © Geoff Rollins). 2 Waterfall Bay cave (Photograph: © Jon Bryan). Acknowledgements The following people are thanked for their assistance The majority of the photographs in the report were with the compilation of this report: Neville Barrett of the generously provided by Graham Edgar, while the following Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the additional contributors are also acknowledged: Neville University of Tasmania for providing information on key Barrett, Jane Elek, Sue Wragge, Chris Black, Jon Bryan, features of Tasmania’s marine -

Bushwalk Australia

Bushwalk Australia Hills & Valleys Volume 38, December 2019 2 | BWA December 2019 Bushwalk Australia Magazine An electronic magazine for bushwalk.com Volume 38, December 2019 We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of this vast land which we explore. We pay our respects to their Elders, past and present, and thank them for their stewardship of this great south land. Cover picture Camping high has its rewards - Crepuscular rays over Pokana Peak MJD Editor Matt McClelland [email protected] Design manager Eva Gomišček [email protected] Sub-editor Stephen Lake [email protected] Please send any articles, suggestions or advertising enquires to Eva. Orange Bluff via BWA Advisory Panel North-north-west 6 Great Stony Mountain Mark Fowler Brian Eglinton Best resting spot We would love you to be part of the magazine, here is how to contribute - Writer's Guide. Two State 8 peaks The copy deadline for the Two of the highest February 2020 edition is 12 31 December 2019. peaks in Australia Warning Sassafras to Wog Wog Like all outdoor pursuits, the activities described in this publication may be 18 The Budawangs - where you dangerous. Undertaking them may result in loss, serious injury or death. can get lost in time The information in this publication is without any warranty on accuracy or completeness. There may be significant omissions and errors. People who are interested in walking in the areas Grose Valley concerned should make their own enquiries, and not rely fully on the A bushwalk in information in this publication. 24 The publisher, editor, authors or any Blue Mountains other entity or person will not be held responsible for any loss, injury, claim or liability of any kind resulting from people using information in this publication. -

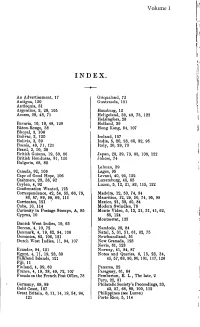

016678184 Philatelicrecord In

Volume 1 INDEX. Ail Advertisement, 17 Griqualand, 72 Antigua, 120 Guatemala, 121 Antioquia, 81 Argentine, 3, 28, 105 Hamburg, 12 Azores, 28, 48, 71 Heligoland, 39, 49, 73, 122 Helsingfors, 28 Bavaria, 10, 19, 48, 120 Holland, 39 Baton-Rouge, 38 Hong Kong, 94, 107 Bhopal, 3, 100 Bolivar, 3, 120 Iceland, 107 Bolivia, 3, 59 India, 5, 20, 28, 60, 82, 95 Bosnia, 49, 71, 121 Italy, 20, 39, 73 Brazil, 3, 10, 38 British Guiana, 19, 59, 80 Japan, 20, 39, 73, 83, 108, 122 British Honduras, 81, 120 Johore, 74 Bulgaria, 48, 82 Labuan, 39 Canada, 92, 106 Lagos, 95 Cape of Good Hope, 106 Levant, 40, 95, 122 Cashmere, 28, 38, 92 Luxemburg, 40, 83 Ceylon, 4, 92 Luzon, 5, 12, 21, 83, 115, 122 Confirmation Wanted, 125 Correspondence, 42, 54, 55, 66, 79, Madeira, 12, 50, 74, 84 80, 87, 89, 98, 99, 111 Mauritius, 12, 29, 50, 74, 95, 98 Corrientes, 121 ' Mexico, 21, 30, 40, 84 Cuba, 10, 114 Modern Swindles, 78 Curiosity in Postage Stamps, A, 85 Monte Video, 5, 13, 21, 31, 41, 62, Cyprus, 10 85, 124 Montserrat, 123 Danish West Indies, 19, 93 Deccan, 4, 10, 72 Nandode, 20, 84 Denmark, 4, 19, 82, 94, 106 Natal, 5, 31, 51, 61, 62, 75 Dominica, 82, 106, 121 Newfoundland, 51 Dutch West Indies, 11, 94, 107 New Granada, 123 Nevis, 61, 123 Ecuador, 94, 121 Norway, 41, 84, 87 Egypt, 4, 11, 19, 28, 38 Notes and Queries, 6, 15, 23, 34, Falkland Islands, 121 45, 57, 68, 80, 90,101, 117, 126 Fiji, 11 Finland, 4, 39, 60 Panama, 22 France, 4, 19, 38, 49, 72, 107 Paraguay, 61, 84 Frauds on the French Post Office, 78 Pemberton, E. -

Tasmanian Natural Resource Management (NRM) Framework and Legislation

Review of the Tasmanian Natural Resource Management (NRM) Framework and Legislation 2007Discussion Paper Depar tment of Primar y Industries and Water Public comment invited You can submit your The Review comments: The Tasmanian Natural Resource Management (NRM) Framework is being reviewed five years after it was established. This fulfils a commitment made in the original NRM Framework document and implements a specific Online at: provision in the Framework’s enabling legislation, the Natural Resource www.dpiw.tas.gov.au/nrmreview Management Act 2002. By email at: [email protected] The Department of Primary Industries and Water is conducting the Review, By post to: with assistance from the NRM Council. In accordance with the Terms of The Executive Officer Reference issued by the Minister for Primary Industries and Water (see NRM Review Appendix 1), a report will be submitted to him by 29 February 2008. GPO Box 44 Hobart TAS 7001 This Discussion Paper is the core of the public consultation process for this Review. It provides background information and invites views and comments, especially from people who have observed, or worked with, Submissions will be accepted until the NRM arrangements that have been established under the NRM 26 October 2007. Framework. The content of submissions may be made public, and information The focus questions contained in submissions may be The Discussion Paper addresses the specific issues highlighted in the Terms provided to an applicant under of Reference. It includes a focus question for each issue, to assist people the provisions of the Freedom of to focus their input to the Review. -

An Atlas of Commercial Geography

IO?-5 AN ATLAS OF COMMERCIAL GEOGRAPHY % % "i % ¥ .i. J- >- %t ST'' .T. CAMBRIDGE ^ UNIVERSITY PRESS a^^^^^^^^^^^ggSgfjSjSjSigHiasH^^^^^^^a^^^^^^^^^li^gigaa Dtate Collese of iKgricuUure m Cornell ^Hnibersitp Stfjaca, i5. g. ILibrarp """^'^'>y HF 1023.A4°'"^" Library llMl!™™,f,,°'<=°'"'"ei-cialc Cornell University Library V, The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013803618 AN ATLAS OF COMMERCIAL GEOGRAPHY ; INTRODUCTION THIS Atlas is specially intended to be used with the for the tropics, but is useful as indicating the significance Elementary Commercial Geography published by the of the great lowland areas which characterise the tem- Cambridge University Press, but it is hoped that such perate zones. a series of maps, illustrating the elementary facts of eco- In the tropics, as mentioned, climatic conditions nomic geography, will be of general use to students. The favour the gi'owth of population rather on the highlands work falls into two broad divisions ; the first containing than the lowlands; but the difficulties of communication maps presenting facts on the world-scale, on which the retard the commercial development of the former areas. teaching of principles may be based ; the second giving a P. 4. In using these maps, it should first be made consistent series of maps for each continent, sufficiently clear that the temperatures shown are reduced to sea- detailed, it is hoped, to be of use for regional stud}'. level, and some idea of the effect of altitude on tempera- The object of this Introduction is to indicate a logical ture given—in general terms, that the latter diminishes method of study, by linking facts together in a natural by 1°F. -

Radiation Oncology Areas of Need: Cancer Incidence Projections 2014-2024

Radiation oncology areas of need: cancer incidence projections 2014–2024 presents cancer incidence Radiation oncology areas of need projections at the jurisdictional health planning region level for 2014 to 2024. These projections were developed cancer incidence projections 2014–2024 specifically for Australian Government Department of Health planning purposes. CANCER SERIES NO. 85 CANCER SERIES Number 85 Radiation oncology areas of need Cancer incidence projections 2014–2024 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Canberra Cat. no. CAN 82 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare is a major national agency which provides reliable, regular and relevant information and statistics on Australia’s health and welfare. The Institute’s mission is authoritative information and statistics to promote better health and wellbeing. © Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2014 This product, excluding the AIHW logo, Commonwealth Coat of Arms and any material owned by a third party or protected by a trademark, has been released under a Creative Commons BY 3.0 (CC–BY 3.0) licence. Excluded material owned by third parties may include, for example, design and layout, images obtained under licence from third parties and signatures. We have made all reasonable efforts to identify and label material owned by third parties. You may distribute, remix and build upon this work. However, you must attribute the AIHW as the copyright holder of the work in compliance with our attribution policy available at <www.aihw.gov.au/copyright/>. The full terms and conditions of this licence are available at <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/>. Enquiries relating to copyright should be addressed to the Head of the Media and Strategic Engagement Unit, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, GPO Box 570, Canberra ACT 2601. -

Australian and American Perspectives on the Protection of Solar and Wind Access

Volume 28 Issue 2 Spring 1988 Spring 1988 Australian and American Perspectives on the Protection of Solar and Wind Access Adrian J. Bradbrook Recommended Citation Adrian J. Bradbrook, Australian and American Perspectives on the Protection of Solar and Wind Access, 28 Nat. Resources J. 229 (1988). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol28/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. ADRIAN J. BRADBROOK* Australian and American Perspectives on the Protection of Solar and Wind Access INTRODUCTION There is considerable potential in both Australia and the United States for the development of solar and wind energy. Except for Alaska, both countries lie within the latitude range of 50°N to 50°S. Research has shown that every country within this latitude range receives sufficient quantities of direct solar insolation for commercial exploitation,' and the prospects are particularly favorable in the sunbelt area of the United States and large tracts of northern and central Australia.2 The wind resource potential in both countries is also impressive. In the United States, the Solar Energy Research Institute stated in a 1980 report that there are 3.8 million homes, mostly in rural areas, and 370,000 farms in good locations for wind machines. The report further stated that there is a potential $25 billion market3 for wind generators and that the United States could eventually have five million small wind generators with a total generating capacity of 25 gigawatts.' In Australia, the National Energy Advisory Council has reported that favorable sites for wind energy generation exist in coastal areas, particularly along the south coast of the continent and the west coast of Tasmania. -

Fact Sheet: the Indian Ocean Region and Australia's National Interests

29 May 2012 Fact Sheet: The Indian Ocean Region and Australia’s National Interests Sergei DeSilva-Ranasinghe Research Manager, South & West Asia Programme Summary Not since the Cold War has events in the Indian Ocean Region resonated so much in Australia. Based on extensive research, this reference document is designed to provide an readily accessible source of information to assist Australian policymakers to better understand the Indian Ocean Region.1 Analysis Geopolitical Characteristics of the Indian Ocean Region The Indian Ocean Region contains 36 littoral and 14 adjacent hinterland states, consisting of more than 2.6 billion people or 40 per cent of the world’s population.2 The Indian Ocean Region is fraught with strategic competition and is considered one of the most nuclearised of the world’s oceans with eight nuclear powers active in its waters: US, Russia, China, France, UK, India, Pakistan and Israel.3 1 The Indian Ocean Region should not be confused with the Indian Ocean Rim, a term which refers to the littoral states of the Indian Ocean, but not the region’s interconnected hinterland states. For further reference see Rumley, D., Doyle, T., and Chaturvedi, S., ‘Securing’ the Indian Ocean? Competing Regional Security Constructions, Indo-Pacific Governance Research Centre: Adelaide, April 2012. Similarly, the term Indo-Pacific tends to emphasise either the Indian and Pacific oceans as one interlinked region or simply identifies India and South Asia as being linked to the Asia-Pacific region. 2 The Indian Ocean Region’s littoral states are: Bahrain, Bangladesh, Burma, Comoros, Djibouti, East Timor, Egypt, Eritrea, France (Reunion and Mayotte), India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Madagascar, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritius, Mozambique, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Seychelles, Singapore, Somalia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. -

John Gilchrist Thesis (PDF 1MB)

THE GOVERNMENT AS PROPRIETOR, PRESERVER AND USER OF COPYRIGHT MATERIAL UNDER THE COPYRIGHT ACT 1968 (CTH) by John Steel Gilchrist Barrister and Solicitor of the High Court of Australia and of the Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory BA, LLB, LLM (Mon) GCHE (UC) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Queensland University of Technology 2012 IN MEMORIAM Ian Steel Gilchrist and Violet Cherry Burnell Gregory STATEMENT OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made. Signature QUT Verified Signature Date: 111 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the role of government as proprietor, preserver and user of copyright material under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) and the policy considerations which Australian law should take into account in that role. There are two recurring themes arising in this examination which are significant to the recommendations and conclusions. The first is whether the needs and status of government should be different from private sector institutions, which also obtain copyright protection under the law. This theme stems from the 2005 Report on Crown Copyright by the Copyright Law Review Committee and the earlier Ergas Committee Report which are discussed in Chapters 2 and 8 of this thesis. The second is to identify the relationship between government copyright law and policy, national cultural policy and fundamental governance values. -

The Life of Sir Garfield Barwick

The life of Sir Garfield Barwick A blot on Bolt Invalidating' the Malaysian Solution Duty of care on the battlefield Bullfry at the end of the dinner Vale Simon Kerr SC Contents 2 Editor’s note 4 President’s column 6 Bar Practice Course 02/2011 7 Letter to the editor 8 Opinion The failed art of sentencing offenders Reflections on concurrent expert evidence From hack to senior junior A blot on Bolt 22 Recent developments 53 Feature Bullfry at the end of the dinner. Duty of care on the battlefield 59 Practice 77 St Vincent de Paul Fundraiser 96 Obituaries 62 Address 78 Legal history Alec Shand QC Simon Kerr SC The life and career of Sir Garfield Barristers in Second World War Barwick (Part I) 103 Bullfry 70 Bar art 92 Appointments 105 Rapunzel Portrait of Sir Kenneth Jacobs The Hon Justice Meagher 106 Book reviews 74 Tutors and Readers Dinner The Hon Justice Adamson 114 Bar sports 75 Clerks Conference Dinner 120 The Bar Book Club 76 Bar History Project launch barTHE JOURNAL OF THE NSWnews BAR ASSOCIATION | SUMMER 2011–12 Bar News Editorial Committee ISSN 0817-0002 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, and subsequent amendments, Andrew Bell SC (editor) Views expressed by contributors to Bar no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system Keith Chapple SC News are not necessarily those of the New or transmitted by any means or process without specific Arthur Moses SC South Wales Bar Association. Contributions written permission from the copyright owner. -

EDLINS AUCTIONS Auction No 228 (New Date) Saturday 28 August 2021 Postal Or Absentee Bids Only Due to Covid-19 Lockdown

EDLINS AUCTIONS Auction No 228 (New Date) Saturday 28 August 2021 Postal or Absentee Bids Only Due to Covid-19 Lockdown Lot 813 Lot 814 Lot 815 $5 LOT 26 LOT 29 LOT 132 LOT 42 LOT 55 LOT 96 LOT 91 LOT 93 LOT 97 LOT 98 LOT 99 LOT 108 LOT 114 2 • EDLINS AUCTION 228 EDLINS AUCTIONS Postal Auction No. 228 Saturday (NEW DATE) 28 August 2021 Viewing of Lots Canberra Store Limited viewing by appointment (Phone 02 62487859) Saturday 7 August, Monday 9 August and Tuesday 10 August. No Box lots or accumulations may be viewed at the Canberra store. Viewing is limited to single country collections or single carded or enveloped lots. A list of lots that you wish to view must be sent via email or phoned through when booking your viewing time. Please note excessively long lists of lots may not be available for viewing and viewing time slots will be limited to 3 hours per person per day. A Covid-19 check in is required before entry to the Auction Rooms. Masks will be provided and may be required to be worn whilst in the viewing area. Please make yourself aware of all current Health warnings Please help us by abiding by any verbal instructions whilst in the Auction Rooms Yass Store General viewing by appointment (Phone 02 62261555) General viewing of lots takes place at our Shop/Office premises located at 157 Comur Street Yass NSW 2582 viewing of Lots is only available by appointment. Wednesday 11 August, Thursday 12 August & Friday 13 August (By appointment only) Please note viewing time slots will be limited to 3 hours per person per day.