Linguistic Appropriation of Slang Terms Within the Popular Lexicon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Formation of Mass Incarceration

The Biography of an Institution: The Cultural Formation of Mass Incarceration Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicole Barnaby, B. A. Graduate Program in African American and African Studies The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Devin Fergus, Advisor Denise Noble Lynn Itagaki Copyright by Nicole Barnaby 2016 Abstract It may be hard for some to justify how the United States imprisons over two million people when it is hailed ‘the land of the free,’ but this thesis argues that there are very real social, economic and political drivers behind this growing trend having nothing to do with crime. While mass incarceration has its roots in other older forms of racialized social control, it exists in its current form due to an array of cultural conditions which foster its existence. Utilizing the cultural studies tool known as the circuit of culture, this thesis aims to provide a holistic understanding of the articulation of social factors contributing to the existence of mass incarceration. In order to do this, mass incarceration is assessed with the use of the 5 processes of the circuit of culture (production, regulation, representation, consumption and identity) and a specific look at its relation to the Black community over time is considered. ii Vita 2012…………………………B. A. Sociology, University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth 2014-present......................Graduate Teaching Associate, Department of African American and African -

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent Vs. Sign to a Label: Artist's Point of View

Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to a Label: Artist’s Point of View Sampo Winberg Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in International Business 2018 Abstract Date 22.5.2018 Author(s) Sampo Winberg Degree programme International Business Report/thesis title Number of pages Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent vs. Sign to and appendix pages a Label: Artist’s Point of View 58 + 6 The mark of an artist making it in music industry, throughout its relatively short history, has always been a record deal. It is a ticket to fame and seen as the only way to make a living with your music. Most artist would accept a record deal without hesitating. Being an artist myself I fall into the same category, at least before conducting this research. As we know record labels tend to take a decent chunk of artists’ revenues. Goal of this the- sis is to find out ways how a modern-day artist makes money, and can it be done so that it would be better to remain as an independent artist. What is the difference in volume that artist needs without a label vs. with a label? Can you get enough exposure and make enough money that you can manage without a record label? Technology has been and still is the single most important thing when it comes to the evo- lution of the music industry. New innovations are made possible by constant technological development and they’ve revolutionized the industry many times. First it was vinyl, then CD, MTV, Napster, iTunes, Spotify etc. -

Shot to Death at the Loft

SATURDAY • JUNE 12, 2004 Including The Bensonhurst Paper Brooklyn’s REAL newspapers Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2004 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages • Vol. 27, No. 24 BRZ • Saturday, June 19, 2004 • FREE Shot to death at The Loft By Jotham Sederstrom Police say the June 12 shooting happened in a basement bathroom The Brooklyn Papers about an hour before the bar was to close. Around 3 am, an unidentified man pumped at least four shots into A man was shot to death early Saturday morning in the bath- Valdes, who served five years in prison after an arrest for robbery in room of the Loft nightclub on Third Avenue in Bay Ridge. 1989, according to Kings County court records. The gunman, who has Mango / Greg Residents within earshot of the club at 91st Street expressed concern thus far eluded police, may have slipped out the front door after climb- but not surprise at the 3 am murder of Luis Valdes, a Sunset Park ex- ing the stairs from the basement, say police. convict. Following the murder, Councilman Vincent Gentile voiced renewed “That stinkin’ place on the corner,” said Ray Rodland, who has lived support for legislation that would allow off-duty police officers to moon- on 91st Street between Second and Third avenues for 20 years. “Even light as bouncers — in uniform — at bars and restaurants. The bill is Papers The Brooklyn if you’re farther away, at 4 in the morning that boom-boom music currently stalled in a City Council subcommittee for public housing. -

Rupaul's Drag Race All Stars Season 2

Media Release: Wednesday August 24, 2016 RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE ALL STARS SEASON 2 TO AIR EXPRESS FROM THE US ON FOXTEL’S ARENA Premieres Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm Hot off the heels of one of the most electrifying seasons of RuPaul’s Drag Race, Mama Ru will return to the runway for RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 and, in a win for viewers, Foxtel has announced it will be airing express from the US from Friday, August 26 at 8.30pm on a new channel - Arena. In this second All Stars instalment, YouTube sensation Todrick Hall joins Carson Kressley and Michelle Visage on the judging panel alongside RuPaul for a season packed with more eleganza, wigtastic challenges and twists than Drag Race has ever seen. The series will also feature some of RuPaul’s favourite celebrities as guest judges, including Raven- Symone, Ross Matthews, Jeremy Scott, Nicole Schedrzinger, Graham Norton and Aubrey Plaza. Foxtel’s Head of Channels, Stephen Baldwin commented: “We know how passionate RuPaul fans are. Foxtel has been working closely with the production company, World of Wonder, and Passion Distribution and we are thrilled they have made it possible for the series to air in Australia just hours after its US telecast.” RuPaul’s Drag Race All Stars Season 2 will see 10 of the most celebrated competitors vying for a second chance to enter Drag Race history, and will be filled with plenty of heated competition, lip- syncing for the legacy and, of course, the All-Stars Snatch Game. The All Stars queens hoping to earn their place among Drag Race Royalty are: Adore Delano (S6), Alaska (S5), Alyssa Edwards (S5), Coco Montrese (S5), Detox (S5), Ginger Minj (S7), Katya (S7), Phi Phi O’Hara (S4), Roxxxy Andrews (S5) and Tatianna (S2). -

Government .Shuts Down 40-Billion

- � HARPERNEws HARPER HUB 11:=.. , tn harbinger.harpercollege.edu Monday,October 7, 2013 46THYEAR . ISSUETHREE I FREE Government .Shuts Down 40-billion By Michelle Czaja a Hanan Aqull one key duty in the Constitution, four years ago, yet Republicans shutdown over Obamacare is New_sEditor & OfficeManager to pass spending bills that fund are trying to revoke the law. unnecessary. Wion states, "The dollar c.ut the. government. If it does not, According to CNN, "The Patient purpose of Obamacare is to America facesthe biggest ordeal most functions of government, Protection and Affordable Care expand coverage and lower cost yet, as the government shuts from funding agencies to paying Act, the actual name of the law, for consumers and the country. on food down.People all around the world out small business loans and requites ·au Americans to have It does expand coverage but it is are puzzled as the government processing passport requests health insurance." For the first debatable as to whether it lowers shut down on Tuesday morning, grind to a halt. Some services year, citizens will be taxed $95. For cost." stamps Oct. 1. like Social Security, air traffic every consecutive year, the tax will Harper students are not Republicans and Democrats control and active military 'pay, continue to increase. affected greatly by the shutdown. By Juan Cervantes could not agree on a spending will continue to be funded, as the Americans question whether Social services such as passports Sta.ffWriter plan.for the fiscal year that started Congress still gets paid," according the government shutdown is are closed, however, unless you Tuesday as they wrangled over to CNN. -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad. -

Ing the Art O Hi R

FREE.WEEKLY. VOLUME VOLUME 71 // ISSUE 25 // MAR 23 TimaTe n he art o i inG t f s lor hi s exp Ba k T r o i n dininG out with Golden key BudGet cut special diets p8 questions p15 quandary p18 The official s TudenT newspaper of The universiTy of winnipeg CDI_Winnipeg_Uniter_Feb2017_ACSW.pdf 1 2017-03-01 10:44 AM ASK ABOUT OUR EVENING CLASSES! The UniTer // March 23, 2017 3 on the cover emma Bedard began taking part in shibari when she moved from a northern Manitoba community less than a year ago. WHAT’S IN A JOB? an addictions & We’re hiring another position for the fall – and per- haps some of you are wondering, “Why does The Uniter hire so often? Is there some nasty secret here in the basement of the Bulman Centre that C community drives aspiring writers and journalists away?” M There is one specific reason why we seem Y services worker to hire more often (and have staff changing positions more often) than other news outlets. It CM all comes back to our role as a learning paper. MY We’re here to help build careers, not to CY TUITION SCHOLARSHIP* $3,000 sustain them for years upon years. We hold CMY professional standards and collaborate with each other to help meet them. But the end goal isn’t K Want to become an addictions support worker? CDI to have a super-experienced crew who can do perfect journalism, if such a thing even exists. College’s Winnipeg campus is offering a $3,000 tuition Our positions are created specifically so scholarship* for the Addictions & Community Services writers, editors and visual creatives can learn Worker program. -

Jeremias Lucas Tavares

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE CAMPINA GRANDE CENTRO DE HUMANIDADES UNIDADE ACADÊMICA DE LETRAS CURSO DE LICENCIATURA EM LETRAS: LÍNGUA INGLESA JEREMIAS LUCAS TAVARES PERFORMANCE E LINGUAGEM DRAG EM RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE: UM ESTUDO SOBRE REPRESENTAÇÃO ATRAVÉS DE LEGENDAS E TRADUÇÃO INTERSEMIÓTICA. CAMPINA GRANDE - PB 2019 JEREMIAS LUCAS TAVARES PERFORMANCE E LINGUAGEM DRAG EM RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE: UM ESTUDO SOBRE REPRESENTAÇÃO ATRAVÉS DE LEGENDAS E TRADUÇÃO INTERSEMIÓTICA. Monografia apresentada ao Curso de Licenciatura em Letras - Língua Inglesa do Centro de Humanidades da Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Licenciado em Letras – Língua Inglesa. Orientadora: Professora Dra. Sinara de Oliveira Branco. CAMPINA GRANDE - PB 2019 JEREMIAS LUCAS TAVARES PERFORMANCE E LINGUAGEM DRAG EM RUPAUL’S DRAG RACE: UM ESTUDO SOBRE REPRESENTAÇÃO ATRAVÉS DE LEGENDAS E TRADUÇÃO INTERSEMIÓTICA Monografia de conclusão de curso apresentada ao curso de Letras – Língua Inglesa da Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, como requisito parcial à conclusão do curso. Aprovada em 11 de Julho de 2019 Banca Examinadora: _______________________________________________________________ Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Sinara de Oliveira Branco – UFCG _______________________________________________________________ Profa. Dra. Danielle Dayse Marques de Lima – UFCG _______________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Suênio Stevenson Tomaz da Silva – UFCG Campina Grande - PB 2019 AGRADECIMENTOS Primeiramente, gostaria de agradecer a essa força – ainda tão pouco explicada – que foi batizada com diversos nomes no decorrer da história da humanidade e que eu gosto de me referir como natureza. Toda minha vida fui guiado por essa força – nunca estive só. Quero agradecer à minha família – minhas duas mães, Finha e Dona Donzica, meu irmão, Jonas e minha cunhada, Day – que sempre me amaram e torceram por mim. -

Rethinking the Circuit of Culture: How Participatory Culture

G Model PUBREL-1549; No. of Pages 12 ARTICLE IN PRESS Public Relations Review xxx (2016) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Public Relations Review Rethinking the circuit of culture: How participatory culture has transformed cross-cultural communication ∗ Bridget Tombleson , Katharina Wolf Curtin University, Perth, GPO Box U1987 WA 6845, Australia a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Available online xxx This paper explores the influence of digital communication − and in particular social media − on cross-cultural communication, based on the Circuit of Culture model. Scholarly litera- ture supports the notion that social media has changed the speed at which we communicate, Keywords: as well as removed traditional (geographical) boundaries around cross-cultural campaigns. Circuit of culture Since the introduction of digital media, the role of the public relations practitioner has Participatory culture become more strategic in order to maintain relevance with even more diverse − and Hashtag activism dispersed − audiences. Large scale campaigns, like the Human Rights Campaign to sup- Co-creation port Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) rights, have seen messages spread far Cross-cultural communication beyond the country of origin, and with that, demonstrate the ability to affect advocacy Cultural curator campaigns in other countries. The authors argue that instead of acting as cultural inter- mediaries, public relations practitioners must become cultural curators, with the skills to create meaning from audiences, who are now content creators in their own rights, and encourage a true participatory environment that sees cultural values shared as part of an organic exchange process. -

“Over-The-Top” Television: Circuits of Media Distribution Since the Internet

BEYOND “OVER-THE-TOP” TELEVISION: CIRCUITS OF MEDIA DISTRIBUTION SINCE THE INTERNET Ian Murphy A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Richard Cante Michael Palm Victoria Ekstrand Jennifer Holt Daniel Kreiss Alice Marwick Neal Thomas © 2018 Ian Murphy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Ian Murphy: Beyond “Over-the-Top” Television: Circuits of Media Distribution Since the Internet (Under the direction of Richard Cante and Michael Palm) My dissertation analyzes the evolution of contemporary, cross-platform and international circuits of media distribution. A circuit of media distribution refers to both the circulation of media content as well as the underlying ecosystem that facilitates that circulation. In particular, I focus on the development of services for streaming television over the internet. I examine the circulation paths that either opened up or were foreclosed by companies that have been pivotal in shaping streaming economies: Aereo, Netflix, Twitter, Google, and Amazon. I identify the power brokers of contemporary media distribution, ranging from sectors of legacy television— for instance, broadcast networks, cable companies, and production studios—to a variety of new media and technology industries, including social media, e-commerce, internet search, and artificial intelligence. In addition, I analyze the ways in which these power brokers are reconfiguring content access. I highlight a series of technological, financial, geographic, and regulatory factors that authorize or facilitate access, in order to better understand how contemporary circuits of media distribution are constituted. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 144 3rd International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2017) The Negotiation of Cultural Identity An Analysis of Public Diplomacy Strategies in A Cross-situational Context* He Gong Guangjin Tu School of Journalism and Communication School of Journalism and Communication Xiamen University Renmin University Xiamen, China Beijing, China Abstract—It is widely acknowledged that cultural diversity is (Andersson, Gillespie and Mackay, 2010). a critical aspect of public diplomacy seeking to communicate with international publics. However, little research-based evidence Besides individuals, governments and other organizations exists about what cultural diversity means to practitioners. This also begin their move in social media. For example, the White study examines how the attributions of cultural identity are House has opened an account on both Twitter and Facebook. negotiated in the direct and dialogical (online) conversations The White House now has a stronger presence on Twitter, among the U.S. Embassy and Chinese netizens. It captured and YouTube, Facebook and Vimeo. It even boasts its own iPhone analyzed 1,239 tweets and all the comments that appeared under application (Ng Tze Yong, 2010). the Weibo (Chinese version of Twitter) handle of the U.S. Embassy during the observation period. Within the framework In China, embassies of many countries have adopted of constructionism theory and intercultural public relations, this microblogs to directly speak with Chinese netizens. Countries article asserts that, in a cross-situations where the external including United States, Britain, France, Japan, Denmark, Italy, publics whose cultural identifications differ from those of the Australia, Egypt etc. -

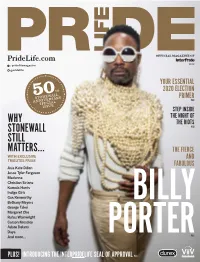

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby.