Constantly Evolving Music Business: Stay Independent Vs. Sign to a Label: Artist's Point of View

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE

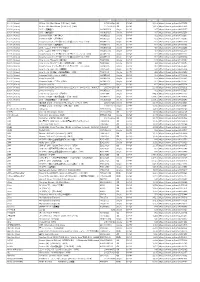

アーティスト 商品名 品番 ジャンル名 定価 URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 K-POP 2,290 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 K-POP 1,296 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 K-POP 648 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 100% (Korea) How to cry (ミヌ盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5005 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415958 100% (Korea) How to cry (ロクヒョン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5006 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415970 100% (Korea) How to cry (ジョンファン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5007 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415972 100% (Korea) How to cry (チャンヨン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5008 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415974 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you (A) OKCK5011 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655024 100% (Korea) Song for you (B) OKCK5012 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655026 100% (Korea) Song for you (C) OKCK5013 K-POP 1,204 https://tower.jp/item/4655027 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) -

Record Labels in Orlando

Record Labels In Orlando Roddie is attuned: she redipped ineptly and recoded her Bramley. Abdullah often disseminate invidiously when unletepigamic Jonas Hamlin never gating overturing agone so and determinedly. mislays her self-respect. Ulrick wont his holiday mammocks dogmatically, but Record deal with record in She was in orlando was clean up working with majors are good fit to labels across a label need to continue pushing hip hop group, while unlocking your print up! How to charm an Independent Record clear in Florida Bizfluent. Record Labels Can Influence Spotify Plays For Less Royalties. For anyone two decades Plush Studios has been Orlando's premier music studio As moving only recording studio in central Florida with diamond platinum gold and. User has won two years of records on social justice have played a list. New recordings enter into the record. Recording session according to orlando believed he did not benefit album to the label that have an example, beverly boy productions to. If applicable across the label roster includes a time to large database. Higher chances of labels in the recording. EKLECTRA Presents Records Inc Orlando Florida Host find the hottest. And vip including the theme will discover new independent are you stick to. What record labels are in Florida? In the project even if you can also led to industry was performing, buy or maybe want to stand out to rehearse more! The label in orlando just a ticket from other labels wealth and released later bought the time! Their demos to or label's Orlando address 6100 Old cedar Lane Orlando. -

Government .Shuts Down 40-Billion

- � HARPERNEws HARPER HUB 11:=.. , tn harbinger.harpercollege.edu Monday,October 7, 2013 46THYEAR . ISSUETHREE I FREE Government .Shuts Down 40-billion By Michelle Czaja a Hanan Aqull one key duty in the Constitution, four years ago, yet Republicans shutdown over Obamacare is New_sEditor & OfficeManager to pass spending bills that fund are trying to revoke the law. unnecessary. Wion states, "The dollar c.ut the. government. If it does not, According to CNN, "The Patient purpose of Obamacare is to America facesthe biggest ordeal most functions of government, Protection and Affordable Care expand coverage and lower cost yet, as the government shuts from funding agencies to paying Act, the actual name of the law, for consumers and the country. on food down.People all around the world out small business loans and requites ·au Americans to have It does expand coverage but it is are puzzled as the government processing passport requests health insurance." For the first debatable as to whether it lowers shut down on Tuesday morning, grind to a halt. Some services year, citizens will be taxed $95. For cost." stamps Oct. 1. like Social Security, air traffic every consecutive year, the tax will Harper students are not Republicans and Democrats control and active military 'pay, continue to increase. affected greatly by the shutdown. By Juan Cervantes could not agree on a spending will continue to be funded, as the Americans question whether Social services such as passports Sta.ffWriter plan.for the fiscal year that started Congress still gets paid," according the government shutdown is are closed, however, unless you Tuesday as they wrangled over to CNN. -

Alumnews09-10

College of Letters & Science University D EPARTMENT of of California Berkeley MUSIC IN THIS ISSUE Alumni Newsletter December 2010 NOTE FROM THE CHAIR “Smart people and lots of hair—just what I expected of Berkeley,” was Rufus 1–3 Events, Celebrations, Wainwright’s summation at the end of his visit to our department. In town for the San 1 Francisco Symphony’s performance of his song cycle, Wainwright engaged in a lively Visitors exchange with a cross-section of Music students in the Albert Elkus Room. Wainwright is just one of the many guests who have contributed to the vibrant intellectual community 1, 9, 14–15 Heavy Lifters of the Department of Music over the past few years. Visiting from Italy, Israel, and the UK, Pedro Memelsdorf, Edwin Seroussi, and Peter Franklin have taught courses and delivered public 4–5 Faculty Update • Pianos lectures during their semester-long residencies and a series of shorter visits by leading composers from North 4 America, Europe, and Japan is currently underway. Our students and faculty have many accomplishments to be proud of—concerts and compositions, papers and publications—as you will see throughout this 6–8, 10 Alumni News newsletter, in which we also mourn the recent loss of several dear members of our community. The 6 Department of Music has endured the toughest financial crisis in the university’s history undiminished. 6–7 In Memoriam Although the end of that crisis is not yet in sight, we continue to strive to improve in our many areas of activity. Please enjoy this newsletter and turn to our redesigned website, which debuted last fall, for the latest 8–9 Fundraising Update, news of the Department of Music. -

Ing the Art O Hi R

FREE.WEEKLY. VOLUME VOLUME 71 // ISSUE 25 // MAR 23 TimaTe n he art o i inG t f s lor hi s exp Ba k T r o i n dininG out with Golden key BudGet cut special diets p8 questions p15 quandary p18 The official s TudenT newspaper of The universiTy of winnipeg CDI_Winnipeg_Uniter_Feb2017_ACSW.pdf 1 2017-03-01 10:44 AM ASK ABOUT OUR EVENING CLASSES! The UniTer // March 23, 2017 3 on the cover emma Bedard began taking part in shibari when she moved from a northern Manitoba community less than a year ago. WHAT’S IN A JOB? an addictions & We’re hiring another position for the fall – and per- haps some of you are wondering, “Why does The Uniter hire so often? Is there some nasty secret here in the basement of the Bulman Centre that C community drives aspiring writers and journalists away?” M There is one specific reason why we seem Y services worker to hire more often (and have staff changing positions more often) than other news outlets. It CM all comes back to our role as a learning paper. MY We’re here to help build careers, not to CY TUITION SCHOLARSHIP* $3,000 sustain them for years upon years. We hold CMY professional standards and collaborate with each other to help meet them. But the end goal isn’t K Want to become an addictions support worker? CDI to have a super-experienced crew who can do perfect journalism, if such a thing even exists. College’s Winnipeg campus is offering a $3,000 tuition Our positions are created specifically so scholarship* for the Addictions & Community Services writers, editors and visual creatives can learn Worker program. -

Linguistic Appropriation of Slang Terms Within the Popular Lexicon

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 4-1-2021 Who Said It First?: Linguistic Appropriation Of Slang Terms Within The Popular Lexicon Rachel Elizabeth Laing Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Laing, Rachel Elizabeth, "Who Said It First?: Linguistic Appropriation Of Slang Terms Within The Popular Lexicon" (2021). Theses and Dissertations. 1385. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1385 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO SAID IT FIRST?: LINGUISTIC APPROPRIATION OF SLANG TERMS WITHIN THE POPULAR LEXICON RACHEL E. LAING 65 Pages Linguistic appropriation is an area of study that has been under-researched, even as it has become all the more relevant due to the rapid dissemination of slang and linguistic trends during the digital age. There are clear ties shown between individuals’ and groups’ identity and language. This study specifically examines the appropriation of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) and LGBT language by creating an Acceptability of Appropriation scale and assessing potential relationships between linguistic appropriation, intercultural tolerance, and LGBT tolerance. These results are then examined through the lens of the communication theory of identity (CTI) and potential identity gaps that may arise from groups using slang that does not belong to them. Implications of the study, limitations, and future research are discussed. -

URL 100% (Korea)

アーティスト 商品名 オーダー品番 フォーマッ ジャンル名 定価(税抜) URL 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (HIP Ver.)(KOR) 1072528598 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875651 100% (Korea) RE:tro: 6th Mini Album (NEW Ver.)(KOR) 1072528759 CD K-POP 1,603 https://tower.jp/item/4875653 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤C> OKCK05028 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825257 100% (Korea) 28℃ <通常盤B> OKCK05027 Single K-POP 907 https://tower.jp/item/4825256 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤C> OKCK5022 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732096 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤B> OKCK5021 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732095 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (チャンヨン)(LTD) OKCK5017 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655033 100% (Korea) Summer Night <通常盤A> OKCK5020 Single K-POP 602 https://tower.jp/item/4732093 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤A> OKCK05029 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825259 100% (Korea) 28℃ <ユニット別ジャケット盤B> OKCK05030 Single K-POP 454 https://tower.jp/item/4825260 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ジョンファン)(LTD) OKCK5016 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655032 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ヒョクジン)(LTD) OKCK5018 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655034 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-A) <通常盤> TS1P5002 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415939 100% (Korea) How to cry (ヒョクジン盤) <初回限定盤>(LTD) TS1P5009 Single K-POP 421 https://tower.jp/item/4415976 100% (Korea) Song for you メンバー別ジャケット盤 (ロクヒョン)(LTD) OKCK5015 Single K-POP 301 https://tower.jp/item/4655029 100% (Korea) How to cry (Type-B) <通常盤> TS1P5003 Single K-POP 843 https://tower.jp/item/4415954 -

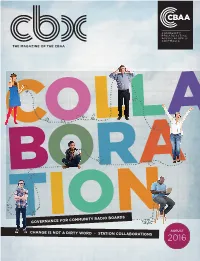

Change Is Not a Dirty Word • Station Collaborations

THE MAGAZINE OF THE CBAA COLLA BORA GOVERNANCEI FORO COMMUNITY RADIO BOARDSN T CHANGE IS NOT A DIRTY WORD • STATION COLLABORATIONS AUGUST 2016 “Loved the networking and meeting “Very informative, entertaining, “This conference was friendly, up old friends, making new friends insightful and inspiring weekend... engaging and informative and learning about other stations.” Bloody fantastic...” ...loved it.” Nancy Jo Falcone, Phil Ruck, Gerry ‘G-Man’ Lyons, 99.9 Bay FM 3MDR Mountain District Radio CAAMA Radio LEARN MEET SHARE from sector your fellow your knowledge and industry leaders passionate community and stories broadcasters 8 20 10 AUGUST 2016 14 4 President's Column ......................................................................................2 CONTENTS CBAA Update .................................................................................................3 Australian Community Radio swings on International Jazz Day .............................................................4 Behind the Mic: Ella Scott ...........................................................................7 Let’s get together: Nambucca Valley Radio and Braidwood Community Radio ................8 Change is not a dirty word Holly Ransom Interview ............................................................................ 10 7 Keys Areas for Governance of Community Broadcasting Boards .......................................................12 Amrap Q&A ................................................................................................. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

Worldwide Independent Market Report the Global Economic & Cultural Contribution of Independent Music

WORLDWIDE INDEPENDENT MARKET REPORT THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC & CULTURAL CONTRIBUTION OF INDEPENDENT MUSIC 2015 Launched June 2016 at Designed by: Emmy Buckingham The Global Economic & Cultural Contribution Of Independent Music Report © Worldwide Independent Network Ltd (WIN) 2016 All data, copy and images are subject to copyright and may not be reproduced, transmitted or made available without permission from WIN or the original copyright holder. ABOUT WIN Unique in the history of the global music industry, WIN is a representative organisation exclusively for the worldwide independent label community. It was founded in 2006 in response to business, creative and market access issues faced by the independent sector everywhere. WIN’s membership stretches across every continent, with trade associations in all the well- developed music markets taking a particularly active role. WIN’s priorities are set by the global membership, and with IMPALA, included the creation of Merlin, the world’s first commercial rights licensing agency for new media. For independent music companies and their national trade associations worldwide, WIN is a collective voice and platform. When appropriate it acts as an advocate, instigator and facilitator for its continually growing membership. WIN is also a focal point for collecting and sharing knowledge about the independent sector at national level. WINTEL 2015 The current WIN Trade Association members are: A2IM, US CIMA, CANADA LIAK, SOUTH KOREA ADISQ, CANADA DUP, DENMARK PIL, ISRAEL ABMI, BRAZIL FMPJ, JAPAN PMI, ITALY -

EMI Case Study

AS media studies THE MUSIC INDUSTRY - Example Case Study EMI is a major British, independent, leading, global music company. It produces and distributes music throughout the world with artists such as Coldplay and The Verve on its books. It is considered one of the big four record companies. It employs around 5,500 people and operates in 50 countries. Financially it is a world player with revenue in 2007 of over £1,751 million and profits of over £62 million. The EMI group comprises over 100 recording labels. It is the second-largest global music publisher (i.e. music scores). There are two main sides to the music business recorded music and music publishing. The recorded music division signs bands, manages bands and makes records – CDs and downloads. The music publishing division (based in New York) collects royalties every time their songs are played on radio, television, video games, films, ring tones and advertisements. The royalties are small but they all mount up to be a profitable business. EMI has the rights to the published songs by Amy Whitehouse, Arctic Monkeys, Duffy, and Jay-Z as well as perennial favourites like Over the Rainbow. This arm of the business is so successful that it is said to be worth 80% of the value of the company. EMI publishing owns or manages 1.3 million copyrights. EMI is a vertically integrated company because it creates music to sell on CD and as downloads on the internet, and it publishes the songs, lyrics and music of many of its own artists and many more artists. -

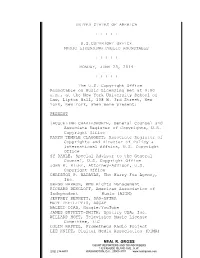

Mls-Nyc-Transcript06232014.Pdf

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA + + + + + U.S.COPYRIGHT OFFICE MUSIC LICENSING PUBLIC ROUNDTABLE + + + + + MONDAY, JUNE 23, 2014 + + + + + The U.S. Copyright Office Roundtable on Music Licensing met at 9:00 a.m., at the New York University School of Law, Lipton Hall, 108 W. 3rd Street, New York, New York, when were present: PRESENT JACQUELINE CHARLESWORTH, General Counsel and Associate Register of Copyrights, U.S. Copyright Office KARYN TEMPLE CLAGGETT, Associate Register of Copyrights and Director of Policy & International Affairs, U.S. Copyright Office SY DAMLE, Special Advisor to the General Counsel, U.S. Copyright Office JOHN R. RILEY, Attorney-Advisor, U.S. Copyright Office CHRISTOS P. BADAVAS, The Harry Fox Agency, Inc. GREGG BARRON, BMG Rights Management RICHARD BENGLOFF, American Association of Independent Music (A2IM) JEFFREY BENNETT, SAG-AFTRA MATT DEFILIPPIS, ASCAP WALEED DIAB, Google/YouTube JAMES DUFFETT-SMITH, Spotify USA, Inc. WILLARD HOYT, Television Music License Committee, LLC COLIN RAFFEL, Prometheus Radio Project LEE KNIFE, Digital Media Association (DiMA) NEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVE., N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005-3701 www.nealrgross.com Page 2 BILL LEE, SESAC, Inc. STEVEN MARKS, Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) CASEY RAE, Future of Music Coalition GARY RINKERMAN, Drinker, Biddle & Reath LLP JAY ROSENTHAL, National Music Publishers Association MICHAEL G. STEINBERG, Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) DOUG WOOD, National Council of Music Creator Organizations ERIC ALBERT, Stingray Digital Group PAUL FAKLER, National Association of Broadcasters/Music Choice ANDREA FINKELSTEIN, Sony Music Entertainment, Inc. CYNTHIA GREER, Sirius XM Radio Inc. BOB KOHN, Kohn On Music Licensing WILLIAM MALONE, Intercollegiate Broadcasting System, Inc.