The 2014 Spring AMEDD Historian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

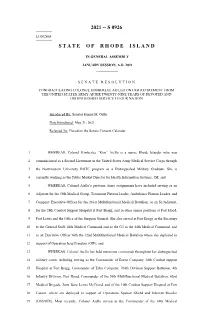

S 0926 State of Rhode Island

2021 -- S 0926 ======== LC002865 ======== STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2021 ____________ S E N A T E R E S O L U T I O N CONGRATULATING COLONEL KIMBERLEE AIELLO ON HER RETIREMENT FROM THE UNITED STATES ARMY AFTER TWENTY-NINE YEARS OF DEVOTED AND DISTINGUISHED SERVICE TO OUR NATION Introduced By: Senator Hanna M. Gallo Date Introduced: May 21, 2021 Referred To: Placed on the Senate Consent Calendar 1 WHEREAS, Colonel Kimberlee “Kim” Aiello is a native Rhode Islander who was 2 commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the United States Army Medical Service Corps through 3 the Northeastern University ROTC program as a Distinguished Military Graduate. She is 4 currently working as the Public Market Director for Health Information Systems, 3M; and 5 WHEREAS, Colonel Aiello’s previous Army assignments have included serving as an 6 Adjutant for the 55th Medical Group, Treatment Platoon Leader, Ambulance Platoon Leader, and 7 Company Executive Officer for the 261st Multifunctional Medical Battalion, as an S1/Adjutant, 8 for the 28th Combat Support Hospital at Fort Bragg, and in other senior positions at Fort Hood, 9 Fort Lewis and the Office of the Surgeon General. She also served at Fort Bragg as the Secretary 10 to the General Staff, 44th Medical Command and as the G3 to the 44th Medical Command, and 11 as an Executive Officer with the 32nd Multifunctional Medical Battalion where she deployed in 12 support of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); and 13 WHEREAS, Colonel Aiello has held numerous commands throughout her distinguished 14 military career including serving as the Commander of Bravo Company, 28th Combat support 15 Hospital at Fort Bragg, Commander of Echo Company, 704th Division Support Battalion, 4th 16 Infantry Division, Fort Hood, Commander of the 56th Multifunctional Medical Battalion, 62nd 17 Medical Brigade, Joint Base Lewis McChord, and of the 10th Combat Support Hospital at Fort 18 Carson, where she deployed in support of Operations Spartan Shield and Inherent Resolve 19 (OSS/OIR). -

The United States Army Medical Department

THE UNITED STATES ARMY MEDICAL DEPARTMENT OURNAL THE MULTIDISCIPLINARY ASPECTS OF PUBLIC HEALTH January-June 2018 FirstJ Record of Aedes (Stegomyia) malayensis Colless (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Based on Morphological Diagnosis and Molecular Analysis 1 Maysa T. Motoki, PhD; Elliott F. Miot, MS; Leopoldo M. Rueda, PhD; et al Mosquito Surveillance Conducted by US Military Personnel in the Aftermath of the Nuclear Explosion at Nagasaki, Japan, 1945 8 David B. Pecor, BS; Desmond H. Foley, PhD; Alexander Potter Georgia’s Collaborative Approach to Expanding Mosquito Surveillance in Response to Zika Virus: Year Two 14 Thuy-Vi Nguyen, PhD, MPH; Rosmarie Kelly, PhD, MPH; et al An Excel Spreadsheet Tool for Exploring the Seasonality of Aedes Vector Hazard for User-Specified Administrative Regions of Brazil 22 Desmond H. Foley, PhD; David B. Pecor, BS Surveillance for Scrub Typhus, Rickettsial Diseases, and Leptospirosis in US and Multinational Military Training Exercise Cobra Gold Sites in Thailand 29 Piyada Linsuwanon, PhD; Panadda Krairojananan, PhD; COL Wuttikon Rodkvamtook, PhD, RTA; et al Risk Assessment Mapping for Zoonoses, Bioagent Pathogens, and Vectors at Edgewood Area, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland 40 Thomas M. Kollars, Jr, PhD; Jason W. Kollars Optimizing Mission-Specific Medical Threat Readiness and Preventive Medicine for Service Members 49 COL Caroline A. Toffoli, VC, USAR Public Health Response to Imported Mumps Cases–Fort Campbell, Kentucky, 2018 55 LTC John W. Downs, MC, USA Developing Medical Surveillance Examination Guidance for New Occupational Hazards: The IMX-101 Experience 60 W. Scott Monks, MPAS, PA-C Missed Opportunities in Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Uptake Among US Air Force Recruits, 2009-2015 67 COL Paul O. -

Vincent Codispoti, Md

VINCENT CODISPOTI, M.D. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Interventional Pain Management ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ CURRENT POSITION Associate Physician, Orthopedic Associates of Hartford Interventional Physiatrist; August 2014-present EDUCATION & TRAINING Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Anesthesia- Pain Management Fellowship, 2013- 2014 Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation Resident, 2006- 2009 Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Transitional Intern, 2005-2006 New York University School of Medicine, M.D., 2001-2005 Vassar College, B.A., with Honors, Economics, 1997-2001 BOARD CERTIFICATION American Board of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation American Board of Electrodiagnostic Medicine Pain Medicine, Board Eligible September 2014 ACADEMIC & PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Staff Physiatrist, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 2011-2013 Staff Physiatrist, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, 2009-2011 Assistant Professor of Neurology, Uniformed Services University of Health Science, 2009-2013 LEADERSHIP POSITIONS Associate Residency Program Director, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 2012-2013 Director of Electrodiagnostic Medicine, Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, 2011-2013 Director of Undergraduate Medical Education, -

Fm 8-10-14 Employment of the Combat Support Hospital Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures

FM 8-10-14 FIELD MANUAL HEADQUARTERS No. 8-10-14 DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY Washington, DC, 29 December 1994 FM 8-10-14 EMPLOYMENT OF THE COMBAT SUPPORT HOSPITAL TACTICS, TECHNIQUES, AND PROCEDURES Table of Contents PREFACE CHAPTER 1 - HOSPITALIZATION SYSTEM IN A THEATER OF OPERATIONS 1-1. Combat Health Support in a Theater of Operations 1-2. Echelons of Combat Health Support 1-3. Theater Hospital System CHAPTER 2 - THE COMBAT SUPPORT HOSPITAL 2-1. Mission and Allocation 2-2. Assignment and Capabilities 2-3. Hospital Support Requirements 2-4. Hospital Organization and Functions 2-5. The Hospital Unit, Base 2-6. The Hospital Unit, Surgical CHAPTER 3 - COMMAND, CONTROL, AND COMMUNICATIONS OF THE COMBAT SUPPORT HOSPITAL DODDOA-004215 ACLU-RDI 320 p.1 3-1. Command and Control 3-2. Communications CHAPTER 4 - DEPLOYMENT AND EMPLOYMENT OF THE COMBAT SUPPORT HOSPITAL 4-1. Threat 4-2. Planning Combat Health Support Operations 4-3. Mobilization 4-4. Deployment 4-5. Employment 4-6. Hospital Displacement 4-7. Emergency Displacement 4-8. Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Operations APPENDIX A - TACTICAL STANDING OPERATING PROCEDURE FOR HOSPITAL OPERATIONS A-1. Tactical Standing Operating Procedure A-2. Purpose of the Tactical Standing Operating Procedure A-3. Format for the Tactical Standing Operating Procedure A-4. Sample Tactical Standing Operating Procedure (Sections) A-5. Sample Tactical Standing Operating Procedure (Annexes) APPENDIX B - HOSPITAL PLANNING FACTORS B-1. General B-2. Personnel and Equipment Deployable Planning Factors B-3. Hospital Operational Space Requirements B-4. Logistics Planning Factors (Class 1, II, III, IV, VI, VIII) APPENDIX C - FIELD WASTE Section I - Overview DODDOA-004216 ACLU-RDI 320 p.2 • C-1. -

Army Medical Specialist Corps in Vietnam Colonel Ann M

Army Medical Specialist Corps in Vietnam Colonel Ann M. Ritchie Hartwick Background Medical Groups which were established and dissolved as medical needs dictated throughout Though American military advisers had been the war. On 1 March 1970, Army medical dual in French Indochina since World War II, staff functions were reduced with the and the American Advisory Group with 128 establishment of the U.S. Army Medical positions was assigned to Saigon in 1950, the Command, Vietnam (Provisional). Army Surgeon General did not establish a hospital in Vietnam until 1962 (the Eighth The 68th Medical Group, operational on 18 Field Hospital at Nha Trang) to support March 1966, was located in Long Binh and American personnel in country. Between 1964 supported the medical mission in the III and IV and 1969 the number of American military combat tactical zones (CTZs). The 55th personnel in Vietnam increased from 23,000 Medical Group, operational in June 1966, to 550,000 as American combat units were supported the medical mission in the northern deployed to replace advisory personnel in II CTZ and was located at Qui Nhon. The 43d support of military operations. Medical Group, operational in November 1965, supported the medical mission for Between 1964 and 1973 the Army Surgeon southern II CTZ and was located at Nha Trang. General deployed 23 additional hospitals And, in October 1967, the 67th Medical established as fixed medical installations with Group, located at Da Nang, assumed area support missions. These included surgical, medical support responsibility for ICTZ. evacuation, and field hospitals and a 3,000 bed convalescent center, supported by a centralized blood bank, medical logistical support Army Physical Therapists installations, six medical laboratories, and The first member of the Army Medical multiple air ambulance ("Dust Off") units. -

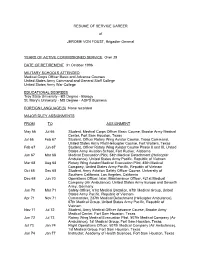

Cofs, USA MEDCOM

RESUME OF SERVICE CAREER of JEROME VON FOUST, Brigadier General YEARS OF ACTIVE COMMISSIONED SERVICE Over 29 DATE OF RETIREMENT 31 October 1996 MILITARY SCHOOLS ATTENDED Medical Corps Officer Basic and Advance Courses United States Army Command and General Staff College United States Army War College EDUCATIONAL DEGREES Troy State University - BS Degree - Biology St. Mary's University - MS Degree - ADPS Business FOREIGN LANGUAGE(S) None recorded MAJOR DUTY ASSIGNMENTS FROM TO ASSIGNMENT May 66 Jul 66 Student, Medical Corps Officer Basic Course, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, Texas Jul 66 Feb 67 Student, Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Course, Troop Command, United States Army Pilot/Helicopter Course, Fort Wolters, Texas Feb 67 Jun 67 Student, Officer Rotary Wing Aviator Course Phase II and III, United States Army Aviation School, Fort Rucker, Alabama Jun 67 Mar 68 Medical Evacuation Pilot, 54th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance), United States Army Pacific, Republic of Vietnam Mar 68 Aug 68 Rotary Wing Aviator/Medical Evacuation Pilot, 45th Medical Company, United States Army Pacific, Republic of Vietnam Oct 68 Dec 68 Student, Army Aviation Safety Officer Course, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California Dec 68 Jun 70 Operations Officer, later, Maintenance Officer, 421st Medical Company (Air Ambulance), United States Army Europe and Seventh Army, Germany Jun 70 Mar 71 Safety Officer, 61st Medical Battalion, 67th Medical Group, United States Army Pacific, Republic of Vietnam Apr 71 Nov 71 Commander, 237th -

A Worldwide Publication Telling the Army Medicine Story ARMY MEDICINE MERCURY CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS

Volume 42, No. 1 A worldwide publication telling the Army Medicine Story ARMY MEDICINE MERCURY CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS FEATURE 2 | ARMYMEDICINE.MIL ARMY MEDICINE MERCURY US ARMY MEDICAL COMMAND ARMY MEDICINE PRIORITIES Commander COMBAT CASUALTY CARE Lt. Gen. Patricia D. Horoho Army Medicine personnel, services, and doctrine that save Service members’ and DOD Civilians’ lives and maintain their health in all operational environments. Director of Communications Col. Jerome L. Buller READINESS AND HEALTH OF THE FORCE Chief, MEDCOM Public Army Medicine personnel and services that maintain, restore, and improve the Affairs Officer deployability, resiliency, and performance of Service members. Jaime Cavazos Editor READY & DEPLOYABLE MEDICAL FORCE Dr. Valecia L. Dunbar, D.M. AMEDD personnel who are professionally developed and resilient, and with their units, are responsive in providing the highest level of healthcare in all operational environments. Graphic Designers Jennifer Donnelly Rebecca Westfall HEALTH OF FAMILIES AND RETIREES Army Medicine personnel and services that optimize the health and resiliency of Families and Retirees. The MERCURY is an authorized publication for members of the U.S. Army Medical Department, published under the authority CONNECT WITH ARMY MEDICINE of AR 360-1. Contents are not necessarily official views of, or endorsed by, the U.S. CLICK ON A LINK BELOW AND JOIN THE CONVERSATION Government, Department of Defense, Department of the Army, or this command. The MERCURY is published FACEBOOK monthly by the Directorate of Communications, U.S. Army FLICKR Medical Command, 2748 Worth Road Ste 11, Fort Sam Houston, TX 78234-6011. Questions, comments or submissions for the MERCURY should be directed to the editor at 210-221-6722 (DSN 471-7), or by email; TWITTER The deadline is 25 days before the month of publication. -

USAMRDC U.S. Medical Research and Development Command

U.S. Medical Research and USAMRDC Development Command Brigadier General Anthony (Tony) McQueen Commanding General U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command and Fort Detrick Brigadier General McQueen is a native of Texas and a graduate of Sam Houston State University where he was commissioned as an ROTC Distinguished Military Graduate in 1991. Brigadier General McQueen most recently served as the Deputy Chief of Staff, G-3/5/7 United States Army Medical Command and was detailed to Operation Warp Speed from May 2020 - May 2021. He has commanded at every level from company through brigade. He most recently commanded Blanchfield Army Community Hospital, United States Army Medical Activity, Fort Campbell, Kentucky from June 2017 to June 2019 and the 402d Army Field Support Brigade, Fort Shafter, Hawaii from August 2015 to June 2017. He served two Operation Iraqi Freedom combat tours and two tours in the Republic of Korea. He has served with the 2nd Infantry Division, the 25th Infantry Division, 4th Infantry Division, and the 1st Cavalry Division. He has also held key leadership positions at both the Medical Brigade and Brigade Combat Team levels, Division Staff, U.S. Army Medical Center of Excellence, and the Office of the Surgeon General. Brigadier General McQueen is a graduate of the Army Medical Department Officer Basic Course; he has also completed the Combined Logistics Officer Advanced Course, the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and the National War College. He holds a Master of Science in National Security Strategy, and a Master of Arts in Health Services Management. -

The Crucible of Military Medical Ethics

Medical Ethics on the Battlefield: The Crucible of Military Medical Ethics MILITARY MEDICAL ETHICS VOLUME 2 SECTION IV: MEDICAL ETHICS IN THE MILITARY Section Editor: THOMAS E. BEAM, MD Formerly Director, Borden Institute Formerly, Medical Ethics Consultant to The Surgeon General, United States Army Robert Benney Shock Tent circa World War II Art: Courtesy of Army Art Collection, US Army Center of Military History, Washington, DC. 367 Military Medical Ethics, Volume 2 368 Medical Ethics on the Battlefield: The Crucible of Military Medical Ethics Chapter 13 MEDICAL ETHICS ON THE BATTLEFIELD: THE CRUCIBLE OF MILITARY MEDICAL ETHICS THOMAS E. BEAM, MD* INTRODUCTION RETURN TO DUTY CONSIDERATIONS IN A THEATER OF OPERATIONS Getting Minimally Wounded Soldiers Back to Duty Combat Stress Disorder “Preserve the Fighting Strength” Informed Consent Beneficence for the Soldier in Combat Enforced Treatment for Individual Soldiers BATTLEFIELD TRIAGE The Concept of Triage Establishing and Maintaining Prioritization of Treatment Models of Triage Examining the Extreme Conditions Model EUTHANASIA ON THE BATTLEFIELD Understanding the Dynamics of the Battlefield: The Swann Scenario A Brief History of Battlefield Euthanasia A Civilian Example From a “Battlefield” Setting Available Courses of Action: The Swann Scenario Ethical Analysis of Options PARTICIPATION IN INTERROGATION OF PRISONERS OF WAR Restrictions Imposed by the Geneva Conventions “Moral Distancing” Developing and Participating in Torture Battlefield Cases of Physician Participation in Torture CONCLUSION *Colonel (Retired), Medical Corps, United States Army; formerly, Director, Borden Institute, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC 20307-5001 and Medical Ethics Consultant to The Surgeon General, United States Army; formerly, Director, Operating Room, 28th Combat Support Hospital (deployed to Saudi Arabia and Iraq, Persian Gulf War) 369 Military Medical Ethics, Volume 2 Robert Benney The Battle of the Caves Anzio, 1944 The painting depicts battlefield medicine in the Mediterranean theater in World War II. -

20190529 Medical Service Corps (V3) DA PAM 600-4.Pdf

Medical Service Corps 1. Description of the Medical Service Corps The Medical Service Corps (MSC) is comprised of a wide diversity of health care administrative and scientific specialties ranging from the management and support of the Army’s health services system to direct patient care. IAW 10 USC 3068, the leadership within the MSC consists of the Corps Chief and four Assistant Corps Chiefs who also function as the chiefs of the four medical functional areas (MFAs): Administrative Health Services, Medical Allied Sciences, Preventive Medicine Sciences, and Behavioral Health Sciences. A fifth Assistant Corps Chief functions as a Reserve and National Guard Advisor. The MSC consists of four MFAs, four separate areas of concentration (AOC), and one military occupational specialty (MOS). The Assistant Chiefs provide career direction to their respective MFA/AOC/MOS as well as recommend policies to the Corps Chief. In addition to the Assistant Chiefs, each AOC (and certain skill identifiers) has a specific consultant that advises the Corps Chief and Assistant Chiefs. The operational element which implements Corps policies concerning the career development of Regular Army MSC officers is the Medical Services Branch at HRC, which coordinates military and civilian schooling, assignments, skill classification, career management assistance, and other personnel management actions. A primary objective of this branch is to assist each officer to attain career goals by providing appropriate assignments and ensuring objective consideration for educational opportunities. The MSC consists of four MFAs that have 22 AOCs. All MSC officers (except warrant officers) will be awarded one of the 22 MSC AOCs: 67E, 67F, 67G, 67J, 70A, 70B, 70C, 70D, 70E, 70F, 70H, 70K, 71A, 71B, 71E, 71F, 72A, 72B, 72C, 72D, 73A, and 73B. -

A Worldwide Publication Telling the Army Medicine Story ARMY MEDICINE MERCURY CONTENTS

Volume 42, No. 9 JUNE 2015 A worldwide publication telling the Army Medicine Story ARMY MEDICINE MERCURY CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 03 04 TSG Speaks! FEATURE 18 05 15 Around Army Medicine 06 AMEDD Global 25 Recognitions 12 13 Men’s Health Month 14 Performance Triad 16 It’s All About Health. 2 MERCURY | ARMYMEDICINE.MIL ARMY MEDICINE MERCURY US ARMY MEDICAL COMMAND ARMY MEDICINE PRIORITIES Commander Lt. Gen. Patricia D. Horoho COMBAT CASUALTY CARE Army Medicine personnel, services, and doctrine that save Service members’ and DOD Director of Communications Civilians’ lives and maintain their health in all operational environments. Col. John Via Chief, MEDCOM Public READINESS AND HEALTH OF THE FORCE Affairs Officer Army Medicine personnel and services that maintain, restore, and improve the Kirk Frady deployability, resiliency, and performance of Service members. Editor Dr. Valecia L. Dunbar, D.M. READY & DEPLOYABLE MEDICAL FORCE AMEDD personnel who are professionally developed and resilient, and with their units, Graphic Designer are responsive in providing the highest level of healthcare in all operational environments. Jennifer Donnelly HEALTH OF FAMILIES AND RETIREES The MERCURY is an Army Medicine personnel and services that optimize the health and resiliency of Families authorized publication and Retirees. for members of the U.S. Army Medical Department, published under the authority of AR 360-1. Contents are not necessarily official views CONNECT WITH ARMY MEDICINE of, or endorsed by, the U.S. Government, Department of Defense, Department of the CLICK ON A LINK BELOW AND JOIN THE CONVERSATION Army, or this command. The MERCURY is published monthly by the Directorate of FACEBOOK FLICKR Communications, U.S. -

Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare, Front Matter

MEDICAL ASPECTS OF CHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL WARFARE i The Coat of Arms 1818 Medical Department of the Army A 1976 etching by Vassil Ekimov of an original color print that appeared in The Military Surgeon, Vol XLI, No 2, 1917 ii The first line of medical defense in wartime is the combat medic. Although in ancient times medics carried the caduceus into battle to signify the neutral, humanitarian nature of their tasks, they have never been immune to the perils of war. They have made the highest sacrifices to save the lives of others, and their dedication to the wounded soldier is the foundation of military medical care. iii Textbook of Military Medicine Published by the Office of The Surgeon General Department of the Army, United States of America Editor in Chief Brigadier General Russ Zajtchuk, MC, U.S. Army Director, Borden Institute Commanding General U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Professor of Surgery F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Bethesda, Maryland Managing Editor Ronald F. Bellamy, M.D. Colonel, MC, U.S. Army (Retired) Borden Institute Associate Professor of Military Medicine Associate Professor of Surgery F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Bethesda, Maryland iv The TMM Series Part I. Warfare, Weaponry, and the Casualty Medical Consequences of Nuclear Warfare (1989) Conventional Warfare: Ballistic, Blast, and Burn Injuries (1991) Military Psychiatry: Preparing in Peace for War (1994) War Psychiatry (1995) Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare (1997) Military Medical Ethics Part II. Principles of Medical Command and Support Military Medicine in Peace and War Part III.