Identity Formation in the Thirteen American Colonies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

Minting America: Coinage and the Contestation of American Identity, 1775-1800

ABSTRACT MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 by James Patrick Ambuske “Minting America” investigates the ideological and culture links between American identity and national coinage in the wake of the American Revolution. In the Confederation period and in the Early Republic, Americans contested the creation of a national mint to produce coins. The catastrophic failure of the paper money issued by the Continental Congress during the War for Independence inspired an ideological debate in which Americans considered the broader implications of a national coinage. More than a means to conduct commerce, many citizens of the new nation saw coins as tangible representations of sovereignty and as a mechanism to convey the principles of the Revolution to future generations. They contested the physical symbolism as well as the rhetorical iconology of these early national coins. Debating the stories that coinage told helped Americans in this period shape the contours of a national identity. MINTING AMERICA: COINAGE AND THE CONTESTATION OF AMERICAN IDENTITY, 1775-1800 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by James Patrick Ambuske Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2006 Advisor______________________ Andrew Cayton Reader_______________________ Carla Pestana Reader_______________________ Daniel Cobb Table of Contents Introduction: Coining Stories………………………………………....1 Chapter 1: “Ever to turn brown paper -

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

The Common Sense Media Use by Kids Census: Age Zero to Eight

2017 THE COMMON SENSE MEDIA USE BY KIDS CENSUS: AGE ZERO TO EIGHT Common Sense is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization dedicated to improving the lives of kids, families, and educators by providing the trustworthy information, education, and independent voice they need to thrive in a world of media and technology. Our independent research is designed to provide parents, educators, health organizations, and policymakers with reliable, independent data on children’s use of media and technology and the impact it has on their physical, emotional, social, and intellectual development. For more information, visit www.commonsense.org/research. Common Sense is grateful for the generous support and underwriting that funded this research report. The Morgan Peter and The David and Lucile Family Foundation Helen Bing Packard Foundation Carnegie Corporation of New York The Grable Foundation Eva and Bill Price John H.N. Fisher and Jennifer Caldwell EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Opening Letter 4 Essays 6 Jenny Radesky: Taking Advantage of Real Opportunities to Help Families Overwhelmed by Technology . 6 Michael H. Levine: M Is for Mobile . 6 Julián Castro: A Narrowing but Still Troubling Divide . 8 At a Glance: Evolution of Kids’ Media Use 2011–2017 9 Introduction 11 Methodology 12 Survey Sample . 12 Media Definitions . 12 Demographic Definitions. 13 Presentation of Data in the Text . 13 Key Findings 15 Conclusion 29 Board of Directors 30 Board of Advisors 30 To access the full research report, visit www commonsense org/zero-to-eight-census At Common Sense, our mission has always been to help families navigate the vast and ever-changing landscape of media and technology. -

816 0008G.Pdf

8 Meanwhile, the Second Continental Congress was moving inexorably towards a clean break from England. On June 7, 1776, fiery Henry Lee of Virginia moved that the united colonies should declare their independence. Lee’s resolution was formally adopted on July 2. Congress then appointed a committee to prepare an appropriate statement. A rupture of this nature called for a formal explanation to justify such action, to rally resistance in the colonies, and to win support from foreign nations. Thomas Jefferson was called upon as one contemporary described it to “advertise Mr. Lee’s resolution.” Jefferson rose to the occasion and gave his appeal a universal flavor by invoking the natural rights of humankind. Every attempt was made to make it clear that George III was the villain and not the British people. Jefferson was a product of the Enlightenment Period, and he borrowed extensively from Rousseau, Locke, Voltaire, Montesquieu, and others. Jefferson delivered a withering blast at British tyranny and was not above taking certain liberties with historical truth. Some critics viewed his declaration as “the world’s greatest editorial.” The Declaration of Independence had a universal impact and was a “shout heard round the world.” It became the source of countless revolutionary movements against arbitrary power. VIDEO OBJECTIVES The following objectives are designed to assist the viewer in identifying the most significant aspects of the video segment of this lesson. You should take succinct notes while viewing the video. 1. Assess the significance of the Second Continental Congress. 2. Analyze the importance of Thomas Paine and his Common Sense and his American Crisis papers. -

Thomas Paine's Influential Rhetoric in Common Sense

Revolutionary Persuasion: Thomas Paine’s Influential Rhetoric in Common Sense On January 10, 1776, an unknown English immigrant drastically altered the course of human events by publishing what has been referred to as the most influential pamphlet in American history. This man was Thomas Paine, and his pamphlet was titled Common Sense - two words which to this very day resonate as synonymous with American independence and freedom. Paine’s influential writing in Common Sense made an immediate impact on the minds and hearts of thousands of colonists throughout the densely populated eastern seaboard of North America, calling for an end to tyrannical British rule and for the subsequent foundation of an independent, egalitarian republic. Paine’s “hardnosed political logic demanded the creation of an American nation” (Rhetoric, np), and through his persuasive discourse he achieved just that. Paine’s knowledge and use of rhetorical skill was a main reason for the groundbreaking, widespread success of Common Sense, the magnitude of which, many would argue, has yet to be matched. Rhetoric is the art or science of persuasion and the ability to use language effectively. This paper will provide an in-depth analysis of Paine’s rhetoric in Common Sense by examining factors such as the historical time period, communicator attributes, and audience psychology, and will deliver a thorough application of contemporary modes of persuasive study to the document’s core ideological messages. To Paine, the cause of America was the cause of all mankind (Paine, 3), and for that matter he will be forever known as the father of the American Revolution. -

7.2 and 7.3 Notes Common Sense •Common Sense- Pamphlet Written

7.2 and 7.3 Notes Common Sense •Common Sense- pamphlet written by Thomas Paine •Argued for breaking away from GB •Sold 500,000 copies across the colonies •Written for the common man •Said people, not kings/queens should make the laws •Helped to gain support for independence Declaring Independence •June 1776, Second Continental Congress created a committee to write the Declaration of Independence –John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, Roger Sherman were all committee members –Thomas Jefferson was the main author Declaration of Independence •Three main ideas –All men possess unalienable rights •Life, liberty, pursuit of happiness –King George III violated the colonists’ rights •Passing unfair laws, interfering with colonial self-gov’t •Taxing colonies w/out their consent –Colonies had the right to break away from GB •Rulers should protect the rights of their citizens –July 4th, 1776 Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence Patriots Vs. Loyalists •Patriots-colonists who fought for independence •Loyalists- colonists who remained loyal to GB –Also called Tories •Loyalists became targets of abuse by Patriots •100,000 loyalists fled to Canada during the revolution Reactions to the Declaration •The Declaration did not give everyone freedom •Some were upset that the wording of the Declaration of Independence “all men are created equal” did not mention women –Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams was a proponent for women’s recognition •The Declaration also did not recognize enslaved African Americans -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

PERHAPS the Sentiments Contained in the Following Pages Are Not Yet Sufficiently Fashionable to Procure Them General Favor

LESSON: THOMAS PAINE, COMMON SENSE, 1776 FULL TEXT “for God’s sake, let us come New York Public Library to a final separation” Thomas Paine COMMON SENSE *January 1776 Presented here is the full text of Common Sense from the third edition (published a month after the initial pamphlet), plus the edition Appendix, now considered an integral part of the pamphlet’s impact. INTRODUCTION 1 PERHAPS the sentiments contained in the following pages are not yet sufficiently fashionable to procure them general favor. A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong gives it a superficial appearance of being right, and raises at first a formidable outcry in defense of custom. But the tumult soon subsides. Time makes more converts than reason. 2 As a long and violent abuse of power is generally the Means of calling the right of it in question (and in Matters too Thomas Paine which might never have been thought of, had not the American Antiquarian Society Sufferers been aggravated into the inquiry), and as the King of England hath undertaken in his own Right to support the Parliament in what he calls Theirs, and as the good people of this country are grievously oppressed by the combination, they have an undoubted privilege to inquire into the preten- sions of both, and equally to reject the usurpation of either. 3 In the following sheets, the author hath studiously avoided everything which is personal among ourselves. Compliments as well as censure to individuals make no part thereof. The wise and the worthy need not the triumph of a pamphlet; and those whose sentiments are injudicious or unfriendly will cease of themselves unless too much pains are bestowed upon their conversion. -

Chapter 5 the Spirit of Independence

Chapter 5 The Spirit of Independence Section 1: Taxation Without Representation Vocab. • Revenue • Resolution • Boycott • Repeal • Effigy • Prohibit • Violate Relations with Britain • Proclamation of 1763 – Prohibited colonists expansion west – Allowed Britain to control trade and commerce in the colonies • British Debt – King and Parliament tax colonists heavily – Strictly enforce tax laws Britain’s Trade Laws • George Grenville – Prime Minister in 1763 – Encouraged laws that allowed smugglers to be tried in vice-admiralty courts (without juries) • Writs of Assistance – 1767: Documents that allowed British officers to enter any location to search for smuggled goods The Sugar Act • Parliament Passes Sugar Act – 1764 – Lowered the tax on imported molasses to convince colonists to pay the tax – Gave officers ability to take smuggled good without going to court • Violated Rights of Colonists – New taxes and trade laws took away rights as English citizens New Taxes • Stamp Act – Passed by Parliament in 1765 – Placed a tax on almost all printed material • Newspapers, wills, playing cards, etc. • Sparked colonial resistance – Colonists opposed being taxed without their consent or approval Protesting the Stamp Act • Patrick Henry – Persuaded the Virginia House of Burgesses to pass a resolution – Declared that only the Virginia Assembly had the authority to tax its citizens • Samuel Adams – Helped start the Sons of Liberty – Protestors burnt effigies and destroyed houses belonging to royal officials Effigy • Rag doll figures that represented British tax collectors Protesting the Stamp Act (cont.) • Boycott – People in colonial cities refused to buy stamps – Refused to buy other European goods also • Nonimportation Agreements – Signed by colonial merchants – Promise not to buy imported goods from Britain The Townshend Acts • Colonists refused to pay internal taxes • Townshend Acts – New taxes only on imported goods from Britain • Glass, tea, paper, etc. -

The American Experiment

The American2 Experiment Assignment government, where majority desires have an even greater impact on the government. This lesson is based on information in the following Although these ideas are associated with the devel- text selections and video. Carefully read and review opment of the U.S. Constitution, they have their roots all of the materials before taking the practice test. in the preceding colonial and revolutionary experi- The key terms, focus points, and practice test are in- ences in America. The colonists’ English heritage had tended to help ensure mastery of the essential politi- stressed the ideas of both limited government and cal issues surrounding the background and creation self-government. To a large extent, the American rev- of the U.S. Constitution. olutionaries were seeking to retain what they had tra- ditionally understood to be their rights as Text: Chapter 2, “Constitutional Democracy: Pro- Englishmen. Controversy between the American col- moting Liberty and Self-Government,” pp. onists and the English developed in the aftermath of 37–48 the French and Indian War, when the British govern- ment sought to impose several new taxes in order to Declaration of Independence, Appendix A raise revenue. The British first enacted the Stamp Act, then the Townshend Act, and then a tax on tea. Video: “The American Experiment” Because they had no representatives in the English Parliament, the colonists were convinced that these taxes violated the principle of “no taxation without Overview representation,” a right recognized by Englishmen. The colonists met together to articulate their griev- Events like the Watergate break-in during the Nixon ances against the British crown at the First Continen- Administration demonstrate that Americans still tal Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. -

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

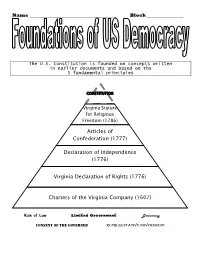

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3.