ASPECTS of ETHICS: Confidentiality, Conflict, and Duty to Your Client

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments Through 2016

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 constituteproject.org Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments through 2016 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 Table of contents CHAPTER I: THE STATE AND THE CONSTITUTION . 7 1. The State . 7 2. Constitution is supreme law . 7 CHAPTER II: PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS OF THE INDIVIDUAL . 7 3. Fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual . 7 4. Protection of right to life . 7 5. Protection of right to personal liberty . 8 6. Protection from slavery and forced labour . 10 7. Protection from inhuman treatment . 11 8. Protection from deprivation of property . 11 9. Protection for privacy of home and other property . 14 10. Provisions to secure protection of law . 15 11. Protection of freedom of conscience . 17 12. Protection of freedom of expression . 17 13. Protection of freedom of assembly and association . 18 14. Protection of freedom to establish schools . 18 15. Protection of freedom of movement . 19 16. Protection from discrimination . 20 17. Enforcement of protective provisions . 21 17A. Payment or retiring allowances to Members . 22 18. Derogations from fundamental rights and freedoms under emergency powers . 22 19. Interpretation and savings . 23 CHAPTER III: CITIZENSHIP . 25 20. Persons who became citizens on 12 March 1968 . 25 21. Persons entitled to be registered as citizens . 25 22. Persons born in Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . 26 23. Persons born outside Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . -

Qatar, France Sign Pact for Strategic Dialogue

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Czech star Pliskova takes tough Vodafone Qatar schedule in posts QR118mn profi t in 2018 her stride published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11092 February 12, 2019 Jumada II 7, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets French FM Amir honours winners of state awards His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani honoured winners of the Qatar’s appreciative and incentive state awards in sciences, arts and literature. His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met with French Minister The award winners were Dr Abdulaziz bin Abdullah Turki al-Subaie in the field of education, Mohamed Jassim al-Khulaifi (museums and archaeology), Dr Saif Saeed of Europe and Foreign Aff airs Jean-Yves Le Drian and his accompanying delegation Saif al-Suwaidi (economics), Dr Yousif Mohamed Yousif al-Obaidan (political science), Dr Hamad Abdulrahman al-Saad al-Kuwari (earth and environmental sciences), at the Amiri Diwan yesterday. The minister conveyed to the Amir the congratulations Mohanna Rashid al-Asiri al-Maadeed (earth and environmental sciences), Dr Huda Mohamed Abdullatif al-Nuaimi (allied medical sciences and nursing), Dr Asma of French President Emmanuel Macron on Qatar national football team winning the Ali Jassim al-Thani (allied medical sciences and nursing), Salman Ibrahim Sulaiman al-Malik (the art of caricature) and Abdulaziz Ibrahim al-Mahmoud in the novel 2019 Asian Cup. During the meeting, they reviewed bilateral relations and means of field. The Amir commended the winners’ distinguished performance, wishing them success in rendering services to the homeland. -

Pupillage: What to Expect

PUPILLAGE: WHAT TO EXPECT WHAT IS IT? Pupillage is the Work-based Learning Component of becoming a barrister. It is a 12- 18 month practical training period which follows completion of the Bar Course. It is akin to an apprenticeship, in which you put into practise everything you have learned in your vocational studies whilst under the supervision of an experienced barrister. Almost all pupillages are found in sets of barristers’ chambers. However, there are a handful of pupillages at the ‘employed bar’, which involves being employed and working as a barrister in-house for a company, firm, charity or public agency, such as the Crown Prosecution Service. STRUCTURE Regardless of where you undertake your pupillage, the training is typically broken down into two (sometimes three) distinct parts or ‘sixes’. First Six First six is the informal name given to the first six months of pupillage. It is often referred to as the non-practising stage as you are not yet practising as a barrister in your own right. The majority of your time in first six will be spent attending court and conferences with your pupil supervisor, who will be an experienced barrister from your chambers. In a busy criminal set, you will be in court almost every day (unlike your peers in commercial chambers). In addition to attending court, you will assist your supervisor with preparation for court which may include conducting legal research and drafting documents such as advices, applications or skeleton arguments (a written document provided to the court in advance of a hearing). During first six you will be required to attend a compulsory advocacy training course with your Inn of Court. -

The Inns of Court and the Impact on the Legal Profession in England

SMU Law Review Volume 4 Issue 4 Article 2 1950 The Inns of Court and the Impact on the Legal Profession in England David Maxwell-Fyfe Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation David Maxwell-Fyfe, The Inns of Court and the Impact on the Legal Profession in England, 4 SW L.J. 391 (1950) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol4/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. 19501 THE INNS OF COURT THE INNS OF COURT AND THE IMPACT ON THE LEGAL PROFESSION IN ENGLAND The Rt. Hon. Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, K.C., M.P., London, England A TTHE present day there are many eminent lawyers who have received a part, perhaps the greater part, of their legal grounding at Oxford or Cambridge or other universities, but there was a time when no legal teaching of any consequence, except in Canon and Roman law, was obtainable anywhere outside the Inns of Court. Sir Wm. Blackstone called them "Our Judicial Univer- sity." In them were taught and trained the barristers and the judges who molded and developed the common law and the principles of equity. The Inns were not in earlier times, as they are now, inhabited merely during the daytime by lawyers and students who dispersed in all directions to their homes every night. -

Women and Legal Rights

Chapter I1 "And Justice I Shall Have": Women and Legal Rights New Brunswickfollowed theEnglishlegal so displacing the legal heritage of the other non-British groups in the province: the aboriginal peoples, the reestablished Acadians and other immigrants of European origin, such as the Germans. Like all law, English common law reflected attitudes towards women which were narrow and riddled with misconceptions and prejudices. As those attitudes slowly changed, so did the law.' Common law evolves in two ways: through case law and through statute law. Case law evolves as judges interpret the law; their written decisions form precedents by which to decide future disputes. Statute law, or acts of legislation, change as lawmakers rewrite legislation, often as a result of a change in public opinion. Judges in turn interpret these new statutes, furthering the evolution of the law. Women's legal rights are therefore much dependent on the attitudes of judges, legislators and society. Since early New Brunswick, legal opinion has reflected women's restricted place in society in general and women's highly restricted place in society when mamed. Single women In New Brunswick, as in the rest of Canada, single women have always enjoyed many of the samelegal rights as men. They could always own and manage property in their own name, enter into contracts and own and operate their own businesses. Their civic rights were limited, although less so at times than for married women. However, in spite of their many legal freedoms not sharedby their married sisters, single women were still subject to society's limited views regarding women's capabilities, potential and place. -

UK Immigration, Legal Aid Funding Reform and Caseworkers

Deborah James and Evan Kilick Ethical dilemmas? UK immigration, Legal Aid funding reform and caseworkers Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: James, Deborah and Killick, Evan (2010) Ethical dilemmas? UK immigration, Legal Aid funding reform and caseworkers. Anthropology today, 26 (1). pp. 13-16. DOI: 10.3366/E0001972009000709 © 2009 Deborah James This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/21396/ Available in LSE Research Online: February 2011 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Ethical dilemmas? UK immigration, legal aid funding reform and case workers Evan Killick and Deborah James Anthropology Today 26(1):13-15. Anthropologists have an abiding concern with migrants’ transnational movement. Such concern confronts us with some sharp ethical dilemmas.1 Anthropologists have been intensely critical of the forms of law applied to both asylum seekers and potential immigrants, drawing attention to its ‘patchy’ and ‘paradoxical’ character (Andersson 2008). -

“Clean Hands” Doctrine

Announcing the “Clean Hands” Doctrine T. Leigh Anenson, J.D., LL.M, Ph.D.* This Article offers an analysis of the “clean hands” doctrine (unclean hands), a defense that traditionally bars the equitable relief otherwise available in litigation. The doctrine spans every conceivable controversy and effectively eliminates rights. A number of state and federal courts no longer restrict unclean hands to equitable remedies or preserve the substantive version of the defense. It has also been assimilated into statutory law. The defense is additionally reproducing and multiplying into more distinctive doctrines, thus magnifying its impact. Despite its approval in the courts, the equitable defense of unclean hands has been largely disregarded or simply disparaged since the last century. Prior research on unclean hands divided the defense into topical areas of the law. Consistent with this approach, the conclusion reached was that it lacked cohesion and shared properties. This study sees things differently. It offers a common language to help avoid compartmentalization along with a unified framework to provide a more precise way of understanding the defense. Advancing an overarching theory and structure of the defense should better clarify not only when the doctrine should be allowed, but also why it may be applied differently in different circumstances. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1829 I. PHILOSOPHY OF EQUITY AND UNCLEAN HANDS ...................... 1837 * Copyright © 2018 T. Leigh Anenson. Professor of Business Law, University of Maryland; Associate Director, Center for the Study of Business Ethics, Regulation, and Crime; Of Counsel, Reminger Co., L.P.A; [email protected]. Thanks to the participants in the Discussion Group on the Law of Equity at the 2017 Southeastern Association of Law Schools Annual Conference, the 2017 International Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference, and the 2018 Pacific Southwest Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference. -

Fat Tony__Co Final D

A SCREENTIME production for the NINE NETWORK Production Notes Des Monaghan, Greg Haddrick Jo Rooney & Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler, Adam Todd, Jeff Truman & Michaeley O’Brien SERIES WRITERS Peter Andrikidis, Andrew Prowse & Karl Zwicky SERIES DIRECTORS MEDIA ENQUIRIES Michelle Stamper: NINE NETWORK T: 61 3 9420 3455 M: 61 (0)413 117 711 E: [email protected] IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTIFICATION TO MEDIA Screentime would like to remind anyone reporting on/reviewing the mini-series entitled FAT TONY & CO. that, given its subject matter, the series is complicated from a legal perspective. Potential legal issues include defamation, contempt of court and witness protection/name suppression. Accordingly there are some matters/questions that you may raise which we shall not be in a position to answer. In any event, please note that it is your responsibility to take into consideration all such legal issues in determining what is appropriate for you/the company who employs you (the “Company”) to publish or broadcast. Table of Contents Synopsis…………………………………………..………..……………………....Page 3 Key Players………….…………..…………………….…….…..……….....Pages 4 to 6 Production Facts…………………..…………………..………................Pages 7 to 8 About Screentime……………..…………………..…….………………………Page 9 Select Production & Cast Interviews……………………….…….…Pages 10 to 42 Key Crew Biographies……………………………………………...….Pages 43 to 51 Principal & Select Supporting Cast List..………………………………...….Page 52 Select Cast Biographies…………………………………………….....Pages 53 to 69 Episode Synopses………………………….………………….………..Pages 70 to 72 © 2013 Screentime Pty Ltd and Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd 2 SYNOPSIS FAT TONY & CO., the brand-new production from Screentime, tells the story of Australia’s most successful drug baron, from the day he quit cooking pizza in favour of cooking drugs, to the heyday of his $140 million dollar drug empire, all the way through to his arrest in an Athens café and his whopping 22-year sentence in Victoria’s maximum security prison. -

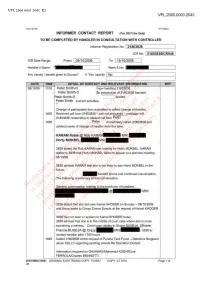

Redactions Have Been Applied by the Royal Commission in This Document

VPL.2000.0003.2043_R2 VPL.2000.0003.2043 New 07/05 VP1092A INFORMER CONTACT REPORT (For DSU Use Only) TO BE COMPLETED BY HANDLER IN CONSULTATION WITH CONTROLLER Informer Registration No: | 21803838 | ICR No: I 21803838ICR048 | ICR Date Range From: | 09/10/2006 | To: I 15/10/2006 | Handler’s Name: Rank & No: Any money! benefit given to Source? If ‘Yes’ specify No DATE TIME DETAIL OF CONTACT AND RELEVANT INFORMATION REF 09/10/06 1315 Peter Smith-0 | now handling 21803838. Peter Smith-0 |in possession ofCommission 21803838 handset. Peter Smith-0 _ _ _______ briefed Peter Smith Current activities. it including, Royal Change of participants form submitted to reflect changelegal of handler. 1405 Received call from 21803838 -the call not answered - message left. 21803838 responding to missed call from Peter 1405 byPeter reasonsimmediately called 21803838 and advised same of change of handler from this time. determined of immunity,non-publication KARAM Rabie @ Rob KARAM^^^Mof has legislative, Horty MOKBEL^^Happlied mNI^^^H numberinterest 3838 beenstated the a Rob KARAM was looking for Horty MOKBEL. KARAM stated to 3838 that Horty MOKBEL failed to appear at a planned meeting 08/10/06.for operation have public Commissionreputational, 3838 advisedto, KARAM that she is not likely to see Horty MOKBEL in the future. ________the on privilege, handed phone and continued conversation. documentThe following a summary of that conversation. limited wherebased reasons. Redactionsthis General conversation relating to the handover of handlers. not in and @ M N1: but safety professional3838 stated thator she last saw Kamel KHODER on Sunday - 08/10/2006 orders,andappropriate drove same to Crispy Creme Donuts at the request of Kamel KHODER. -

Final Report IV

Final Report Volume IV VOLUME IV NOVEMBER 2020 Royal Commission into the Management of Police Informants Final Report Volume IV The Honourable Margaret McMurdo, AC Commissioner ORDERED TO BE PUBLISHED Victorian Government Printer November 2020 PP No. 175, Session 2018–2020 Final Report: Volume IV 978-0-6485592-4-5 Published November 2020 ISBN: Volume I 978-0-6485592-1-4 Volume II 978-0-6485592-2-1 Volume III 978-0-6485592-3-8 Volume IV 978-0-6485592-4-5 Summary and Recommendations 978-0-6485592-5-2 Suggested citation: Royal Commission into the Management of Police Informants (Final Report, November 2020). Contents Chapter 14: The use and disclosure of information from human sources in the criminal justice system 4 Chapter 15: Legal profession regulation 66 Chapter 16: Issues arising during the conduct of the Commission’s inquiry 120 Chapter 17: Work beyond the Commission 152 14 The use and disclosure of information from human sources in the criminal justice system INTRODUCTION Term of reference 4 required the Royal Commission to inquire into and report on the current use of information in the criminal justice system from human sources who are subject to legal obligations of confidentiality or privilege. Term of reference 4 also directed the Commission to examine a very specific aspect of disclosure in criminal cases; namely, the appropriateness of Victoria Police’s practices for the disclosure or non-disclosure of the use of such human sources to prosecuting authorities. Term of reference 5b required the Commission to consider measures that may be necessary to address any systemic or other failures arising from the use of information obtained from human sources subject to legal obligations of confidentiality or privilege in the criminal justice system, and how such failures may be avoided in the future. -

Com.0104.0001.0001 R1 P Com.0104.0001.0001 R1 Com.0104.0001,0001 0001

COM.0104.0001.0001_R1_P COM.0104.0001.0001_R1 COM.0104.0001,0001_0001 I, SHARON ELIZABETH CURE of|_____ in the State of Tasmania DO SOLEMNLY and SINCERELY DECLARE THAT: 1. I have been a Magistrate in the State of Tasmania since 12 January 2015. 2 . I signed the Victorian Bar roll in March 2000 and practised as a barrister until I was appointed a Magistrate in Victoria in 2008.1 had previously been a solicitor with the Office of Public Prosecutions for 9 years. 3. In response to the requestfor information dated 8 February 2020 I make this statement addressing the specific topics contained in that request. 4. In 1999 I came to know Nicola Gobbo when I was prosecuting a prostitution control matter. She was defence counsel. I was concerned about her conduct in that matter. 5. Nothing subsequent changed my concern abouther. 6. I moved to Crockett Chambers in early 2005. 7. In 2006 Nicola Gobbo took over the room when a member of chambers went overseas. It was supposed to be a temporary arrangement enabled by Mr Heliotis QC. 8. In June of 2007 I occupied a room on the 7th floor. Later that year I moved to the 6th floor. 9. I believe I always locked my chambers. I was sharing with another barrister in some of 2007. I cannot exclude the possibility that the door was left unlocked. 10. A master key to all the rooms on the 7th floor was kept in the power box cupboard in the small hallway to the kitchen. That was well known and if access was needed to any chambers it was available to anyone. -

Informer 3838: a Web of Deceit ! Admin " 1 Week Ago # Latest News $ 29 Views

Informer 3838: A web of deceit ! admin " 1 week ago # Latest News $ 29 Views One of the officers treated the protection duty like an end-of-season football trip, getting so drunk that she had to help him back to his hotel. Another was a fish out of water on his first overseas jaunt, his discomfort aggravated by a paranoia about germs. Kuta Beach in Bali, where police officers took Informer 3838.Credit:Alamy Meanwhile, back in Melbourne’s underworld, the case itself was being undermined. Gangland killer Carl Williams was the star witness, but the lawyer was the police’s ace up the sleeve. Her involvement was to be kept under wraps for as long as possible. A detective later told the court that three people in Barwon Prison maximum security already knew the lawyer was a witness in the upcoming committal hearing. “It’s fanciful to think the word hasn’t spread,” another lawyer said at the time. Then, in the wake of a breakdown in her relationship with police and their attempts to protect her identity, Informer 3838 did an extraordinary handbrake turn and sued them for failing in their duty to keep her safe. In her decade-long career as a barrister, Informer 3838 had represented a who’s who of Melbourne’s underworld. She had become a trusted adviser to drug traffickers, murderers and mafia figures. Former drug squad detective Paul Dale at Melbourne Magistrates Court in 2010 for proceedings over the murder of police informer Terence Hodson.Credit:Craig Abraham When she reluctantly agreed to become a witness against Dale for the Hodson murders, both police and the lawyer believed the criminal fraternity would not care that she was co-operating to punish an allegedly bent cop.