Informer 3838: a Web of Deceit ! Admin " 1 Week Ago # Latest News $ 29 Views

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript of Proceedings

IBAC.0007.0001.0014_R1 IBAC.0007.0001.0014_0001 TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS OFFICE OF POLICE INTEGRITY MR G.E. FITZGERALD AC QC MR G.H. LIVERMORE MR G. CARROLL HEARING PURSUANT TO SECTION 86P(1)(a) OF THE POLICE REGULATION ACT 1958 EXAMINATION OF NICOLA GOBBO MELBOURNE 11.21 AM, THURSDAY, 19 JULY 2007 PROCEEDINGS RECORDED BY THE OFFICE OF POLICE INTEGRITY VICTORIA .Gobbo 19.7.07 13.] Transcript—innConfidence IBAC.0007.0001.0014_0002 MR FITZGERALD: - - - to go through, which we'll do as quickly as we can. By the way, I'm Tony Fitzgerald, if you haven‘t been told, and I'll read my technically correct name onto to the record in just a moment. Please commence recording, if it has not commenced. Today's date is 19 July 2007 and the time is approximately 25 past 11 in the morning. My name is Gerald Edward Fitzgerald and the director of police integrity has by instrument delegated the powers necessary to conduct this hearing. I have a - produce a true copy of an instrument of delegation which will be exhibit 1. EXHIBIT #1 - INSTRUMENT OF DELEGATION MR FITZGERALD: Pursuant to my delegated powers, thank you, I authorise the following persons to be present in this hearing: the witness Ms Nicola Gobbo, Mr Garry Livermore of counsel, Mr Greg Carroll of the Office of Police Integrity. EXHIBIT #2 - ORDER AUTHORISING PERSONS TO BE PRESENT MR FITZGERALD: With the exception of those whose presence I have just authorised I am satisfied that the exclusion of the public from these proceedings would facilitate the conduct of the investigation to which this hearing relates and would be in the public interest. -

Qatar, France Sign Pact for Strategic Dialogue

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Czech star Pliskova takes tough Vodafone Qatar schedule in posts QR118mn profi t in 2018 her stride published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11092 February 12, 2019 Jumada II 7, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets French FM Amir honours winners of state awards His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani honoured winners of the Qatar’s appreciative and incentive state awards in sciences, arts and literature. His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met with French Minister The award winners were Dr Abdulaziz bin Abdullah Turki al-Subaie in the field of education, Mohamed Jassim al-Khulaifi (museums and archaeology), Dr Saif Saeed of Europe and Foreign Aff airs Jean-Yves Le Drian and his accompanying delegation Saif al-Suwaidi (economics), Dr Yousif Mohamed Yousif al-Obaidan (political science), Dr Hamad Abdulrahman al-Saad al-Kuwari (earth and environmental sciences), at the Amiri Diwan yesterday. The minister conveyed to the Amir the congratulations Mohanna Rashid al-Asiri al-Maadeed (earth and environmental sciences), Dr Huda Mohamed Abdullatif al-Nuaimi (allied medical sciences and nursing), Dr Asma of French President Emmanuel Macron on Qatar national football team winning the Ali Jassim al-Thani (allied medical sciences and nursing), Salman Ibrahim Sulaiman al-Malik (the art of caricature) and Abdulaziz Ibrahim al-Mahmoud in the novel 2019 Asian Cup. During the meeting, they reviewed bilateral relations and means of field. The Amir commended the winners’ distinguished performance, wishing them success in rendering services to the homeland. -

Fat Tony__Co Final D

A SCREENTIME production for the NINE NETWORK Production Notes Des Monaghan, Greg Haddrick Jo Rooney & Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler, Adam Todd, Jeff Truman & Michaeley O’Brien SERIES WRITERS Peter Andrikidis, Andrew Prowse & Karl Zwicky SERIES DIRECTORS MEDIA ENQUIRIES Michelle Stamper: NINE NETWORK T: 61 3 9420 3455 M: 61 (0)413 117 711 E: [email protected] IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTIFICATION TO MEDIA Screentime would like to remind anyone reporting on/reviewing the mini-series entitled FAT TONY & CO. that, given its subject matter, the series is complicated from a legal perspective. Potential legal issues include defamation, contempt of court and witness protection/name suppression. Accordingly there are some matters/questions that you may raise which we shall not be in a position to answer. In any event, please note that it is your responsibility to take into consideration all such legal issues in determining what is appropriate for you/the company who employs you (the “Company”) to publish or broadcast. Table of Contents Synopsis…………………………………………..………..……………………....Page 3 Key Players………….…………..…………………….…….…..……….....Pages 4 to 6 Production Facts…………………..…………………..………................Pages 7 to 8 About Screentime……………..…………………..…….………………………Page 9 Select Production & Cast Interviews……………………….…….…Pages 10 to 42 Key Crew Biographies……………………………………………...….Pages 43 to 51 Principal & Select Supporting Cast List..………………………………...….Page 52 Select Cast Biographies…………………………………………….....Pages 53 to 69 Episode Synopses………………………….………………….………..Pages 70 to 72 © 2013 Screentime Pty Ltd and Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd 2 SYNOPSIS FAT TONY & CO., the brand-new production from Screentime, tells the story of Australia’s most successful drug baron, from the day he quit cooking pizza in favour of cooking drugs, to the heyday of his $140 million dollar drug empire, all the way through to his arrest in an Athens café and his whopping 22-year sentence in Victoria’s maximum security prison. -

PDF Download Gangland Melbourne Ebook, Epub

GANGLAND MELBOURNE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Morton | 208 pages | 01 Oct 2011 | Melbourne University Press | 9780522858693 | English | Carlton, Australia Gangland Melbourne PDF Book EU leaders to discuss plans to roll-out Covid vaccine passports - while Britons who have received jabs will Ordinary Australians are being fined extortionate amounts for doing regular things like exercising outside for too long. News Home. Medical emergency involving flight crew member forces Virgin plane to return to Adelaide Posted 5 h hours ago Fri Friday 15 Jan January at am. Scottish Tories suspend candidate who claimed 'fat' foodbank users are 'far from starving' and accused Rebel Roundup Every Friday. The world's most popular perfume revealed: Carolina Herrerra's Good Girl is the most in demand across the Many of the murders remain unsolved, although detectives from the Purana Taskforce believe that Carl Williams was responsible for at least 10 of them. In the wake of the Informer scandal, Williams believed she could still get back the Primrose Street property, which was seized to repay her family's tax debt. May 8, - Lewis Caine, a convicted killer who had changed his name to Sean Vincent, shot dead and his body dumped in a back street in Brunswick. Never-before-seen photos of the St Kilda murder scene of an underworld figure have been released as part of a renewed police push for answers over the major event in the early years of Melbourne's gangland war. It is not allowed to happen,' she said. Boris Johnson and the Two Ronnies could be replaced by An edited version commenced screening in Victoria on 14 September Investigation concludes Joe the pigeon had a fake US leg band and won't be executed. -

HER HONOUR: > You Have Pleaded Guilty to the .Murder of Jason Moran

COR.1000.0004.0001_ER2_P HER HONOUR: i Mr Thomas i 1 1 ’ > you have pleaded guilty to the .murder of Jason Moran which occurred on 21 June 2003 in the Cross Keys Reserve in Pascoe Vale. The Crown position as stated by the Senior Crown Prosecutor, Mr Horgan SC, in respect of your plea is as follows: that Jason Moran and Pasquale Barbaro were shot dead in the carpark at the Cross Keys Reserve in Pascoe Vale on that date. They were in a van about to drive 1.0 children home from the Auskick football clinic, including the children of Jason Moran, The children were in thfe rear of i Mr McGrath ! the van. Mr Andrews had been driven to the reserve area byL-------- ! i Mr McGrath I I___________________ J who dropped him off near the van and drove off, approached the van and, using a shotgun, fired through the window of the van. He then dropped that weapon and used a hand gun pointed through the driver’s side window, aiming at the head of Jason Moran. Both Jason Moran, who was seated in the driver's side, and Pasquale Barbaro, who was in the passenger seat of the vehicle, were killed, 2 The Crown accepted for the purposes of your plea that the target for your attack was Jason Moran. Pasquale Barbaro was an unintended victim who was, as the prosecutor stated, "In the wrong place at the wrong time". 34 3 The background to this killing was the enmity between Carl Williams and the Morans, over the Morans' shooting of Williams in the stomach some years earlier. -

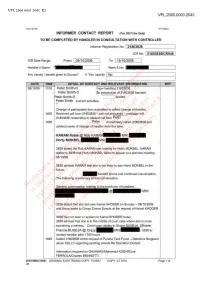

Redactions Have Been Applied by the Royal Commission in This Document

VPL.2000.0003.2043_R2 VPL.2000.0003.2043 New 07/05 VP1092A INFORMER CONTACT REPORT (For DSU Use Only) TO BE COMPLETED BY HANDLER IN CONSULTATION WITH CONTROLLER Informer Registration No: | 21803838 | ICR No: I 21803838ICR048 | ICR Date Range From: | 09/10/2006 | To: I 15/10/2006 | Handler’s Name: Rank & No: Any money! benefit given to Source? If ‘Yes’ specify No DATE TIME DETAIL OF CONTACT AND RELEVANT INFORMATION REF 09/10/06 1315 Peter Smith-0 | now handling 21803838. Peter Smith-0 |in possession ofCommission 21803838 handset. Peter Smith-0 _ _ _______ briefed Peter Smith Current activities. it including, Royal Change of participants form submitted to reflect changelegal of handler. 1405 Received call from 21803838 -the call not answered - message left. 21803838 responding to missed call from Peter 1405 byPeter reasonsimmediately called 21803838 and advised same of change of handler from this time. determined of immunity,non-publication KARAM Rabie @ Rob KARAM^^^Mof has legislative, Horty MOKBEL^^Happlied mNI^^^H numberinterest 3838 beenstated the a Rob KARAM was looking for Horty MOKBEL. KARAM stated to 3838 that Horty MOKBEL failed to appear at a planned meeting 08/10/06.for operation have public Commissionreputational, 3838 advisedto, KARAM that she is not likely to see Horty MOKBEL in the future. ________the on privilege, handed phone and continued conversation. documentThe following a summary of that conversation. limited wherebased reasons. Redactionsthis General conversation relating to the handover of handlers. not in and @ M N1: but safety professional3838 stated thator she last saw Kamel KHODER on Sunday - 08/10/2006 orders,andappropriate drove same to Crispy Creme Donuts at the request of Kamel KHODER. -

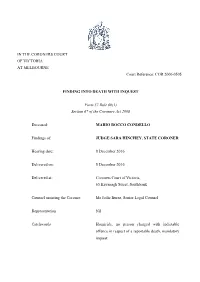

COR 2006 0505 FINDING INTO DEATH with INQUEST Form 37

IN THE CORONERS COURT OF VICTORIA AT MELBOURNE Court Reference: COR 2006 0505 FINDING INTO DEATH WITH INQUEST Form 37 Rule 60(1) Section 67 of the Coroners Act 2008 Deceased: MARIO ROCCO CONDELLO Findings of: JUDGE SARA HINCHEY, STATE CORONER Hearing date: 8 December 2016 Delivered on: 8 December 2016 Delivered at: Coroners Court of Victoria, 65 Kavanagh Street, Southbank Counsel assisting the Coroner: Ms Jodie Burns, Senior Legal Counsel Representation Nil Catchwords Homicide, no person charged with indictable offence in respect of a reportable death, mandatory inquest TABLE OF CONTENTS Background 1 The purpose of a coronial investigation 2 Victoria Police homicide investigation 3 Matters in relation to which a finding must, if possible, be made - Identity of the deceased 5 - Medical cause of death 5 - Circumstances in which the death occurred 6 Findings and conclusion 8 HER HONOUR: BACKGROUND 1 Mario Rocco Condello (Mr Condello) was born on 12 April 1952 at the Royal Women’s Hospital, Carlton to . Mr Condello had an older sister, , and a younger brother, . Mr Condello’s parents, who were originally from Italy, taught him to speak Calabrese, the primary language of the Southern Italian region of Calabria. 2 After leaving High School, Mr Condello commenced a law degree at Monash University, from which he graduated in 1976. In his final year of university Mr Condello met and commenced a relationship with and they married in 1978. 3 Also in 1978, Mr Condello commenced his own legal practice, ‘Mario Condello Solicitors’, in Best Street, North Fitzroy. During this period of time, North Fitzroy had a prominent Italian community and as a result, Mr Condello gained a number of Italian clients. -

New York City Council Bans N-Word

INTERNATIONAL CHINA DAILY FRIDAY MARCH 2, 20079 WORLDSCENE New York city council bans N-word UNITED STATES councillor who proposed the reso- ment right to free speech, Richards come to be seen by many as the most ‘Old Man’ of mafi a’s guilty plea Black screenwriters and rappers urged lution, has called on the academy said, pointing to the supreme court’s offensive racial slur in English. A 96-year-old gangster who oversaw which runs the Grammy awards decision to uphold the right to burn Roy Miller, a lawyer from Atlanta, robberies, money laundering, bank to rein back use of racist term following to withhold nominations from acts the American fl ag, and its ruling that Georgia, was invited to speak to a fraud and other crimes for one of using it. At the awards last month, a man resisting military conscription committee of the New York council the largest mafi a families in the councillors unanimous vote for crackdown artists such as Ludacris and Chamil- had the right to wear a jacket in court when it debated the resolution on US pleaded guilty yesterday, but lionaire were honored for songs which saying “fuck the draft”. Monday. The civil rights committee because of his age will probably be ew York banned the word mon use of the word, especially in contained the term. Marcia Williams, of the campaign- voted by fi ve to none to pass the reso- sentenced to house arrest. nigger yesterday in a the black community, where it has ing website Ban the N-word, said that lution imposing a moratorium. -

Justice Betty �Ing: a Study of Feminist Judging in Action

UNSW Law Journal Volume 40(2) 13 JUSTICE BETTY ING: A STUDY OF FEMINIST JUDGING IN ACTION ROSEMARY HUNTER AND DANIELLE TYSON I INTRODUCTION Justice Betty King sat on the Supreme Court of Victoria for 10 years from 2005–15. Prior to that she was a judge of the Victorian County Court from 2000– 05 after a career at the Victorian Bar from 1975–2000. During her career she was a pioneer for women in many respects, being only the 24th woman called to the Victorian Bar, the first woman prosecutor in Victoria, the first woman Commonwealth prosecutor, and one of the first Victorian women appointed a C. 1 As a Supreme Court judge, Justice King was known for ‘speaking her mind’, her ‘no nonsense approach and colourful attire’.2 She gained a high profile in her role in the series of trials associated with the Melbourne gangland killings dramatised in the television series, Underbelly.3 She was the judge who banned the broadcast of Underbelly in Victoria during the murder trial of one of its protagonists, Carl Williams, 4 and she also banned a Today Tonight episode featuring a showdown between Carl Williams’ mother and the mother of Lewis Moran during the trial of Evangelos Goussis for Moran’s murder.5 In a May 2010 interview she spoke out against the media’s treatment of prominent defendants Professor of Law and Socio-Legal Studies, ueen Mary University of London. Senior Lecturer in Criminology, Deakin University. 1 Li Porter, ‘King of Her Court’, The Age (online), 18 November 2007 <http://www.theage.com.au/news/ in-depth/king-of-her-court/2007/11/17/1194767017489.html>; Stefanie Garber, ‘High-Profile Judge Betty King Retires’, Lawyers Weekly (online), 17 August 2015 <http://www.lawyersweekly.com.au/wig- chamber/16981-high-profile-judge-betty-king-retires>. -

Sue Barnett & Associates

sue barnett & associates GYTON GRANTLEY TRAINING 2001 BA (Drama), QUT Academy of the Arts FILM 2016 The Anthesis of Man (Short) Vic Lauren Ford/Vicki Gest Dir: Dan Macarthur Don’t Tell Kevin Guy Tojohage Productions/ Scott Corfield Productions Dir: Toro Garrett 2015 We Were Tomorrow Cain WWT Motion Picture Pty Ltd / Mad Lane Productions Dir: Darwin Brooks Spaghetti (Short) Principal B. R. Occoli Peter Nizic 2014 The Dressmaker Barney McSwiney Film Art Media Dir: Jocelyn Moorehouse 2011 Rarer Monsters (Short) Terry Rarer Monsters Pty Ltd Utopia (Short) Director Spirited Films The Forgotten Men (Short) Wood Carver Campfire Pictures Pty Ltd Dir: Jack Wareham 2010 Maestro (Short) Maestro Dir: Adam Anthony Everything’s Super (Short) Shadow Chaotic Pictures Dir: Gareth Davies Full Catch (Short) Ramon Dir: Meghan Carlsen Lucydia (Short) James AFTRS Dir: Jonny Peters 2009 The Reef Matt Prodigy Movies Pty Ltd Dir: Andrew Traucki Beneath Hill 60 Norm Morris The Silence Productions Dir: Jeremy Simms Being Carl Williams (short) Himself Dir: Abe Forsythe 2008 Beyond Words (Short) Ben Dir: Armand De Saint-Salvy Balibo Gary Cunningham Balibo Film Pty Ltd Dir: Robert Connelly Prime Mover Repo Man Porchlight Films Dir: David Caesar 2006 All My Friends Are Jake AFC Leaving Brisbane Dir: Louise Alston 2005 Black Fury (Short) Roy Catherine Millar 2003 A Man’s Gotta Do Dominic Dir: Chris Kennedy Under The Radar Trent Dir: Evan Clarry 2002 Danny Deck Chair Stuey Dir: Jeff Balsmeyer Blurred Gavin Pictures in Paradise Dir: Even Clarry 2001 Swimming Upstream -

Contents 28Th DECEMBER 1986

THIS DOCUMENT IS COPY RIGHT OF C.D.P FOR VIEWING PURPOSES ONLY. TO SHARE, TO AND PROMOTE ITS VALUABLE CONTENT TO CAGED UNTOLD.ALL. ALL RIGHTS ARE RESERVED BY C.D.P ABSORB! Contents Frank Waghorn. A.K.A. “Laghorn.” ....................................................................................................... 1 COPPER WITH THE SILENT “H”. ............................................................................................................. 2 Craig “SLIM” with an E. Minogue. .......................................................................................................... 2 Chopper was the worst snitch of all ...................................................................................................... 3 SUPER SNITCH “Keith Faure” ................................................................................................................ 3 Nick Levidis, and Chris Stone ................................................................................................................ 3 The Christmas card From Frank & Chopper. .......................................................................................... 4 PETER GIBB: ........................................................................................................................................... 5 LEWIS CAINE: ......................................................................................................................................... 6 J. Malcoun. ............................................................................................................................................ -

Submission Victorian Royal Commission: the Management Of

SUB.0067.0001.0001 0001 SUB.0067.0001.0001 R1 This document has been redacted for Public Interest Immunity claims made by Victoria Police. These claims are not yet resolved. Submission Victorian Royal Commission: The Management of Police Informants W. H. Robertson March, 2019 1 SUB.0067.0001.0001 0002 This document has been redacted for Public Interest Immunity claims made by Victoria Police. These claims are not yet resolved. Contents Abbreviations 3 Synopsis 4 About the Author 5 Introduction 6 TOR 1 6 Context 6 TOR 2 7 Witness protection — human sources 7 TOR 3 8 Kellam Report 8 Legal professional privilege 8 Other places 10 TOR 4 12 Can LPP be breached? 13 George Dean 14 TOR 5 15 A way forward? 15 Qualified privilege for the purpose of 21 Criminal investigation FOR 6 22 Conclusion 24 End Notes 26 Attachment 1 “Gangland warfare” context Attachment 2 Upgrading detective training 1 SUB.0067.0001.0001 0003 This document has been redacted for Public Interest Immunity claims made by Victoria Police. These claims are not yet resolved. Abbreviations ALRC Australian Law Reform Commission CDPP Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions DPP Director of Public Prosecutions lAP International Association of Prosecutors IBAC Independent Broad-based Anticorruption Commission LPP Legal professional privilege OPI Office of Police Integrity SOCA Serious Organised Crime Agency SOI School of Investigation TOR Terms of Reference VGSO Victorian Government Solicitor's Office Witsec Victoria Police Witness Protection Program 3 SUB.0067.0001.0001 0004 This document has been redacted for Public Interest Immunity claims made by Victoria Police.